Ohio River Railroad part i-Wheeling to Vienna

Preface

I did not realize until my teenage years just how intertwined my mother’s life had been to the railroad. Assisting her mother as she did in the post office at Millwood, West Virginia during the late 1930s and early 1940s, she was privy to the daily trains carrying mail and the passengers at the depot. Trains up and down the Ohio River and to the connecting Ripley Branch were a part of life. Still a time of despair on the back end of the Great Depression and the looming clouds of war, the hoboes were steady fare riding the rails seeking a meal from a compassionate heart. They were troubling times yet there was a reaffirming confidence that all would get better.

During the war years, mom became the passenger on the Ohio River line. Sometimes it would be a relatively quick trip to Ravenswood for family business. Other treks would include a longer trip to Wheeling for a weekend visit with Uncle Jim’s family. During the summer months of the World War II years, a trip to Parkersburg for a connecting train over the B&O to Cincinnati to stay with her older married sister. These trips were not necessarily leisure as they also entailed factory work as mom contributed in her role as a “Rosie Riveter”. What was remarkable was that she did this while suffering from polio. The courage and spiritual fulfillment that defined her later life was rooted in her youth.

A half century later in 1990, the family rode an excursion train on the Ohio River line from Huntington to Parkersburg. Mom and dad were awash in nostalgia retracing a route they had not trod since the war years. There had been uncounted changes through the passing decades but reminders of yesteryear remained. The most vivid recollection from mom was when the train pulled into Parkersburg. She began to speak about the Victorian Ann Street station where she had stepped on and off the train so many years before. The station was gone but the memories remained.

Both mom and dad were bonded to the past along the Ohio River railroad but in opposite directions. With mom, it was Millwood north to Wheeling. Dad, on the other hand, was south to Kenova with Millwood as their common denominator. Part two of this piece will include an anecdote about him as a preface.

Both mom and dad were bonded to the past along the Ohio River railroad but in opposite directions. With mom, it was Millwood north to Wheeling. Dad, on the other hand, was south to Kenova with Millwood as their common denominator. Part two of this piece will include an anecdote about him as a preface.

Overview

|

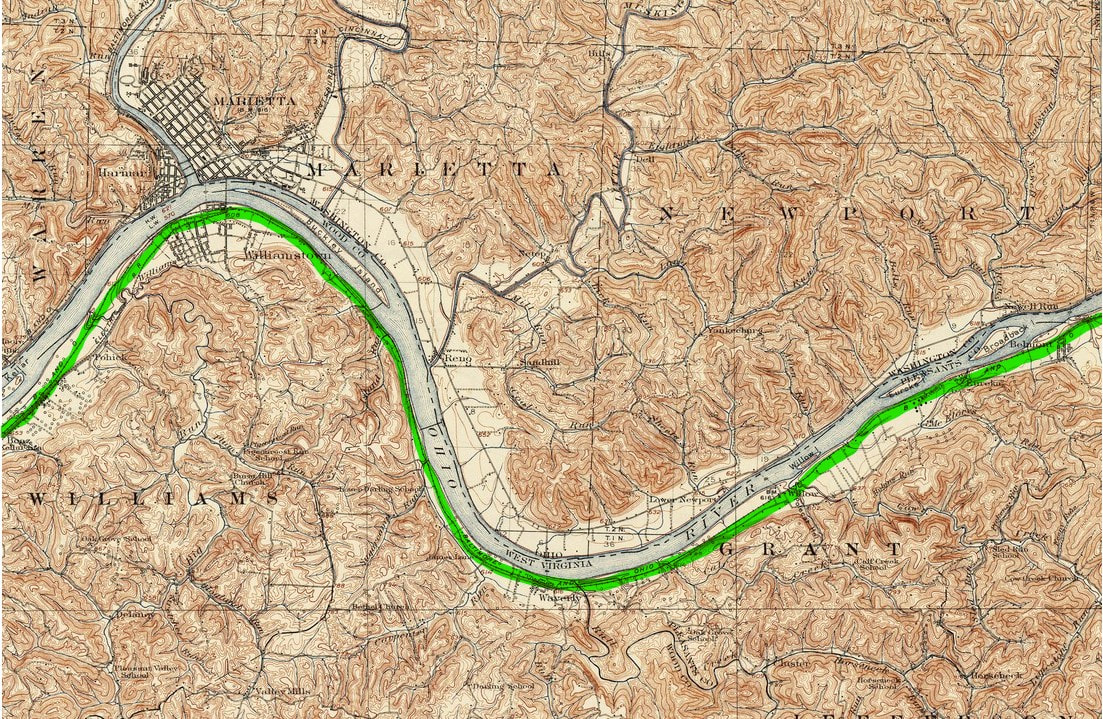

Paralleling the long and winding road that is the Ohio River, the railroad so named for the mighty stream provided a 200 mile long corridor at its bank. Connecting large cities and smaller towns, it became part of the B&O and most of it survives today under CSX.

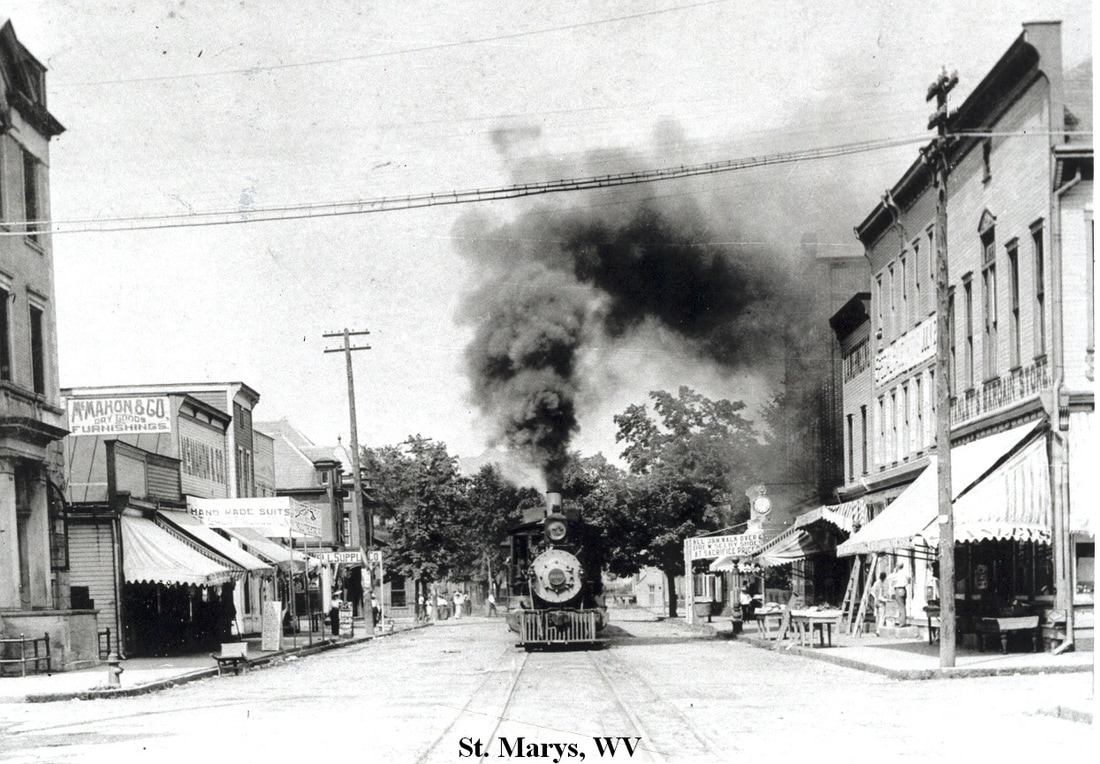

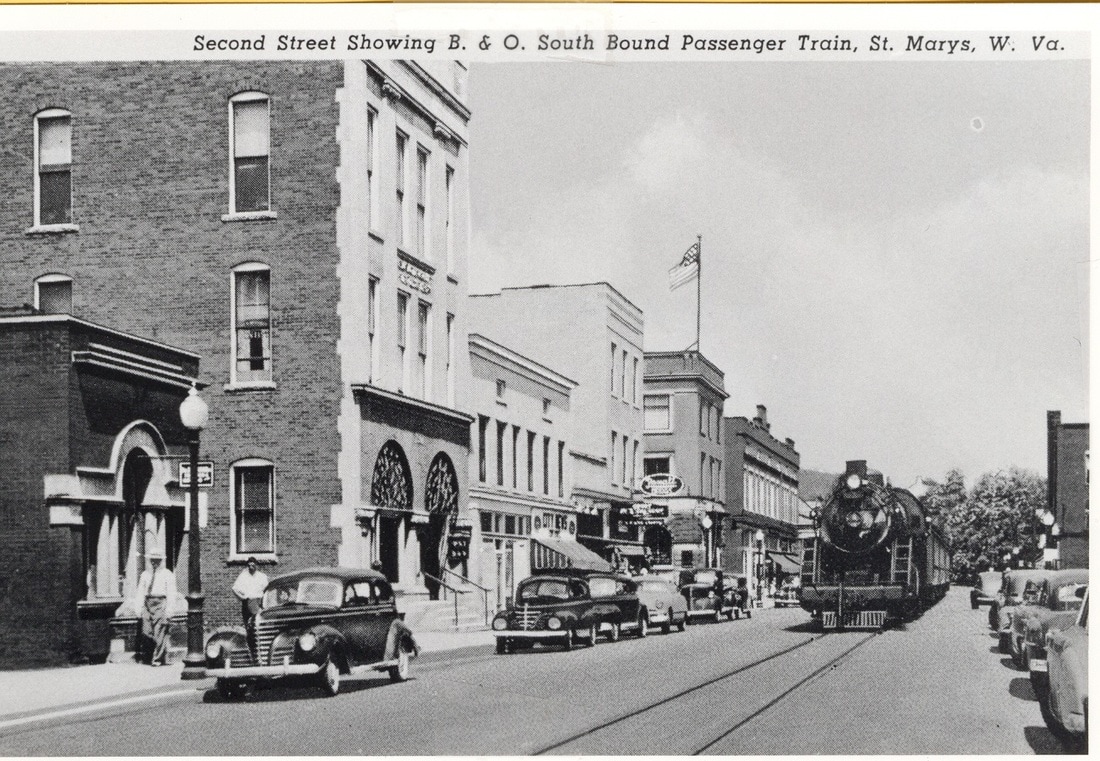

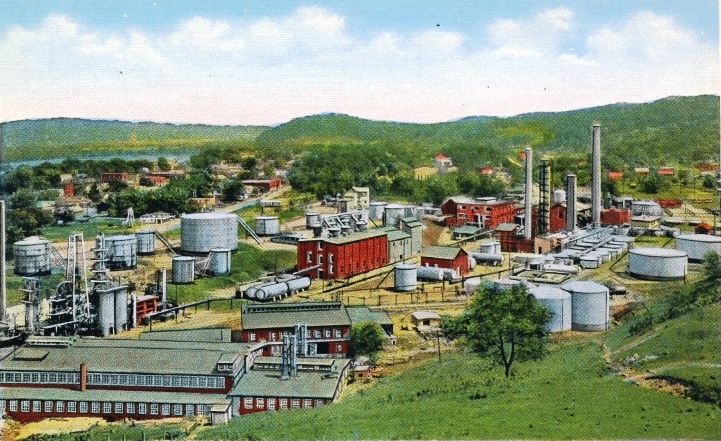

For nearly fifty years, the Ohio River Line presented a dichotomy in regards to its operational demographics. The eastern (geographical north) section of the route developed quicker as industry within the steel belt region located along both it and the Ohio River. By the early 1900s, heavy industry populated the areas of Wheeling, Benwood, and Parkersburg. The smaller communities in between spawned a single primary shipper such as the Quaker State refinery located at St. Marys. In addition, the population was greater in the upper river valley which factored into the volume of rail passengers traveling locally or to make main line connections for a longer journey at either Wheeling or Parkersburg. Other locations provided secondary connections such as the Grafton-Wheeling route (original B&O main) or the Short Line (B&O/CSX) from New Martinsville to Clarksburg. Freight funneled to and from the Ohio River valley via these connections as well. |

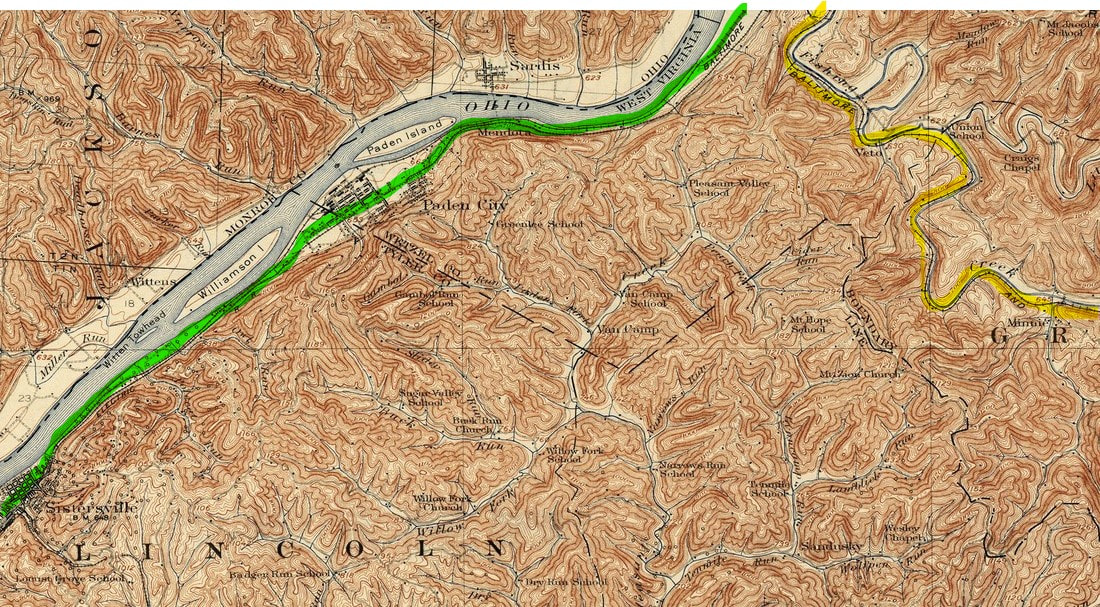

A not to scale map of the Ohio River Railroad and selected locations along the route. The eastern section of the line between Wheeling and Parkersburg was more industrialized and populated. West of Parkersburg to Kenova was predominately rural farmland with smaller communities scattered along the river.

In stark contrast, the railroad west (geographical south) of Parkersburg exemplified a distinctly different persona. Along this stretch of railroad, the only community of size between Parkersburg and Huntington was Point Pleasant. By its sheer rural disposition, shipping along this section was agrarian in nature as the region was dominated by farms populating the bottom lands of the Ohio River. It was not until the post- World War II years that industry began to locate in this region with the notable examples of Kaiser Aluminum at Ravenswood and Goodyear Tire near Point Pleasant. Other lines connected with the Ohio River line between Parkersburg and Huntington—the agrarian feeders RS&G (Spencer Branch) at Ravenswood and R&MCV (Ripley Branch) at Millwood. The third junction occurred at Point Pleasant with a connection to the Kanawha and Michigan Railroad (later New York Central, Penn Central, Conrail, Norfolk Southern, and the present day Kanawha River Railroad). Of these three, only the connection at Point Pleasant remains. At the western terminus of Kenova, the Ohio River line connected with both the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway (C&O) and the Norfolk and Western Railway (N&W). Today, the direct N&W connection is gone and the Ohio River line connects with the C&O (both now CSX) at Guyandotte east of Huntington.

Historical Background

|

The phrase "Ohio River Railroad" actually has a dual meaning with respect to B&O and later history and is often interchanged. In regards to the region between Benwood and Moundsville, it is two distinct entities from the early history as the B&O and Ohio River Railroad were in fact physically separate. It was only after B&O took control of the Ohio River Railroad that the entire route from Wheeling to Kenova paralleling the river was generally referred as such. In reality, however, the B&O between Moundsville and Wheeling was the original main line from Baltimore. During the B&O years, the line was referred as the "Ohio River Division" or the "Ohio River Line". Today under the umbrella of CSX, the route is known as the Ohio River Subdivision.

|

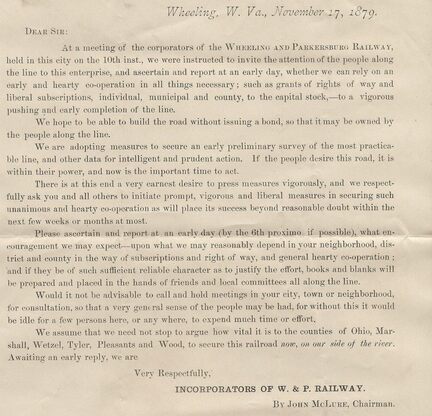

A paper corporation known as the Wheeling and Parkersburg Railway wrote this letter as a lobbying effort in 1879. The central issue at hand was for construction of the railroad on the West Virginia side of the Ohio River. Courtesy Williamstown History Group

History records that the line that would ultimately be constructed as the Ohio River Railroad was initially surveyed for a completely different route. With its proposed origins emanating in Parkersburg, the plans for a railroad were heavily influenced by the moving of the West Virginia state capital between Wheeling and Charleston. This original charter issued in 1880 under the name of the Parkersburg and Charleston Railway Company by prominent Parkersburg citizens--mostly political--chose and surveyed a route from Parkersburg to Charleston by way of the interior of Jackson and Kanawha Counties. Originating in Parkersburg, the survey move south through Mineral Wells, Rockport, Limestone Hill and once entering Jackson County, to Sandyville and Ripley. Continuing south into Kanawha County, the proposed route included Sissonville before reaching Charleston.

Midway through the survey, an alternate route was selected. Once the original survey neared Ripley, instructions were given to move west to Ravenswood and then follow the Ohio River south to Mud Run (Letart) in Mason County whereupon it move across to the Ten-Mile Creek drainage and follow that stream to Leon on the Kanawha River. From this point, it would parallel the river south to Charleston. But once again, the survey plans were changed. New plans were to include moving north from Parkersburg to include Moundsville and Wheeling and the name of the line was changed to the Wheeling, Parkersburg and Charleston Railway although the railroad would never reach Charleston because yet another change transpired. The interior route to Charleston was abandoned altogether and the survey remained in the Ohio Valley with plans to extend south from Parkersburg to Huntington and Kenova. In 1882, the name was changed a third and final time to the aptly titled Ohio River Railroad.

Once the surveys were completed, construction began and by 1884, the railroad was completed between Benwood and Parkersburg. Four years later in 1888, westward expansion from Parkersburg extended the line to Huntington; by 1893, to Kenova. The construction of the Ohio River Railroad was an easier task than the majority of railroads built in West Virginia would be. Contained entirely in the wide plain of the Ohio Valley, its workers had no mountain grades to surmount or tunnels to bore. The greatest challenge confronted was the numerous creek and river bridges that were necessary to complete the railroad. Operationally, it would be at the mercy of the powerful Ohio River--it was susceptible to flooding throughout the years that caused loss of life, destruction, and virtual shutdowns of the railroad. Two catastrophic floods of note occurred in 1913 and 1937 respectively.

|

From the time of its completion in the 1880s until the World War II era, the railroad operated without any dramatic changes. As an operational entity, the Ohio River Railroad was independent for little more than a decade after its completion. B&O began operating the line in 1901 and acquired outright ownership in 1912; hence,the original ORR line between Moundsville and Benwood became secondary used primarily for serving industry. Later, a section of it would be removed in the Benwood Yard area extending to Glendale and today, none of it remains. The Ohio River Railroad was operated as a separate division of the B&O until it was absorbed into the Wheeling Division in 1921.

