Parkersburg to Clarksburg-Waist of the B&O Main

part i

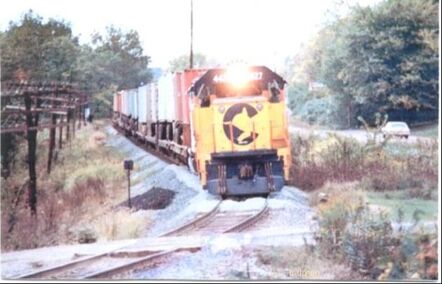

The late summer night temperature was in the mid-sixties for one who may have been standing at the Parkersburg High Yard during the early morning hours of August 31, 1985. As the city still slept, a headlight emerged in the distance from the east with the approach of a train as had happened many thousands of times before. The familiar sound of EMD locomotives gained in pitch as the train approached the beginning of the yard near the former location of SY Tower. As it moved into the yard, one would have seen a trio of GP40-2s with B&O #4136, B&O #4434, and C&O #4415 on the lead with a historical train of sorts. This was Train 89 that departed Grafton earlier and made its run over the Parkersburg Branch passing through the sleepy towns and tunnels that dotted the 104-mile run during the dead of night. One of uncounted trains to pass over these rails between Grafton and Parkersburg, it nonetheless was one of the most significant. After 128 years of existence, this was the last regularly scheduled timetable train to traverse the Parkersburg Branch.

Prologue

It has been almost three decades now since the towns and hollows between Parkersburg and Clarksburg last echoed with the sound of passing trains. A constant mainstay that was as common as mail delivery and passing automobile traffic, the railroad abruptly fell silent in 1985 ending a century and a quarter of what was perceived as everyday life. Local folks living along the route who were not necessarily privy to goings on of the railroad at some point were surely stricken with the curiosity of what happened to the trains and later bewildered as the track was being removed. All that was---the people, the trains, prosperity and depression, and sadly, the tragedies suffered by towns and railroad alike---combine to form this unique chapter of West Virginia and Baltimore and Ohio Railroad history coming to an end. The fine people of Wood, Ritchie, Doddridge, and Harrison Counties have done well to preserve this deep rooted heritage.

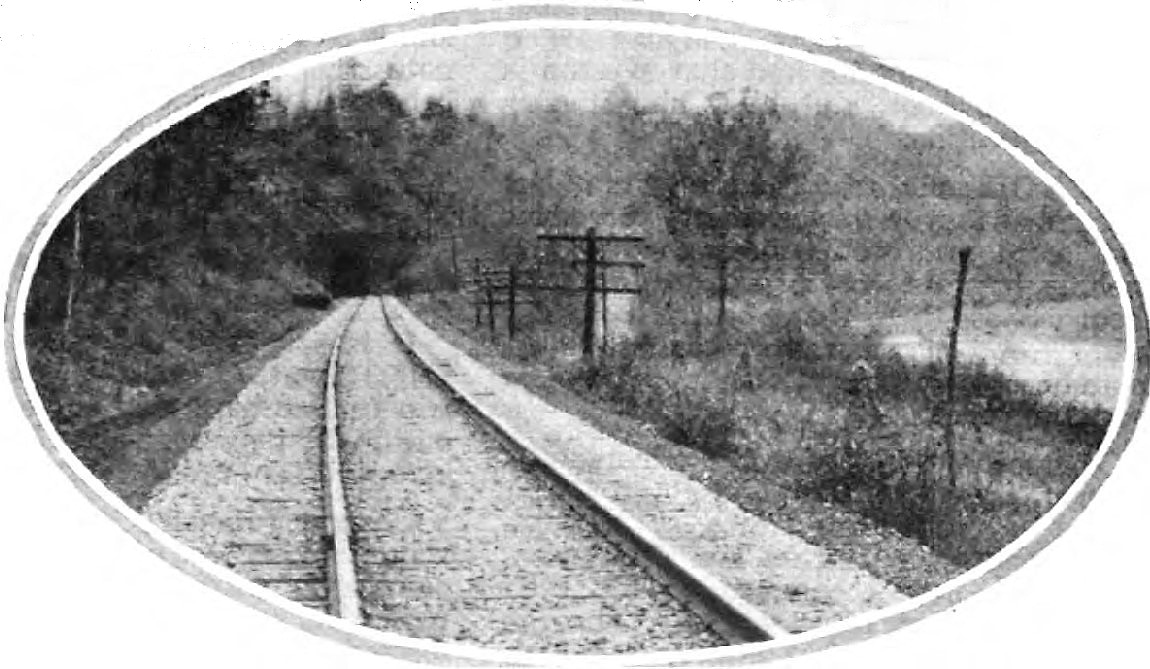

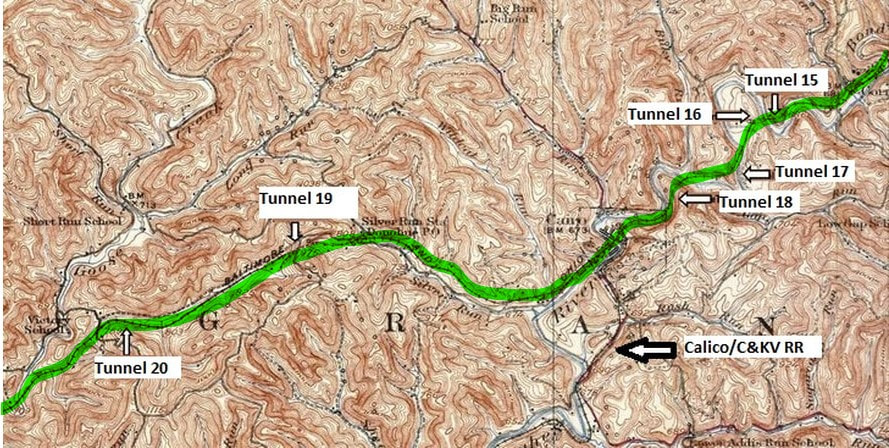

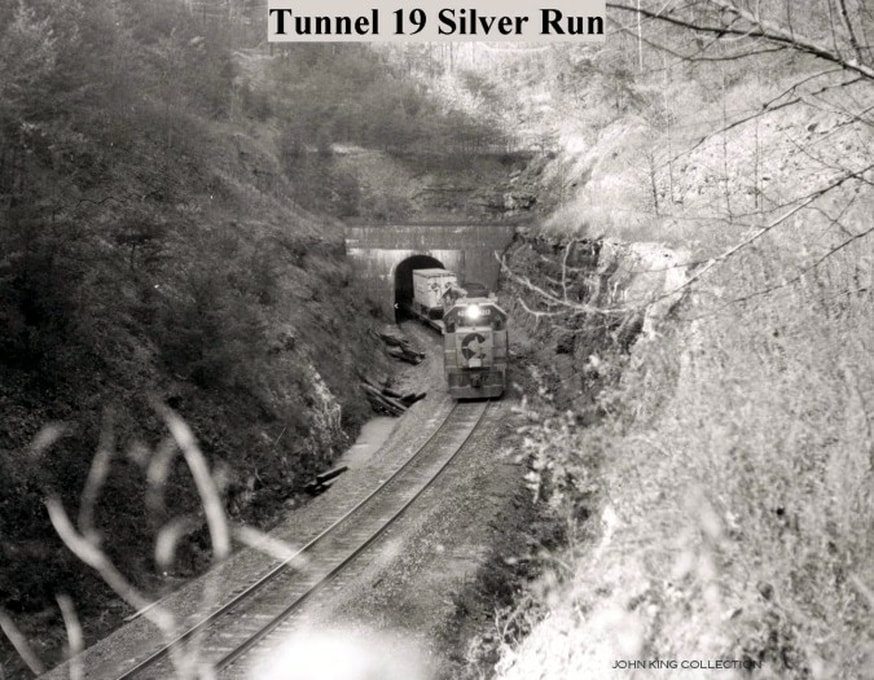

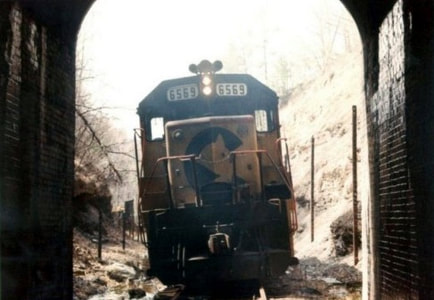

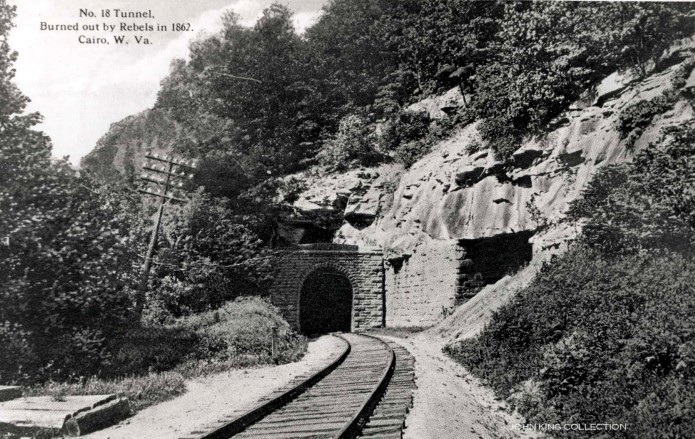

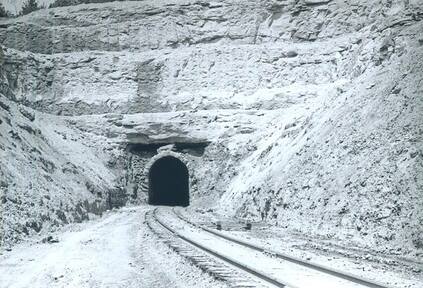

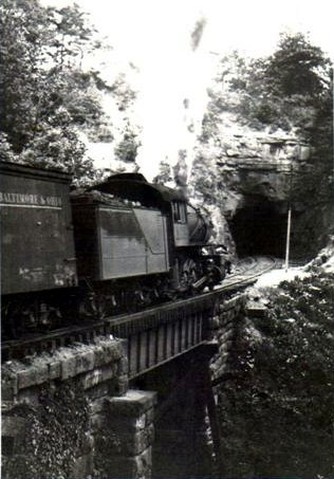

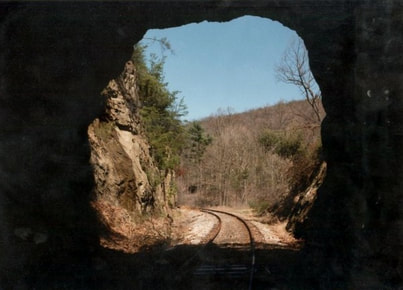

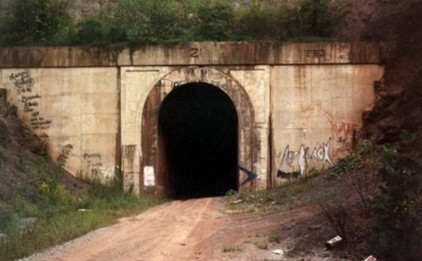

Known in B&O railroad circles simply as “The Branch”, the line from Grafton to Parkersburg indeed began life as one but ultimately became a link in a substantially larger corridor. As the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad expanded west through construction and acquisitions, the Parkersburg Branch became a section of a trunk mainline extending from Cumberland to St. Louis. Its route was strategic as a gateway railroad connecting the East Coast with the Midwest and for well over a century filled this role transporting freight and passengers to points close and afar. The territory the railroad traversed was archetypal West Virginia passing through small towns yet servicing with more complexity the cities of Parkersburg and Clarksburg. It possessed a charm that harkened to earlier times as much of the landscape along the route remained the same. As the railroad passed through northern West Virginia, it wound through the creek valleys touching the towns and crossing the drainage basins on numerous bridges. Unquestionably were the tunnels that defined the Parkersburg Branch. These were the signature element of the line and embellished its existence as a fascinating section of railroad. Mark Twain referred to it "as the longest subway in the world". In the later years of the Branch, these tunnels, unique from a rail enthusiast perspective, would prove to be more of a liability.

