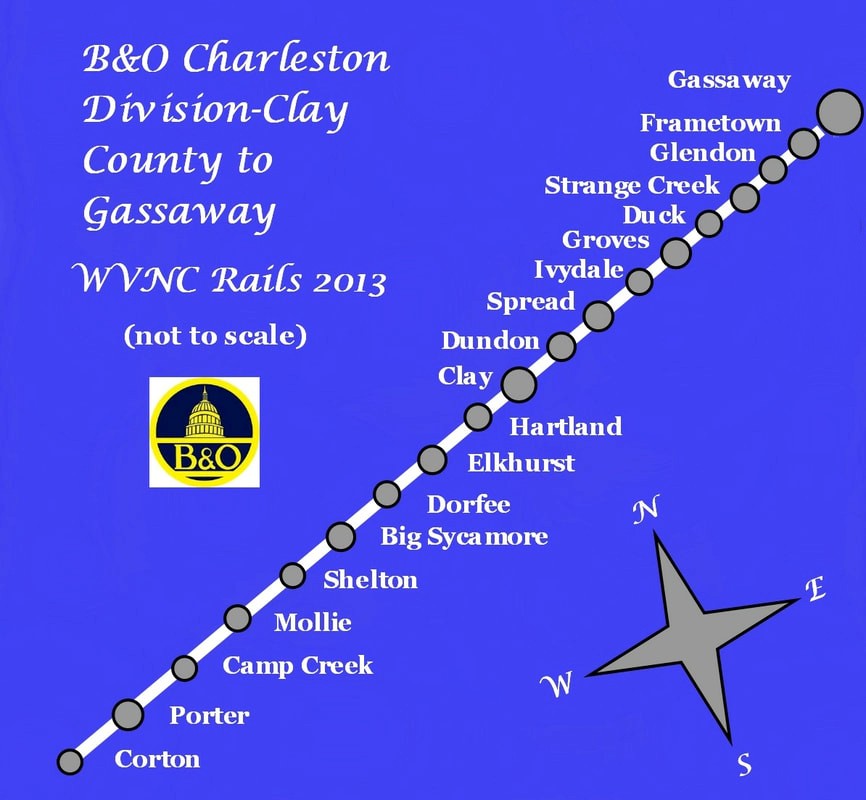

B&O Charleston Division Part II-Clay County to Gassaway

From a personal standpoint, I seldom saw this region when the railroad was active as a through route and have few firsthand accounts to share here. As an added consequence, historical records are sparse as are photographs. Images of the past will be added as they are obtained along with contemporary of my own as well as contributors recording the remnants of recent years.

The B&O in this region proved to be a paradox in regards to a railroad traversing rugged but beautiful country following the crooked course of the Elk River bend for bend. This scenic remoteness also rendered this stretch of railroad vulnerable due to few on line rail customers and especially so in the latter years. In bygone years when the B&O ran scheduled freights and operated passenger trains between Grafton, Gassaway, and Charleston, the line was a valuable north-south link through the heart of West Virginia. By the end of the 1970s, all that remained were a few shippers scattered along the route with none remaining between Clay to just below Clendenin. This resulted in a thirty mile section of railroad that B&O (Chessie System) deemed costly to maintain and therefore became expendable. Since the remaining customers west of Clendenin could be serviced by the C&O from Charleston, the decision was made to sever the line and the track was removed between Hartland and Reamer in 1981. Six years later in 1987, the B&O (Chessie System) itself ceased to exist as it was among several roads that would vanish into CSX. Shortly after the formation of CSX, the former B&O from Gilmer through Gassaway to Hartland was sold and reborn as the Elk River Railroad (TERRI) of which it remains today.

Hope springs eternal and during the mid 1990s, a phoenix almost rose from the ashes of a vanished rail line when TERRI announced a proposal to rebuild the railroad from Hartland to Falling Rock to secure a western outlet at Charleston. This was based on the discovery of additional mineable coal reserves in Clay County that would justify the rebuild. Unfortunately, the mining did not develop and this glimmer of hope faded which effectively ended any ideas of a railroad renaissance. Today, the song remains the same.

Timing is everything. Thirty years hence, it obviously would have been easier to undertake this project when the railroad still existed in the region. If not, then unquestionably within a few years of the track abandonment when other related trackside features were still intact. Although much is unchanged in the Elk Valley within this time frame, the former right of way has been converted to vehicle use at various locations thereby forever altering the integrity of the former roadbed. In addition, there has been property modifications that have wrought forth changes. With this in mind and to the best of my resources, presented will be reflections of the past interspersed with views as they are today both with the pen and lens.

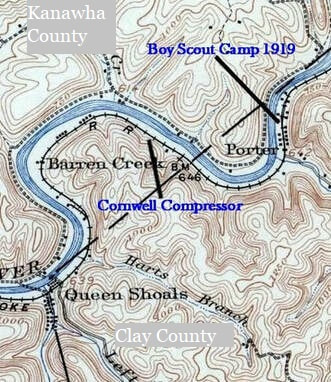

Kanawha-Clay County Line

|

It is in this area east of Queen Shoals where the Elk River begins a crooked stretch of bends that extends for miles. The river and railroad straddle the Kanawha and Clay County line entering and exiting both counties with each bend in the river.

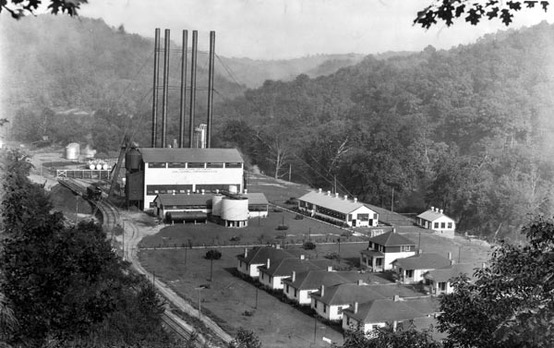

Prominent in this section is the Cornwell Gas Compressor and the community of Porter located at the mouth of the creek by the same name. The compressor station is actually listed as being located at Corton which is the place name on both sides of the river. |

The topography of the Elk River valley undergoes a gradual transformation moving east from Queen Shoals. The hills increase in elevation, the valley narrows, and the river passes through numerous eddies and shoals. It is an area of few residences and begins the section of the Elk Valley that was and is prime territory for summer camps and retreats.

|

The Cornwell Compressor Station and its relationship to the railroad as it appeared circa 1930. The community of Corton was mainly comprised of employees that worked at the station. The compressor is still in operation but only a few homes remain in this small Elk River hamlet today. Photo courtesy Mack Samples/Dominion Resources

|

A view at the west end of the Cornwell gas compressor station as it appears today. B&O trains passed by here for many years as the visible right of way is in evidence. Image by Earl Fridley

|

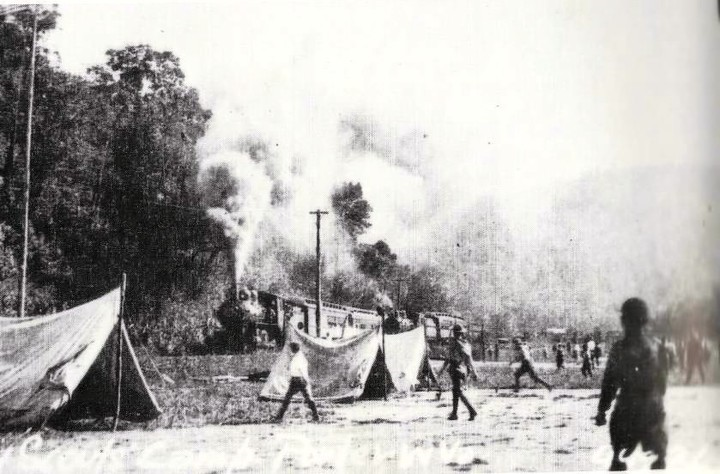

Porter was the quintessential small community along the Elk River and was representative of uncounted similar place locations that once lined the railroads of America. At the onset of the 20th century, Porter included a general store and post office in addition to existing as a whistle stop for the residents along the river here and the creek by the same name. There once was a small railroad called the Porter Creek and Gauley that operated along the creek to tap into the abundant timber industry that once thrived in the vicinity. But this line must have vanished by the turn of the century since it is absent from the 1906 topographical map used herein. In conjunction with this small line was a bandsaw mill that was located near the mouth of Porter Creek. This line connected with what would become the B&O in later years at the namesake town of Porter. During the early years of the Boy Scouts, a summer camp was located here and they would travel to the area by train. The depot at Porter (B&O call letters OR) remained active until about 1950 when it was closed.

|

The young boy in this scene has been frozen in time for nearly a century as he gazes at the activity ahead. This 1919 image is most unique because it captured the Boy Scouts in its infancy and two trains at the same location. The train to the left is eastbound headed for Clay and beyond as it passes the troop train in the siding at Porter. (Image courtesy Buckskin Boys: A History of the Buckskin Council of the Boy Scouts of America, 1910-2004, W. Joseph Wyatt, author, Pictorial Histories, publisher.)

|

|

The railroad crossing of Porter Creek was the longest bridge on the railroad between Charleston and Gassaway. Not only did it span the creek but a road also as seen at right. Piers are all that remain of a location that once echoed with the sound of passing trains. Image courtesy Jeanie Droddy/ Herb Wheeler collection

|

A passing siding was located at Porter for train meets and undoubtedly was utilized for loads of timber coming off the PC & G when the line was active. This siding remained until the final years of the B&O although by this time train meets were long a thing of the past. It functioned as storage track for any shipments to the Cornwell Gas Compressor or to set out a bad order car.

|

Trains once passed above here as they crossed Porter Creek. The thick canopy of trees shield the sun even on the brightest of days. Dan Robie 2018

|

Grassy railroad roadbed looking west at Porter. The growth flanking each side of the right of way has proliferated since the track was removed in 1981. Dan Robie 2018

|

In an unrelated but noteworthy vein, Porter Creek holds a significant spot in the annals of horticulture. It was along this creek that the renowned Golden Delicious apple was discovered in 1905.