The industry was primarily concentrated in the Wheeling-Parkersburg region and to the extreme opposite end at Huntington. In between lay a vast fertile Ohio Valley dominated by agriculture with manufacturing scattered within. Passenger traffic was heavy reaching a peak during the World War I years then noticeably declining by the 1930s. Freight trains were frequent pulled by light steam power west of Parkersburg but restricted by the cantilever Kanawha River bridge at Point Pleasant. Once the bridge was replaced with a heavier truss structure in 1947, larger power and longer trains became the norm. |

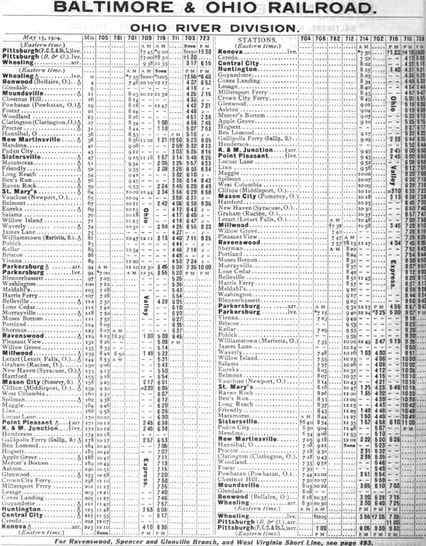

1904 passenger timetable for the Ohio River Division. The line was operated by B&O at this date but not yet outright owned.

|

Transformation along the Ohio River line became noticeable during the late 1940s. The largely agrarian region west of Parkersburg began to attract new postwar industry in the Ravenswood and Point Pleasant areas. Agricultural products and livestock were in decline as primary rail shipments and the construction of power plants introduced regular coal traffic to the line. During the 1960s, reorganization of operating divisions by the B&O led to the abolishment of the Wheeling Division in 1961--the railroad was hence incorporated into the Monongah Division. Passenger trains had ceased on the route by 1960 but B&O was ordered by the West Virginia Public Service Commission to continue providing service on the route. B&O responded by offering ridership in the caboose of freight trains for the few patrons that remained by this date until the advent of Amtrak in 1971. Another significant change occurred in 1963 after the C&O acquired control of the B&O. The original Ohio River Railroad route between Guyandotte and Kenova was abandoned in 1965 as part of a B&O/C&O trackage consolidation through Huntington which resulted in a new connection. The B&O now terminated at a junction with the C&O at Guyandotte. Finally, it was also during the 1960s that the Ohio River route lost its two connecting branch lines in Jackson County--both the Ripley and Spencer Branches were abandoned.

The blue, yellow, and vermillion of the Chessie System burst onto the scene in vivid color during the 1970s but with the B&O still retaining its corporate identity. Operations would remain consistent through the decade but the onset of the 1980s would witness significant changes on the railroad. Although the traffic remained respectable with coal and carloads for industry at Ravenswood, Point Pleasant and Parkersburg areas, the once heavy industrial sector between Wheeling and Parkersburg was in dramatic decline. The loss of manufacturing and petroleum based industry adversely affected the regional economies and the railroad. Throughout its existence, the Ohio River Railroad and B&O had essentially been a Huntington-Wheeling corridor extending to Pittsburgh. By the end of the 1980s, the traffic pattern on the railroad was redefined. In 1985 during the Chessie System to CSX transition, the Parkersburg-Clarksburg segment was closed on the former B&O St. Louis mainline. This precipitated the rerouting of traffic between those two points via the Short Line from Clarksburg and New Martinsville. The Ohio River line was now a section of a roundabout secondary main between Cumberland, MD and Cincinnati. During this same time period, the former B&O route between Wheeling and Pittsburgh was severed abolishing that once long standing service.

The CSX era has been a mixed bag for the river line. Traditional industrial traffic has declined but a respectable number of carloads remain. Coal traffic has also declined with the closing or conversion to natural gas by power plants and the railroad has vanished from Wheeling. However, a positive development in recent years is sand fracking and increased traffic related to that industry particularly in the Northern Panhandle area. CSX has followed suit by increasing capacity to handle the carloads for this newer business. The upper Ohio Valley, to an extent, is witnessing a renaissance of newer industry in line with the 21st century as products related to fuels and recycling are emerging to replace the long gone smokestack industries.

Operationally, the Ohio River Railroad through present day CSX is classified as "dark territory". Train movements were and are governed by train orders and track authorities as the line has been unsignaled but for a few locations. Signal locations existed along the original main line at Benwood and Wheeling and on the Ohio River line itself, terminal locations and/or junctions such as at Moundsville, New Martinsville, Point Pleasant, and Guyandotte.

This piece, although focused on the Ohio River Railroad, will also include description and images of the original B&O main between Wheeling and Moundsville since the two are interrelated. The other connecting routes such as the Wheeling & Pittsburgh ("The Pike"), Central Ohio, and the Cleveland, Lorain, and Wheeling (CL&W) are omitted as are the lines of other railroads in the Wheeling area. Wheeling railroad history is diverse and encompassing on a large scale when all of the railroads that served the area are taken into consideration. Inasmuch, a comprehensive piece could be constructed about Wheeling on its own merit. Another footnote is that images of the B&O diesel and Chessie System era are not commonly available in the public domain. As any are acquired or contributed for use, they will be inserted into the respective location(s).

Motive Power

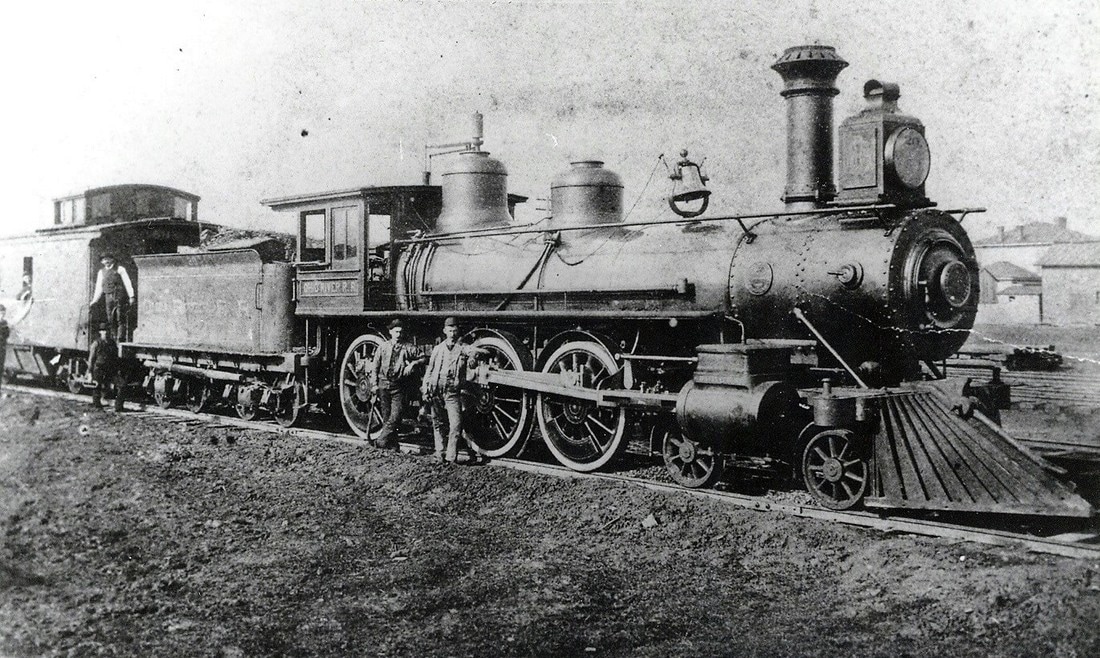

The locomotives of the Ohio River Railroad were of three types—0-6-0 switchers, 4-4-0 Americans, and 4-6-0 Ten-Wheelers. By the time of the B&O takeover, it was considered light power and with certain examples--obsolete power. Below is a list of ORRR locomotives that survived into B&O ownership. These locomotives were relegated to yard or branch line service but all had been scrapped by the Great Depression era.

ORRR 4-6-0 #61 and #62 became B&O class B-28 #275 and #277 (retired by 1926)

ORRR 4-6-0 #100, #102-104 became B&O class B-29 # 278, #280-282 (retired by 1927)

ORRR 4-6-0 #30, #31, #33 became B&O class B-30 # 296, #297, #299 (retired by 1912)

ORRR 4-6-0 # #51 and #52 became B&O class B-31 #300 and #301 (retired by 1924)

ORRR 4-6-0 #27-29 became B&O class B-32 #302-304 (retired by 1924)

ORRR 4-6-0 #26 and #41 became B&O class B-33 #319 and #321 (retired by 1924)

ORRR 0-6-0 #1 and #3 became B&O class D-11 #330 and #332 (retired by 1915)

ORRR 0-6-0 #26 and #41 became B&O class D-14 #305 and #306 (retired by 1934)

ORRR 4-4-0 #2, 4, 10 16, 17, 20, 21 became B&O class G-9 #617, 619, 646, 653, 651,655, 609 (retired by 1912)

ORRR 4-4-0 #11 and #12 became B&O class G-9 #661 and #663 (retired by 1912)

ORRR 4-4-0 #21, #22, and #23 became B&O class G-10 #657, #658, and #627 (no retirement date)

ORRR 4-4-0 #25 became B&O class G-11 #659 (no retirement date)

ORRR 4-6-0 #61 and #62 became B&O class B-28 #275 and #277 (retired by 1926)

ORRR 4-6-0 #100, #102-104 became B&O class B-29 # 278, #280-282 (retired by 1927)

ORRR 4-6-0 #30, #31, #33 became B&O class B-30 # 296, #297, #299 (retired by 1912)

ORRR 4-6-0 # #51 and #52 became B&O class B-31 #300 and #301 (retired by 1924)

ORRR 4-6-0 #27-29 became B&O class B-32 #302-304 (retired by 1924)

ORRR 4-6-0 #26 and #41 became B&O class B-33 #319 and #321 (retired by 1924)

ORRR 0-6-0 #1 and #3 became B&O class D-11 #330 and #332 (retired by 1915)

ORRR 0-6-0 #26 and #41 became B&O class D-14 #305 and #306 (retired by 1934)

ORRR 4-4-0 #2, 4, 10 16, 17, 20, 21 became B&O class G-9 #617, 619, 646, 653, 651,655, 609 (retired by 1912)

ORRR 4-4-0 #11 and #12 became B&O class G-9 #661 and #663 (retired by 1912)

ORRR 4-4-0 #21, #22, and #23 became B&O class G-10 #657, #658, and #627 (no retirement date)

ORRR 4-4-0 #25 became B&O class G-11 #659 (no retirement date)

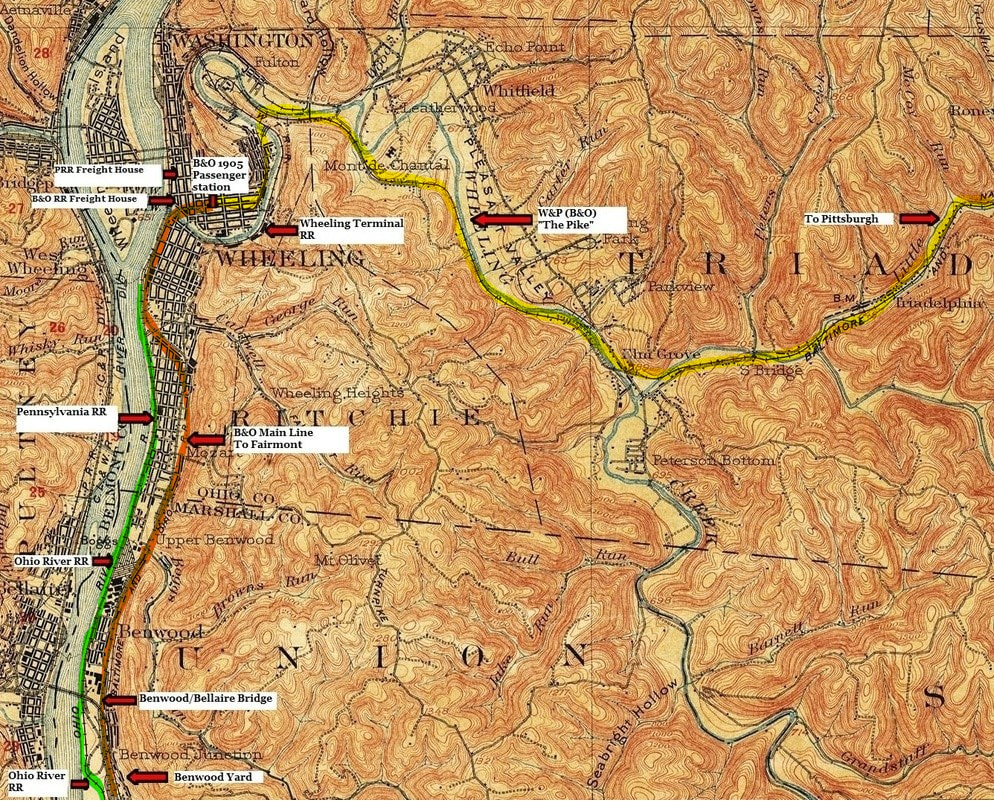

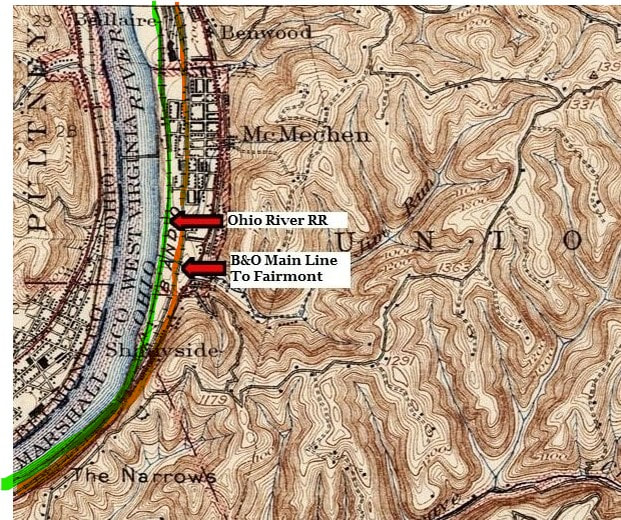

This 1903 topo map highlights the Wheeling and Benwood area near the time of its apex. A tremendous amount of railroad packed into the narrow Ohio River valley featuring the B&O main line (orange), Ohio River Railroad (green), Wheeling Terminal Railroad, B&O Wheeling-Pittsburgh "Pike" (yellow) and the Pennsylvania Railroad. Benwood Yard and the Ohio River bridge connecting the Central Ohio Railroad (B&O) and the Cleveland, Lorain, and Wheeling (CL&W-also B&O) are also included.

Wheeling

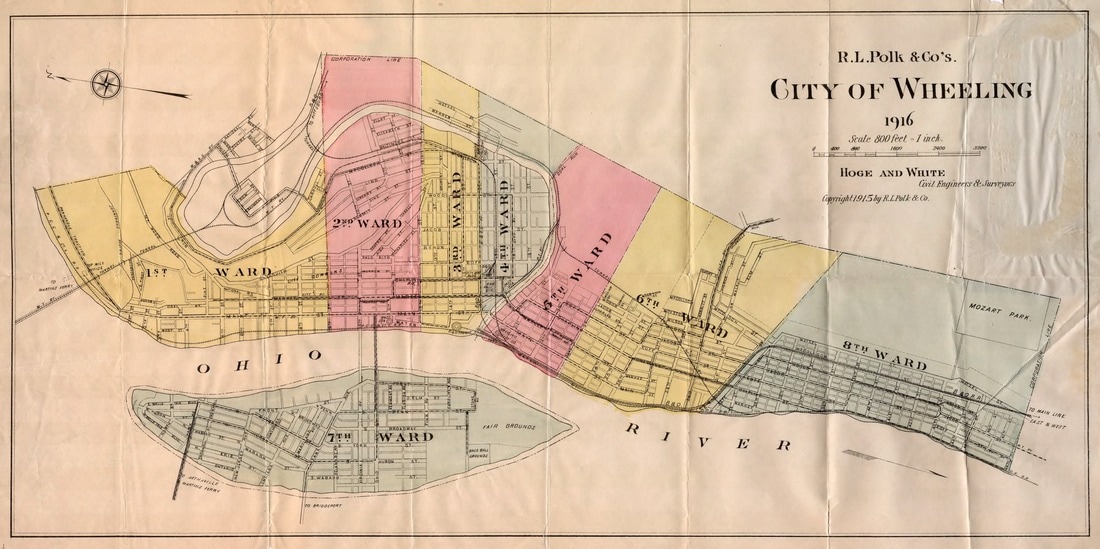

A fascinating map of Wheeling with its political districts as it was in 1916. For the purpose of this page, it provides excellent detail of the railroads inside the city with specific points identified. Map Howard Speidel/Rails and Trails.com

When the construction crews connected the two tracks built from opposite directions Christmas Eve 1852 at Rosbys Rock, VA, the B&O Railroad was now completed from Baltimore to Wheeling. The word “Ohio” in the company name stood legitimized for the railroad now reached the bank of the mighty river so named. Great celebration followed on the heels of this accomplishment as railroad officials and dignitaries from Baltimore boarded the inaugural train to traverse the entire route to Wheeling. The city, also jubilant with the arrival of the railroad, looked forward to a bright future of great prosperity as both a river port and rail center. And prosperity followed accordingly. The fortunes of Wheeling grew not only as a center of the developing manufacturing base but also as the early political power in Western Virginia.

|

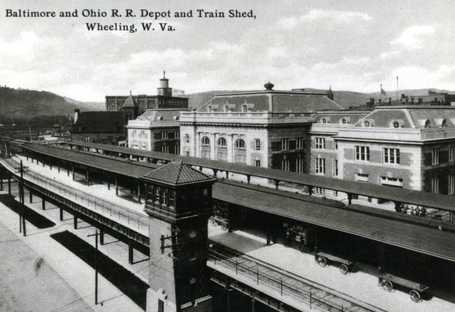

Picture postcard of the Wheeling station during its zenith of the early 1900s. Train sheds on an elevated platform and the majestic block and brick station testify to its grandeur and importance as a passenger terminal. Image West Virginia and Regional History.

|

A farewell from more than a half century ago. Family waves to a departing loved one as a train pulls from the Wheeling station in a scene repeated enumerable times through the passing years. J.J. Young photo/courtesy WV Division of History and Culture

|

Within a decade of the arrival of the B&O at Wheeling, the country was engaged in Civil War and Western Virginia was divided in its loyalties to either the Union or Confederacy. The northern region of Western Virginia and the majority of the Ohio Valley was pro-Union and in 1861, the Wheeling Convention was held that ultimately led to the formation of the new state of West Virginia in 1863. Wheeling served as the first capital from 1863 to 1870 in a series of alternating shifts between it and Charleston. After moving to Charleston in 1870, the seat of government again returned to Wheeling in 1875 and remained until 1885 when it returned permanently to Charleston.

Two classes of B&O 4-6-2 Pacifics are represented here at the Wheeling station during the 1940s waiting to take their respective trains west. On the left is class P-7 #5314 and at right, P-6 #5237. J.J. Young photo/courtesy WV Division of History and Culture

As the Industrial Revolution gained momentum, Wheeling became a manufacturing powerhouse. Steadily aligning itself with the growing steel industry of Pittsburgh, it also became known for the manufacturing of cigars, matches, and nails among many garnering for itself the moniker “Nail City”. It was against this backdrop of established Wheeling history that the fledgling Ohio River Railroad was born in 1882.