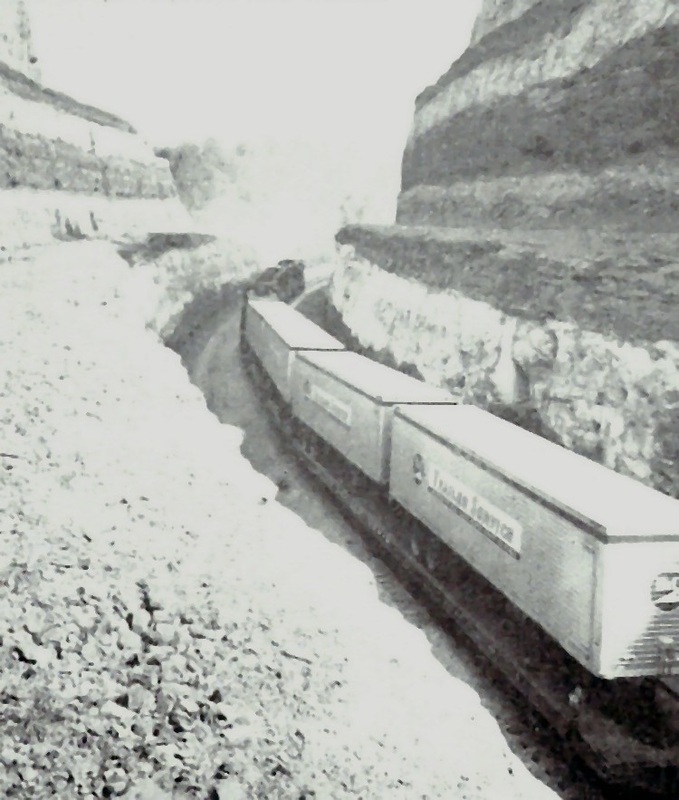

Many B&O name trains passed over these rails. Time (QD) freights such as Gateway 97, Cincinnati 97, and Cumberland 94 were staples for many years. Later years witnessed the advent of trailer on flat car trains (TOFC) such as the Manhattan and St. Louis Trailer Jets. During the glory years of passenger trains, the stately National Limited along with the Diplomat and the elegant but ill-fated Cincinnatian called the Branch home. Added to this are a multitudes of other named and unnamed trains, freight and passenger, local and long distance that ran the route. Presidents, the famous and near famous, but mainly people going about life in anonymity, rode its rails by the thousands for more than one hundred years. All were afforded superior service that was a hallmark of the B&O.

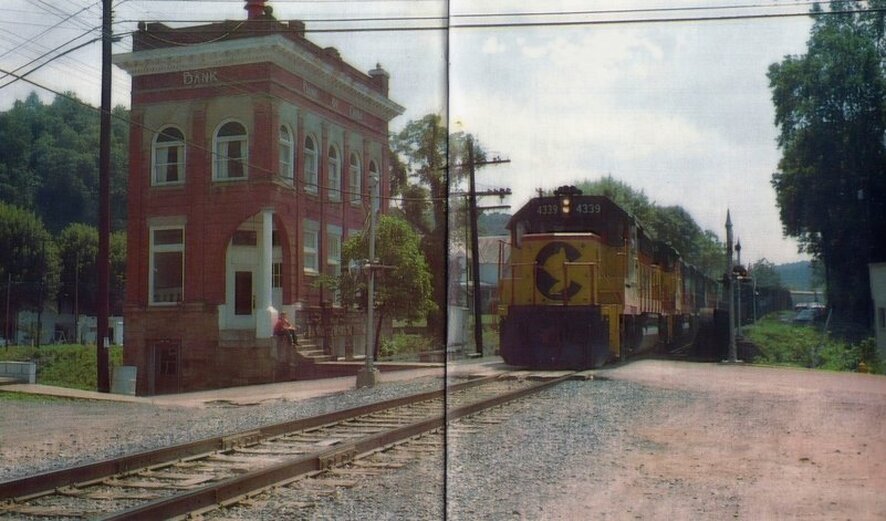

In 1985, all that was came to end. The Chessie System, itself on the eve of transition into CSX Transportation, dropped what was considered a bombshell at the time announcing that the railroad between Cumberland and Cincinnati would be downgraded from mainline status. Within three years, all operations had ceased, and track removal began between Parkersburg and Clarksburg eliminating the railroad altogether. This was a controversial abandonment both in railroad circles and the rail enthusiast community that continues as a topic of debate to this day. Whether perceived or real be it sentiment or shortsightedness, pros and cons simultaneously coexist on the impact of this decision in the context of past, present, and future.

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad has a storied history and is well documented. Published volumes are bountiful but a glaring exception to this is relatively few works that cover the mainline west of Grafton onward to St. Louis. Smaller population densities and access to rural locales likely account for the primary reason of limited coverage and the Parkersburg Branch fits firmly in this category. Lack of operation was certainly not a factor. As a result, photographs and reference material are surprisingly sparse for a route that was prominent in the B&O network. In a related matter, the Parkersburg Branch is the source of my greatest historical rail regret. My work travels during the early 1980s took me to locations between Parkersburg and Clarksburg and I would see trains on the line on most of those forays. Regrettably, a camera did not accompany my other tools and the rationalization set in that I would take photos "someday". Needless to say, someday came and went in 1985 and the opportunities were lost forever.

I have opted to exclude Grafton from this piece although there will be references to it in the content. The reasons for this are twofold. First, the focus here is on the abandoned section of the Parkersburg Branch although Parkersburg and Clarksburg still retain active service. Second and most importantly, Grafton is a dynamic location in B&O history and still a player in modern day CSXT operations. Quite simply, it is a volume of and in itself that has been a subject covered by noted published authors such as Jay Potter and Bob Withers among numerous others. Any in depth effort on my part would pale in comparison although I do plan to include a general page about Grafton in the future.

CSXT operations will not be included in this page but for few exceptions. These will only be used as a basis for comparison and a discussion summary of the post 1985 abandonment. At first, I considered including CSXT images in this piece but decided that separate articles in the future would be more suited for that purpose.

Finally, readers who are familiar with the Parkersburg Branch and its history will undoubtedly recognize many of the images contained herein as they appear on other web pages or in the common domain. Through the generosity of these individuals and organizations, I have been graciously permitted to share them on this page for the creation of this piece. These contributors will be listed in the credits at the conclusion.

Known in B&O railroad circles simply as “The Branch”, the line from Grafton to Parkersburg indeed began life as one but ultimately became a link in a substantially larger corridor. As the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad expanded west through construction and acquisitions, the Parkersburg Branch became a section of a trunk mainline extending from Cumberland to St. Louis. Its route was strategic as a gateway railroad connecting the East Coast with the Midwest and for well over a century filled this role transporting freight and passengers to points close and afar. The territory the railroad traversed was archetypal West Virginia passing through small towns yet servicing with more complexity the cities of Parkersburg and Clarksburg. It possessed a charm that harkened to earlier times as much of the landscape along the route remained the same. As the railroad passed through northern West Virginia, it wound through the creek valleys touching the towns and crossing the drainage basins on numerous bridges. Unquestionably were the tunnels that defined the Parkersburg Branch. These were the signature element of the line and embellished its existence as a fascinating section of railroad. Mark Twain referred to it "as the longest subway in the world". In the later years of the Branch, these tunnels, unique from a rail enthusiast perspective, would prove to be more of a liability.

Many B&O name trains passed over these rails. Time (QD) freights such as Gateway 97, Cincinnati 97, and Cumberland 94 were staples for many years. Later years witnessed the advent of trailer on flat car trains (TOFC) such as the Manhattan and St. Louis Trailer Jets. During the glory years of passenger trains, the stately National Limited along with the Diplomat and the elegant but ill-fated Cincinnatian called the Branch home. Added to this are a multitudes of other named and unnamed trains, freight and passenger, local and long distance that ran the route. Presidents, the famous and near famous, but mainly people going about life in anonymity, rode its rails by the thousands for more than one hundred years. All were afforded superior service that was a hallmark of the B&O.

In 1985, all that was came to end. The Chessie System, itself on the eve of transition into CSX Transportation, dropped what was considered a bombshell at the time announcing that the railroad between Cumberland and Cincinnati would be downgraded from mainline status. Within three years, all operations had ceased, and track removal began between Parkersburg and Clarksburg eliminating the railroad altogether. This was a controversial abandonment both in railroad circles and the rail enthusiast community that continues as a topic of debate to this day. Whether perceived or real be it sentiment or shortsightedness, pros and cons simultaneously coexist on the impact of this decision in the context of past, present, and future.

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad has a storied history and is well documented. Published volumes are bountiful but a glaring exception to this is relatively few works that cover the mainline west of Grafton onward to St. Louis. Smaller population densities and access to rural locales likely account for the primary reason of limited coverage and the Parkersburg Branch fits firmly in this category. Lack of operation was certainly not a factor. As a result, photographs and reference material are surprisingly sparse for a route that was prominent in the B&O network. In a related matter, the Parkersburg Branch is the source of my greatest historical rail regret. My work travels during the early 1980s took me to locations between Parkersburg and Clarksburg and I would see trains on the line on most of those forays. Regrettably, a camera did not accompany my other tools and the rationalization set in that I would take photos "someday". Needless to say, someday came and went in 1985 and the opportunities were lost forever.

I have opted to exclude Grafton from this piece although there will be references to it in the content. The reasons for this are twofold. First, the focus here is on the abandoned section of the Parkersburg Branch although Parkersburg and Clarksburg still retain active service. Second and most importantly, Grafton is a dynamic location in B&O history and still a player in modern day CSXT operations. Quite simply, it is a volume of and in itself that has been a subject covered by noted published authors such as Jay Potter and Bob Withers among numerous others. Any in depth effort on my part would pale in comparison although I do plan to include a general page about Grafton in the future.

CSXT operations will not be included in this page but for few exceptions. These will only be used as a basis for comparison and a discussion summary of the post 1985 abandonment. At first, I considered including CSXT images in this piece but decided that separate articles in the future would be more suited for that purpose.