Bends of the Elk

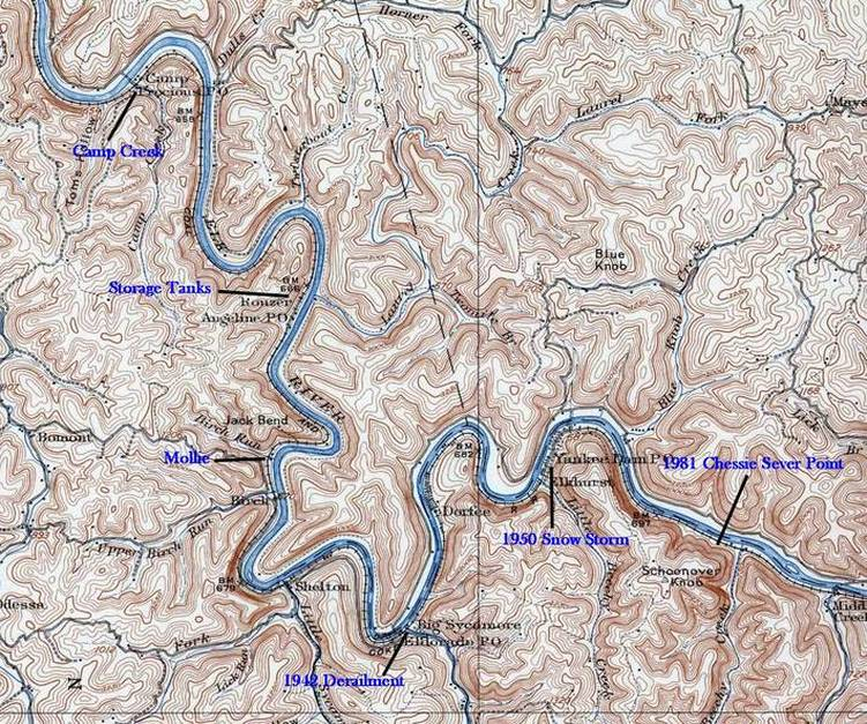

With a profile resembling a snake the Elk River twists and turns through the Clay County landscape draining small creeks and passing by small communities obscured by time. Easily the most remote section of territory that B&O traversed between Charleston and Gassaway, it is also the most inaccessible and mysterious. The railroad is gone but the scenic beauty in which it ran remains. This 1907 topo map of the region is a jewel because it recalls place names that are now largely forgotten.

Thoughts of noted author W.E.R Byrne’s descriptions freely come to mind upon thinking about the area between Queen Shoals and Hartland. His book, Tale of the Elk, is a compilation of short stories written during the 1920s of the early 20th century Elk Valley of which he so adored. His short stories recollect a long gone era of the families and life style of those who resided in the valley and the zeal for life and the outdoors is expressed most eloquently. Mr. Byrne was a distinguished Charleston lawyer but from reading the anecdotes in his book, it was fishing and the associations he had with so many along the banks of the Elk that gave him the greatest fulfillment.

So much of the Elk River valley that existed during Mr. Byrne’s lifetime has remained intact and it is quite easy for one to visit these remote yet picturesque settings and understand the impressions cast on him so many years ago. The Elk, quite simply, is a magnificent stream defined by the placidity of its pools and the rapidity of its shoals. The region from east of Queen Shoals to Hartland, referred to as the Bends of the Elk in this chapter, is the embodiment of this state as the river twists around bends within a narrow valley.

There was little on line traffic generated for the B&O and its predecessors in this section even during the early 1900s excepting for small coal operators. Most notable was the Middle Creek Railroad that connected with the B&O at Hartland and followed the namesake creek to Bickmore serving coal mines along the route. This five mile short line railroad remained active until 1951. There was also a logging line, Porter Creek and Gauley, which followed the watershed of the creek and joined the railroad at Porter. This small line had vanished by the early 1900s.

Curious place names dotted the railroad along this stretch and among them were flag whistle stops such as Porter, Camp Procious, Rouzer, Shelton, Dorfee, Yankee Dam, Elkhurst, and Hartland. Population was (and still is) sparse with few residences and camps scattered along the line. Although no industries other than coal mines were located adjacent to this winding stretch of track, the railroad did manage to install passing sidings on the brief tangents to accommodate meets which was paramount in the halcyon years when passenger trains graced the route. There were no less than five of these passing sidings—Porter, Rouzer, Shelton, Dorfee, and Elkhurst. By the 1970s, only the one at Porter remained. Due to the topography the railroad traversed with the ever twisting curves, maximum speed was 25 MPH and in the twilight years of operation, that limit was reduced to 10 MPH owing to lesser maintenance.

Although a scenic vista, this section of railroad in the Bends of the Elk region was a maintenance nightmare. It was susceptible to rock slides, roadbed slippage, heavy snow, and fallen timber. Once the traffic evaporated and through Gassaway-Charleston trains ceased during the late 1970s, this roughly twenty-three mile stretch of railroad became expendable if for no other reason than eliminating maintenance. With no on line customers remaining, B&O (Chessie System) opted for abandonment and subsequently removed thirty miles of track in 1981. Only ghost trains traverse the Bends of the Elk today.

In compiling images for this section, my regret is that I did not have time to take more photos. This area is difficult to access and daylight was ebbing quickly in addition to a considerable amount of territory to cover. At a future date, I will obtain more images in addition to archival ones that will be inserted.

Camp Creek (Procious)

This location is where WV State Route 4 parts from the Elk River running east to bypass all of the bends thereby reducing highway mileage to Clay where it meets the river once again. The Camp Creek location is probably better known by Procious and in the distant past was referred to as Camp Procious. It is representative of the number of small communities that settled by the creek mouths along the river. The B&O main line passed through here but there is no evidence of any customers or sidings that existed here. This is the west gateway to the Bends of the Elk.

|

Arched stone bridge across Camp Creek. This type of structure was common over small streams along the railroad right of way where long spans were not necessary. Looks like improvising was in play to use the understructure as a route for a utility line. Image courtesy Jesse Belfast/submitted by Timothy Zinn

|

This 1982 image was taken at the former grade crossing at Camp Creek. The view is westbound and reveals how the right of way looked one year after the track was removed. Dan Robie 1982

|

|

This view is eastward around a bend at Camp Creek and of significance here is the mile post that remains. Quite a number of these have been removed since the railroad was abandoned thirty years ago and finding this one was a surprise indeed. Dan Robie 2013

|

At the east end of Camp Creek, the roadbed turns and heads eastbound through the Bends of the Elk. At this point, the railroad was entering extremely remote territory. The appearance of the roadbed here is exactly how all of the right of way looked after the track was removed in 1981. A bare and black sub bed revealing the years of coal hauling and resulting slag that accumulated. Dan Robie 2013

|

Rouzer

Rouzer was a flag whistle stop for both the Coal and Coke Railway and later for the B&O in its early years of ownership of the line. A passing siding was located here for train meets when traffic volume was higher and during the era of passenger trains. It was long gone by the latter years of the B&O.

|

A view of storage tanks taken from across the Elk River near Rouzer. The railroad roadbed is visible in the background. Dan Robie 2013

Below: The original stone culvert over Birch Run was damaged which led to its replacement by the B&O. At some point--probably the 1940s when other bridge piers were replaced on the line--this utilitarian squared culvert was constructed at Mollie. Image courtesy Jeanie Droddy/ Herb Wheeler collection

|

Mollie (Birch Run) |

|

Originally known as Birch Run, this flag stop station once hosted a post office that in 1912 was run by a postmistress by the name of Mollie Procious. Shortly thereafter, Birch Run was renamed in her honor and the location simply became known as Mollie. Railroad timetables continued to list the locale as Birch Run so the name Mollie must have only been used by area residents and for postal purposes. Aside from this bit of trivia, the location held no special significance for the B&O as it was merely a location along the route. Mollie is identified on the topographical map in blue.

|

Shelton

|

Shelton was another of the small place names located at a creek mouth. This tiny community, situated at the mouth of Little Sycamore Creek, was a location of a small station (B&O call letters SN) that was gone by 1938. The B&O had a passing siding located at Shelton that eventually disappeared with the decline of traffic. During the steam era, Shelton was also a water stop.

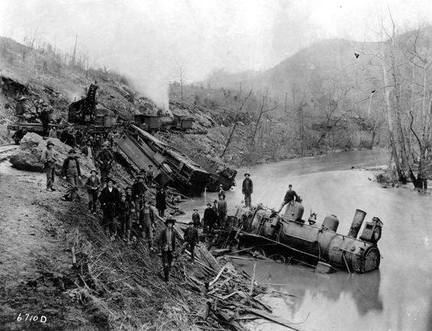

1907 derailment during the Coal and Coke Railway era between Shelton and Big Sycamore (Dorfee). Heavy rains washed out a section of track causing this train to plunge into the Elk River. Tragically, the engineer was trapped and died from drowning. Image courtesy Annie Bradt

|

Big Sycamore and Dorfee 1942 Derailment

On August 23, 1942, the world was in a state of chaos. Nazi Germany occupied the majority of Western Europe and was bogged down in the Soviet Union. In the Pacific Theater, America was battling the Japanese in the Solomon Islands at a place called Guadalcanal.

Half way around the globe and in a dramatically different world, B&O train #87 departed Clay with twenty-five cars bound for Charleston. There was nothing especially out of the ordinary on this particular date except for the heavy rains the area had received. Train #87 was delayed in departing Clay but there was no overt concern except for that it would arrive in Charleston later than scheduled. Upon departing, the crew surely observed the Elk River and must have wondered if the recent rain would create any problems for residents and railroad alike. But trouble can be where one least expects and it would come not from the Elk River but from a tributary, Big Sycamore Creek. As Train #87, led by engine #2814, an E27c Consolidation, ran the track that followed the curvy contour of the river, little did the crew know what lay ahead.

The world was in turmoil. On this date, the B&O would face a tragedy of its own near a whistle stop named Dorfee in Clay County, West Virginia. Train #87 would not arrive in Charleston on this day in 1942.

Half way around the globe and in a dramatically different world, B&O train #87 departed Clay with twenty-five cars bound for Charleston. There was nothing especially out of the ordinary on this particular date except for the heavy rains the area had received. Train #87 was delayed in departing Clay but there was no overt concern except for that it would arrive in Charleston later than scheduled. Upon departing, the crew surely observed the Elk River and must have wondered if the recent rain would create any problems for residents and railroad alike. But trouble can be where one least expects and it would come not from the Elk River but from a tributary, Big Sycamore Creek. As Train #87, led by engine #2814, an E27c Consolidation, ran the track that followed the curvy contour of the river, little did the crew know what lay ahead.

The world was in turmoil. On this date, the B&O would face a tragedy of its own near a whistle stop named Dorfee in Clay County, West Virginia. Train #87 would not arrive in Charleston on this day in 1942.

At left: The crew of B&O E-33 class 2-8-0 #2939 poses for a portrait at Gassaway circa 1930s. Engineer "Pat" Paisley is second from left. At right, "Pat" Paisley in a family portrait taken June 1942--two months before that tragic day at Big Sycamore. Photos contributed courtesy Annie Bradt

Eight miles west of Clay, Train #87 was running at 25 MPH as it passed one of the whistle stops in this remote area at Dorfee. As the train approached the deck bridge that spanned Big Sycamore Creek, the engineer suddenly applied the brakes placing the train in emergency. Upon hitting the east end of the bridge, engine #2814 suddenly leaned to the left and plunged from the bridge and lodged in the creek bed on its left side towards the west end of the bridge. Eleven of the twenty-five cars left the track and followed the locomotive into the creek creating an abysmal mess as cars piled upon each other with a number of wheel trucks breaking loose and scattering about.