As the B&O had already been established in Wheeling for 30 years, it was constructed through the heart of an expanding city. Its first passenger station was constructed at the north bank of Wheeling Creek--in fact, the platform extended over the stream adjacent to the freight house also constructed upon the railroad arrival. By the turn of the century, it was apparent that Wheeling required passenger facilities on a larger scale and a grand terminal was constructed in the heart of downtown in 1905. Business continued to develop along its tracks and by virtue of its early arrival, secured a preeminent position within the city.

|

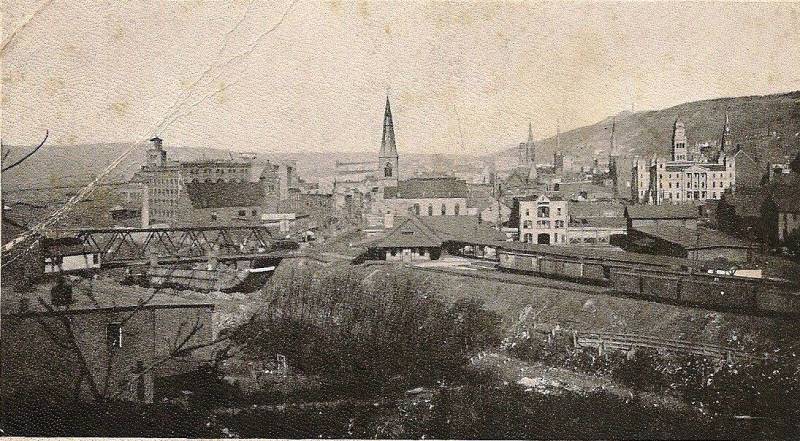

A turn of the century view from 20th Street along Wheeling Creek at the Wheeling Terminal Railroad freight and passenger terminal. Within a few years, B&O would build a grand terminal directly behind the steepled church. Image West Virginia and Regional History

|

A two axle "bobber" caboose of the Ohio River Railroad at Wheeling in 1899. Though "cute" in appearance, it was probably an uncomfortable ride for the crewmen. Image Dan Robie/John G. King collection

|

The Ohio River Railroad was a small player at Wheeling. Dwarfed by the presence of the Baltimore and Ohio and Pennsylvania Railroads, it was in essence a northern terminus of which to interchange freight and passengers with the two giants to and from the Ohio Valley beyond Moundsville. This is certainly the crux of its existence here prior to its 1901 operational takeover by B&O. Once B&O began operating the Ohio River Railroad and certainly after purchasing the line in 1912, the railroad operation was gradually integrated into the B&O network. The trackage rights over the Pennsylvania Railroad between Benwood and Wheeling were ultimately terminated as through freights and passenger trains could directly access the city by the B&O main line between Moundsville and Wheeling. Timetables were created to include direct trains from Huntington (or Kenova) to Pittsburgh via Wheeling. By acquiring the Ohio River Railroad, B&O extended its reach south through the agrarian Ohio River valley to the industrial region of Huntington. As a fringe benefit, it also inherited connections with the Kanawha and Michigan Railroad (later New York Central), Chesapeake and Ohio Railway, and the Norfolk and Western Railway.

With the addition of the Ohio River Railroad, both Wheeling and B&O were nearing their apex. The first three decades of the 1900s marked the pinnacle of Wheeling as an industrial powerhouse and population center. Near the turn of the century, it had the highest per capita income in the United States based on population. The affluence was reflected in the ornate architecture of the city which is still prevalent today. As a river and rail terminal, it prospered from the heavy industry of the region. Wheeling became a major crossroads in the B&O passenger network with lines radiating from the city in all directions. As a result, the B&O passenger station (block operator call letters WR) at Wheeling was the busiest in West Virginia. Into the late 1930s an average of 24 passenger trains arrived at and departed from station daily. By the end of the World War II era, however, changes slowly began to manifest themselves into the harbingers of decline.

As an example of the scheduled war time traffic through Wheeling as listed in a B&O Wheeling Division 1942 timetable, the following are the passenger trains that stopped, originated, or terminated at the 17th Street station:

Eastbound- 1st Class Trains #36, #38, #46, # 58, #72, #78, and #430

Westbound- 1st Class Trains #33, #33, #45, #59, #73, #77, and #431

Four of this group traversed the Ohio River Division: #72, #73, #77, and #78

2nd Class Trains # 81, #82, 102, #104

Trains #81 and #82 operated on the Ohio River Division

Eastbound- 1st Class Trains #36, #38, #46, # 58, #72, #78, and #430

Westbound- 1st Class Trains #33, #33, #45, #59, #73, #77, and #431

Four of this group traversed the Ohio River Division: #72, #73, #77, and #78

2nd Class Trains # 81, #82, 102, #104

Trains #81 and #82 operated on the Ohio River Division

Within the city of Wheeling, B&O utilized the railroad as terminal trackage. It was the area consisting of the original main line from the Ohio River and the Wheeling, Pittsburgh, and Baltimore (W&PB) Railroads moving north from the passenger station that also included the Water Street freight house and 17th Street yard. This sector of the city peaked during the early 1900s but was still bustling with activity in the post war era. A partial listing of shippers still active during this period is as follows: Union Warehouse Holding Company, Quality Tire and Gasoline Company, Philip Carey and Company, Wheeling Storage Company, Wheeling Wholesale Grocery Company, Swift and Company, Keagler Brick Company, OV Distributing Company, Pure Oil Company, and the Union Stockyards.

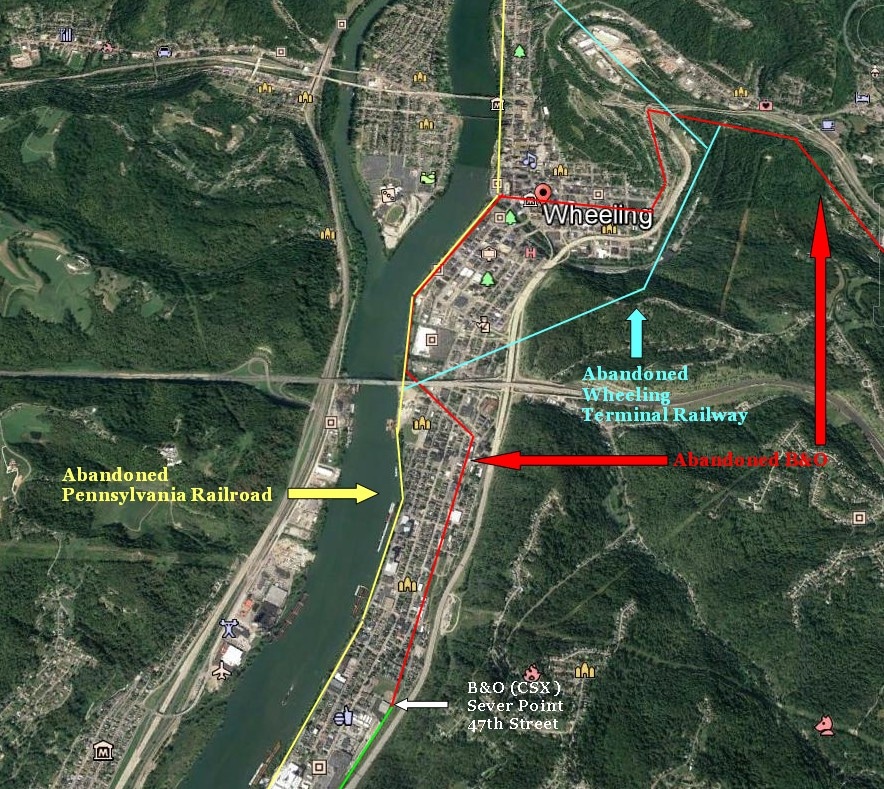

A Google Earth aerial of Wheeling indicating the dramatic loss of the railroad within the city. This once large industrial center and crossroads hub during the passenger train era no longer has any active railroad within its parameters. The red, yellow, and blue lines mark the removed track.

If ever one were to select a microcosm of the rise and decline of industrial America and the effect upon the railroad, Wheeling would suffice as a paramount example. In fact, so dramatic is the change that it can defy the perception of reality because of the scale of railroad activity that existed there.

During the 1950s, the passenger base was quickly eroding at Wheeling--as it was elsewhere--with the preponderance of the automobile, improved highway systems, and emerging air travel. As ridership dwindled, trains were abolished with the transition swift. By the beginning of the 1960s, it was no longer economically feasible for B&O to provide passenger service and in June 1961, the station at Wheeling served its final passengers. Freight operations began to subside with the loss of smaller shippers and the inroads by the trucking industry that was shifting the moving of freight from the rails to the asphalt.

|

Through the 1970s, the evanescence of heavy industry was reflected in the continuing decline of freight traffic. Nowhere was the impact more apparent than in the steel and glass industries as they struggled to survive in an environment ridden with regulations and foreign competition. The decade of the 1980s witnessed massed closings within these long time industries and threatened the existence of the railroads in the area themselves. Northern West Virginia was decimated by route closures beginning in 1974 when the original main line between Fairmont and Wheeling was severed. Though this traffic had been rerouted, this closure was symbolic in that the first railroad to reach Wheeling no longer existed. A decade later, the WP&B---the Wheeling-Pittsburgh line--was closed in November 1985 eliminating through traffic within the city. The track was removed as was the platform at the Wheeling station and the railroad had retreated to the bank of Wheeling Creek. In 2000, CSX filed an application with the Surface Transportation Board (STB) to abandon a nearly two mile section of line from this area south to 47th Street after the City of Wheeling water treatment plant ceased rail service. Shortly thereafter, CSX removed this track closing the chapter of the railroad within the city of Wheeling. Today, only the magnificent Wheeling station--which has housed the West Virginia Northern Community College since 1976--remains as a symbol of the glorious railroad past.

|

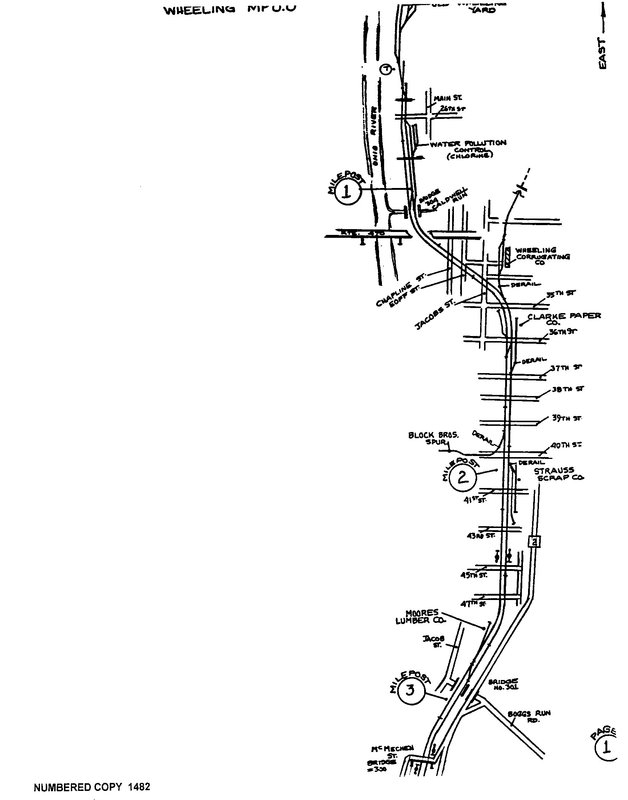

The remnants of the B&O at Wheeling in 1989. Among the final shippers were the Strauss Scrap Company, Clark Paper, Block Brothers, Moores Lumber, and Wheeling Corrugating. The line had been cut to south of Wheeling Creek by this date. By the early 2000s, this section was removed south to 47th Street. Map Bernie Beavers/CSXT.

|

Benwood

Moving west from Benwood Yard and the Ohio River bridge, both the B&O (orange) and Ohio River Railroad (green) were separate but continued to parallel one another. Passing through the community of McMechen, this region was defined by industry and then residential districts adjacent to the railroads.

The north, or railroad eastern, terminus of the Ohio River Railroad was located at Benwood. As a later arrival to the area, it did not gain direct access to Wheeling by virtue of its own rails. B&O was long established having reached Wheeling more than three decades earlier. Directly along the bank of the Ohio River, the Pittsburg(h), Wheeling, and Kentucky Railroad was first built into Wheeling by 1880 and later extended south to Benwood. This railroad was later incorporated as the Pittsburg(h), Cincinnati, Chicago and St.Louis Railroad before ultimately absorbed into the Pennsylvania Railroad network. With both of these accesses to Wheeling occupied by other roads, the Ohio River Railroad was rendered with Benwood as its closest approach. As a result, the Ohio River connected with the PCC&StL (Pennsylvania) at its Benwood yard and utilized its tracks to reach Wheeling. During the fledgling years, the ORR must have either used the PRR or B&O facilities to turn its locomotives. Once the B&O took control of the Ohio River Railroad in 1901, access to Wheeling became a moot point.

The north, or railroad eastern, terminus of the Ohio River Railroad was located at Benwood. As a later arrival to the area, it did not gain direct access to Wheeling by virtue of its own rails. B&O was long established having reached Wheeling more than three decades earlier. Directly along the bank of the Ohio River, the Pittsburg(h), Wheeling, and Kentucky Railroad was first built into Wheeling by 1880 and later extended south to Benwood. This railroad was later incorporated as the Pittsburg(h), Cincinnati, Chicago and St.Louis Railroad before ultimately absorbed into the Pennsylvania Railroad network. With both of these accesses to Wheeling occupied by other roads, the Ohio River Railroad was rendered with Benwood as its closest approach. As a result, the Ohio River connected with the PCC&StL (Pennsylvania) at its Benwood yard and utilized its tracks to reach Wheeling. During the fledgling years, the ORR must have either used the PRR or B&O facilities to turn its locomotives. Once the B&O took control of the Ohio River Railroad in 1901, access to Wheeling became a moot point.

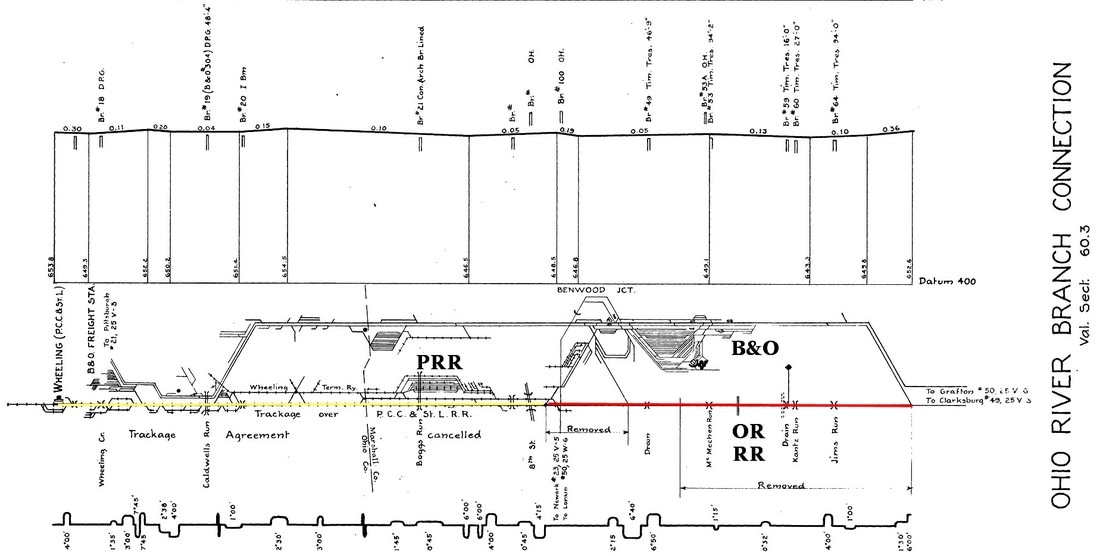

Detailed track map chart of the Benwood-Wheeling layout from 1939. The yellow line indicates the trackage rights used by the Ohio River Railroad over Pennsylvania Railroad tracks to reach Wheeling. Outlined in red is the section of the OR RR abandoned by B&O once it was absorbed into the network. Map Steven Titchenal/Rails and Trails.com

Once the B&O had reached its objective of Wheeling in 1852, the region quickly flourished. Industry steadily appeared utilizing the railroad to reach eastern markets as well a means of passenger travel. The onset of the Civil War tempered rail expansion but in the years that followed, it resumed rapidly. B&O already focused its vision west of the Ohio River with the intent of gaining access to the rapidly developing rail center of Chicago in addition to the Great Lakes region. With these gradual steps of extension, the B&O yard at Benwood would transform into a major hub serving several divisions of the railroad. In fact, it was the center of a spoked wheel of rails lines with near direct access to all major points on the B&O system. Benwood classified freight from the original main line via Grafton, the PW&B to Pittsburgh, the CL&W to the Lake Erie ports, the Central Ohio to Columbus and points west, and the Ohio River line and primarily after absorption into the B&O network. At its peak, it was a marshaling yard for volumes of manifest and coal traffic and replete with all the necessary service and repair facilities.

The aforementioned 1942 B&O Wheeling Division timetable lists the following scheduled freight trains passing, originating from, or terminating at Benwood Yard:

Eastbound: #82, #84, #86, #88, #92, # 96, #98, #810, #970

Westbound: # 83, #85, #87, #89, #91, #95, #99, #281, #961

Of this group, #83, #86, #87, #88, #96, #98, #99 traversed the Ohio River Division

Eastbound: #82, #84, #86, #88, #92, # 96, #98, #810, #970

Westbound: # 83, #85, #87, #89, #91, #95, #99, #281, #961

Of this group, #83, #86, #87, #88, #96, #98, #99 traversed the Ohio River Division

|

A double headed passenger train enters the Benwood bridge loop bound for Newark, Ohio. Soon it will be crossing the bridge in the background. The industrial feel of the area is captured in this World War II era photo. Image John G. King/Dan Robie collection.

|

A passenger train from Ohio exits the Benwood Loop as it hits the diamond on the Benwood bridge lead. The train will crossover to the main as it heads for the Wheeling station. J.J. Young/courtesy West Virginia History and Culture

|

A 1952 description of the Benwood Yard compiled by Gary W. Schlerf for the B&O Historical Society publication “Sentinel” in 1998 listed these statistics: 6 receiving tracks, 10 classification tracks, and a yard capacity of 750 cars that utilized flat switching. An average of 1700 cars was sorted daily along with the dispatching of 78 locomotives. The roundhouse maintained 23 stalls and also at this date, a daily average of 61 trains operating in or from the yard with 19 scheduled freight trains. Adding to this volume of traffic were the scheduled passenger trains still in operation. Block operators at Benwood Junction (call letter N) earned their pay at this extremely busy location around the clock.

No caption is really necessary for this J.J Young classic. A mighty EM-1 2-8-8-4 in Benwood Yard waits to unleash its power in the dark of night in coal service between Fairmont and the Lake Erie ports. J.J Young/courtesy of WV History and Culture.

As did industry and carloads on the railroad, so went Benwood Yard. It was the monitor of the overall health of both. One could say the conversion from steam to diesel power during the 1950s was the waking moment of what lay ahead. As industry subsided, the numbers of cars and trains decreased accordingly. With the abandonments of the connecting railroads during the 1970s and 1980s, the yard declined dramatically in tempo as the need for classification subsided simply due to the rapid loss of volumes. The mid 1980s also marked the closing of the yard shops further reducing its stature. By the 1990s during the early CSX era, the only remaining connections were the Ohio River line and interchange with the Wheeling and Erie (W&LE) which acquired access to Benwood Yard via the Ohio River bridge and the former B&O CL&W route.

|

Houses line the bank above the railroad at Benwood providing residents a view of non-stop action. A westbound passenger train, possibly #73, passes through en route to Parkersburg in this 1940s scene. J.J Young photo/John G. King/Dan Robie collection

|

The Benwood depot as it appeared in later years. A photo that perhaps dates from the early 1960s. Image West Virginia and Regional History.

|

|

The smoky environs of Wheeling Steel at Benwood in 1928. This view is across the river from Bellaire, OH and freezes in time Benwood at its industrial zenith. Image West Virginia and Regional History

|

Complementing the vast facilities at Benwood was the presence of heavy industry that depended on the railroad. During the first half of the 20th century, two coal mines operated at here--the Benwood Mine and the Hitchman Coal and Coke Mine. Tragically, both of these mines were the sites of disasters with the Wheeling Steel owned Benwood Mine suffering the third worst mining catastrophe in West Virginia history. On April 28, 1924, explosions at this mine took the lives of 119 workers. Eighteen years later on May 18, 1942, five workers perished in an accident at the Hitchman Mine.

|

The foremost business here, the Wheeling Steel Company, was founded in 1920. For more than 60 years, its Benwood Pipe mill employed multitudes of workers in addition to generating traffic volumes for the railroad. The company through a merger became Wheeling-Pittsburgh Steel and by the late 1970s, was struggling to survive against a depressed market and foreign competition. It ultimately ceased operation in 1984 and in effect became the symbol of industrial decline in the region.