Finally, readers who are familiar with the Parkersburg Branch and its history will undoubtedly recognize many of the images contained herein as they appear on other web pages or in the common domain. Through the generosity of these individuals and organizations, I have been graciously permitted to share them on this page for the creation of this piece. These contributors will be listed in the credits at the conclusion.

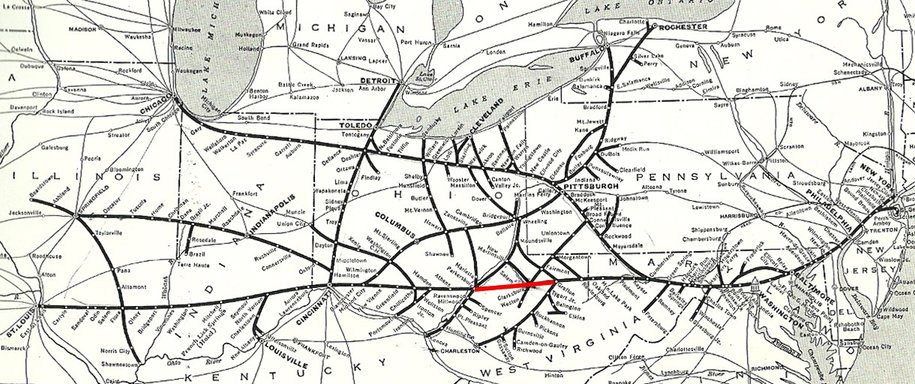

An often-published company map depicting the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad near its peak. The Parkersburg Branch is highlighted in red outlining its location within the St. Louis main line and its relationship to B&O network as a whole. In addition to most of the Parkersburg Branch, there are numerous other lines on this map that no longer exist.

Condensed History

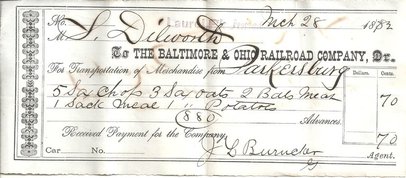

The railroad that would become the Parkersburg Branch was among the earliest built lines in America. Predating the Civil War by a decade, it was chartered as the Northwestern Virginia Railroad (NVRR) in 1851 by the Virginia Legislature then subsequently backed by a group of Parkersburg businessmen as a precursor to future expansion and industrialization. Financing was provided by the City of Baltimore with a 1.5 million dollar loan and the B&O, with aspirations clearly on this route, contributed a like amount for the construction which commenced in 1852.

A number of political and business ventures were simultaneously in play with the construction of the Northwestern Virginia Railroad. B&O was completing its mainline from Cumberland to Wheeling precipitated by political pressure from both the City of Wheeling and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The pressure from Wheeling was for the city to become the Ohio River terminus. Political forces in Pennsylvania coerced the route of its construction by not granting the railroad access to be constructed within its borders; hence, the tortuous route over the Alleghenies from Cumberland to Grafton and furtherance to Wheeling on a circuitous route.

A number of political and business ventures were simultaneously in play with the construction of the Northwestern Virginia Railroad. B&O was completing its mainline from Cumberland to Wheeling precipitated by political pressure from both the City of Wheeling and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The pressure from Wheeling was for the city to become the Ohio River terminus. Political forces in Pennsylvania coerced the route of its construction by not granting the railroad access to be constructed within its borders; hence, the tortuous route over the Alleghenies from Cumberland to Grafton and furtherance to Wheeling on a circuitous route.

B&O fulfilled the building of the railroad to Wheeling not only from commitment but because it would be a profitable undertaking as well. But as early as the 1840s, it already had its eyes on westward expansion by building a more direct line connecting the markets of Cincinnati and St. Louis. Thus, it was no surprise that the B&O was firmly invested in the construction of the Northwestern Virginia Railroad for it was the initial step in the expansion to the Midwest. Once the railroad was completed between Grafton and Parkersburg in 1857, B&O set its sights on taking outright control. In 1856, the B&O and NVRR had signed an agreement whereas the former would complete the building of the road and operate the line for five years.

The Civil War wrought havoc on the B&O because of its strategic location as a borderline between the North and South. For the first time in history, the railroad became a military priority both in the transport of troops and material as well as a key target for the disruption of such. The campaigns in Western Virginia during the outset of the war are lesser known than in the East, but it was here that the railroad first demonstrated its impact on modernizing warfare. The Northwestern Virginia Railroad played a vital role in the transport of Union troops from Ohio to the East and the area was subject to raids by the Confederates attempting to thwart these movements. Similarly, Western Virginia was a tinderbox of divided loyalties and forces were in motion that eventually led to the creation of the pro union West Virginia in 1863. The B&O, through means direct and indirect, played a role in the formation of the new state born amidst the turmoil of war.

The Civil War wrought havoc on the B&O because of its strategic location as a borderline between the North and South. For the first time in history, the railroad became a military priority both in the transport of troops and material as well as a key target for the disruption of such. The campaigns in Western Virginia during the outset of the war are lesser known than in the East, but it was here that the railroad first demonstrated its impact on modernizing warfare. The Northwestern Virginia Railroad played a vital role in the transport of Union troops from Ohio to the East and the area was subject to raids by the Confederates attempting to thwart these movements. Similarly, Western Virginia was a tinderbox of divided loyalties and forces were in motion that eventually led to the creation of the pro union West Virginia in 1863. The B&O, through means direct and indirect, played a role in the formation of the new state born amidst the turmoil of war.

The NVRR, with meager capital assets, could not pay off its debts and the B&O purchased the line at foreclosure in 1865. The railroad had taken its first major step towards moving westward beyond the Ohio River. What would remain in name throughout its existence as the Parkersburg Branch would ultimately become a divisional segment of a mainline extending from Cumberland to St. Louis.

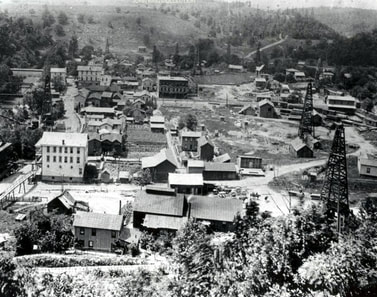

After the Civil War, railroad expansion accelerated and scores of communities located along the rails prospered with the onset of the Industrial Revolution. Most notably along the Parkersburg Branch were the cities of Parkersburg and Clarksburg. The former, located along the commercially viable Ohio River, became a gateway between East and Midwest by virtue of water and rail. Industry sprang up along the Branch and once the Ohio River Railroad was completed in 1888, Parkersburg was an axis of rail lines east, west, north and south. Further development in the Ohio Valley provided the Branch with additional freight revenue. Until 1871, traffic crossing the Ohio River into Ohio to points west and vice versa, had to be ferried fourteen miles to the connection at Marietta. The construction of the Ohio River bridge connecting Parkersburg and Belpre, OH in 1871 eliminated this tedious transfer of freight and passengers thereby drastically increasing the expediency of the railroad. Considered an engineering marvel, the Ohio River bridge was the longest of its type in the world for a number of years. Even today, it is an impressive structure to behold.

After the Civil War, railroad expansion accelerated and scores of communities located along the rails prospered with the onset of the Industrial Revolution. Most notably along the Parkersburg Branch were the cities of Parkersburg and Clarksburg. The former, located along the commercially viable Ohio River, became a gateway between East and Midwest by virtue of water and rail. Industry sprang up along the Branch and once the Ohio River Railroad was completed in 1888, Parkersburg was an axis of rail lines east, west, north and south. Further development in the Ohio Valley provided the Branch with additional freight revenue. Until 1871, traffic crossing the Ohio River into Ohio to points west and vice versa, had to be ferried fourteen miles to the connection at Marietta. The construction of the Ohio River bridge connecting Parkersburg and Belpre, OH in 1871 eliminated this tedious transfer of freight and passengers thereby drastically increasing the expediency of the railroad. Considered an engineering marvel, the Ohio River bridge was the longest of its type in the world for a number of years. Even today, it is an impressive structure to behold.

Clarksburg became a prominent location along the Branch through industrial development and as a junction for other rail lines connecting with the mainline. The manufacture of glass and industry related to coal were the hallmarks of the area. During the late 1800s, additional rail lines were built creating a hub for the region. Roads such as the West Virginia Short Line, the West Virginia & Pittsburg, and the Fairmont, Shinnston, and Clarksburg Railway radiated from the mainline connecting the area to other rail lines and industry. All of these smaller lines funneled traffic to and from the main and were eventually absorbed into the B&O system.