Above and below: A series of photos capturing the aftermath of the tragic derailment at Big Sycamore Creek in August 1942. These images contributed courtesy of Annie Bradt whose grandfather was the engineer who perished on that fateful day.

|

“The engineer was my grandfather. His name was William Eugene "Pat" Paisley of Gassaway, W. Va. He was my mother's father. His wife, Edith told us that the run was not his normally. It was Sunday, his day off and he had a migraine. The engineer who ran the route called in sick. The man who checked the abutment under the bridge was gone that day.

|

And you know the rest. After several days, his body was found under the load of coal that had trapped it to the creek bottom. He had been a good swimmer. His body was taken to the funeral home to be embalmed as the bodies had turned blue. He was then taken to their home at 193 Braxton Street, Gassaway, where his brave and heartbroken 54 year old wife and mother of their 5 children, insisted on holding open the door as he came home one last time.”-Annie Bradt

Tragically, of the five man crew on this train, three lost their lives in this accident---the engineer ("Pat "Paisley), fireman, and front brakeman. The conductor and flagman survived without injury having been at the rear of the train in the caboose.

The ghostly location of Bridge 41.1 across the mouth of Big Sycamore Creek. The left, or east, pier was under washed by high water from the creek causing Train #87 to derail and run off the bridge in August 1942. (These piers are the replacements) Seventy years later, one could probably find traces from this terrible derailment buried in the creek bed. Dan Robie 2013

Extensive investigation determined that the cause of the derailment was a structure failure on the Big Sycamore Creek bridge, identified as Bridge 41.1 by the railroad. High water caused by the recent heavy rains had undercut the east pier of the bridge rendering it with no support. When the locomotive hit the east approach, its weight caused it to simply roll over to the left. The pier washout had occurred rapidly for another westbound train bound for Charleston crossed the bridge four hours earlier without incident.

The area at Dorfee and Big Sycamore hosted coal mining activity during the early 1900s. Two recorded operators and shippers here were the Kanawha White Ash Collieries and the Thompson Block Coal Company. An exploration of the area may reveal telltale clues of their one time existence.

Yankee Dam-Elkhurst

|

During the 1830s, a group of settlers from the Northeast moved into the area and constructed a dam in the Elk River in the vicinity of Blue Knob Creek. A mill and factory were also built and lasted until it was washed away by flood waters . Later, another group of people from Nova Scotia settled in the area, rebuilt the community and the name was changed to Elkhurst. Coal mining existed here during the early 20th century and at least three separate companies operated here. The listing includes the Big Block Coal Company, Elkland Coalmining Company, and the Jones-Winifrede Company Steidal mine.

Elkhurst was the location of a passing siding and a flag whistle stop for passenger trains. The siding was gone by the latter years of the B&O and on line freight no longer originated or terminated here. A coaling location was also located in this vicinity during the steam era. An unidentified rural church adds to the rustic setting at Elkhurst. The right of way here is wider where it accommodated the main and passing siding of a now vanished railroad. If only we could step back in time with a camera here and an approaching train. Image Jeanie Droddy/ Herb Wheeler collection

This was the location of the Elkhurst passing siding that the 1950 Thanksgiving Train #136 tied down at due to the unexpected blizzard. Ironically, a nearly identical event in 1944 led to another train sitting in the siding here due to heavy snow. Unless one was living in the area at the time or is a historian, the significance of this location is lost to time. Dan Robie 2013

|

A good portion of the Hartland-Elkhurst Road has utilized the former right of way as is pictured here. Any roadside markers such as mile post or whistle posts have long since vanished. Dan Robie 2013

Elkhurst Buried in the Snow 1950n 1950, the Cold War was in full bloom and it had become hot due to the erupting conflict in Korea. The southern portion of the peninsula had been invaded by northern Korean Communists but appeared to have been thwarted by United Nations troops. By the autumn, all indications were that the hostilities would soon end and the crisis resolved. On Thanksgiving weekend, it all changed. A massive invasion by the Chinese intensified the conflict and ensured that war would continue.

On that very same weekend, B&O passenger train #136 departed Charleston, WV and would soon engage in a battle of its own. The enemy it faced was Mother Nature and she was to manifest herself in the form of one of the largest snowfalls on record. In an odds defying case of deja vu, nearly identical circumstances had occurred six years earlier 1944 with another eastbound passenger train from Charleston. The Thanksgiving weekend of 1950 began with rain that with the dropping temperatures quickly changed to snow. And it kept snowing all night and into the following day in the form of white blankets. Soon, all communication was lost but Train #136 although delayed departing Charleston, commenced on its run to Grafton. As the train ran eastward, the heavy snow had created drifts and by the time it reached Clendenin, the depth of the snow increased considerably. The Elk River line hugs the south bank of the river and as one travels eastward from Clendenin, the hillsides adjacent to the track become steeper creating pockets for heavy snow drifts and accumulation. There is also the danger of falling timber from the weight of the snow. Train #136 on this day faced a decision whether to continue on to Grafton and due to the number of passengers, it proceeded east.

|

Once in the remote region between Clendenin and Clay, the train encountered heavy snow drifts and stopped on occasion to clear fallen trees. Another concern facing the crew was that the steam locomotive was nearing an alarmingly low water level. The crew decided it best to pull the train into the siding at Elkhurst. As time passed, there was growing concern in Gassaway as to the whereabouts of the train. Since communication was down, its location and disposition was a mystery. Train #136 was lost.

The following morning, a search train was dispatched from Gassaway in search of the lost train. Not only was there danger of the track condition, but running the line blind and meeting #136 head on was a concern as well. The search train ran as far west as Clay as it, too, encountered snow drifts and fallen trees and the hunt that day ended. The quest for #136 resumed the next morning.

Upon the return to Clay the next day, the train had not passed but it was determined be located several miles west at Elkhurst. The search train continued onward to that location whereas the #136 was discovered virtually buried in the snow. Obviously, the primary concern was for the crew and passengers but the crew had managed to keep the locomotive under fire to provide heat and security from the elements. Food had been provided by the Elk River Coal and Lumber Company and coffee from the Girls of the Elkhurst 4H Club. Finally on the next day, a relief train arrived and took the #136 on to Gassaway ending a saga that for all who had been involved would not soon forget.

|

Looking over the bank at the track and its proximity to the Elk River. This location is almost at the 1981 Chessie System sever point between Elkhurst and Hartland. The track extends only a few hundred feet beyond this scene to the cut point. Dan Robie 2013

|

Another view of the dilapidated track close to Hartland. The size of trees growing between the rails adds emphasis to just how long it has been since a train was here. In all likelihood the wreck out trains that pulled the track between here and Reamer three decades ago were the last ones to pass. Dan Robie 2013

|

|

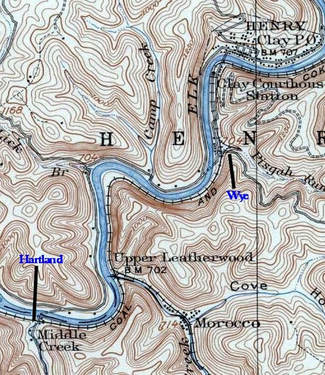

The 1907 topographical map caption here focuses on the area from Hartland to Clay. Note on this map from the Coal and Coke Railway era that Hartland is referred to as Middle Creek and that there is no rail line following that creek as the Middle Creek Railroad had not yet been built. The town of Clay was known as Henry then Clay Court House (railroad listing) and ultimately, simply Clay.

|

Hartland

There is no reference to the community of Hartland on the topographical map from the early 1900s but sometime during the interim, the region at the mouth of Middle Creek acquired the name. Early timetables also referred to the location as Middle Creek, a name which would gain more prominence as a coal company operating along the watershed of the creek. In addition to the mining along the Middle Creek watershed, other operators tapped this rich pocket of black diamonds in the vicinity. A listing of others coal companies from the early B&O era includes the B. E. Ray Coal Company, Lima Coal Company, and the Mid-Lothian Jewel Coal Company.

It is June 1947 and B&O P3 Pacific #5123 leads Train #37 west through Hartland bound for Charleston. In the distance is the WV Route 16 bridge and the connection with the Middle Creek Railroad. Unique location on a rarely photographed line. Richard J. Cook photo/ courtesy Allen County Museum All rights reserved

The Middle Creek Coal Company operated four mines----LeMoyne, Rainbow, M.L.C, and Osborne--- along a branch line that went by the same name, the Middle Creek Railroad, which began operating in 1925. Connecting with the B&O at Hartland, it ran several miles to the Clay County community of Bickmore. This operation generated coal traffic for the B&O until 1951 when three of the mines closed down. The B&O continued to serve the one remaining mine (LeMoyne) until it played out and the trackage of the Middle Creek Railroad was officially abandoned in 1965.

|

Westbound overhead view of the track at Hartland. Just as in the previous views west of here towards Elkhurst, the track is choked with growth. Seems incredible this was once a moderately busy railroad with scenes such as this. Dan Robie 2009

|

Stone arch bridge spanning the mouth of Middle Creek at Hartland. The railroad is visible on top although it is in dilapidated condition. Image Jeanie Droddy/Herb Wheeler collection

|

Westbound view at Hartland taken during the WV Route 16 bridge construction in 1924. A rare look at this discreet location with the B&O main at right and the Middle Creek Railroad diverging to the left. This time period was the heyday of the MCR and the mines at Bickmore. Image West Virginia and Regional History

|

Eastbound view of former B&O from Hartland. The Middle Creek Railroad connection is still intact as it is diverging to the right. Moving eastward in the Elk Valley, evergreen trees become more prevalent and specifically the hemlock. Dan Robie 2009

|

Another view as above except for a different vantage point. The poor condition of the track here is apparent and the roadbed to the river side of the track has eroded beneath the ties. Dan Robie 2009

|

When the B&O filed for abandonment of its line between Hartland and Reamer twelve years later, this location became the end of the line that extended west from Gassaway. It is curious that Hartland was selected as the sever point since there was no on line traffic from it eastward through Clay to Dundon at the junction of the Buffalo Creek and Gauley. Apparently, B&O (Chessie System) elected to keep the line intact from Clay to Hartland in the event any mining would redevelop along Middle Creek. Aside from this possibility, there would appear to be no other reason to as to why this stretch of track remained.

|

Hartland was a busy junction during the era of the Middle Creek Railroad. 2-8-0 #2, pictured here in 1935, transferred many hoppers of loaded coal to the B&O during its service life. Image courtesy Gray Lackey

|

Photos taken of the Middle Creek Railroad are scarce. Pictured here is 2-8-0 #1239 during the twilight of operations on the MCRR at Hartland in 1948. This locomotive--- purchased second hand--is a former B&O E8 class Consolidation. Image courtesy Gray Lackey collection

|

|

The remnants of the Middle Creek Railroad south of its connection to the B&O at Hartland. Central West Virginia once boomed with the extraction of natural resources such as coal, gas, and timber. These resources in turn created other industrial jobs that refined or processed them. Gone are the days. Dan Robie 2013

|

The Middle Creek Railroad paralleled the stream for several miles to serve coal mines towards Bickmore. Pictured here is the remnant of a bridge spanning the creek south of Hartland. Image Jeanie Droddy/ Herb Wheeler collection

|

Today, track remains at Hartland but is in severely dilapidated condition from non-use and maintenance for many years. Perhaps the last train ever to be at this location was in 1981 when the track removal was taking place. The railroad and right of way here now is under the ownership of TERRI (The Elk River Railroad) which acquired the ex-B&O trackage from Gilmer to Hartland during the early 1990s.

|

Detail is obscured by growth but this is the deck bridge that spans Upper Leatherwood Creek between Clay and Hartland. Bridge remains intact because the railroad was left in place extending west to Hartland. Steel bridges were built to cross the larger creeks on the route with the deck style the preferred choice. This type of bridge was also used at other locations such as Big Sycamore, Morris Creek, and Queen Shoals which were removed years ago when that sector of railroad was abandoned. Image Jeanie Droddy/ Herb Wheeler collection

|

Clay

Located roughly at the midway point of the railroad between Charleston and Gassaway, Clay was a prominent location along a line that was dotted with small towns and sparse population. Incorporated in 1895, it is the only other community aside from Clendenin with that distinction between the two endpoints. As was the case in the naming of many counties and communities in the early history of the United States, the origin was often a notable individual. “The Great Compromiser”, Henry Clay, prominent 19th century United States Senator and Vice President, is the namesake for both the town and county here.