A Google Earth view of the layout at Benwood. The original Ohio River Railroad ran parallel to the river bank passing the loop and the yard with the B&O main farther away. A unique feature here was the loop itself--this enabled trains to and from Wheeling to access the Ohio River bridge and the two diverging lines in Ohio (Central Ohio and CL&W). Little remains here today of a location that was once a cauldron of railroad activity.

The Benwood Yard of today is but a shadow of its former glory. Its facilities are closed or razed and areas of the yard are forlorn in appearance from disuse. Its main purpose today is to serve as an interchange point with the reincarnated Wheeling and Lake Erie Railway for coal loads coming from and going to Ohio. It is the W&LE--not CSX--that uses the magnificent Benwood-Bellaire bridge that once flourished with B&O traffic. Once a primary yard at a crossroads location of the B&O system, Benwood is now relegated to an outpost on the northern end of the Ohio River Subdivision. This once great railroad area is not completely dead, however. Two businesses--JLE Industries which utilizes a remnant of the Wheeling Steel complex--and Unimin Energy--which developed a fracking facility within Benwood Yard---generate rail traffic. There are actually more railcars in the yard today than there has been in the past three decades. The outlook here is positive with respect to increasing business.

Two examples of excellent B&O steam power in the twilight of their careers at Benwood. At left, a gallant P7e Pacific in stand by service. The glory days of prime passenger power have faded but she still glistens in a coat of Royal Blue enamel. A right, a fabled EM-1 2-8-8-4 now renumbered to #676, runs out its final days in coal service to the Lake Erie ports. Both images Dan Robie collection

For the historian researching past glory, there is solace through the camera work of the late great J. J. Young. He recorded for posterity a volume of photographs from the Wheeling-Benwood-Bellaire, OH region capturing the area in its near prime. It is a privilege to share several of his efforts on this page.

|

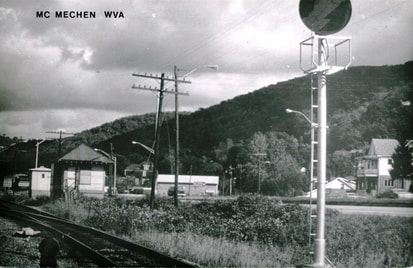

A view looking east through McMechan. The signal is at the west end of the Benwood Yard leads. Image West Virginia and Regional History

|

The Ohio River Railroad began construction at Benwood in 1883 beside its namesake stream at the south end of the Pittsburg(h), Cincinnati, Chicago, and St. Louis Railroad (PCC&StL--later Pennsylvania Railroad) with the objective of first reaching Parkersburg. Its line paralleled the river and ran directly behind the B&O facilities passing by the bridge loop trackage as it moved southward (railroad west). Continuing west, the Ohio River Railroad and the B&O main line ran parallel but separated as they passed through the community of McMechan. Eventually, the ORRR met the B&O main at Glendale and the two ran adjacent.

|

Immediately south of Benwood is the community of McMechen which was laid out in plats during 1888 for a residential area to house the workers at the Benwood industries. Incorporated in 1895, it remained predominately free of any major industry opting to remain a residential town of small businesses and stores. During its earlier years, McMechen was the location of orchards and a stockyard and a notable firm, J.L McMechen---which constructed the B&O roundhouse at Benwood. The west end of the Benwood Yard lead is located at the northern edge of town. Once the Ohio River Railroad was removed from Benwood west through McMechan, a connection was established east of Glendale from the B&O main for the remaining piece of ORRR track west to Moundsville. It appears that this section was used as industrial and storage track.

The region west of McMechen through Glendale to Moundsville is recorded in B&O history as a region of "friendly" passenger train races that occurred between the B&O and the Ohio River Railroad. This was in the earliest years when the ORRR was a separate entity and perhaps this lasted into the early years of B&O ownership. The tracks of both ran parallel for several miles through here which obviously enticed the engineers of both roads. B&O recorded Glendale as a small town of commercial importance to the railroad during the late 1940s. It listed the Glendale Distillery and Marx Toy Factory as active shippers. Today, the right of way of the Ohio River Railroad between Glendale and Moundsville that once served them exists as the Glendale-Moundsville Rail Trail. CSX presently serves the Warren Distribution company here with carloads on a single siding.

Moundsville

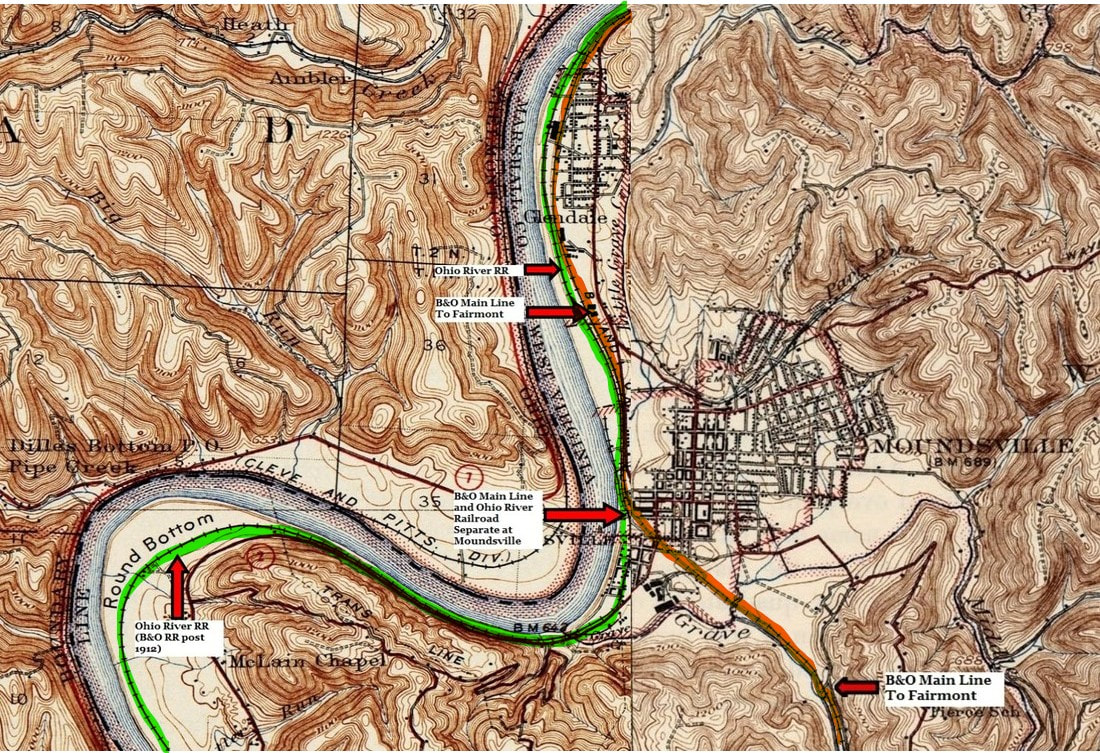

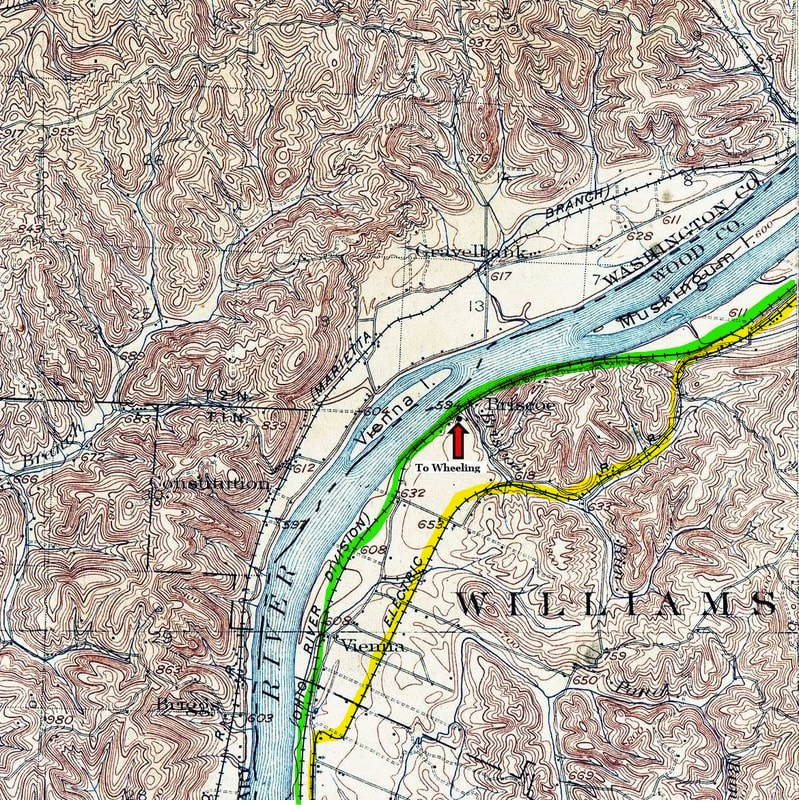

A 1903 topo map of Moundsville and the surrounding area. Moving south (rail west) it was here that the Ohio River Railroad (green) and the original B&O main line (orange) diverged. The Ohio River Railroad continued west paralleling the river whereas the B&O turned east along Grave Creek heading for Fairmont and Grafton.

As the builders of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad moved west along the Ohio River from Wheeling in 1852, they eventually reached the town of Moundsville at the mouth of Grave Creek. Originally named Elizabethtown, the community was incorporated in 1830. At this date, it was a river town but within two decades, the sounds of railroad construction could be heard as a line was under construction extending the B&O from Grafton to Wheeling. When the construction gangs entered Moundsville, they could look west along the river and see there was no other railroad paralleling the Ohio on its journey south and west. Nor would this line follow that course for it was here that the railroad departed the bank of the Ohio instead paralleling Grave Creek and heading for a date with history at Rosbys Rock on December 24. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad would achieve its initial goal at Rosbys Rock as crews met there driving the final spike on a completed railroad extending from Baltimore to the Ohio River. In contrast, that long expanse of land paralleling the Ohio River south from Moundsville to Parkersburg and beyond would remain untouched by the iron horse for another 30 years.

|

B&O 4-6-0 #1343 pauses for a passenger stop at Moundsville during the late 1930s. The train is unidentified but the Ten-Wheeler for power is a telltale for an Ohio River line train. Image John G. King/Dan Robie collection

|

The Moundsville station in its heyday circa 1920s. An active passenger stop serving both the B&O Grafton-Wheeling main and the Ohio River Railroad. Image John G. King/Dan Robie collection

|

|

An advertisement listing the Alexander Mine and its methods of transport. Image Chris DellaMea collection

B&O assigned the call letters MO to the Moundsville depot and telegraph station but no servicing facilities were located here. Two major customers that existed at Moundsville served from the Ohio River line were the Alexander Mine and Fostoria Glass. With a spur from original Ohio River Railroad trackage just north of the Moundsville depot, the Alexander Mine was a large river and rail operation. It operated during the mid-1900s but vanished by the 1980s. No visible traces remain except for the barge moorings which still stand in the Ohio River.

|

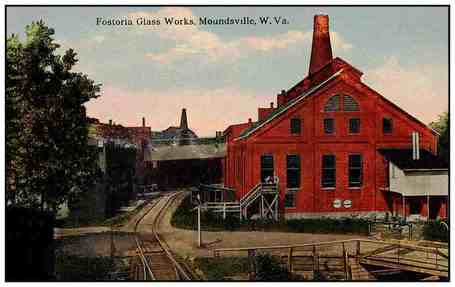

The Fostoria Glass Company as it appeared circa 1915. World famous for its exquisite glassware, its products were purchased by citizens and Presidents alike for nearly 100 years. Its glassware can be found today in the everyday house as well as the White House.

|

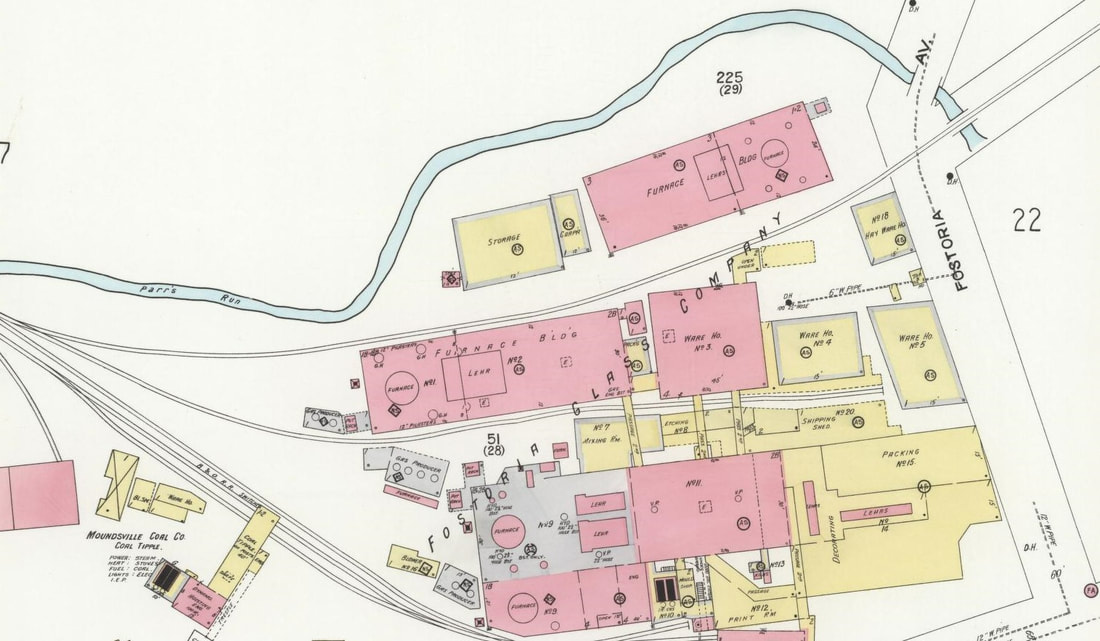

The two largest shippers on the Moundsville industrial track were Fostoria Glass (left) and the US Stamping Plant (right) as they were in 1923. These businesses generated carloads for the B&O for many years with Fostoria Glass remaining active deep into the 20th century.

By the 1920s, B&O had built what would be known today as an industrial park spur. This track branched off the main at the north end of town and served multiple industries such as the aforementioned Fostoria Glass. Other industries located along this line included Mineral State Coal Company, Moundsville Coal Company, US Stamping Company, Moundsville Crystal Ice Company, and the Suburban Brick Company.

Train #343 swings around the curve on the old B&O main from Grafton in 1956. A few folks are gathered either to watch or wait for the arrival of a loved one. The significance of this J.J. Young photo is trifold: P7 Pacific #5300 is the power this day for #343 which is recorded as the locomotive on the final run of this train in 1956. Also, the #5300 is preserved on static display at the B&O Museum in Baltimore and, finally, this scene provides an excellent look at the track configuration here. John G. King/Dan Robie collection

The Fostoria Glass Company was renowned throughout the world for its fine quality glassware. It began operation at Moundsville in 1891 and remained for nearly a century until 1983. A long siding from the Ohio River line was built across the north side of town to serve the plant. For years, the complex stood in ruins until recently demolished. B&O also listed the West Virginia Farm Bureau Co-Op as a shipper in 1948. In recent years, 84 Lumber has been served with a rail siding within the Moundsville city limits.

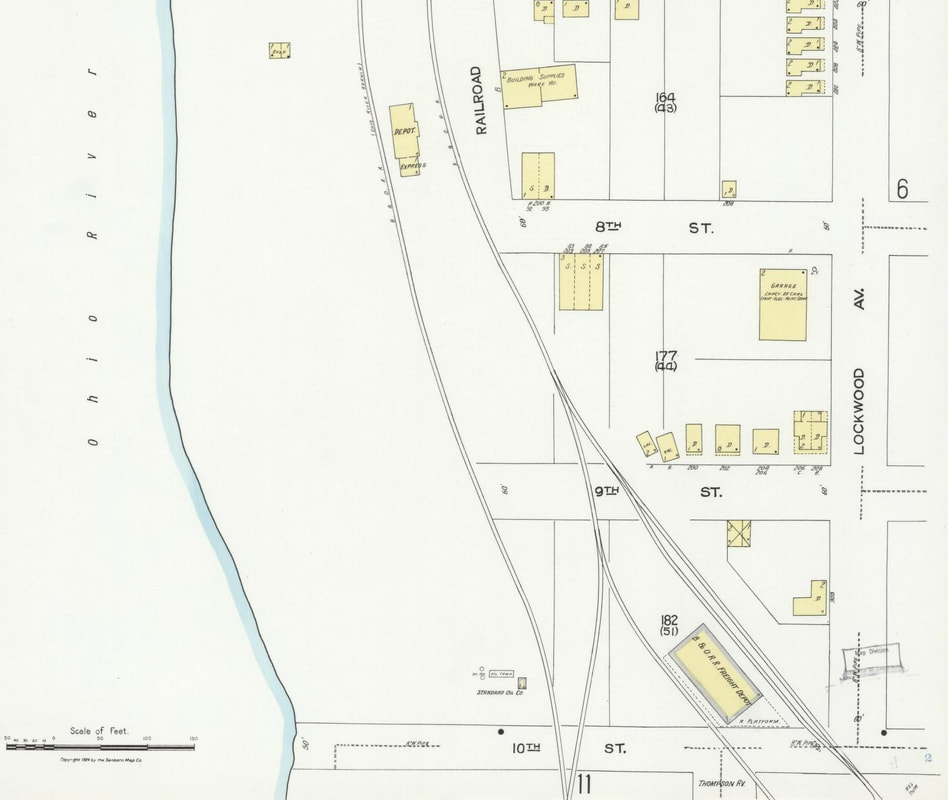

The railroad hub within Moundsville as recorded 1923. The Ohio River line and the B&O main are still in their original configurations at this date. Note the separate depots and the connecting tracks still in use even though the Ohio River Railroad line was now B&O.

|

The Moundsville depot during the 1960s. Time and disuse have taken over creating a rundown appearance. Note that the auxiliary track on the Grafton-Wheeling main has been removed by this date. John G. King/Dan Robie collection

|

Hollywood came to Moundsville in 1970 for the filming of the movie "Fool's Parade" starring James Stewart, George Kennedy, Anne Baxter and others. The Moundsville depot was renamed "Glory" for the making of the film. John G. King/Dan Robie collection

|

By the onset of the 1960s, operational changes began to alter the dynamics at and through Moundsville and in particular, the B&O Grafton-Wheeling main line. Passenger service ceased on the route in 1956 and by the early 1960s, B&O began rerouting freight traffic from Grafton over the Short Line via New Martinsville to Wheeling. The Grafton-Wheeling main was a rugged piece of railroad with grades and twisting curves especially between Mannington and Moundsville. The route was left intact to serve local originating traffic but by the next decade, this had evaporated or was no longer profitable to operate. In 1974, B&O severed its original Baltimore to Wheeling main line--intact for 122 years--when it removed a section of the line between Moundsville and Littleton (Board Tree Tunnel). Effectively, Moundsville was no longer a junction and the original B&O main from Moundsville to Wheeling was melded operationally into the Ohio River Division. As a final swan song to the transformation, the Moundsville depot was demolished in 1980.