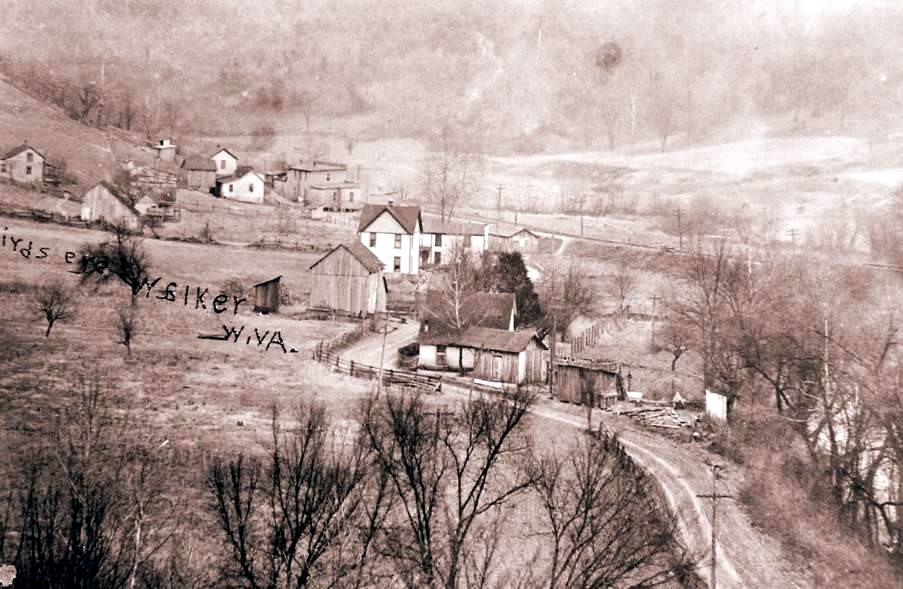

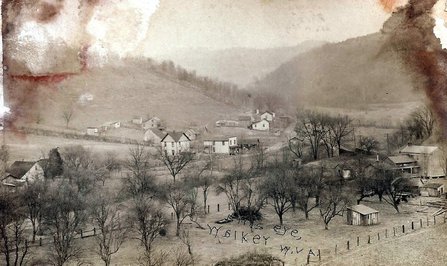

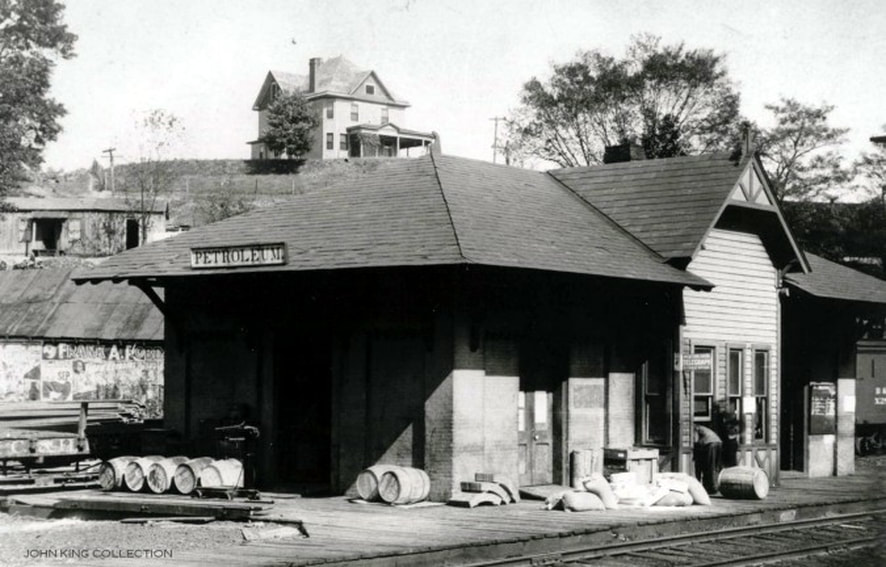

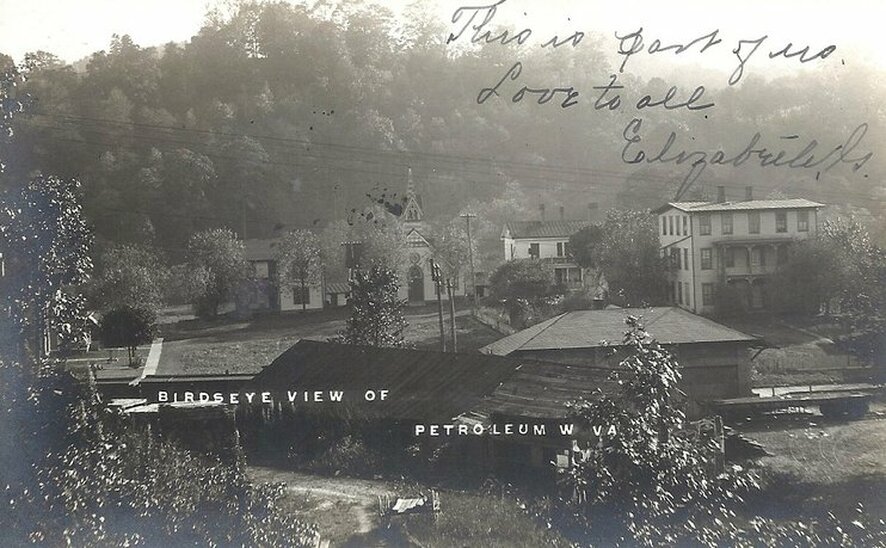

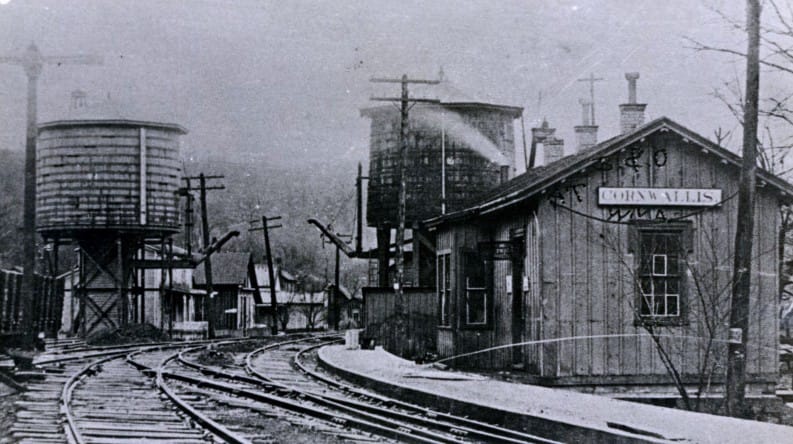

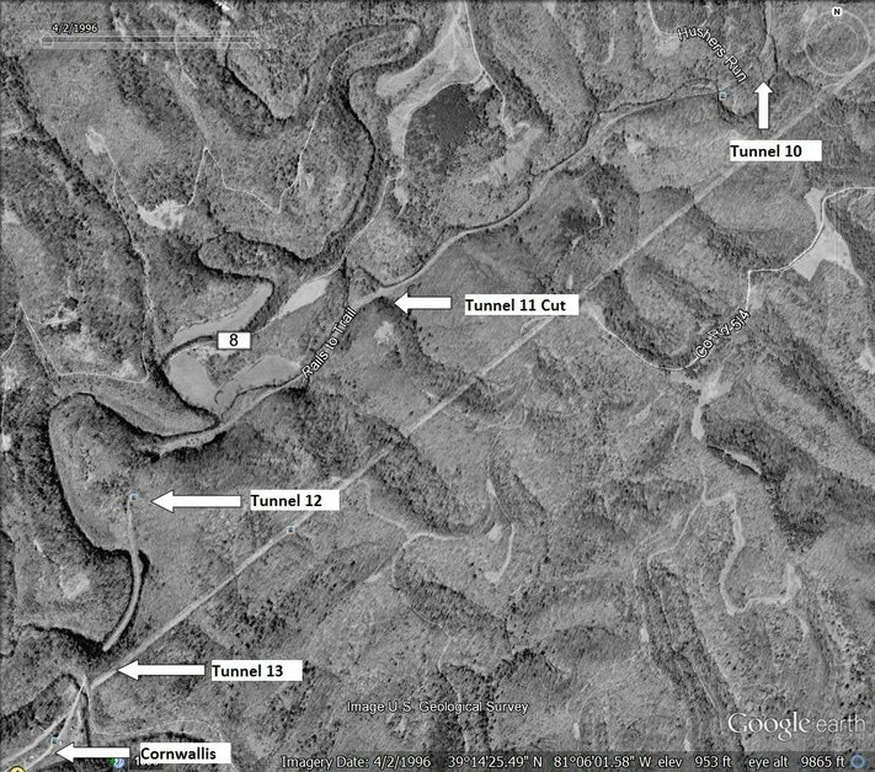

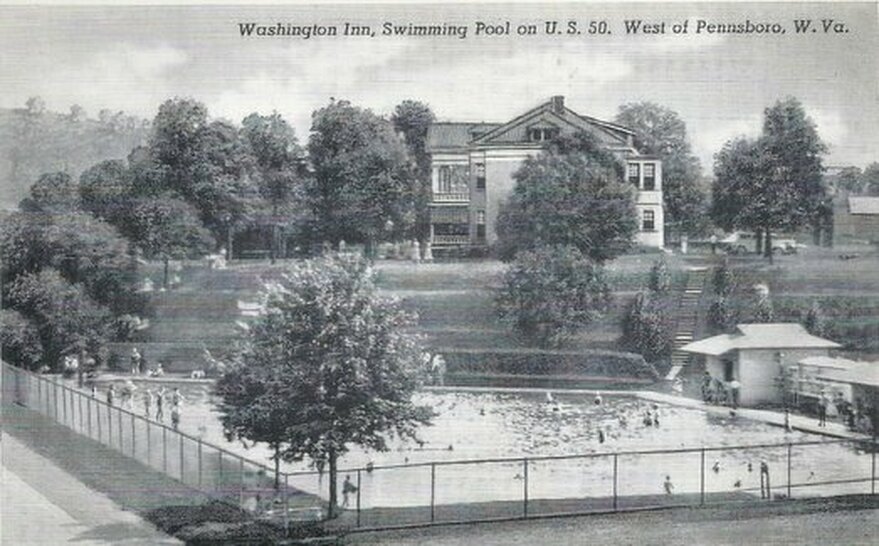

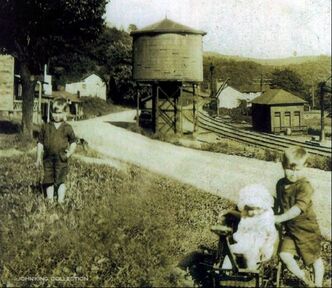

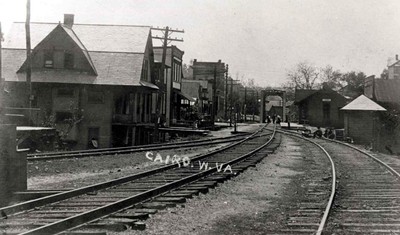

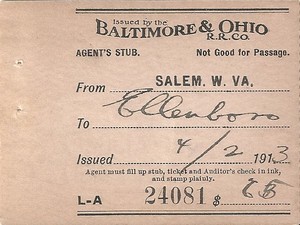

The Branch (mainline) between Parkersburg and Clarksburg was overwhelmingly rural with smaller towns and industry spread throughout its route. Communities such as Pennsboro, West Union, and Salem generated small amounts of rail traffic as did other locations along this sparsely populated section of railroad. Even smaller towns such as Cairo, Cornwallis, and Petroleum became junctions for tiny and relatively obscure short lines that all but vanished by the early 20th century. Most of the towns employed at bare minimum, a freight depot that furnished a means of shipping to the outside world. By the end of World War II, this on line freight scattered along the Branch had virtually disappeared. Never a major factor in the overall volume of freight that traveled the main, it was nevertheless a cited reason for the abandonment of the line in the 1980s.

The Branch (mainline) between Parkersburg and Clarksburg was overwhelmingly rural with smaller towns and industry spread throughout its route. Communities such as Pennsboro, West Union, and Salem generated small amounts of rail traffic as did other locations along this sparsely populated section of railroad. Even smaller towns such as Cairo, Cornwallis, and Petroleum became junctions for tiny and relatively obscure short lines that all but vanished by the early 20th century. Most of the towns employed at bare minimum, a freight depot that furnished a means of shipping to the outside world. By the end of World War II, this on line freight scattered along the Branch had virtually disappeared. Never a major factor in the overall volume of freight that traveled the main, it was nevertheless a cited reason for the abandonment of the line in the 1980s.

|

During the transition from the 1800s to 1900s, freight volumes continued to increase with the proliferation of mining and industry. This time period also coincided with the Gilded Era of the passenger train. The Parkersburg Branch, now fully integrated within the mainline connecting the East and Midwest, played host to numerous passenger trains of different classes. Long distance trains shared the route with secondary runs and added to this were the connecting trains from within the expanded B&O network and other roads. It was the golden age of rail travel and the Branch hummed with trains increasing the traffic total already laden with freight. The World War I years are often referred as the pinnacle in terms of traffic and existing number of route miles at a time when the rail network was at its peak. These halcyon years remained in earnest throughout the 1920s but by the time of the Great Depression, the rail scene was experiencing the beginnings of evanescence. Overall, certainly not unique to the Branch, however—this paragraph could be applicable to almost any railroad that existed at that time.