Looking east through the town of Clay as it appeared in 1917. The court house is visible at left with homes spaced about on the north bank of the Elk River. This was the era that B&O took control of the Coal and Coke Railway and the railroad is visible on the opposite bank of the river. Not visible (unfortunately) in this scene is the Clay depot. Image West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey.

For many years, the town of Clay was referred to as Henry then Clay Court House. Railroad timetables list the location as such beginning with the Charleston, Clendenin and Sutton Railway and this continued after the acquisition by the Coal and Coke Railway in the early 1900s. At some point and well into the B&O era, the “Court House” was dropped and the location simply referred to as Clay. The town was briefly the terminus for the railroad built from Charleston for several years until construction was eventually continued eastward in the waning years of the Charleston, Clendenin and Sutton Railway until its eventual envelopment into the Coal and Coke Railway.

Former B&O looking west at the west end of Clay. Many years ago, there was a wye beyond the structure at left that was used to turn steam locomotives to face the direction from which they came. The track condition here is obviously bad with rusted rail and rotten ties but is free of heavy growth. Dan Robie 2013

The heyday for Clay in relationship to the railroad was when the passenger train was in full bloom. Although it lies in a region rich with natural resources there was little online business for the B&O generated here despite its strategic location between two branch lines that connected to the railroad. The Middle Creek Railroad to the west at Hartland and the much larger Buffalo Creek and Gauley to the east at Dundon flanked the town of Clay in terms of the railroad. At the turn of the century, there was also a logging line that ran along Leatherwood Creek just to the west of town at Upper Leatherwood. Along with a depot (B&O call letters SO), a passing siding was located here and at the west end of town, a wye was constructed to turn steam locomotives for runs east or west. In its 1948 listing of industries, B&O named York Mine No.1 and the Maryland and West Virginia Lumber Company as customers in the vicinity. Earlier coal firm shippers included Clay-DeBerry Leonard Mine and the Standard Kanawha Coal Company.

Ironically, the larger part of Clay was located on the north bank of the Elk River opposite the railroad. When the community was established, this side of the river had the wider plain in the narrow valley and the development was greater than on the south bank. Of course, this predated the construction of the railroad but as a result, the main body of Clay was not traversed by the railroad.

Ironically, the larger part of Clay was located on the north bank of the Elk River opposite the railroad. When the community was established, this side of the river had the wider plain in the narrow valley and the development was greater than on the south bank. Of course, this predated the construction of the railroad but as a result, the main body of Clay was not traversed by the railroad.

|

The west end of the passing siding at Clay. B&O timetables in the twilight years of operation listed this as an active siding although by the 1970s its viable use would have been for maintenance of way equipment or bad order cars. The east end connection to this siding has been removed. Dan Robie 2013

|

A view looking west at a section of track that had been removed. This track removal post-dated the Chessie System track removal of 1981 so it was done sometime in the interim by a third party. The east connection to the Clay passing siding would have been in the extreme distance. Dan Robie 2009

|

Today, traces of the B&O exist at Clay although ownership is now under the Elk River Railroad. The track here is in a ruinous state and has been removed at sporadic locations in the area by other entities. Realistically, if the Elk River Railroad (TERRI) ever reactivates the railroad west of Gassaway, the section from Dundon to Hartland likely would not be rebuilt to operational standards. The real pot of gold for this to occur would be a complete rebuild west to the Blue Creek area to secure a route to Charleston. Considering all circumstances and present economic climate, it is more fantasy than probability.

|

East view of former B&O track swinging around a curve toward the grade crossing and river bridge that connects Pisgah Road to the business district of Clay. Abandoned railroad is not totally without use as it appears to make a solid prop to cut firewood. Dan Robie 2009

|

East view at the grade crossing of the B&O entering Clay. This scene is typical of the railroad with the river on the north side and hills or creek hollows on the south. Beyond this curve about a mile away is arguably the most noted railroad place name community the line passed between Charleston and Gassaway. Dan Robie 2009

|

On to Gassaway

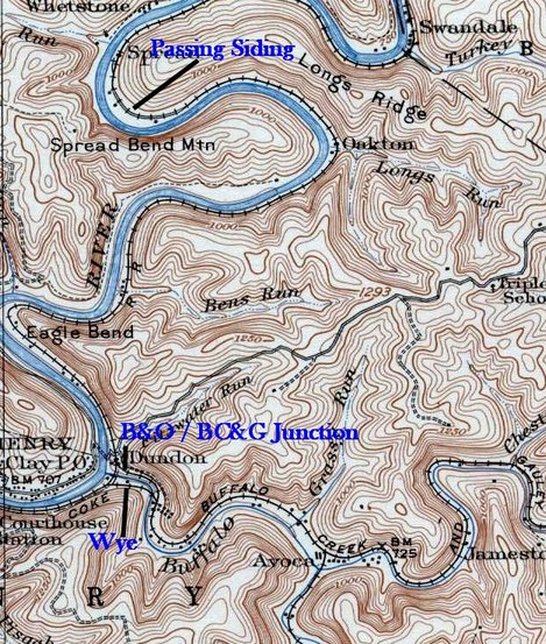

)The region of the railroad between Dundon and Gassaway was the busiest both during the Coal and Coke Railway years and later the B&O. It is also the best known and documented section of the route between Charleston and Gassaway due in no small part to the Buffalo Creek and Gauley Railroad and its connection at Dundon. The Buffalo Creek and Gauley (BC&G) was among the most unique short lines to operate in America generating car loads of coal to interchange with the Coal and Coke, B&O and, finally, the Elk River Railroad. It was also a mecca for railfans during the late 1950s through early 1960s due to its use of steam locomotives after the Class I railroads had already transitioned to diesels.

Gassaway was the hub of operations for both the Coal and Coke and later B&O. It was the prototypical small town centered on the railroad in that its fortunes were directly aligned with it. The steam era years were peak as this translated into more operation which equaled more jobs. Once the B&O converted to diesel power, facilities were eliminated, and with the passing of years, the tempo of operations declined. By the 1980s, Gassaway was but a shell of its former self and once B&O/Chessie System was consolidated into CSXT, the existence of the railroad along the Elk itself was in jeopardy. CSXT was quick to shed the remaining B&O from Gilmer through Gassaway west to Hartland. Had not the Elk River Railroad (TERRI) been formed, fate would indicate that this remaining track would have been scrapped. Today, the railroad lives on in a near state of dormancy with car storage in the Gassaway and Frametown area as the only source of revenue. TERRI hopes for the day when revenue trains can run the line once again although with the current political, environmental, and economic climates, that day is clouded within a pipe dream.

Between Dundon and Gassaway, the railroad echoed the scenic Elk River bend for bend passing through small communities with colorful names and charms of their own. Place names such as Otter, Groves, Duck, and Strange Creek can be found along the river passing through Clay and Braxton Counties. As with the region west of Clay, most of these are situated at the mouth of creeks and were of more importance to the B&O during the era of passenger trains.

|

The area covered in this chapter except for Dundon is one I seldom saw except for the early 1980s when my work would occasionally direct me to this region. My recent outing (2013) to photograph specific locations was the first time I had revisited the area in more than twenty years.

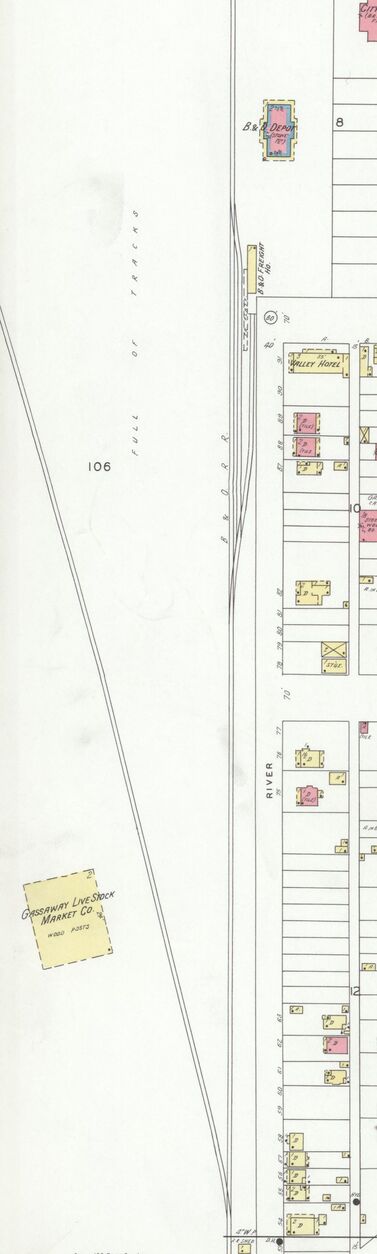

This section of the 1908 topo map focuses on the railroad just east of Clay to past the bend beyond the Spread passing siding. Without question, the highlight here is at Dundon and the connection with the Buffalo Creek and Gauley. The wye connection is noted at Dundon as it existed during the Coal and Coke Railway era. Aside from the wye removal, all else here remained the same during the B&O tenure.

|

Dundon

Google Earth view of the B&O/Buffalo Creek and Gauley Railroad junction at Dundon and surrounding topography. Once the busiest location on the B&O between Charleston and Gassaway, coal from the Clay County mines funneled to the B&O from the BC&G and successors for many years. A wye once existed here with a track leg connection on the west bank of Buffalo Creek.