A Google Earth view of the former junction area at Moundsville. The yellow lines indicate the original Ohio River Railroad moving east as it paralleled the B&O main to Wheeling. Moving across through town is the right of way of the B&O main towards Fairmont and Grafton. The track between the two lines was the connection between the B&O and ORRR. All that remains today is the single track line fused from both as the CSX Ohio River Subdivision.

If one takes into account the rapid expansion of the railroad system that occurred during the late 19th century, it may appear implausible that a line had not yet been constructed along the Ohio River between Moundsville and Kenova by 1880. River valleys were prime real estate to build because (1) the line could follow the contour of the stream with comparatively easy gradients and few--if any-- tunnels and (2) population centers were located along them. Yet the nearly 200 mile distance from Moundsville south--a length resulting from river bends--was predominately rural farm land punctuated by population centers at Parkersburg and Huntington. Such a railroad would rely heavily on agriculture, developing industry, and a healthy passenger ridership. These were the prospects faced by the Ohio River Railroad in 1883 as it began to lay rail west of Moundsville. No longer in parallel with the B&O, it could claim the remainder of the valley its own. In the context of this article as we continue moving south (railroad west), this 200 mile stretch of railroad taken into ownership by B&O in 1912 and still in existence as the CSX Ohio River Subdivision is wholly the original Ohio River Railroad.

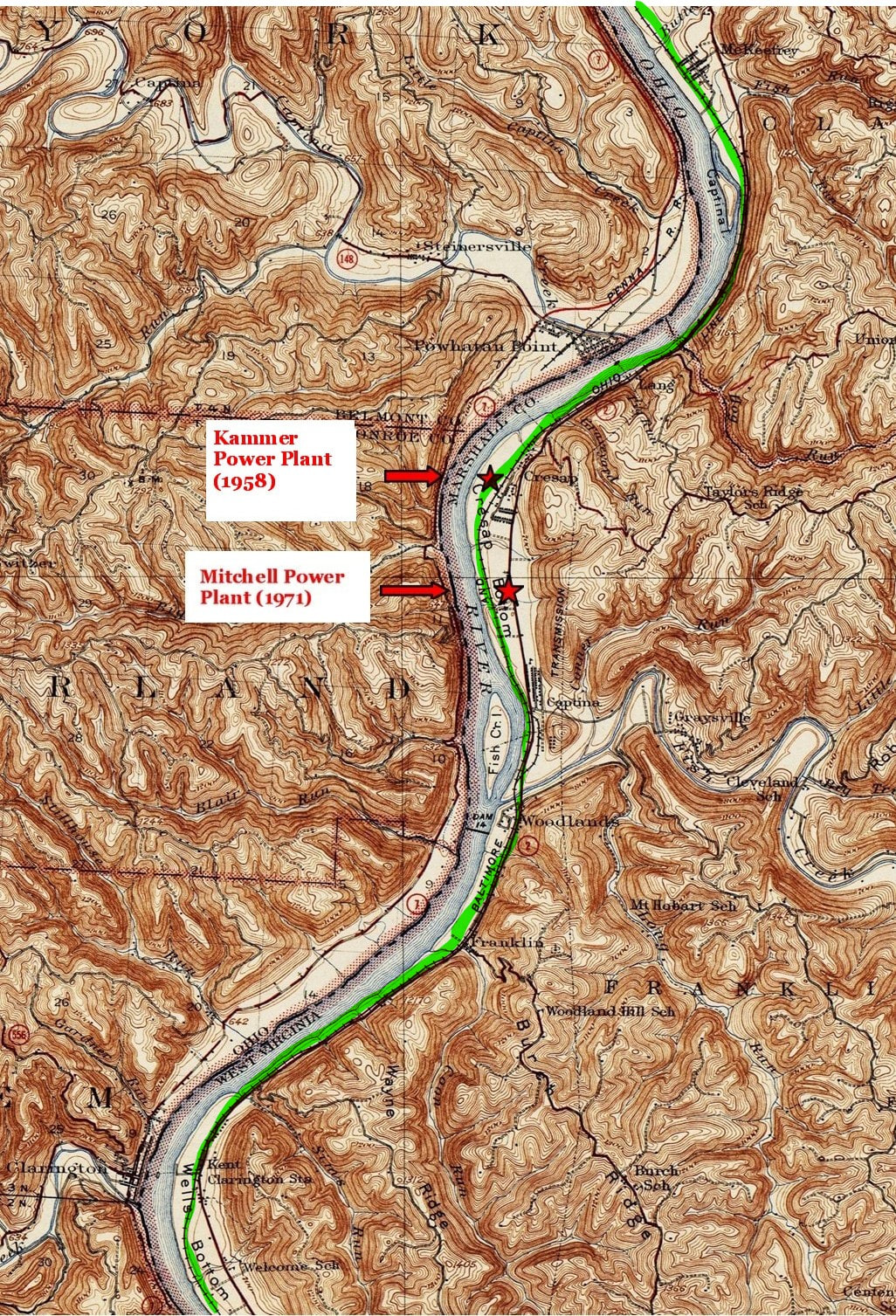

The region south of Moundsville highlighted by three large river bottoms formed from bends in the Ohio River--Round, Cresap, and Wells. Populated by small towns and later industrial development beneficial to the railroad from earliest years to present day.

The region south (railroad west) of Moundsville is highlighted by bends in the Ohio River that created expansive bottom lands. First is the region known as Round Bottom which received its name from the crescent shaped bend of the river. During the early 1920s, a coal company village was established here with an active mine that remained until after the World War II era by the name of McKeffrey. B&O listed a spur that served this mine and location in addition to a 5700 foot passing siding at Chestnut Hill. During the late 1940s, the Glenmont Nursery Company also received rail service. A contemporary shipper located here for CSX is Williams Energy which generates a considerable amount of carloads for the railroad.

Several miles south of McKeefrey, the Ohio River Railroad entered the domain of Cresap Bottom and the first place name here was the whistle stop of Bakers Station. Another wide expanse of bottom land, this region also attracted early settlement dating to the Colonial period and experienced redevelopment extending into the modern era. The first of the small coal communities, Captina, was located at the mouth of Hog Run. A note is in order here due to this place name as there are two locations identified as such in two eras. The one here appears to be a previous one for Lang or it is a map error.

The ORRR constructed a depot here at the tiny hamlet of Lang which was located at the south end of Pig Run. Although there was local patronage here, its primary function was to serve the town of Powhatan Point, OH. Ferry service operated across the river and the depot was often referred as Powhatan Point. Another coal company village located in the bottom is the community of Cresap. This operation was established in 1923 with an operating mine and remained in existence for little more than thirty years. A riverboat location---with a railroad water stop and block station (FO)-- known as Fosters Landing was near here and a 5900 foot passing siding constructed by the ORRR remained in use into the B&O years. Another whistle stop location for the railroad here was about a half mile north of the mouth of Fish Creek known as Whittaker Station. At the south end of Cresap bottom was located the second community named Captina (by the 1930s) It was established in 1919 and was home to the Woodland Coal Company.

Beginning in the decade of the 1950s, Cresaps Bottom underwent significant change. This bottom land was selected for the site of what would be two electric power plants. Construction began on the Kammer plant in 1955 and it was operational by 1958. A decade later, the area south of Hammler was transformed by the second power plant, Mitchell, and by 1971, it was operational. The construction of both plants removed the traces of the communities located there previously. Both utilized river and rail transport for coal. The Kammer plant has recently been decommissioned but Mitchell remains active as of this writing. Another company of the modern era to establish here is the CertainTeed Gypsum plant located on the north bank of Fish Creek.

|

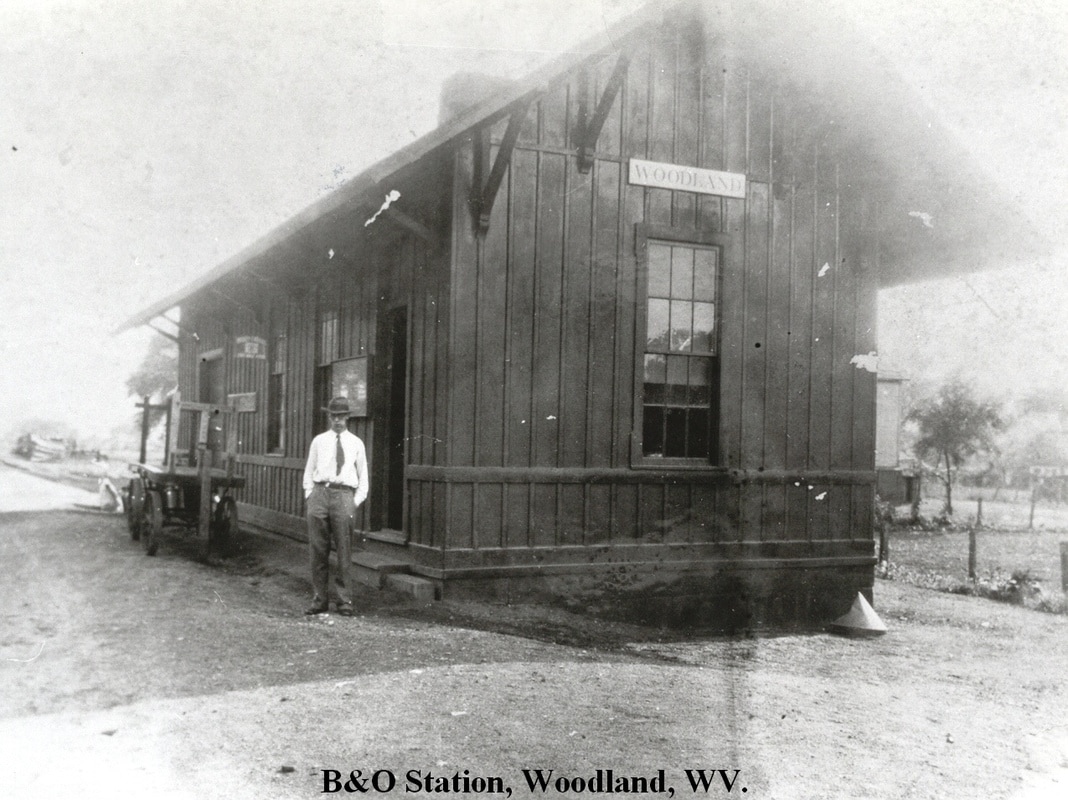

Located on the south bank of Fish Creek at its mouth is the village of Woodland. A railroad depot was located here and the community was the “commercial” district for Captina and the Cresap Bottom area. Scant little remains of this community as the residential district was vanishing during the 1950s and highway construction in conjunction with power plant construction wiped out the business district. Immediately south of here was a whistle stop located at the mouth of Coon Run named Franklin. Modern times included Columbian Chemicals as a shipper.

At right: The Woodland depot as it was circa 1920. This was a busy small town depot for B&O during the early 1900s. Image John G. King/Dan Robie collection

|

|

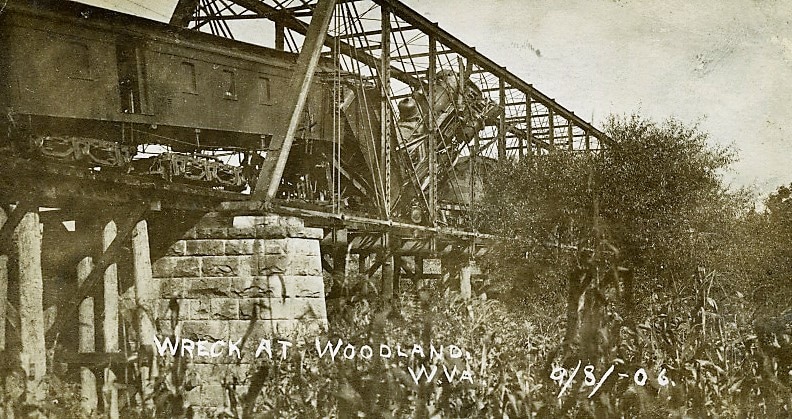

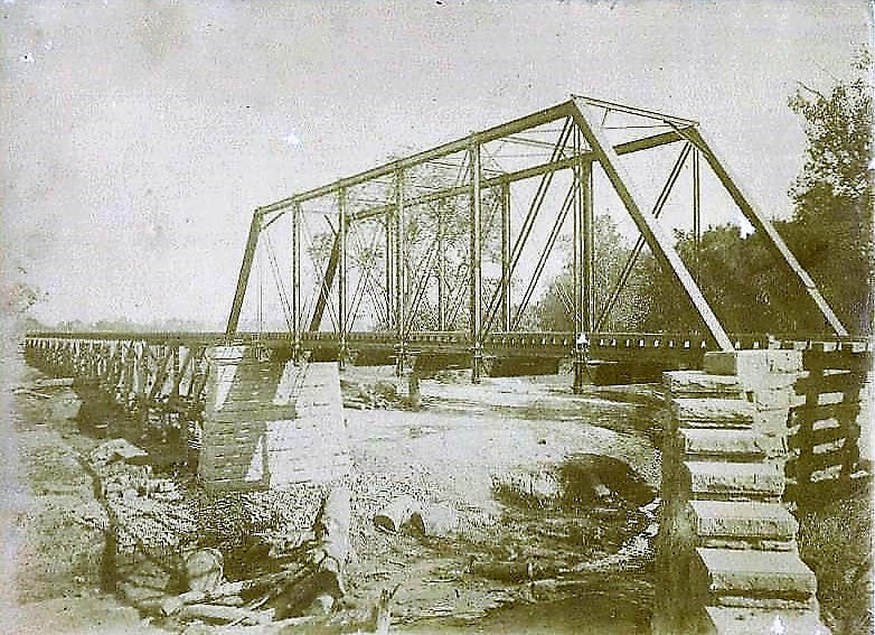

A head on collision that occurred on the Fish Creek bridge at Woodland in 1906. Railroad was still the Ohio River Railroad at this date but operated by B&O. Image West Virginia and Regional History

|

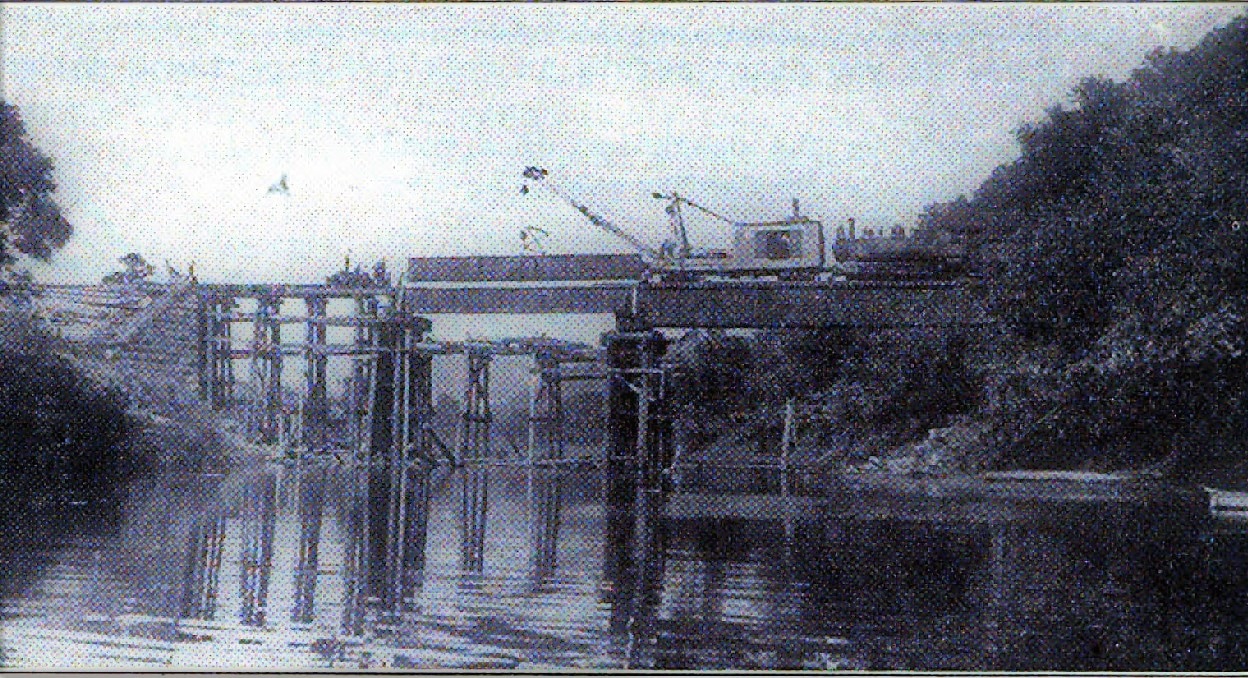

B&O replaced the truss span with a girder plate span at Fish Creek in 1913. High water from the creek had shifted and damaged the bridge. Image B&O Magazine Archives

|

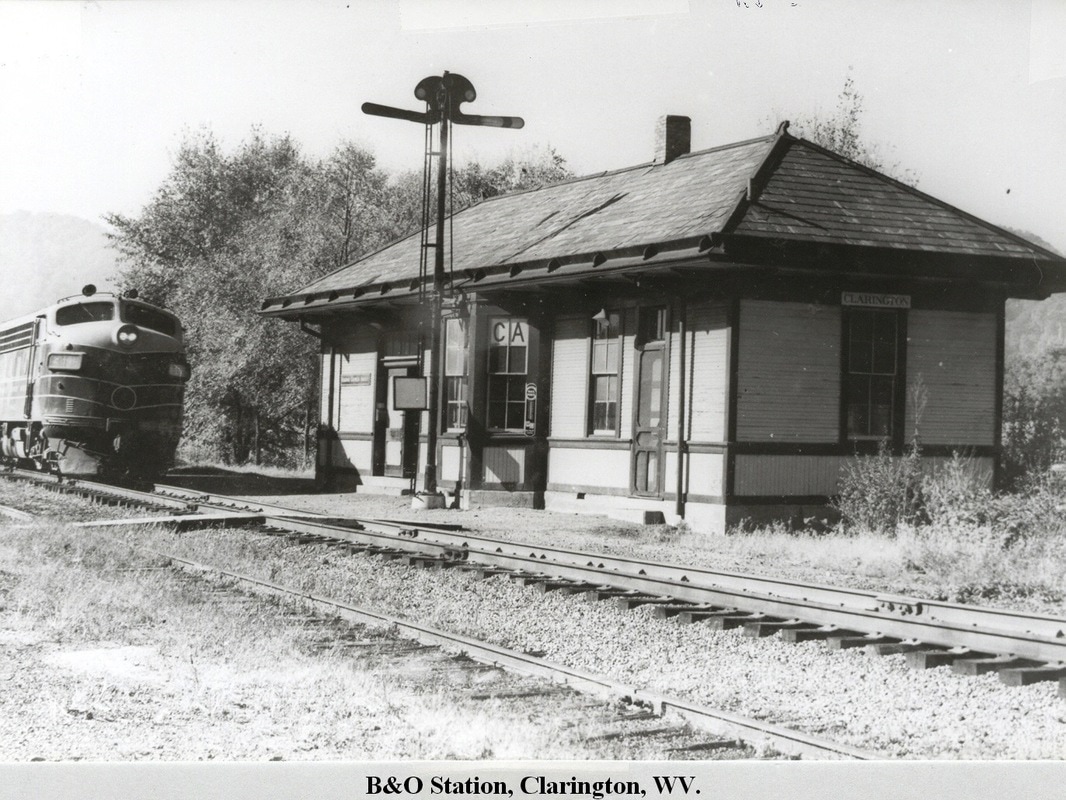

West of Franklin, the railroad entered the Wells Bottom region and the village of Kent which was founded in 1924. Prior to this time, the depot here was named for the township on the Ohio side of the river---Clarington--- of which it served. This location also maintained a coaling station and livestock pen for the B&O in addition to a telegraph station with call letters CB. A ferry service operated between the two points until a bridge was constructed across the river to the south in New Martinsville during the 1960s. A few miles south of Clarington was another flag stop on the railroad at Welcome.