|

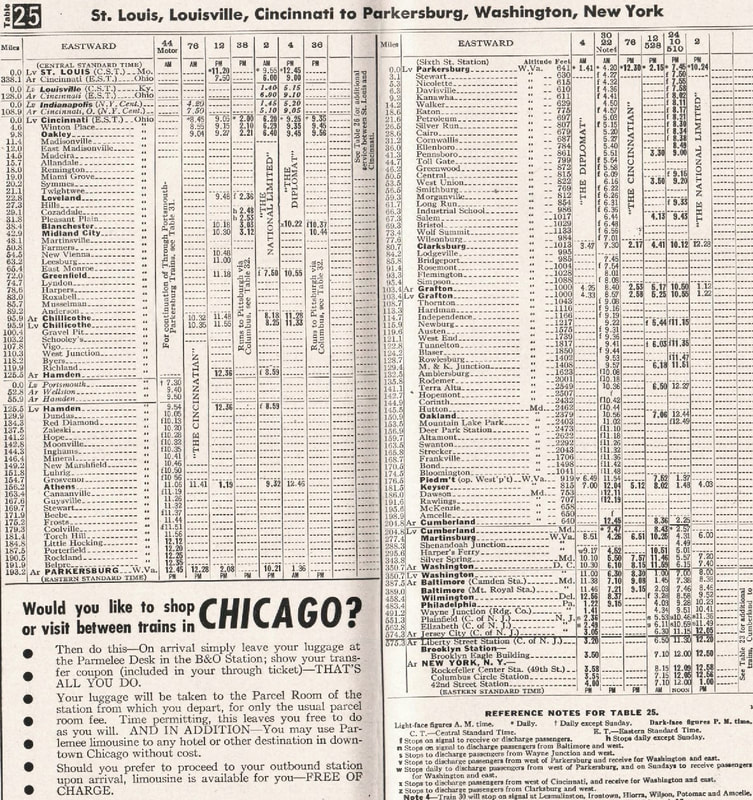

B&O published passenger timetable from 1948 listing the eastbound through trains that operated between New York and St. Louis

|

|

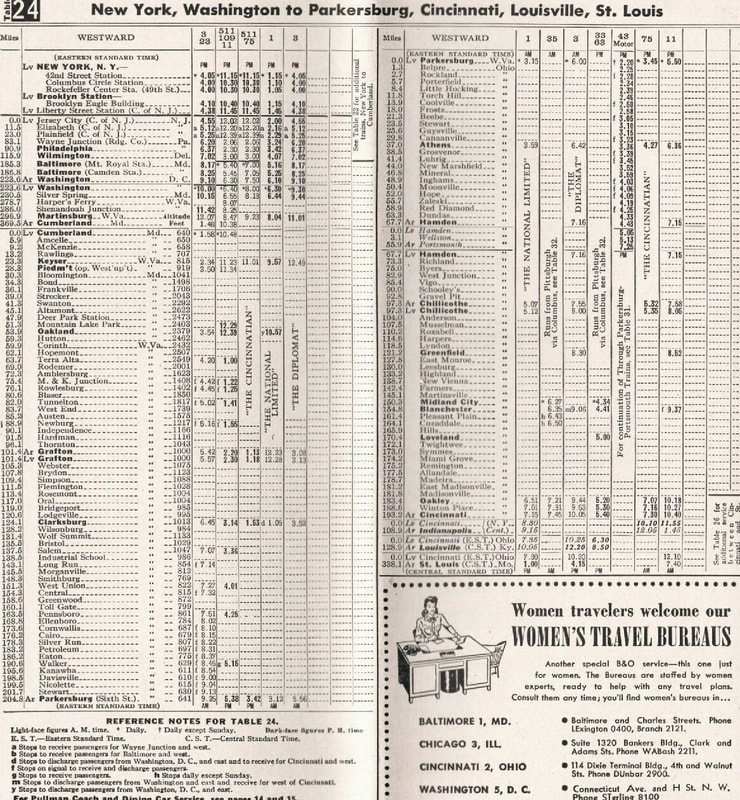

B&O published passenger timetable from 1948 listing the westbound through trains that operated between New York and St. Louis

|

Perhaps the first harbinger of the future was reflected in the decline of branch line passenger traffic that in turn, decreased numbers on mainline trains. The automobile was making inroads that affected short haul commuting and trucking did likewise to localized freight. Long distance freight and passenger trains were not directly affected as of yet due to a highway system that had not reached fruition. The major impact of the time though was reduced industrial output as a result of the Depression that did affect quantity. Industry took a hard hit in northern West Virginia during the 1930s as the demand for goods and raw material decreased. Firmly entrenched with manufacturing was the mining industry where lower demands and work strife were mitigating factors. Yet, in spite of the despair, this era is fondly recalled in rail history even if exaggeration rules the day. Better times lay ahead the B&O thought and along with other roads, an optimistic future of technological advances and the return of prosperity. By any measure, they were right and wrong. On the horizon was the 1940s and with it a global war that would change the landscape forever.

|

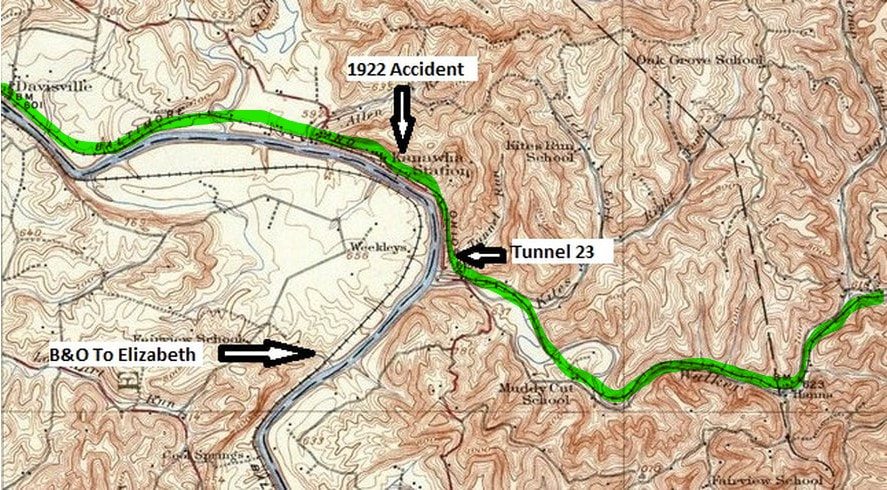

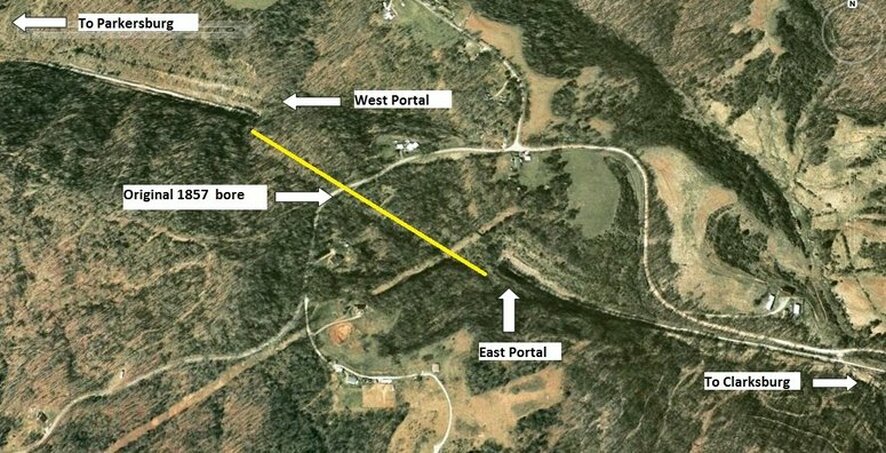

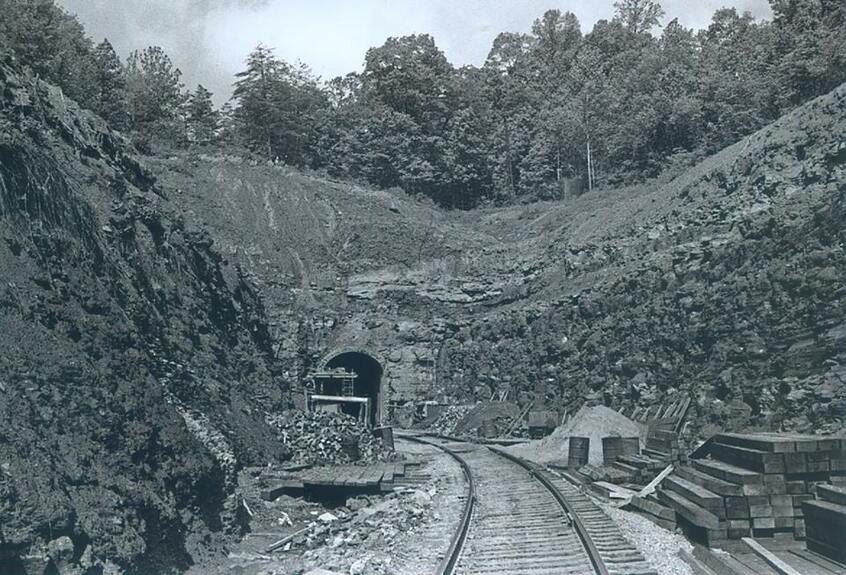

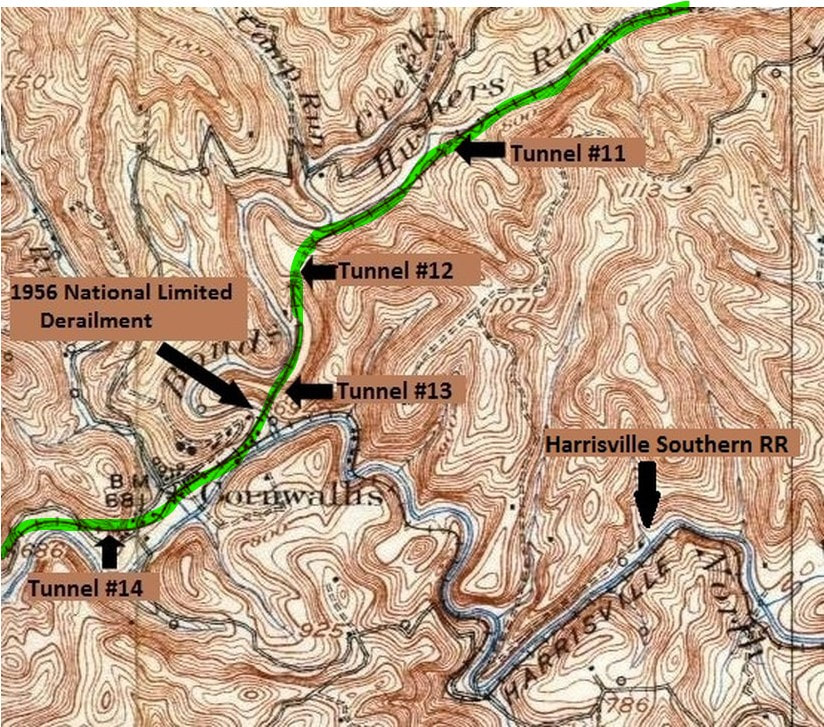

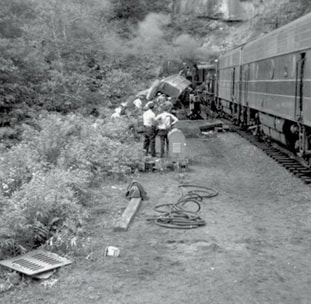

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Admiral Yamamoto said “I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant”. The giant was American industrial might and the lifeblood of that was the rail system. How quickly this country mobilized for war production is an incredible chapter in history and the railroad was integral in this conversion. At the outset of the war, eight scheduled QD freights traversed the Parkersburg Branch in addition to at least a dozen timetable passenger runs. This did not take into account the extra trains already running the line and the numbers swelled proportionately with troop movements, oil trains, and second sections of scheduled runs directly related to the war effort. The impact of the wartime traffic taxed the Parkersburg Branch to capacity on a single track mainline with passing sidings and block operators. Maintenance on the line was time sensitive due to traffic volume. Very little was done during the war years except what was vitally necessary which usually translated into the aftermath of a derailment. One project B&O was able to complete during this volatile time was to daylight the flood prone Tunnel 23 at Kanawha, the westernmost of the tunnels on the Branch, in 1943.