With the possible exception of Gassaway, no location along the B&O Elk River route was more notable than Dundon. The irony here is that the centerpiece was not the B&O itself but the connecting short line Buffalo Creek and Gauley Railroad instead. The BC&G was a unique railroad by any measure. First of all, it was the largest source of traffic for the B&O between Charleston and Gassaway. More notably, it earned a special place in the accords of rail enthusiasts as it operated steam locomotives after the B&O and the other Class I railroads had switched to diesels. During the late 1950s until the end of steam on the BC&G in 1963, Dundon was a rail hotspot with fans nationwide visiting and watching the operations. This was the true testament despite an era when the region was more difficult to access predating the Interstate highways. Not be lost in the shadows of the BC&G, the Elk River Coal and Lumber (ERC&L) line connected with the BC&G and contributed to the interchange traffic to the B&O.

|

Westbound view of the B&O truss bridge crossing Buffalo Creek at Dundon as it was in 1990. Even twenty plus years ago, the dormant condition of the track in this scene is apparent. In the distance to the left can be seen the route of the former wye connection that was removed many years ago. Dan Robie 1990

|

A low angle view of the Buffalo Creek bridge taken from the west bank of the stream. During the recent past railings were added for use as a walkway across the span. The stillness is an eerie contrast to the sound of trains once so prevalent here. Image by Jeanie Droddy

|

Contemporary view of the former B&O/ BC&G junction at Dundon looking east. B&O is directly into the curve and the BC&G diverges to the right. Image Jeanie Droddy/ Herb Wheeler collection

As for the B&O operation at Dundon, it was effectively an interchange point for the BC&G. The loads moved east to Gassaway with empties moving west on the return. The siding at Dundon was heavily used by both BC&G and B&O for staging cars and to run around them. In the distant past, there was a wye at the Dundon interchange. The north leg connected to the B&O west of the Buffalo Creek bridge then crossed the creek to connect with the BC&G main. This connection was removed leaving only the eastern junction on the east bank of Buffalo Creek near the Dundon depot (B&O call letters DU). Dundon was a passenger train stop with the Coal and Coke Railway and lasting through the B&O era of passenger service.

The Elk River Coal and Lumber Company at Widen as it appeared in 1918. Located at the end of the Buffalo Creek & Gauley Railroad, this was the largest operator in Clay County and generated substantial carloads for both the Coal and Coke Railway and B&O at Dundon. Image from The Black Diamond

I will defer the operations of the BC&G here as there are other sites and books that give it the detailed scrutiny that it deserves. Listed in the closing credits of this page will be sources that will direct the reader who is interested in reading about the Buffalo Creek and Gauley and the Elk River Coal & Lumber RR.

Vintage scene at Dundon in August 1953. Q-3 2-8-2 Mikado #4577 leads what is likely westbound Train #81 from Grafton to Charleston past the depot. The period automobiles further flavor this already classic image. Photo Richard J. Cook/Allen County Museum

B&O fortunes at Dundon mirrored the BC&G. When the BC&G operated, the B&O had business there. When the line closed in 1965 until reopening with Majestic Mining in 1971, Dundon reverted to a place name trains passed between Charleston and Gassaway. During the mid-1970s, B&O train #62 from Charleston would frequently pick up coal loads at Dundon on its return to Gassaway.

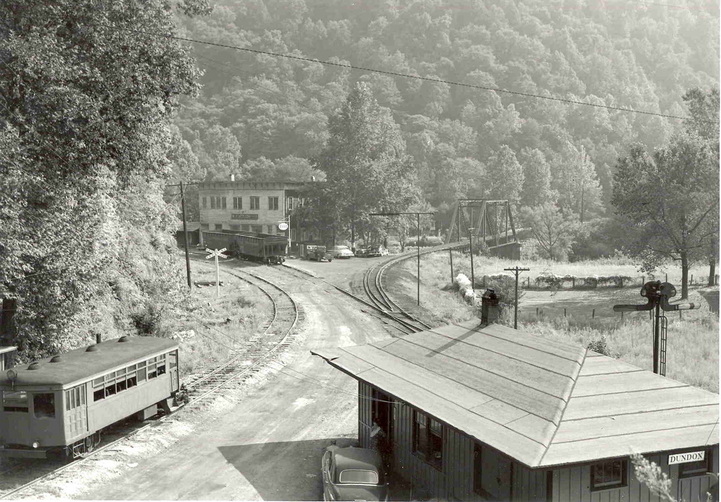

Then....Dundon circa 1950s |

Now.....Dundon 2009 |

|

This wonderful image freezes Dundon in a happier time and is loaded with detail. To the left is a BC&G railbus passing by the B&O Dundon depot. In the distance is the old company store and hoppers sitting on the BC&G main. The B&O main line diverges to the right with the truss bridge across Buffalo Creek. Jack Armstrong photo/courtesy Buffalo Creek and Gauley.com

|

This view from nearly the same point of view a half century later offers a striking contrast to the bygone era at left. The only similarities that remain are the outline of the track and the B&O truss bridge. Very little here to remind one that this was once a rail hotspot bustling with activity. Dan Robie 2009

|

Once through freight service to Charleston ended by the late 1970s, Dundon in effect became the western terminus of operations from Gassaway for the B&O. When Majestic Mining ceased operation in 1985, Dundon reverted to a state of rail idleness until the late 1990s when the Elk River Railroad began hauling coal off the old BC&G again. The operations were short lived and Dundon is once again a location of rusting rails and rotting ties as it has been for the past decade. Former B&O rails exist in a state of dilapidation and the only movement at present is the hope of restoring the former BC & G as a tourist line.

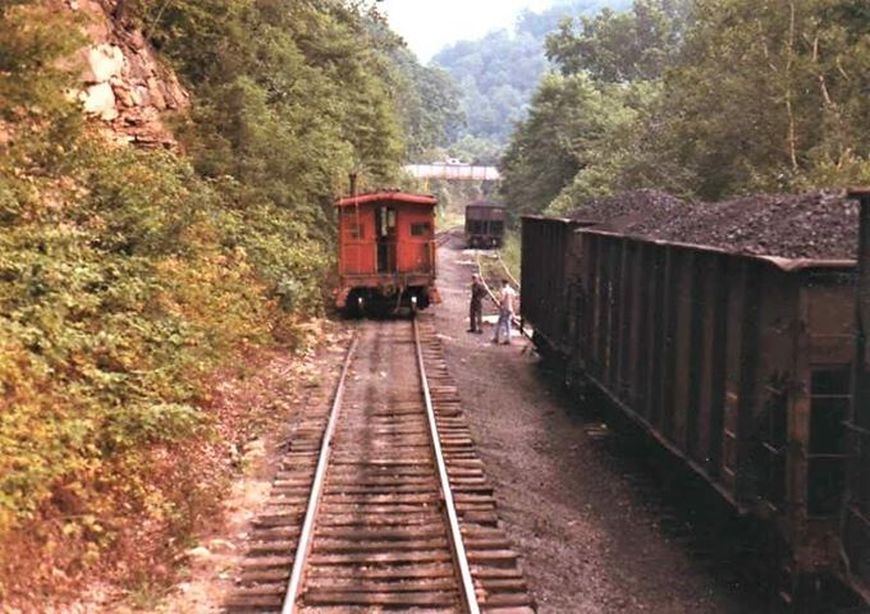

Dundon Gallery.....1980

The following group of photos are from the collection of Robert Slavy, a long time railroad photographer in West Virginia, taken during 1980. This was a few years after the B&O ceased as a through route to Charleston but activity abounded at Dundon at the former Buffalo Creek and Gauley Railroad interchange with operations at Majestic Mining. My gratitude to Mr. Slavy for the privilege of sharing his work on this page.

|

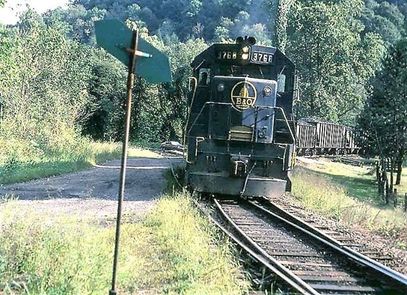

B&O GP40 #3768 leads a coal train across the Buffalo Creek bride at Dundon. Mr. Slavy stated this train was from a loadout at Hartland. Robert Slavy 1980

|

The#3768 backs onto the former BC&G to pick up loaded hoppers from Majestic Mining. Note the switch stand flags both on this image and the one at left. Robert Slavy 1980

|

B&O GP40 #3768 and a Chessie mate underway eastbound on the B&O main beneath the road bridge that spans both the railroad and Elk River. The Dundon passing siding/BC&G interchange is the diverging track. Robert Slavy 1980

|

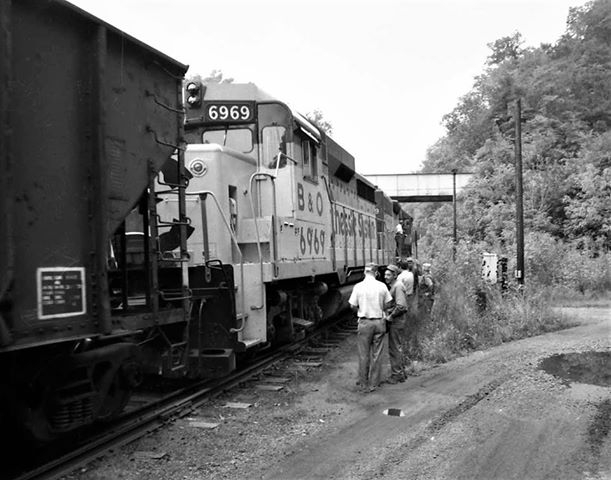

B&O GP30 #6969 in Chessie paint is a trailing unit on this train facing east. The Dundon depot once stood in the area on the far right. Robert Slavy 1980

|

B&O GP9 #6531 is in the passing siding at Dundon with a cut of hoppers. This locomotive was on lease to Majestic Mining from the B&O. View is eastbound on the main and captures the tight space between the hillside and river. Robert Slavy 1980

|

B&O caboose sits on the main and the hoppers are in the passing siding looking west. This photo is loaded with old time charm and the human element in this group of photos further enhances the scenes. Robert Slavy 1980

|

This 2009 image looks east from the Dundon bridge at both the B&O main (right) and passing siding. (compare with the Robert Slavy photo above at the same location) The area between the tracks appears to be converted to a road. It is a good bet that B&O seldom used this siding for train meets since it remained busy with the BC&G interchange. Meets would have been more likely arranged at the next siding east at Spread or west at Clay. Dan Robie 2009

|

Spread

The significance of Spread was as a passing siding location in a sharp bend of the river east of Dundon. Constructed during the Coal and Coke era, this siding remained active for the B&O well into the 1970s although by this date used for maintenance of way or car storage. This location was also a flag whistle stop during the passenger train era.