|

Clarington depot during the Depression year of 1933. This depot not only served the Wells Bottom region but also Clarington, OH via ferry. John G. King/Dan Robie collection

|

The passenger trains were gone when this early 1960s photo was taken of the Clarington depot. Still in decent condition but appears altered from its 1933 appearance. John G. King/Dan Robie collection

|

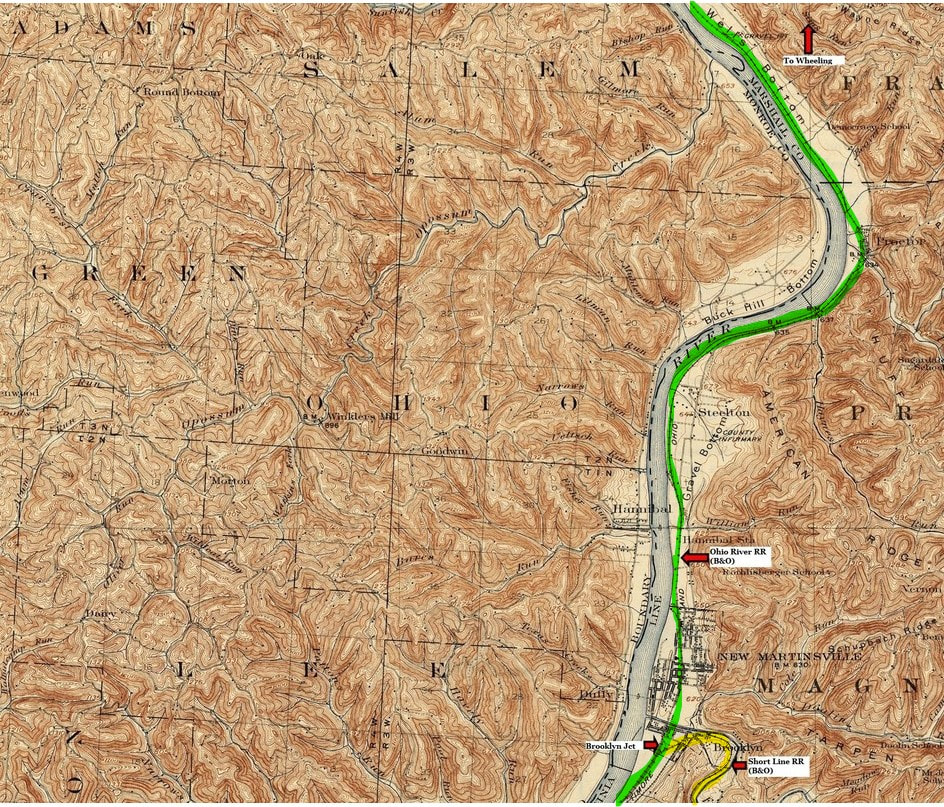

A 1924 topo map of the region extending from Wells Bottom in Marshall County to New Martinsville in Wetzel County. This area was home to industry during the B&O era and witnessed post World War II development. New Martinsville was an active junction with the Ohio River line (green) and the B&O Short Line (yellow) which ran to Clarksburg and remains so today with CSX.

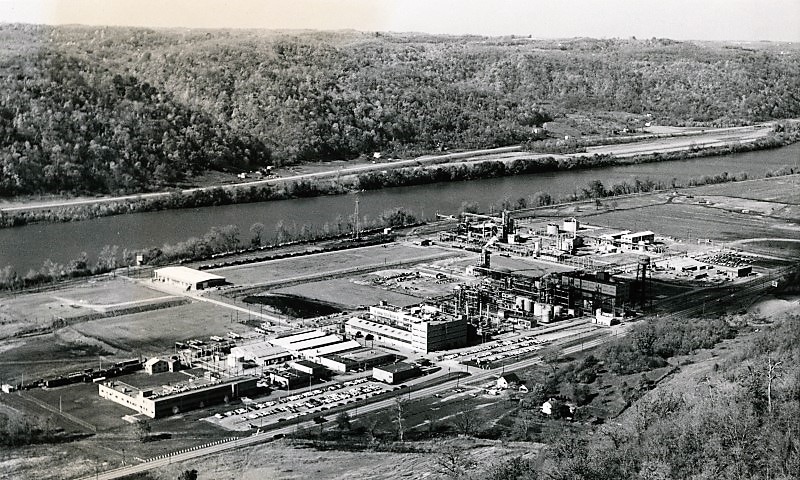

As the railroad moved west through Wells Bottom and approached the New Martinsville area, it touched a few more small communities as it crossed from Marshall into Wetzel County. In 1948, B&O listed the following companies as shippers in this bottom land area: Glyco Corporation, Pittsburgh Plate Glass and Chlorine, and the Wells Pit Sand Company. The region continued to develop in the post war era with the construction of the Mobay Chemical Plant in 1954, the first manufacturer of polyurethane in the world.

|

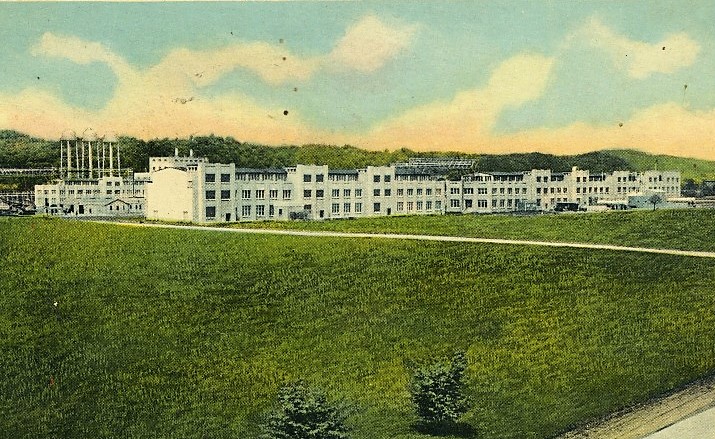

Modern industry began to develop in the Ohio valley during the 1940s. At the height of World War II, the Pittsburgh Plate Glass and Chlorine plant was constructed at Natrium in 1943. The company still exists today. Image Library of Congress

|

Postwar construction continued with the addition of the Mobay Chemical Plant at Natrium in 1954. This was a joint venture of Monsanto and Bayer Corporation and this company still operates today. Image West Virginia and Regional History

|

The new industry in the Wells Bottom area at the Marshall- Wetzel line resulted in a "new" community by the name of Natrium. B&O constructed a 5900 foot passing siding here that could also be utilized to switch the high volume of traffic at these plants. Today, the area has been further developed into the Bayer Industrial Park at New Martinsville which is generating traffic for CSX.

Once the railroad crossed into Wetzel County, the first community reached was Proctor. A depot was located here as well as a riverboat landing that thrived in the livestock business. B&O listed the Ohio River Sand Company as an active shipper still in existence during the late 1940s.On the outskirts of New Martinsville was located the whistle stop of Hannibal Station. This location was yet another passenger access added during the Ohio River Railroad era primarily to serve a town on the Ohio side of the river with ferry service operating between this stop and Hannibal, OH.

Once the railroad crossed into Wetzel County, the first community reached was Proctor. A depot was located here as well as a riverboat landing that thrived in the livestock business. B&O listed the Ohio River Sand Company as an active shipper still in existence during the late 1940s.On the outskirts of New Martinsville was located the whistle stop of Hannibal Station. This location was yet another passenger access added during the Ohio River Railroad era primarily to serve a town on the Ohio side of the river with ferry service operating between this stop and Hannibal, OH.

Steam along the Ohio. C&O #614 leads a Chessie Steam Special westbound by the river near Proctor circa 1980. The Chessie System operated several of these excursions lasting into the early 1980s. Photo Karl Underwood/Todd M. Atkinson collection

New Martinsville

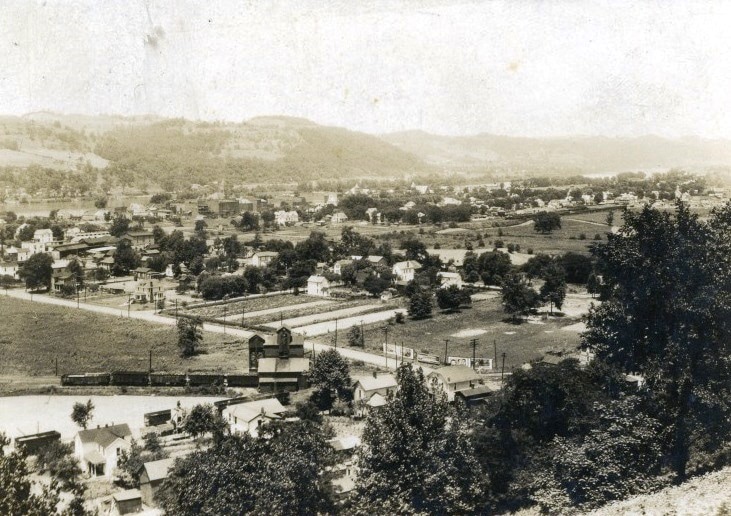

From the earliest years of its railroad history, New Martinsville became an important location on the fledgling Ohio River Railroad. Business developed along its rails in conjunction with its long established status as a river port. With the arrival of the West Virginia Short Line in 1895, it was the next rail junction west of Moundsville and provided an eastward connection to the B&O main line at Clarksburg. For nearly a century, New Martinsville was a terminal for passenger and freight traffic to and from the Ohio Valley primarily used as an auxiliary route. Changes in railroad operations during the 1960s and 1980s transformed the status of the junction at New Martinsville from a secondary to primary status.

|

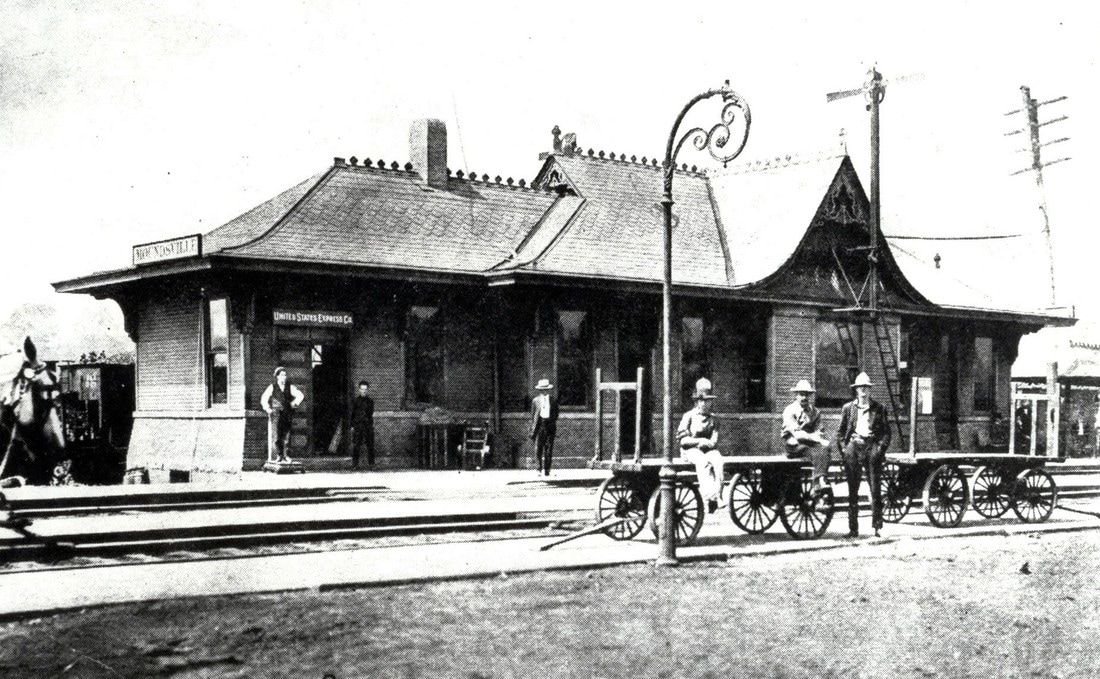

The New Martinsville depot during its halcyon years circa 1920. Passengers on both the B&O Ohio River line and the Short Line boarded and disembarked here. Image West Virginia and Regional History

|

Passenger trains were entering their twilight when this early 1950s photo was taken of a stop at New Martinsville. Before the end of the decade, this scene would no longer be repeated. Image John G. King/Dan Robie collection

|

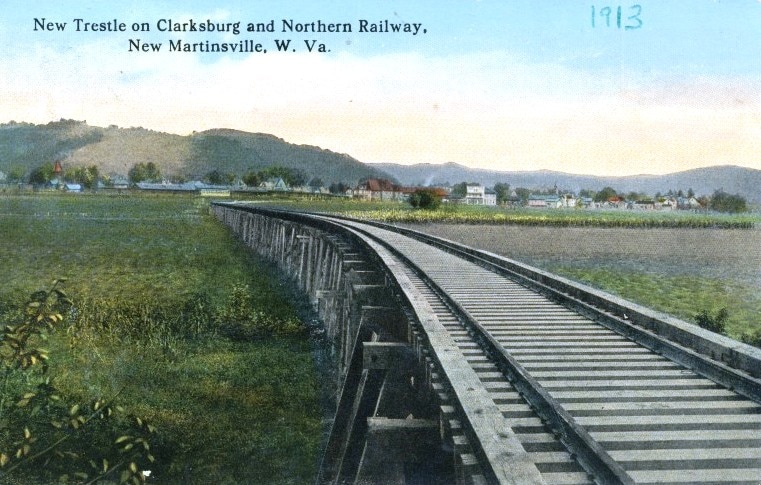

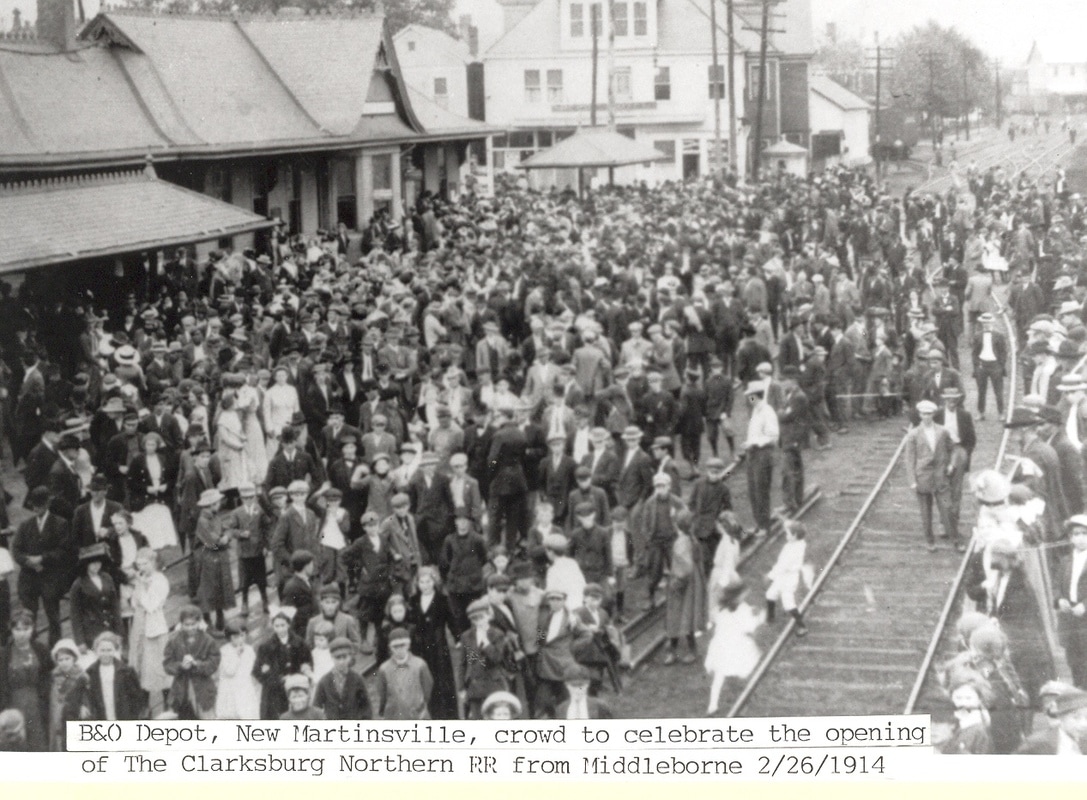

Yet another railroad touched New Martinsville in 1914 with the construction of the Clarksburg and Northern Railroad which provided freight and passenger service to Middlebourne in Tyler County. This railroad was completed with much fanfare as the inaugural service drew crowds at both Middlebourne and New Martinsville.

|

An elevated span of the Clarksburg and Northern Railway. Built on a trestle here to traverse bottom land near New Martinsville. Postcard image West Virginia and Regional History

|

A crowd gathers for the inaugural run of the Clarksburg and Northern Railway. This railroad connected the county seat of Tyler County--Middleborne-with New Martinsville and the B&O Ohio River line. Image John G. King/Dan Robie collection

|

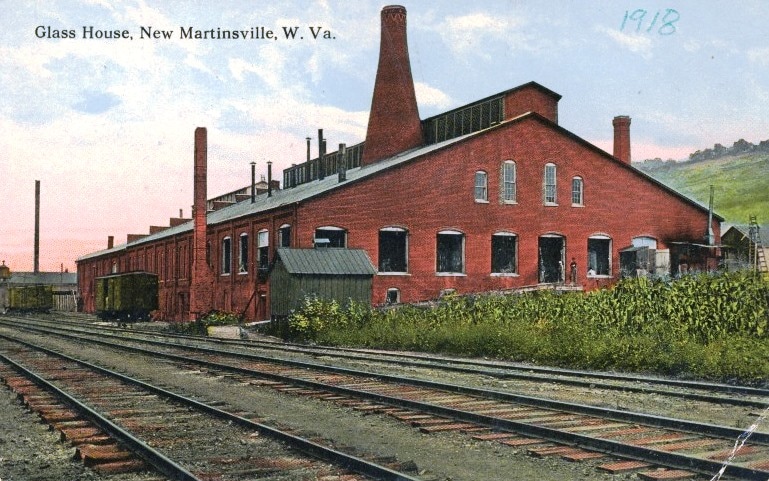

In addition to the postwar industrial development north (rail east) of New Martinsville, there were still several smaller shippers located along the Ohio River line as of the late 1940s. The region between Hannibal and New Martinsville contained the following: Ohio River Sand and Gravel #1, Viking Glass Company, Universal Concrete Products Company, Ohio River Sand and Gravel #2, New Martinsville Grocery Company, New Martinsville Supply Company and the Magnolia Fuel Supply Company. West of the New Martinsville station was the Abersold Oil Company, Wetzel Supply Company, Farm Bureau Services, and the E.F. Phillips Lumber Company. New Martinsville was assigned the call letters BJ (Brooklyn Junction) and an agent was on duty. B&O also listed the location as a coal and livestock watering stop.

|

The New Martinsville Glass plant as it appeared in 1918. One of several large plants in the area, this operation later became the Vulcan Glass Company. Postcard image West Virginia and Regional History

|

A view looking through Brooklyn into New Martinsville circa 1920s. The railcars and coal tipple at bottom are located on the Short Line. Image West Virginia and Regional History.

|

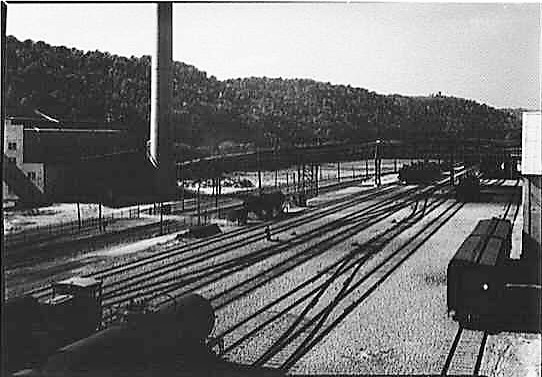

Freight operations at New Martinsville were and are based from the location known as Brooklyn Junction. Located on the west (south) bank of Fishing Creek from New Martinsville, this small community was eventually incorporated into the town but remained the base of railroad operations. The junction of the Short Line and the Ohio River line is that of a wye permitting movement to either direction on both lines. From the 1920s through the 1960s, an inner wye existed within the primary wye for the turning of locomotives. A yard also exists here that extends west for the classification of cars to local industry and return. During the B&O years, blocks of cars would be worked here for furtherance to other terminals. Operational changes during the Chessie System and CSX era increased the importance of the yard and terminal at New Martinsville. B&O began diverting trains from the old main line—Grafton to Wheeling—during the early 1960s over the Short Line thereby increasing activity there. Once the old main was abandoned and severed 1972-1974, all of its former volume began moving via New Martinsville.

|

The Chessie Steam Special moves eastbound through the bottom land near Hannibal. Karl Underwood/Todd M. Atkinson collection

At left: The C&O #614 is paused at MJ Tower in New Martinsville. The track diverging to left is north leg of the wye to the Short Line connection. Photo Karl Underwood/Todd M. Atkinson collection

|

B&O utilized an array of caboose classes and liveries throughout its storied history. This I-5 sporting yellow paint survived into the 1970s pictured here at New Martinsville on the rear of a train diverging from the Short Line. Image Adam Burns collection

New Martinsville briefly witnessed an increase of traffic during 1963 when the B&O Parkersburg line was closed between Clarksburg and Parkersburg to enlarge tunnel clearances. From May until November, all primary B&O St. Louis main line traffic---including passenger trains—was detoured over the Short Line to Parkersburg. As a result, spectators along the railroad between New Martinsville and Parkersburg were briefly treated to the passing of the National Limited and the Metropolitan Special. Two decades later, the rerouting of traffic became permanent when the St. Louis main was downgraded in 1985 and the Parkersburg Branch subsequently abandoned. Yet another significant change occurred in late 1985 when the PW&B line (Wheeling to Pittsburgh) was severed eliminating through traffic. Most facilities at Benwood were closed and yard volume dramatically reduced. Once into the CSX era, New Martinsville eclipsed Benwood as the primary yard in northwest West Virginia as volume dissipated from the Wheeling region. Today, the only through CSX trains at New Martinsville are Q316/Q317 and extra movements as well as a base for local switching trains.