Once the war ended in 1945, traffic levels remained high as the country was beginning the process of demobilization. Passenger levels on the Branch ran high and trains such as the National Limited often ran in two sections to accommodate the volume. It was this immediate postwar traffic level that created a false optimism on the part of the B&O and other roads that this ridership would be sustained. Reflective of this spirit was the highly publicized launch of the Cincinnatian in 1947 in the hope that a daylight market Baltimore-Cincinnati train was viable. The trainset was a masterpiece in streamlined styling highlighted by four shrouded P7d class Pacifics as pooled power. At first excitement prevailed that the run would be a success---unfortunately, ridership peaked only at holiday periods. Ironically, due to the small capacity of the train, riders were turned away. The sad reality, however, that B&O soon realized it was a novelty and the swan song for the wartime levels. The public exodus from passenger rail had begun and the sparsely populated route of the Cincinnatian could not sustain a profitable operation. In 1950, the train was transferred to the Cincinnati-Detroit market where it fared much better. Symbolic of the changing times, decade of the 1950s would witness further contraction on a larger scale.

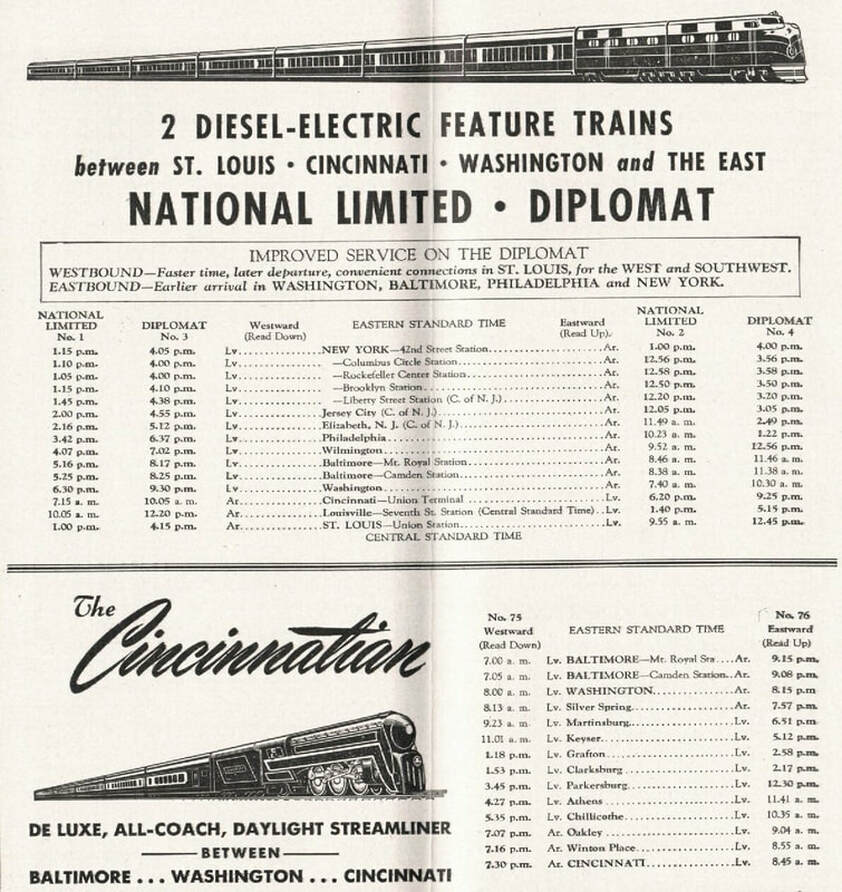

B&O, not unlike other major roads in the immediate postwar years, was optimistic about the future of passenger service. Ads such as these touting the National Limited, Diplomat, and the Cincinnatian reflected that hope. Sadly, it was short lived and by the 1950s, patronage had begun a rapid decline.

The 1950s signaled the true vanguard of change during the postwar era. B&O was transitioning from steam to diesel power and by 1958, this would be complete. Upgrades along the Parkersburg Branch had been forestalled during World War II and in 1951, Centralized Traffic Control (CTC) was finally implemented. Freight traffic remained steady on the line for most of the decade but rapid decline was occurring with passenger operations. Passenger trains on secondary and branch lines were systematically abolished due to loss of ridership to automobiles. Consequently, the transfer of patrons from these connecting lines to the Parkersburg Branch dwindled. The first long distance train casualty running the Branch was the Diplomat which ended service between Washington and Cincinnati in 1960. Over the road trucking in conjunction with highway development was making inroads and cutting into the freight business. By the end of the decade, B&O was suddenly in serious financial trouble and became the target of merger proposals by the 1960s.

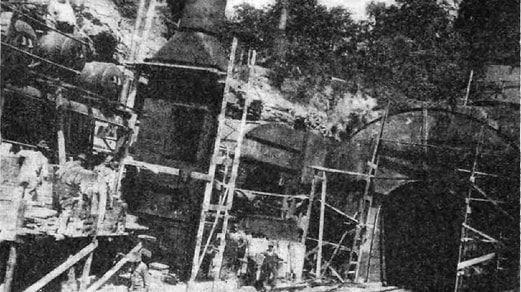

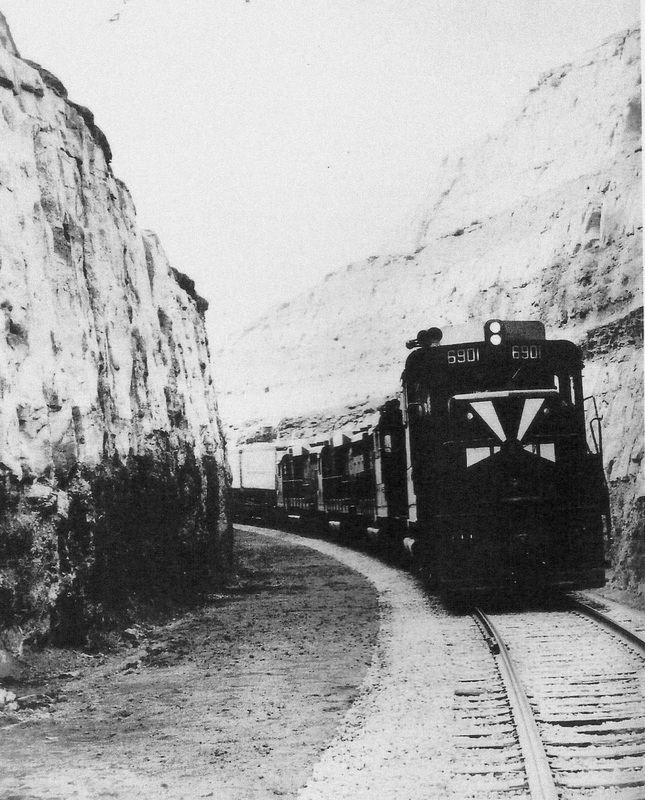

As the New York Central Railroad and the C&O Railway became the primary roads interested in acquiring B&O, the road was in dire straits. B&O stock values plummeted, and it was in desperate need of equipment. The ICC approved the acquisition of the B&O by C&O in 1963 although both retained the individual corporate identities. The financially robust C&O quickly began resuscitating B&O with equipment and funding for critical system improvements. In early 1963, B&O embarked on a tunnel clearance project on the Parkersburg Branch enabling the movement of larger freight cars and trailer on flat car (TOFC) trains. This opened the market to Cincinnati and St. Louis that was previously restricted for these movements.1965 was the last year of the National Limited in its full glory but it continued on for a few years longer as a stripped shell of its former self before fading into oblivion. The passenger train had finally succumbed to automobiles and the airline industry.

The early 1970s were to prove an eventful period. Passenger rail was nearing its end as operated by the B&O and the majority other roads. The Metropolitan would be the last train to traverse the Branch under the B&O flag. On May 1, 1971, Amtrak took over the operation of the national network and for the first time since 1857, no passengers would ride the rails between Parkersburg and Clarksburg because the route was initially excluded. By late 1971 and through political pressure exerted by Representative Harley Staggers, a train returned to the route aptly named the West Virginian. By 1972, this train had morphed into the Potomac Turbo notable if but for its design by United Airlines. Distinctly different from standard passenger equipment, it proved a failure as it was ill equipped to operate over the mountain grades east of Grafton. Plagued with operational problems, standard road power often was used to assist it before finally assigned on a permanent basis. The train was a victim of low ridership west of Martinsburg, WV and was discontinued in 1973. Amtrak tested the waters again in 1976 with a Washington-Cincinnati train named the Shenandoah which would remain on the Branch into the early 1980s.

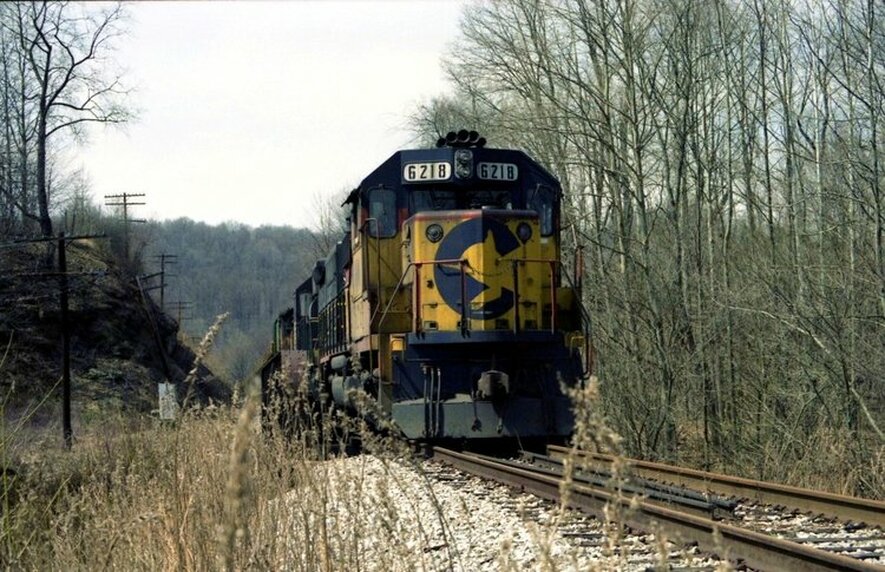

In 1971, there were still ten (10) scheduled through trains running the Parkersburg Branch. The total was evenly divided with five eastbound and five westbound entailing manifest and TOFC "jets". Ironically, this was the same number of scheduled timetable trains that existed at the outset of World War II. As was the pattern throughout its history, the total number of trains was higher with bulk (coal, grain, etc.) movements, second sections, and of course, local traffic. Unquestionably, the most significant development of the 1970s was the formation of the Chessie System in 1972 which combined the C&O, B&O, and Western Maryland into one operational entity. Each road retained its separate identity despite reorganizations and consolidations. Locomotives were painted in a colorful paint scheme sub lettered with the reporting mark of the owner. The Chessie System became the last face of the B&O not only on the Parkersburg Branch but elsewhere for the remainder of its operational existence.