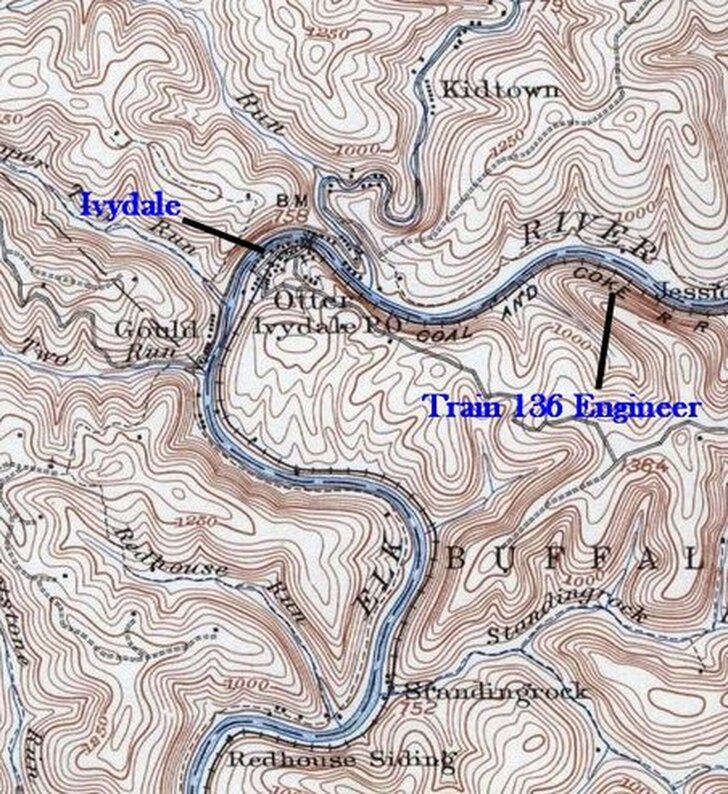

Moving eastward towards Ivydale (Otter). The Elk River continues to pass through bends but moving east, they become broader. There are few bridge crossings through this region to access the railroad and as a result, a scant number of images to share from this area.

Ivydale (Otter)

Otter was a full-fledged station stop for both Coal and Coke and through the passenger train era of the B&O. There is no record of any on line customers here for the B&O with the exception of its own freight depot (B&O call letter B). A siding was located at Ivydale and I have memories of it in use for storage during the early 1980s.

|

A 1982 view looking across the railroad towards the Ivydale Baptist Church. The siding is visible in this scene as is a Chessie System rail crane. Dan Robie 1982

|

Westbound view of track in use at this date. It was B&O when this photo was taken and the rails were shined with loads of coal coming from Majestic Mining off the old BC&G at Dundon. Dan Robie 1982

|

|

An eastward view of the railroad through Ivydale as it parallels Ivydale River Road. Track condition poor with coverings of weeds and under growth. Dan Robie 2013

|

These grade crossing flashers have stood dark vigil at the Ivydale Bridge crossing for well over a couple of decades now. Eastward around the curve the track is covered with heavy brush. Dan Robie 2013

|

Looking from the grade crossing through the Elk River bridge at the intersection of WV State Route 4. Shaded by both trees and time, it has been three decades since that grade crossing signal last flashed from a passing train. Dan Robie 2019

Tragedy at Otter

Although they are few in numbers now, longtime residents in Clay and Braxton Counties may have heard about or even recall this incident from many years ago:

The winds of change were blowing in along the Charleston Subdivision of the B&O circa 1950. Diesels were beginning to appear and the last passenger trains to run the line between Charleston and Grafton, Trains 135 and 136 respectively, were making their final runs for they would be abolished in 1951. During these waning times, there was an engineer by the name of William Paxton who often was the regular on 135 and 136. Preceding the incident that follows, he had just taken 135 into Charleston and during the layover, it was it was discovered that the regular fireman would not be able to make the return trip the following day on 136. On such brief notice, the railroad had no other alternative but to taxi another fireman to Charleston who could make the run east on 136. The fireman who would make the run with William Paxton on that day’s 136 was a relatively new employee on the B&O named Paul Duffield who to date had very little experience as a fireman. Once Train 136 departed Charleston for the run to Grafton, Mr. Duffield would later experience a traumatic occurrence that no railroad crewman would ever wish to experience.

The winds of change were blowing in along the Charleston Subdivision of the B&O circa 1950. Diesels were beginning to appear and the last passenger trains to run the line between Charleston and Grafton, Trains 135 and 136 respectively, were making their final runs for they would be abolished in 1951. During these waning times, there was an engineer by the name of William Paxton who often was the regular on 135 and 136. Preceding the incident that follows, he had just taken 135 into Charleston and during the layover, it was it was discovered that the regular fireman would not be able to make the return trip the following day on 136. On such brief notice, the railroad had no other alternative but to taxi another fireman to Charleston who could make the run east on 136. The fireman who would make the run with William Paxton on that day’s 136 was a relatively new employee on the B&O named Paul Duffield who to date had very little experience as a fireman. Once Train 136 departed Charleston for the run to Grafton, Mr. Duffield would later experience a traumatic occurrence that no railroad crewman would ever wish to experience.

Train 136 ran eastward from Charleston without incident on what had the appearances of just another daily run to Grafton. Stops completed at Clendenin and Clay and the smaller whistle stops in between. Eventually, the train arrived at the Otter (Ivydale) station stop for passengers and to take on water. Shortly thereafter, the train departed from Otter and Mr. Duffield was tending to his duty as fireman feeding coal to the 4-6-2 Pacific class locomotive. The train had achieved a good rate of speed when he noticed that Mr. Paxton, the engineer, had slumped forward and the fell from his seat. Obviously, there was something seriously wrong and immediately Duffield went to his aid. Upon examining Mr. Paxton, he determined that he had died and during these traumatic moments, the train was still under throttle and moving at a good rate of speed. Though shaken, Duffield repositioned Mr. Paxton in order to reach the throttle. Instinctively, he was able to close the throttle and apply the brakes bringing the train to a stop.

Serving as conductor on this train was Charley Cogar who was also a qualified engineer. He had been summoned by Duffield to the engine cab where he confirmed that Mr. Paxton had indeed passed on. Cogar then assumed the role of engineer and took the train to Frametown where railroad officials were immediately notified of the tragic events. Paul Duffield was a hero this day in that he responded to a tragic situation under traumatic circumstances with little experience and averted further tragedy by preventing a train derailment. There is no doubt the memory of this fateful day remained throughout his life. This account and two others, Big Sycamore Derailment and 1950 Elkhurst Trapped in the Snow, are but three documented events that occurred along this railroad. There are without question uncounted other ones that were not recorded and remained only in the memories of those men who were party or witness to them. Sadly, most of those accounts will be lost to the ages for so many have passed from the scene now.

Moving eastward through Groves, Villa Nova (Duck), Strange Creek and Glendon. These locations were station and flag stops for passenger trains with little on line traffic except for logging lines that ran along Groves and Strange Creeks early in the 20th century.

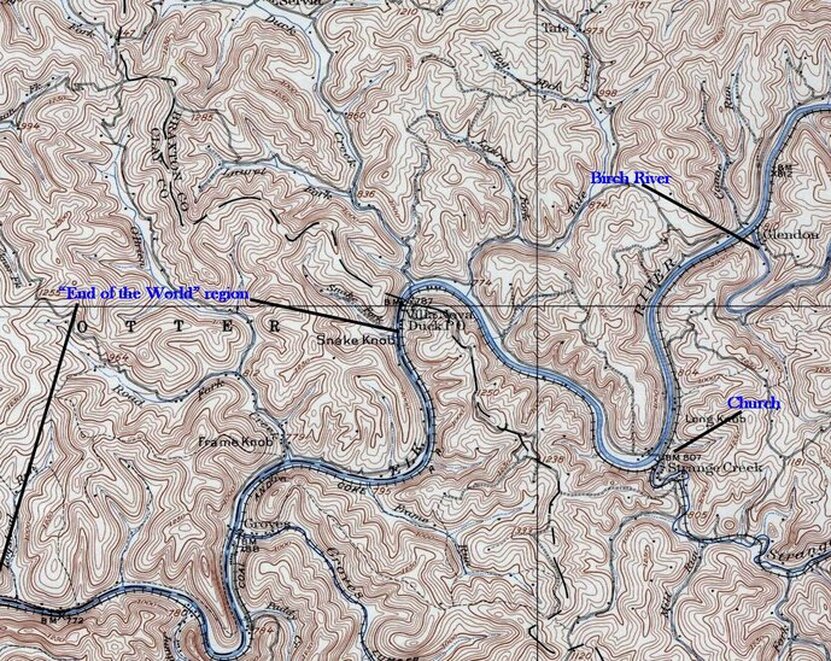

"End of the World"

The beautiful Elk River at a location in the "End of the World" section. Dan Robie 2013

The eloquent W.E.R Byrne from his book Tale of the Elk:

"The Elk River, seventy miles above its mouth at Charleston, in that wildly picturesque portion of central West Virginia, makes an abrupt bend in its course, where the waters, now with impetuous rush, now in placid pool, are baffled and turned to the right in a graceful semi-circular sweep of almost a mile, by beetling cliffs rising sheer from the river level, to an elevation of several hundred feet. These cliffs and their huge rocks, which, in the ages, have fallen away and found lodgement in and along the side of the stream, to the pioneer raftsman, as his craft swept into the curve from upriver, gave the distinct impression of having reached an insuperable barrier to his further progress--a cul-de-sac, or the jumping off place; hence from the earliest history of the country, that locality has been called, and still bears the name---"The End of the World". The beautiful river and the fishing shack nearby at the lower extremity of the curve described, where the curvature reverses and turns the other way with scarce less freakish trend, are the subject of these verses. "To him who in love of nature holds communion with her visible forms and can both speak and interpret her language--these lines are dedicated".

W.E.R Byrne (1862-1937)

Mr. Byrne was laid to rest in Spring Hill Cemetery at Charleston in a plot overlooking his beloved Elk River. As the railroad directly parallels the "End of the World" many folks, passenger and train crew alike, must have gazed upon the river here with sheer awe realizing it is a true marvel of creation.

The eloquent W.E.R Byrne from his book Tale of the Elk:

"The Elk River, seventy miles above its mouth at Charleston, in that wildly picturesque portion of central West Virginia, makes an abrupt bend in its course, where the waters, now with impetuous rush, now in placid pool, are baffled and turned to the right in a graceful semi-circular sweep of almost a mile, by beetling cliffs rising sheer from the river level, to an elevation of several hundred feet. These cliffs and their huge rocks, which, in the ages, have fallen away and found lodgement in and along the side of the stream, to the pioneer raftsman, as his craft swept into the curve from upriver, gave the distinct impression of having reached an insuperable barrier to his further progress--a cul-de-sac, or the jumping off place; hence from the earliest history of the country, that locality has been called, and still bears the name---"The End of the World". The beautiful river and the fishing shack nearby at the lower extremity of the curve described, where the curvature reverses and turns the other way with scarce less freakish trend, are the subject of these verses. "To him who in love of nature holds communion with her visible forms and can both speak and interpret her language--these lines are dedicated".

W.E.R Byrne (1862-1937)

Mr. Byrne was laid to rest in Spring Hill Cemetery at Charleston in a plot overlooking his beloved Elk River. As the railroad directly parallels the "End of the World" many folks, passenger and train crew alike, must have gazed upon the river here with sheer awe realizing it is a true marvel of creation.