Google Earth view of the topography and track layout at New Martinsville. The wye forms a triangle connection for the CSX Ohio River and Short Line Subdivisions with the yard to the west of the junction. Inside the wye is the terminal facility.

|

The afternoon sun glistens on SD60M# 8775 at New Martinsville. Moving through town with a maintenance of way train. Image Todd M. Atkinson 2013

|

Local power works a cut of cars next to the CSX yard office. This is the same vantage point as the Karl Underwood photo above from 30 years earlier. Image Todd M. Atkinson 2013

|

New Martinsville is one location remaining on the Ohio River line today where the main line is double tracked. This double track extends from Hannibal to through the yard area south of Brooklyn Junction and enables any through traffic to pass whereas the second track facilitates switching.

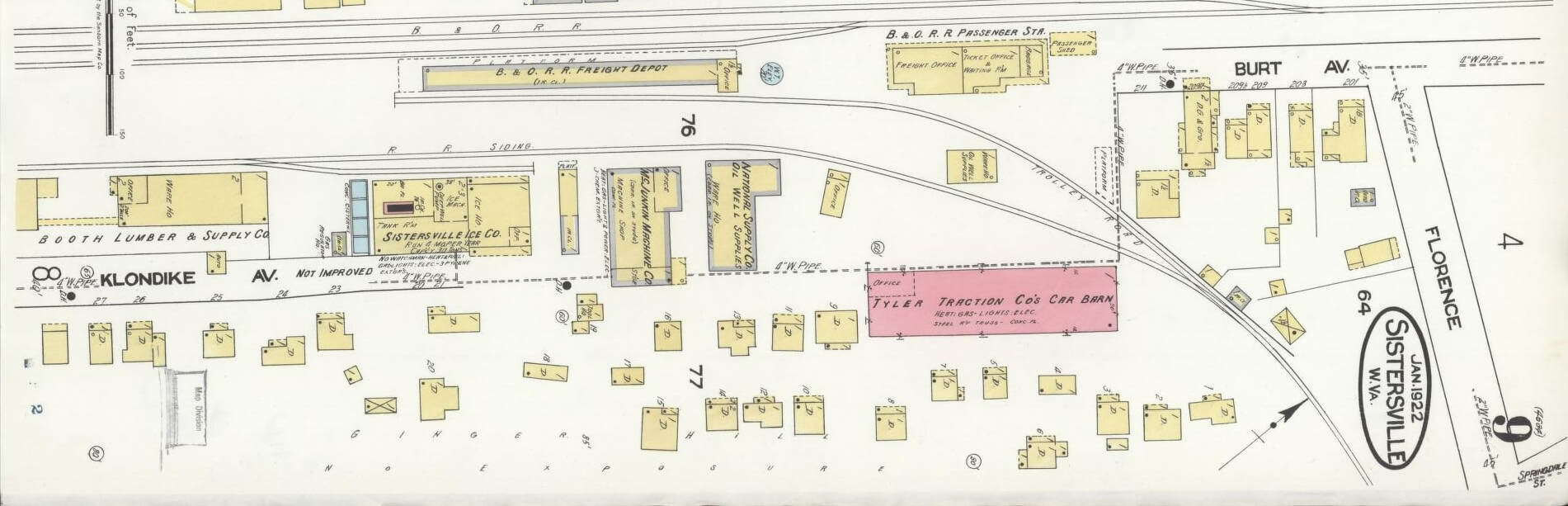

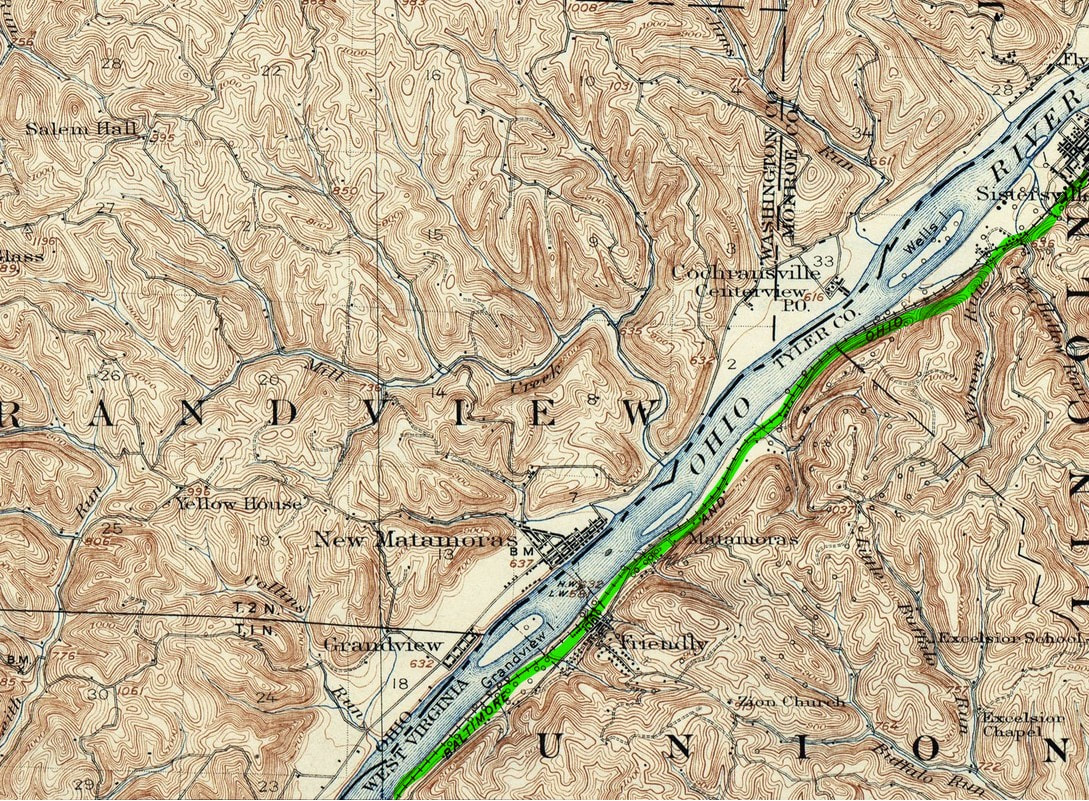

A 1924 topo map of the region from west of New Martinsville to Sistersville. The Ohio River Railroad (green) is closer to the river shore whereas the Tyler Traction Company, still in existence at this date, parallels the ORRR. Paden City became a commerce center for glass and pottery with Sistersville the site of a great oil boom during the 1890s. At right the B&O Short Line (yellow) parallels Fishing Creek east towards Clarksburg.

Straddling the Wetzel and Tyler County line, the next location to the west of consequence to the railroad was Paden City. Situated in a bottom between Paden and Williamson Islands in the Ohio River, the area remained agricultural until the beginning of the 20th century. With the coming of the Ohio River Railroad in 1884, the community began a transition to industry aided by natural resources in the region. By the early 1900s, Paden City had established itself as a glass making center with the most prominent business being the Paden City Pottery Company founded in 1911 which would earn world-wide acclaim for its products. Other early factories that emerged at Paden City during the Ohio River Railroad/early B&O era were the Paul Wissmach Glass Company, Duquesne Bottle Factory, Slider Brothers Cement Block Company, Euclid Manufacturing Company, Monongahela Iron and Steel Company and the Brown Lumber Company.

|

The B&O depot at Paden City circa 1920. In an era when passenger traffic was heavy, the photographer captured this idle scene but for the man on the hand car. Image John G. King/Dan Robie collection

|

An early view of the Paden City Glass Company as it appeared circa 1920s. One of several plants in a region rich with glass manufacturing. Image West Virginia and Regional History.

|

Fifty years later in 1950, B&O listed the following shippers still active at Paden City: Paul Wissmach Glass Company—which remains in business today, Paden City Pottery Company, Paden City Glass Company,

and the H. Bettis Company. This group of shippers still generated a volume of carloads for the railroad. Although railroad servicing facilities did not exist at Paden City, the B&O listed a 3200 foot passing siding here that certainly was used frequently as a runaround track to serve the local industries. The depot was of standard architecture used along the Ohio River and remained in service until the demise of passenger trains by the late 1950s.

and the H. Bettis Company. This group of shippers still generated a volume of carloads for the railroad. Although railroad servicing facilities did not exist at Paden City, the B&O listed a 3200 foot passing siding here that certainly was used frequently as a runaround track to serve the local industries. The depot was of standard architecture used along the Ohio River and remained in service until the demise of passenger trains by the late 1950s.

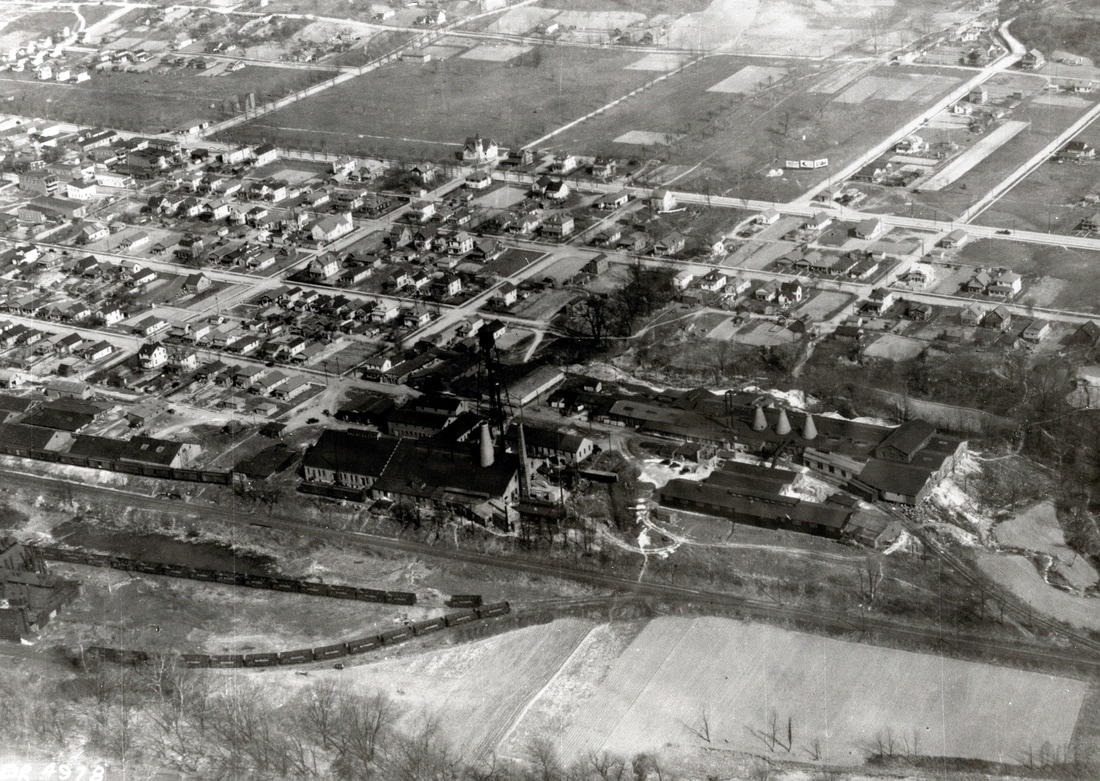

A circa 1930s era view of Paden City taken from above the Ohio River. The large industries visible here are the Paden City Glass Company and the world renowned Paden City Pottery Company. As evident, a considerable amount of carloads for the B&O when these businesses were in full bloom. Image John G. King/Dan Robie collection

During the time period of 1903-1930, Tyler County was the center of an interurban trolley system in addition to the primary Ohio River Railroad and later B&O. Sistersville was the focal point of these systems as all touched the community. In 1903 the Union Traction Company began operating an 11 mile line to New Martinsville that also served Paden City and Sistersville. This system also carried freight and mail and remained in existence until 1925 when the West Virginia State Road Commission purchased the right of way to construct State Route 2. 1905 witnessed the opening of a five mile line connecting Sistersville and Friendly. This railroad was built by the Parkersburg & Ohio Valley Electric railway and remained in service until 1918. The final traction line constructed was by the Tyler Traction Company connecting Sistersville and the county seat of Middlebourne. Thirteen miles in length, it remained in service until 1930 when it---like the others—succumbed to the automobile and developing road systems.

Sistersville

In 1802, Charles Wells migrated down the Ohio River from Wellsburg and established a settlement at “Long Reach”—an uncharacteristic 20 mile straight stretch in the river course. In addition to vast farmland, he operated a tavern and remained in the area until his death in 1815. Wells left his estate to two daughters, Sarah and Delilah, and the two sisters laid out plots for a town that would be named in their honor, Sistersville.

|

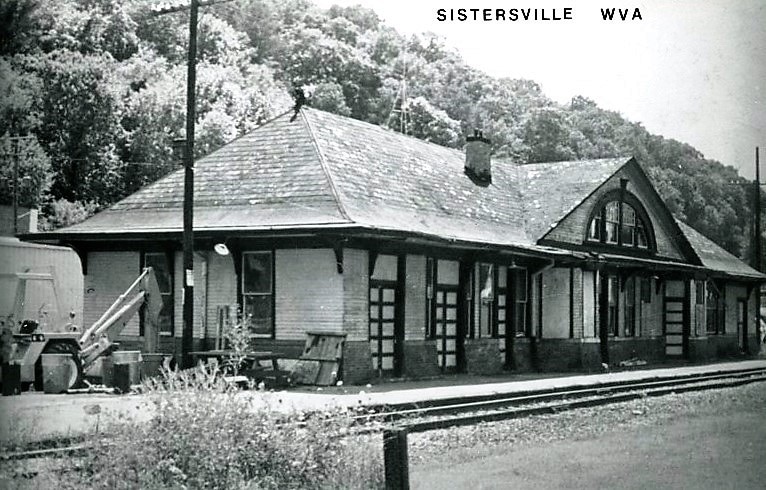

Sistersville was manned by a station agent and with the telegraph call letters (QN). Coal and water were among the servicing facilities remaining in existence by the late 1940s in addition to a 3100-foot passing siding. Today, CSX trains continue to pass through Sistersville although no online shippers remain. The city has reverted to its pre oil boom era of primarily a residential community along the river. An exploration along the railroad, however, will reveal secrets of its industrial past. On another note and although non- rail in nature, it is the location of the last operating river ferry in the state connecting Sistersville with Fly, OH.

|

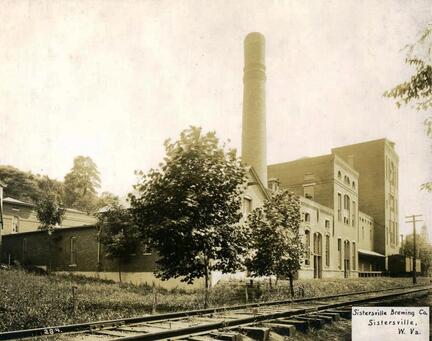

At right: An early industry was the Sistersville Brewing Company founded in 1906. It later became the Ohio River Brewing Company but was defunct by 1911. Image West Virginia and Regional History

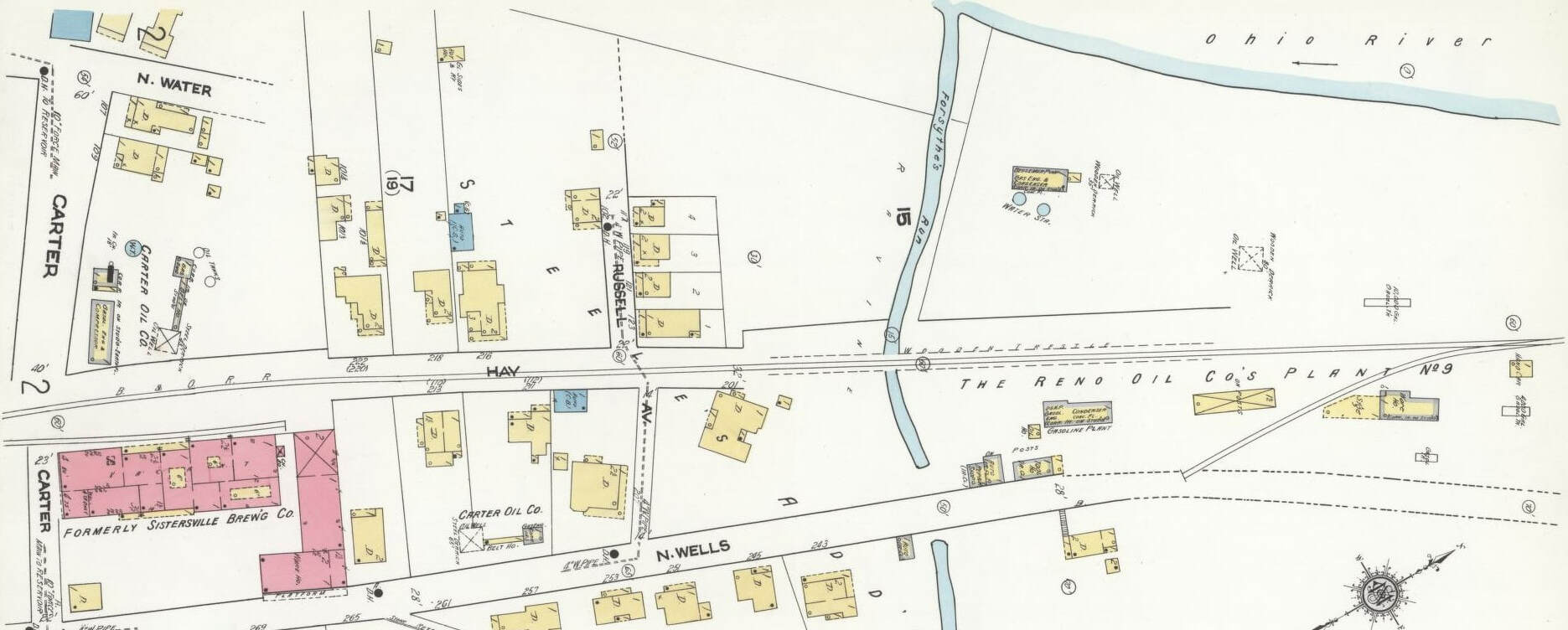

The north end (railroad east-right side of map) of Sistersville was the domain of the Reno Oil Company Plant #9 and the Sistersville Brewing Company. During the first half of the 20th century, even the smaller towns hosted multiple shippers served by rail. Sadly, many no longer retain a single shipper today.