As the New York Central Railroad and the C&O Railway became the primary roads interested in acquiring B&O, the road was in dire straits. B&O stock values plummeted, and it was in desperate need of equipment. The ICC approved the acquisition of the B&O by C&O in 1963 although both retained the individual corporate identities. The financially robust C&O quickly began resuscitating B&O with equipment and funding for critical system improvements. In early 1963, B&O embarked on a tunnel clearance project on the Parkersburg Branch enabling the movement of larger freight cars and trailer on flat car (TOFC) trains. This opened the market to Cincinnati and St. Louis that was previously restricted for these movements.1965 was the last year of the National Limited in its full glory but it continued on for a few years longer as a stripped shell of its former self before fading into oblivion. The passenger train had finally succumbed to automobiles and the airline industry.

The early 1970s were to prove an eventful period. Passenger rail was nearing its end as operated by the B&O and the majority other roads. The Metropolitan would be the last train to traverse the Branch under the B&O flag. On May 1, 1971, Amtrak took over the operation of the national network and for the first time since 1857, no passengers would ride the rails between Parkersburg and Clarksburg because the route was initially excluded. By late 1971 and through political pressure exerted by Representative Harley Staggers, a train returned to the route aptly named the West Virginian. By 1972, this train had morphed into the Potomac Turbo notable if but for its design by United Airlines. Distinctly different from standard passenger equipment, it proved a failure as it was ill equipped to operate over the mountain grades east of Grafton. Plagued with operational problems, standard road power often was used to assist it before finally assigned on a permanent basis. The train was a victim of low ridership west of Martinsburg, WV and was discontinued in 1973. Amtrak tested the waters again in 1976 with a Washington-Cincinnati train named the Shenandoah which would remain on the Branch into the early 1980s.

In 1971, there were still ten (10) scheduled through trains running the Parkersburg Branch. The total was evenly divided with five eastbound and five westbound entailing manifest and TOFC "jets". Ironically, this was the same number of scheduled timetable trains that existed at the outset of World War II. As was the pattern throughout its history, the total number of trains was higher with bulk (coal, grain, etc.) movements, second sections, and of course, local traffic. Unquestionably, the most significant development of the 1970s was the formation of the Chessie System in 1972 which combined the C&O, B&O, and Western Maryland into one operational entity. Each road retained its separate identity despite reorganizations and consolidations. Locomotives were painted in a colorful paint scheme sub lettered with the reporting mark of the owner. The Chessie System became the last face of the B&O not only on the Parkersburg Branch but elsewhere for the remainder of its operational existence.

Below is a list of daily scheduled manifest and TOFC trains that traversed the Parkersburg Branch on the B&O St. Louis main line as of September 1971:

Eastbound Westbound

Advance Manhattan (AMTN) Cincinnati Jet (CTNJ)

Manhattan (MHTN) St. Louisan (STLN)

Manhattan Trailer Jet (MHJT) Cincinnati 97 (CI97)

Cumberland 94 (CU94) Gateway 97 (GW97)

88 (St. Louis-Cumberland) St. Louis Trailer Jet (SLTJ)

Eastbound Westbound

Advance Manhattan (AMTN) Cincinnati Jet (CTNJ)

Manhattan (MHTN) St. Louisan (STLN)

Manhattan Trailer Jet (MHJT) Cincinnati 97 (CI97)

Cumberland 94 (CU94) Gateway 97 (GW97)

88 (St. Louis-Cumberland) St. Louis Trailer Jet (SLTJ)

The Parkersburg Branch began its final decade of existence with the formation of CSX Corporation in 1980. For the first half of the decade, CSX was a holding company for the Chessie System but the seed was planted for a mega merger with the Seaboard System. In 1986, the Chessie and Seaboard Systems were consolidated operationally into CSX Transportation. Meanwhile, during the early 1980s, six scheduled trains still ran the Branch in addition to extra movements. The Amtrak Shenandoah remained until 1981 when it was abolished because of low patronage. Thus ended passenger service forever on the Branch. Unforeseen was that freight traffic would soon follow suit.

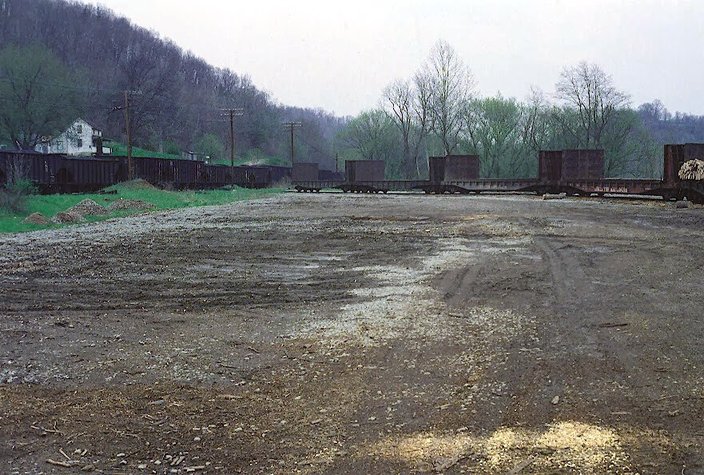

The line received intensive maintenance work and operationally, perhaps in the best condition it had been for years. Then in 1985, an announcement was made that stunned many in railroad circles. A decision had made to downgrade the St. Louis mainline between Cumberland and Cincinnati with scheduled trains rerouted and extra movements simply annulled. The final scheduled train to traverse the Parkersburg Branch was on August 31 ---however, an excursion and extra movements continued thereafter for a brief period. Eventually, all traffic ceased and CSX filed a petition with the ICC to officially abandon the route between Parkersburg and Clarksburg. The State of West Virginia legally challenged the action to no avail and CSX removed the track between Walker and Wolf Summit in 1988.

Shortly after the track removal in 1989, a group stepped in to preserve the railroad right of way for use as a recreational trail. This was the seedling for what would become the North Bend Rail Trail. During the mid 1990s, the track east of Parkersburg to Walker was removed when the sole remaining shipper relocated elsewhere. The stub from Clarksburg west to Wilsonburg was removed in 1999 when a coal operator ceased operations. What remained of the former Parkersburg Branch between Grafton and Clarksburg was christened as the Bridgeport Subdivision in CSX operations.

The new millennium has witnessed the development of the North Bend Rail Trail as among the finest and it is a popular attraction. In addition to recreational opportunities it offers for hikers and bikers, it indirectly generates revenue for the small communities it traverses. Although it has been almost three decades since the last train passed, the North Bend Rails to Trails Foundation and the regional historical societies have to their credit kept the history of the Parkersburg Branch alive as well.

The line received intensive maintenance work and operationally, perhaps in the best condition it had been for years. Then in 1985, an announcement was made that stunned many in railroad circles. A decision had made to downgrade the St. Louis mainline between Cumberland and Cincinnati with scheduled trains rerouted and extra movements simply annulled. The final scheduled train to traverse the Parkersburg Branch was on August 31 ---however, an excursion and extra movements continued thereafter for a brief period. Eventually, all traffic ceased and CSX filed a petition with the ICC to officially abandon the route between Parkersburg and Clarksburg. The State of West Virginia legally challenged the action to no avail and CSX removed the track between Walker and Wolf Summit in 1988.

Shortly after the track removal in 1989, a group stepped in to preserve the railroad right of way for use as a recreational trail. This was the seedling for what would become the North Bend Rail Trail. During the mid 1990s, the track east of Parkersburg to Walker was removed when the sole remaining shipper relocated elsewhere. The stub from Clarksburg west to Wilsonburg was removed in 1999 when a coal operator ceased operations. What remained of the former Parkersburg Branch between Grafton and Clarksburg was christened as the Bridgeport Subdivision in CSX operations.

The new millennium has witnessed the development of the North Bend Rail Trail as among the finest and it is a popular attraction. In addition to recreational opportunities it offers for hikers and bikers, it indirectly generates revenue for the small communities it traverses. Although it has been almost three decades since the last train passed, the North Bend Rails to Trails Foundation and the regional historical societies have to their credit kept the history of the Parkersburg Branch alive as well.

Operations

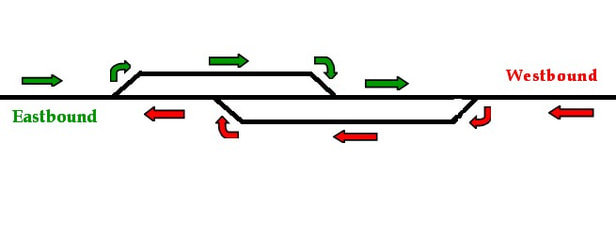

The Parkersburg Branch was predominately a single track main line populated with sidings at roughly 8-10 mile intervals during its peak. Except for a few standard passing sidings, the remaining were staggered or lapped sidings. These were constructed as two separate tracks on either side of the main with offsetting connecting points. In theory, these increased the operational length of the siding beyond the physical dimensions and were most effective with meets of opposing trains. Depending on the lengths of the meeting trains and if they could both utilize the sidings, a crafty dispatcher would route both trains through on a pass with neither requiring a stop.

B&O operating practice was predominately eastbound trains governed as priority. There were deviations depending on whether trains were on schedule or if a high priority westbound train was involved such as Train #1, the National Limited. For many years lasting into the early 20th century, train orders controlled the movements of trains with specific instructions to the point which a stop or meet was required. Signals began to appear on the Parkersburg Branch during the 1920s in the form of color position lights and these were used in conjunction by the block operators positioned along the route at passing sidings. Depending on the signal indications, the operators would align the switches on the main or sidings according to instructions from a dispatcher.

B&O operating practice was predominately eastbound trains governed as priority. There were deviations depending on whether trains were on schedule or if a high priority westbound train was involved such as Train #1, the National Limited. For many years lasting into the early 20th century, train orders controlled the movements of trains with specific instructions to the point which a stop or meet was required. Signals began to appear on the Parkersburg Branch during the 1920s in the form of color position lights and these were used in conjunction by the block operators positioned along the route at passing sidings. Depending on the signal indications, the operators would align the switches on the main or sidings according to instructions from a dispatcher.

|

Distinctive B&O color position lights displaying proceed, approach, and stop indications. These signals populated the Parkersburg Branch as with other locations along B&O main lines.