Early photo of the rock cliffs at the "End of the World" with the B&O running along the river bank below them. A scene that existed in the time of W.E.R Byrne's exploits in the Elk River valley. Image West Virginia Geological Surveys

Groves

|

Not a vivid photo but still captures the "End of the World " region west of Groves. View is railroad west with the Coal and Coke Railway/B&O following the bends of the Elk River at left. Image West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey.

|

View from across the Elk River at the mouth of Groves Creek and the railroad deck bridge spanning it. Dan Robie 2013

|

Situated in the heart of the "End of the World" region, Groves was a flag whistle stop for passengers lasting into the B&O era. During the early 1900s, a small lumber railroad ran along the creek that connected to the Elk River line at the mouth of the creek.

Villa Nova (Duck)

Situated at the Clay-Braxton county line, this small community by either name was once served by a depot (B&O call letters VN) and a siding still exists at this location today although in disrepair as is the main line. The location was originally named Duck because of the flocks of ducks that would take refuge in an island in the Elk River near there. The place location used by the railroad dating back to the Coal and Coke Railway was changed to Villa Nova by Henry Gassaway Davis. He did not fancy the name of Duck as a stop along his railroad and therefore changed the name. The significance of why he selected Villa Nova is not recorded. B&O continued with the change using Villa Nova as the place name in its timetables.

|

A damaged 1982 print of a Chessie maintenance of way train in the siding at Duck. View is looking eastbound. Dan Robie 1982

|

The Chessie kitten was still purring when this 1982 image looking westbound at Duck was taken. The RC Cola sign was quite common in that era. Train time was still happening at Duck in these days with coal coming off the old BC&G. Dan Robie 1982

Left: Fast forward thirty years and from the opposite end of the store and this is the scene as it is today. Looking eastbound at track overtaken by weeds and a siding at left completely covered with earth and growth. One remarkable similarity in this photo and the one above from 1982 is that there is a school bus parked in the same location! Dan Robie 2013

|

It was this area that nearly led to a resurrected Elk River Railroad during the 1990s when the proposition of opening new mines in the region surfaced. Not only did this create the feasibility of generating traffic east to Gassaway but also west to Charleston with a rebuilt railroad west of Hartland. These hopes were dashed when the coal was discovered to not be of suitable quality.

|

Westbound view of the former B&O at---I'll use Villa Nova this time. Beyond the building at left, heavy growth once again smothers the railroad. Dan Robie 2013

|

Nothing symbolizes the rural grade crossing more than the crossbuck. These two are of different ages as the one facing the camera is of newer lineage. The Villa Nova siding is visible in this view. Dan Robie 2013

|

The Elk River Valley was populated with independent coal operators during the Coal and Coke Railway years lasting into the early B&O era. Although the region in Braxton County along the railroad was not as active with mining as neighboring Clay County to the west, there was sporadic mining scattered about. During the 1920s the W. A. Merrill Coal Company operated mines in the vicinity of Duck.

An idyllic view of both the railroad and river at Villa Nova (Duck). For a half century, passengers on trains of the Coal and Coke Railway and later B&O could gaze out the window and admire scenes such as this in the rustic Elk River valley. Image by Jeanie Droddy

Strange Creek

During the early 1900s, a rail branch line extended up the Strange Creek basin for the extraction of timber but as with many other logging lines, it soon disappeared. There was a depot located (B&O call letters SC) here until it was demolished in 1942. B&O had no customers located here but a stub ended siding was in place for storage purposes. The railroad crossing of Strange Creek is on a deck bridge.

|

Looking westbound across the Strange Creek deck bridge in the days when the B&O/Chessie System lived. Maintenance was minimal to the extent of keeping a low density line operable. Dan Robie 1982

|

A westbound view at the same location thirty years later. The angle is different because the afternoon sun was dead on directly across the span. Even with the winter season, the intrusion of brush is still apparent. Dan Robie 2013

|

Before....1982

|

After....2013

|

|

Eastbound view by the siding at Strange Creek. This was the location of the depot that was demolished in 1942. Shiny rails are reflective of the B&O active here operating trains to and from Majestic Mining on the former BC&G. Dan Robie 1982

|

This scene is relatively unchanged thirty years later except for the track condition and difference in seasons. It's probably a good bet that the Chevy pickup is long gone, though. There are piles of ties and rails here today from maintenance of way work done in years past. Dan Robie 2013

|

“Strange my name....And strange the ground...And strange that I...Cannot be found”

In 1795, surveyors from the State of Virginia came upon the bleached skeleton of a man and a dog found at the base of a beech tree in which the words above were inscribed. The man was William Strange and he became lost after being separated from his hunting party. Located at a creek mouth at the Elk River, legend has it that this how the creek and community received its name.

In 1795, surveyors from the State of Virginia came upon the bleached skeleton of a man and a dog found at the base of a beech tree in which the words above were inscribed. The man was William Strange and he became lost after being separated from his hunting party. Located at a creek mouth at the Elk River, legend has it that this how the creek and community received its name.

|

The fallen tree emphasizes the forlorn state of the railroad here. Track diverging to left is the stub end siding seen in the above images that terminated at the former depot site. Dan Robie 2013

|

Eastward view of the main line paralleling the road at Strange Creek. In most instances along this railroad, public roads tend to be closer to the hillsides with the track between them and the river. Dan Robie 2013

|

In a scene that is classic rural West Virginia, this view captures the former B&O running eastbound by the Strange Creek Independent Baptist Church. How wonderful it would have been to have a train in this frame with what is certainly one of the most beautiful rural churches I have seen. Dan Robie 2013

Glendon

Glendon was merely a place name for the B&O aside from a flag passenger stop many years ago. Early in the 1900s, there was a short siding located along the east bank of the Birch River. There is no indication what this may have been used for whether it was storage track or perhaps a small business.

Truss bridge on the former B&O crossing the Birch River at its confluence with the Elk. Two picturesque rivers in a serene setting equal a fisherman's paradise. Dan Robie 1990

|

Westbound view looking across the Birch River bridge. The old siding that existed at Glendon many years ago diverged to the left here before the bridge. Dan Robie 1990

|

Opposite view at Glendon running eastbound. The rusty rails during the time period concur with the idle transition period from Chessie/CSXT to the Elk River Railroad. No coal was originating from the former BC&G during this era either.

Dan Robie 1990 |

During my exploration of this area in 1990, it was apparent that track work was done at Glendon within the recent past. The condition of the track and right of way here was significantly better than at other locations and perhaps, the last major maintenance conducted by the Chessie System on this region of railroad during the mid- 1980s.

This section of the 1908 topo map covers the region from the east of Glendon into Gassaway. Frametown is the most notable place name between the two points and is referred to as more widespread than indicated on the map. Aside from Frametown, flag whistle stops dotted this stretch of railroad along the Elk until Gassaway. A "linear" Interstate 79 is added for modern day reference.

Rockton

|

This image is from the I-79 bridge at the Frametown exit and looks west over the railroad at the place location of Rockton. Even with the poor image quality, there is evidence of an old siding here. Not sure if this is what was referred to as Astor Siding or a different one altogether. Dan Robie 1980

|

Frametown

In a region that is recorded as being settled in 1798, the location was first known as Frames Mill until eventually being changed to Frametown in honor of its founder, James Frame, Sr. For a small community, it extends for several miles with various references to Frametown scattered along WV State Route 4. As the Coal and Coke Railway was constructed on the south bank of the Elk River, it was one of two railroads that traversed the community albeit for only a decade. From 1910 to 1918, the narrow-gauge Elk & Little Kanawha River Railroad also passed through town on its trek to the woodlands of Gilmer and Calhoun Counties.

Before....1982

|

After....2013

|

|

A scene with rural country flavor and the house positioned just beyond the railroad right of way. This eastbound view at Frametown is more befitting of North Carolina than West Virginia with the encroachment of kudzu. The shiny rails mean the trains are still moving. Dan Robie 1982

|

Thirty years later the house is still there but the railroad is obviously a far cry from earlier times having been overtaken by weeds. Even with the rural setting, we'd know this image is modern day with the DirecTV dish on the porch roof. Dan Robie 2013

|

Frametown was the last passenger stop moving eastward before arriving at Gassaway lasting into the B&O era. In fact, in terms of freight, the depot (B&O call letter F) was among the final ones to remain active between Charleston and Gassaway existing at least until the late 1950s. There also were also shippers in the region which lasted until the final years of the Chessie System. Today, car storage by the Elk River Railroad occupies the former main line extending west from Gassaway to the vicinity of Frametown.

|

A view looking westbound at Frametown. The area to left of the track looks like where both a siding was and perhaps the location of the depot although I could not confirm this. Dan Robie 2013

|

This is currently the end of the line for the Elk River Railroad (TERRI) at this point in time. The final cut of cars extending west from Gassaway into Frametown occupying the main line. I recall seeing boxcars at this old plant location during the early 1980s. Dan Robie 2013

|

The emerald green splendor of the Elk River at Frametown. If West Virginia is indeed "almost heaven", then the hand of God assuredly graced the beauty of this magnificent stream. Dan Robie 2013

Two views of the Elk River Railroad in operation at Frametown during 2021. This was the westernmost point on the railroad for car storage by the railroad. These may possibly be only a few of the photos in existence of trains at Frametown--from the Coal & Coke Railway era through B&O to the Elk River Railroad. Images courtesy Ian Hapsias

Shadyside

|

A view across the Elk River of the railroad running westbound at Shadyside. A bridge from the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad once crossed here. Dan Robie 2013

|

Shot through a thicket of sycamore trees, the B&O deck bridge across Coon Creek is partially visible. Another 1940s pier replacement is visible. Dan Robie 2013

|

The community of Shadyside was of commercial importance along the Coal and Coke Railway during the early 20th century. A major shipper along the railroad here was the Boggs and Stave Lumber Company which specialized in wood staves. This company operated dedicated trains on the Elk and Little Kanawha Railroad to the timber rich regions of Gilmer and Calhoun Counties from 1910 to 1917.