|

The B&O Sistersville station during the golden years circa 1920. This structure was larger and more ornate than the majority of the depots on the line owing to its importance. Image John G. King/Dan Robie collection

|

Passenger trains and boom times were a memory when this 1960s era photo was taken. The station has taken on a forlorn appearance. Image John G. King/Dan Robie collection

|

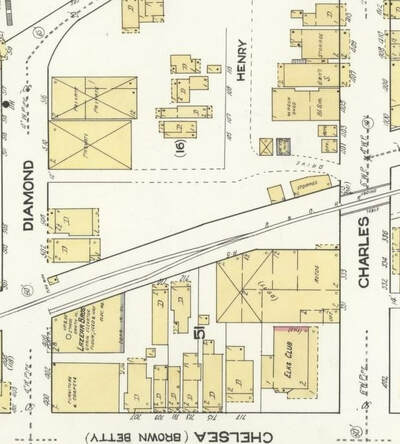

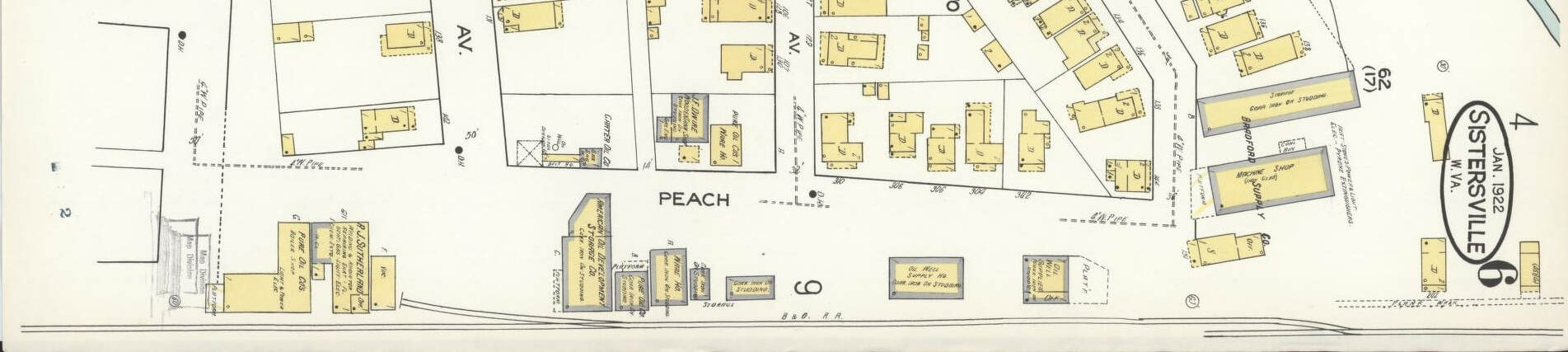

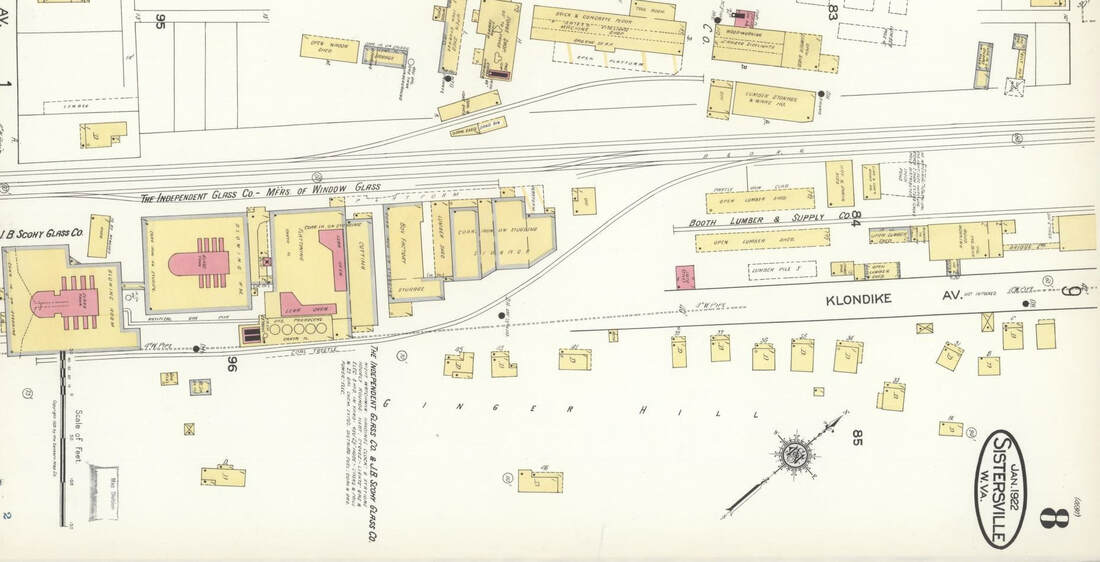

In 1922, the rail center of Sistersville was further north from its present- day limits. Not only were both the freight and passenger stations located here but also the Tyler County Traction barn. Industry such as the Booth Lumber and Supply and the Sistersville Ice Company also occupied this area of town. (North is right side of map)

|

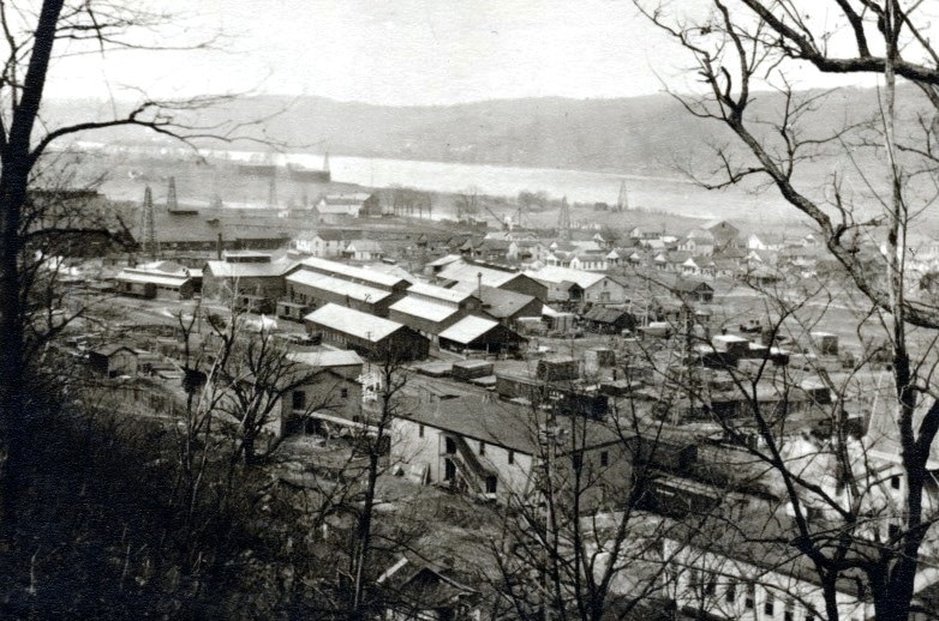

Sistersville is prominent in early West Virginia industrial history for it was here that one of the great oil fields was discovered in 1891. It is also notable in the brief history of the Ohio River Railroad because not only was it a boon to the fledgling railroad but the peak years of the Sistersville field occurred entirely prior to the B&O. With the discovery of oil, Sistersville literally became a boom town overnight. The town rapidly expanded from the oil strike and the supporting businesses to accommodate it. The population prior to the oil discovery was approximately 300; by the mid-1890s, the number reached 15,000. During this era, the passenger service on the railroad was immense serving both the populace and industrial firms. The oil field continued to consistently produce but once into the first decade of the 20th century, it was in decline.

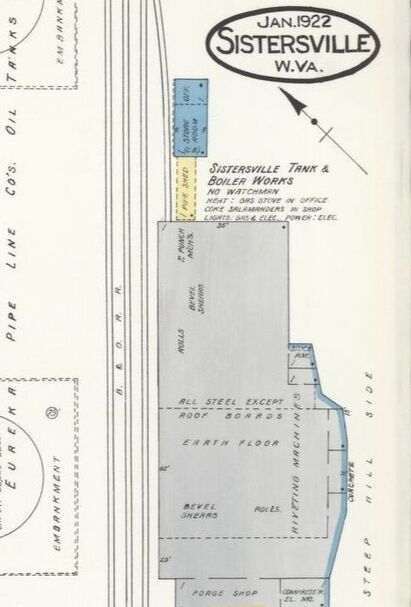

Affiliated with the early oil industry was the Sistersville Tank and Boiler Works. This operation also utilized a rail spur for shipments as necessary.

|

Sistersville during the era of the great oil boom circa 1900. Wells were drilled virtually everywhere as evidenced by the numerous derricks and industrial buildings populate the landscape furnishing equipment and other supplies. A substantial amount of business for the Ohio River Railroad. Image West Virginia and Regional History.

|

Other businesses that spawned in the area were associated with the oil and gas industry. By the 1940s, a number of businesses served by the B&O remained in existence although the oil boom itself was but a memory. A list of these shippers includes American Oil and Development Company, Hope Construction and Refining Company, Standard Oil, Sistersville Refining Company, and the Quaker State Oil Refining Company. Other shippers not related to oil and gas comprised of the Bowser Lumber and Feed Company, Sistersville Tank and Boiler Works, and the West Virginia State Road Commission.

A long vanished shipper in the heart of Sistersville was the Lazear Brothers loacted between Charles and Diamond Streets. Feed and fertilizer were the commodities.

|

Sistersville in 1922 included smaller shippers for the railroad that accounted for carloads and revenue. Towards the south end of town were R. J Sutherland, Pure Oil, and the American Oil Development Storage Company. (North at right side of map)

At the south end of Sistersville was an industrial pocket that included shippers such as the J. B Scomy Glass Company and the Independent Glass Company. Booth Lumber and Supply also utilized a spur at this end of town. (North at right side of map)

|

CSX SD50 #8509 leads an empty hopper train through Sistersville in 1993. The trackside house would be a delight for many a railfan. Image Todd M. Atkinson 1993

|

Q316 moves through tight confines at Sistersville. SD40-2 #8056 leads a gaggle of other as the train makes its eastbound trek amidst the changing foliage of early autumn. Image Todd M. Atkinson 1999

|

A 1924 topo map of the region known as "Long Reach" where the Ohio River runs a straight course. West of Sistersville, this area includes the town of Friendly with the B&O continuing to parallel the river. Gone by this date was the trolley route that extended from Sistersville to Friendly.

A small community with a welcoming name to the west of Sistersville is Friendly. First established during the Revolutionary era of 1785 by Thomas and John Williamson, the town was first known as Fairview. It was later renamed after the grandson of Thomas Williamson, Friend Cochran Williamson. When the township was incorporated in 1883, its name became the modified version of Friendly. By the 1890s, the town had grown with the construction of a flour mill and a lumber mill in addition to a passenger depot. It is likely that the Ohio River Railroad served both of these businesses and perhaps continuing into the early B&O era. In the postwar era of the late 1940s, B&O recorded no shippers at Friendly but a 2600 foot passing siding was still in use.

|

Train time at Friendly circa 1910. Given the size of the community, a large number of people are gathered to board the train west along the Ohio River. Image John G. King/Dan Robie collection

|

Nearly a century later, CSX Q317 parallels the broad Ohio River at Friendly. Despite uncounted changes, the line retains its river side charm. Image courtesy Bill Gawthrop

|

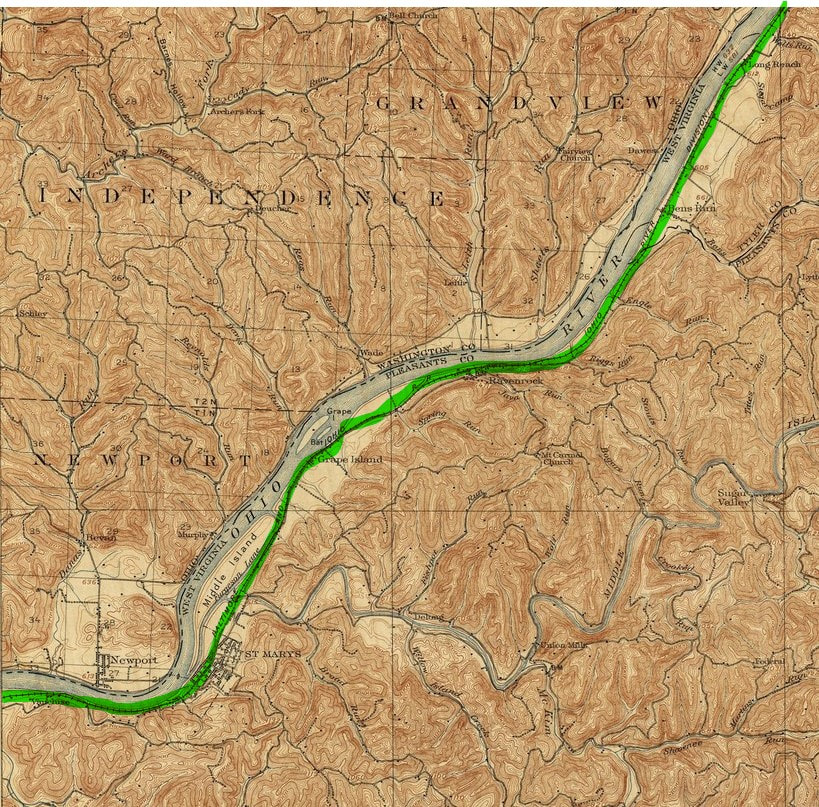

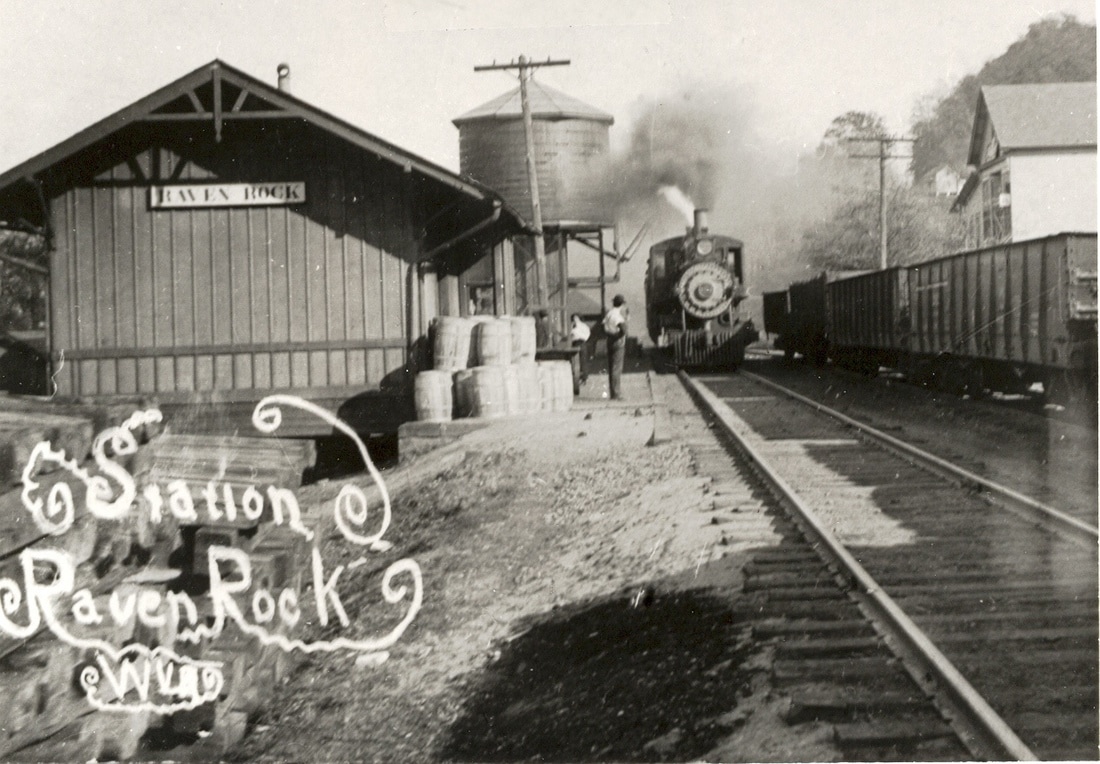

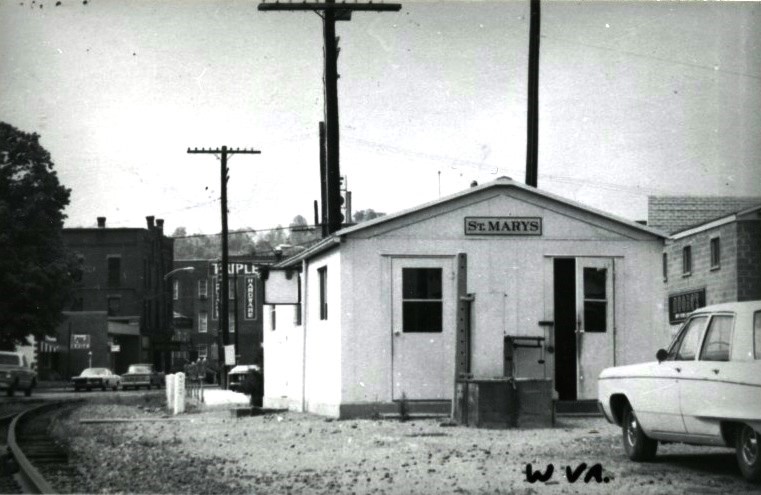

Continuing its westward trek, the Ohio River Railroad moves into Pleasants County passing through Long Reach, Bens Run, Raven Rock, and Grape Island. At the mouth of Middle Island Creek is St. Marys, a notable location on the railroad both yesterday and today.

Named for the lengthy straight stretch of the Ohio River, the community of Long Reach was a flag stop along the railroad. B&O listed no shippers during the 1940s but the area later became a source of rail revenue with the construction of an industrial park. A CSX shipper within the park is the Chemtura Corporation.

A head on collision at Bens Run in 1910. One train failed to take the siding here for the other to pass resulting in this accident. In early years before automatic signaling or on lines requiring train orders, head on collisions were more common than today. John G. King/Dan Robie collection

The same siding at Bens Run nearly a century later as Q316 (foreground) meets its westbound counterpart, Q317. Conrail had just been split up between CSX and NS---SD40-2 #3408 is a NS locomotive--and its blue locomotives would be common on both roads for another decade. Image Todd M. Atkinson 1999

Bens Run was and is an important passing siding location along the railroad since the Ohio River Railroad era. In 1948, B&O listed a 5900 foot siding here--the longest on the route. No shippers of consequence were listed here but it was a busy location along the line due to meets. A long siding remains here today for CSX. In fact, it is the only passing siding still in existence between Parkersburg and Benwood. Modern times witnessed the development of a Union Carbide plant here that generated carloads for the railroad.