An Elk River Railroad train returns to Gassaway after moving cars west at Frametown. Location is to the west of Gassaway and this wonderful photograph encapsulates the nostalgia of the railroad here and the lush greenery of West Virginia. Image courtesy of Ian Hapsias

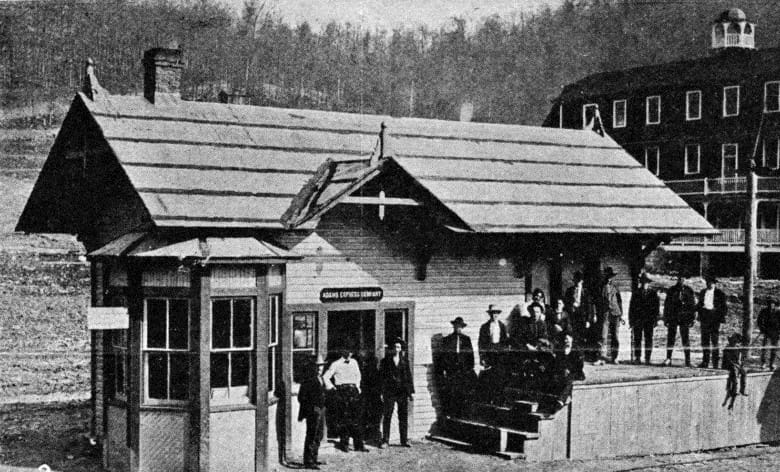

Gassaway

|

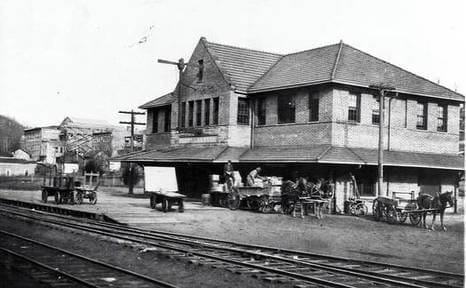

The first railroad depot to serve Gassaway during the Coal and Coke Railway era upon the railroad arrival. Expansion and prosperity resulted in the construction of a larger structure within several years. Image West Virginia and Regional History

|

A very early image of the Gassaway station during the Coal and Coke- B&O transition era. Judging by the horse driven wagons, this undated photo is perhaps circa 1915-1920. Dan Robie collection

|

|

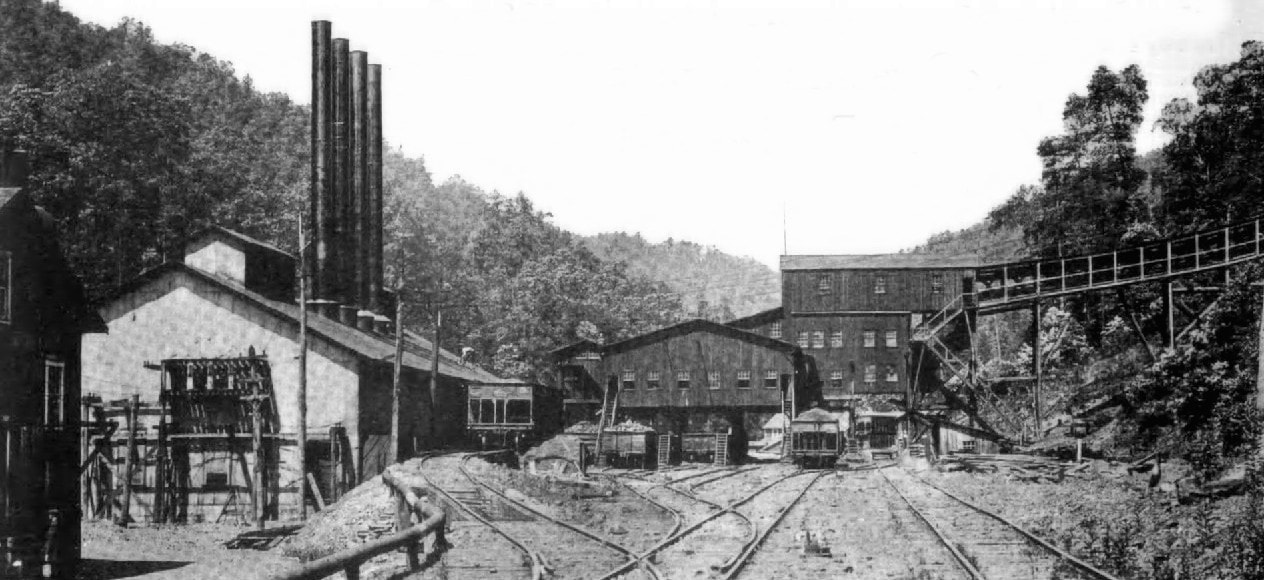

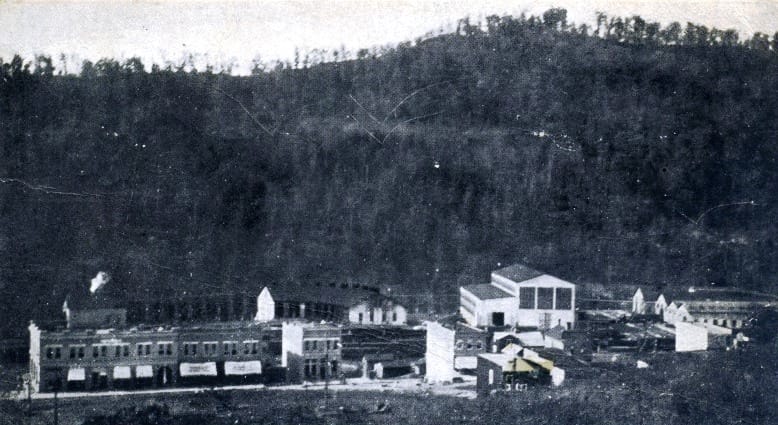

A concentrated view of the Coal and Coke Railway facilities at Gassaway. As the primary yard between Charleston and Elkins, it was complete with shops, turntable, and other servicing amenities. Image West Virginia and Regional History

At right: Railroads were deeply entrenched with community life in bygone years. It was not unusual to find baseball leagues and playing bands such as the B&O Railroad Charleston Division YMCA at Gassaway circa 1920s. Image courtesy Scott Leonard

|

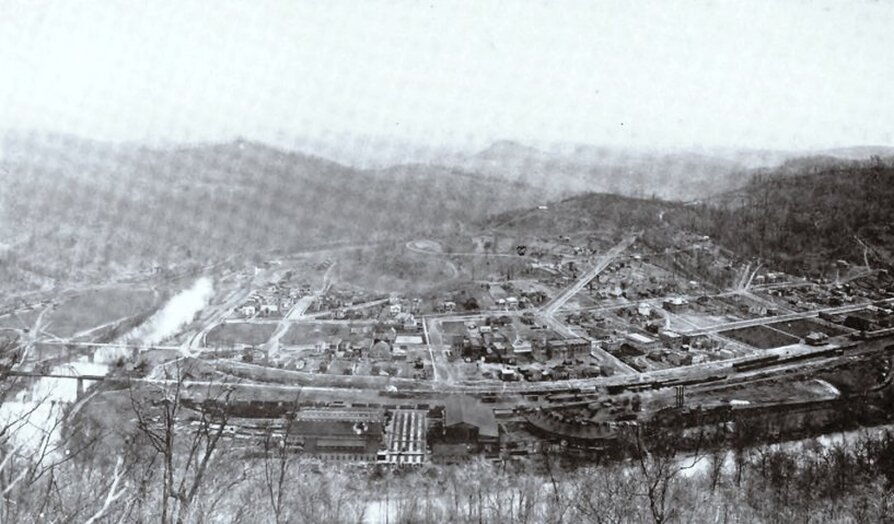

Gassaway at its zenith. The shops of the Coal and Coke Railway dominate the foreground with the yard behind. The railroad is in transition as the B&O is taking control in this circa 1917 photo. This view looks north and the Sutton Branch is visible following the Elk River at left. Image West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey.

The town named after Senator Henry Gassaway Davis, builder of the Coal and Coke Railway, proved to be geographically fortunate for it was virtually at the midway point between Charleston and Elkins. As fate would have it, the Elk valley with its narrow confines, widened here creating a wider plain on its north bank which proved ideal for locating shops and a yard. A railroad buried in the catacombs of West Virginia history, the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad, shared the railroad at Gassaway with the Coal and Coke. This small timber rail route hauled timber, wood staves, and petroleum products for transfer to the Coal and Coke Railway from 1911-1918.

|

Left: Gassaway was still a busy location when this circa 1975 photo was taken. This westbound view reveals coal hoppers that populate the yard and the manifest freight cars indicative of trains still operating to Charleston. At bottom of photo can be seen the Sutton Branch diverging from the main in the east end of the yard. To the right, the plain between the railroad and the Elk River that once contained the Coal and Coke Railway facilities from earlier times. Image Arnout Hyde, Jr. /courtesy of Teresa Hyde.

In later years, this location sufficed for the B&O as the central operations point (B&O call letters GA) between Charleston and Grafton as Gassaway was the staging and termination point for trains to and from Charleston on the Elk River Subdivision. This also meant that it was a crew change point for the continuation of trains in either direction. To either side was a dramatically different railroad--east to Elkins or Grafton, mountainous. West to Charleston, the grade was relatively flat.

Google Earth image of Gassaway looking in the opposite direction from image at left. The wider river plain--and central location-- was an ideal spot for a yard and shops built during the Coal and Coke era on its Charleston-Elkins route. The yellow line traces the route of the former branch to Sutton and cars are visible in the yard stored by the Elk River Railroad.

|

Gassaway Gallery...1970s

If one is an admirer or historian of the Chessie System, Everett N. Young needs no introduction. His photos are well known and have appeared in numerous publications about the Chessie era. I am deeply grateful for his permitting me to share a few period images here.

June 4, 1976: Train #65 with B&O GP40-2 #4107 exits the west yard lead and is underway for Charleston. Those tank cars are likely bound for the Elk Refinery at Falling Rock. Everett N. Young copyright

Gassaway was not unlike any other railroad town in that its economy was directly aligned with the fortunes of the road. The peak years were during the steam era when there were more trains and the affiliated operations that kept steam locomotives maintained. This meant more crews and employees that worked the yards and shops. The winds signaling the beginning of the decline truly began during the 1930s when B&O began to abolish passenger trains not only affecting Gassaway but system wide. By this date, the American highway system was both expanding and improving and it was the trains on the secondary lines that took the initial hit as travelers began the exodus from train to automobile.

There were fluctuations in the coal industry throughout the years due to economic conditions and times of labor unrest. Gassaway was totally dependent of the traffic funneling in and out of its yard from the various branch lines that connected with the Elk River line which generated the carloads. Manifest traffic was more consistent serving the customers from Gassaway to Charleston. But by the mid-20th century, this also began to wane.

There were fluctuations in the coal industry throughout the years due to economic conditions and times of labor unrest. Gassaway was totally dependent of the traffic funneling in and out of its yard from the various branch lines that connected with the Elk River line which generated the carloads. Manifest traffic was more consistent serving the customers from Gassaway to Charleston. But by the mid-20th century, this also began to wane.

|

Vintage B&O and Chessie with four axle EMD power. GP40 #4054 and an unidentifiable sister share the scene with GP30 #6903 that is the background. Everett N. Young copyright 1976

|

A trio of GP9s in this winter shot from 1971. These four axle EMDs were ideal for service on this route. Everett N. Young copyright

|

At the midway point of 1950, there were still four scheduled freight trains that ran between Charleston and Gassaway and two passenger trains. The two passenger trains, #135 and #136, were in twilight and would be abolished within the next year ending all service from Charleston to Gassaway and points beyond. Perhaps the heaviest economic blow to hit Gassaway was during the 1950s when B&O was transitioning from steam to diesel thereby eliminating the servicing facilities and number of crews. This translated into lost jobs that would not be replaced. Gassaway made an attempt to use the former shop buildings to attract another type of business but to no avail. The Gassaway shops were ultimately razed and all were gone by 1961.

|