These iconic signals have rapidly disappeared except for a few remaining locations as CSXT continues to standardize its system with a more modern---and generic--- type. Images Dan Robie 2009 and Matt Robie 2014 |

B&O had planned a conversion to CTC (Centralized Traffic Control) during the 1940s but World War II postponed its implementation for another decade. Although CTC would improve the efficiency of the railroad, it was a job killer. The block stations located between Parkersburg and Clarksburg were eliminated and replaced by a single dispatcher at Grafton by 1951. This dispatcher viewed a board with a track diagram for the Parkersburg Branch and from a desk controlled the passing siding switches and signals along the route remotely. CTC did not totally eliminate train orders---OB Tower at Parkersburg and MD Tower at Clarksburg remained as train order points into the Chessie System era.

The theory and practice of routing meeting trains through a lap siding. A coordinated move with train lengths, speed, and the proficiency of the block operator or dispatcher as factors.

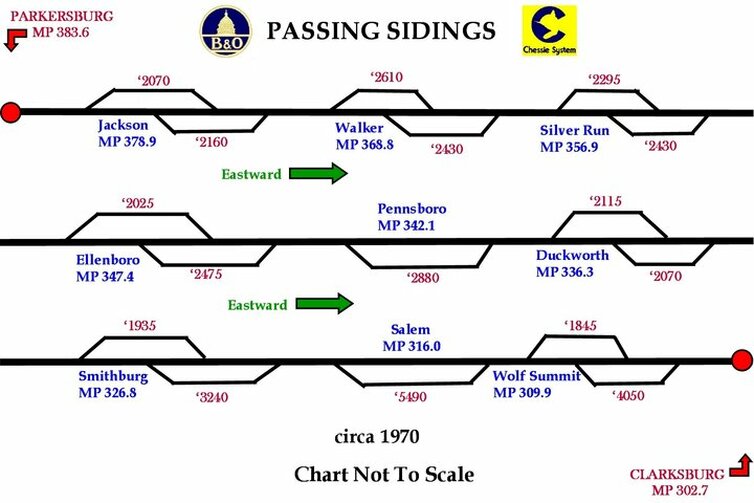

The chart below depicts the sidings as they are noted in the 1970 B&O timetable. During the intervening years between World War II and 1970, other sidings existed and were either eliminated or modified. A lapped siding at Cornwallis was taken out of service as were conventional sidings at Long Run and Petroleum. The lap siding at Salem was converted to a longer conventional single siding. Wilsonburg was also a lap siding but was converted to a storage siding in later years.

A block chart depicting the passing sidings located between Parkersburg and Clarksburg as they existed in 1970. Elimination and modification at a few locations since the 1940s had occurred. Sidings on the chart are exaggerated for clarity and the lengths are calculated capacity.

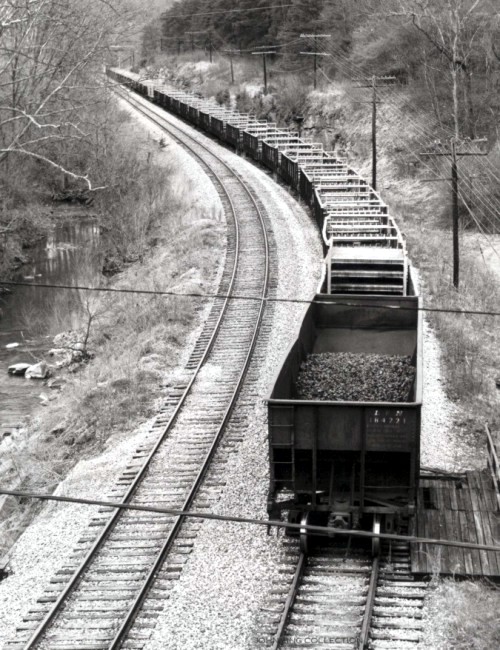

For a railroad spanning the breadth of northern West Virginia, the Parkersburg Branch is not generally associated with the movement of coal trains although this type of traffic did traverse the route. Instead, it was the road of priority manifest trains moving east and west and of course, passenger trains great and small. This remained as the traffic pattern until the 1950s when the passenger trains began disappearing from the timetables. From the mid 1960s to the closing of the line in 1985, manifest prevailed but the association changed to that of the route of the trailer (TOFC) trains.

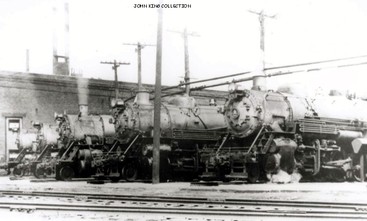

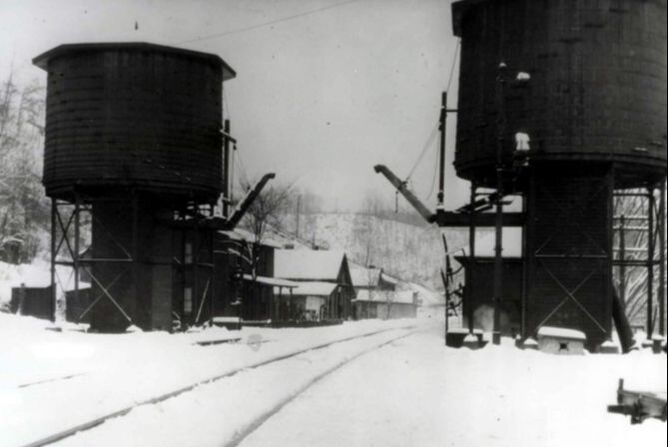

Throughout the history of the Parkersburg Branch, the motive power ran the gamut as the steam locomotive progressed in development. Of note was that the largest and most powerful of steam locomotives were not necessarily assigned to the line. Power such as 4-8-2 Mountains and articulated models such as EM1 2-8-8-4s were not regular Branch visitors. The mainstays on the line were the 2-8-0 Consolidations and 2-8-2 Mikados (MacArthurs during World War II) in freight service with various classes of 4-6-2 Pacifics pulling the passenger varnish. Complete steam servicing facilities were located at Parkersburg and Clarksburg with water stops at Petroleum, Cornwallis, Central Station, and Rock Run near Smithburg in between. The stop at Central Station was gone by the World War II era.

Throughout the history of the Parkersburg Branch, the motive power ran the gamut as the steam locomotive progressed in development. Of note was that the largest and most powerful of steam locomotives were not necessarily assigned to the line. Power such as 4-8-2 Mountains and articulated models such as EM1 2-8-8-4s were not regular Branch visitors. The mainstays on the line were the 2-8-0 Consolidations and 2-8-2 Mikados (MacArthurs during World War II) in freight service with various classes of 4-6-2 Pacifics pulling the passenger varnish. Complete steam servicing facilities were located at Parkersburg and Clarksburg with water stops at Petroleum, Cornwallis, Central Station, and Rock Run near Smithburg in between. The stop at Central Station was gone by the World War II era.

Train #76, The Cincinnatian, moves east through Belpre, OH in June 1947 soon to cross the Ohio River and enter Parkersburg. This train was introduced in January 1947 with great fanfare but within three years, it was discontinued between Baltimore and Cincinnati due to low ridership. Although short lived, a beloved train if for no other reason than appearance sake. A beautiful trainset powered by four magnificently streamlined P7d Pacifics in gleaming Royal blue. Image Richard J. Cook/Allen County Museum

The early diesel era was exemplified by EMD E units in passenger service and F units for freight during the transition from steam. By the early 1950s, EMD four axle (GP series) hood units entered the scene and became the backbone of the B&O fleet lasting through the Chessie System era into the formation of CSX. Six-axle EMD power such as the SD35, SD40, and SD50 traversed the Branch but these units were typically used as helpers on the West End grades east of Grafton. The Branch also hosted models by Alco and Baldwin although in most instances, these were smaller locomotives used in yard and local branch line service. Grades along the Parkersburg Branch were a lesser issue in the diesel era since multiple units could be lashed together to match the tonnage.

The Parkersburg Branch was the artery for the B&O Monongah Division. Connecting with the mainline were numerous secondary and branch lines that funneled coal from mines scattered across northern and central West Virginia. Though the vast volume of this tonnage moved east via Grafton and the West End, a considerable amount also moved westward over the Branch. This was also an area deeply associated with the oil and gas industry in addition to glass manufacturing. Manifest traffic of various sorts was prevalent as well especially in the era predating the Interstate Highway system. As one would expect, Parkersburg and Clarksburg were the hubs for this concentration of industry with sporadic shippers scattered along the Branch. Longer distance trains contained blocks of cars for Parkersburg and Clarksburg with locals distributing cars to and from these points.

The Parkersburg Branch was the artery for the B&O Monongah Division. Connecting with the mainline were numerous secondary and branch lines that funneled coal from mines scattered across northern and central West Virginia. Though the vast volume of this tonnage moved east via Grafton and the West End, a considerable amount also moved westward over the Branch. This was also an area deeply associated with the oil and gas industry in addition to glass manufacturing. Manifest traffic of various sorts was prevalent as well especially in the era predating the Interstate Highway system. As one would expect, Parkersburg and Clarksburg were the hubs for this concentration of industry with sporadic shippers scattered along the Branch. Longer distance trains contained blocks of cars for Parkersburg and Clarksburg with locals distributing cars to and from these points.

The two premier passenger trains to traverse the Parkersburg Branch were the National Limited and the Diplomat. Throughout most of their careers, these trains--both eastbound and westbound--passed between Parkersburg and Clarksburg during the night which explains the dearth of photos on the Monongah Division. Pictured here in different locales are, left, the eastbound National Limited Train #2 departing St. Louis in 1940. At right is Train #4, the Diplomat, passing through Vincennes, IN in 1950. Both images Otto Perry-Denver Western Library.

Grades

The Branch grades do not compare with ones east

of Grafton but it was hardly a flat piece of railroad between Parkersburg and

Clarksburg. Grades at a few locations

did exceed 1% which is not stiff but certainly a respectable climb and explains

the practice of doubleheading power during the steam era to maintain trains at

speed. The grades still faced diesels but additional units could easily be

added to accommodate the tonnage. Eastbound trains overwhelmingly faced more of

the ascending grades and conversely, westbounds drifted down more descending

ones.

The toughest stretch of railroad traversed by both was the region between Cairo and Walker. It was a climb to Silver Run from either direction just as it was a climb from Petroleum in either direction. The longest continuous climb was for eastbounds from West Union to Wolf Summit with the ascent between Long Run and Industrial the steepest section. Eastbounds also faced noteworthy ascents from Walker to Eaton and Cornwallis to Ellenboro. The toughest span for westbounds was Cairo to Tunnel #21 at Eaton and Wilsonburg to Wolf Summit. Extremes in elevation above sea level ranged from Parkersburg at 614 feet to Wolf Summit at 1119 feet----505 feet of difference.

The toughest stretch of railroad traversed by both was the region between Cairo and Walker. It was a climb to Silver Run from either direction just as it was a climb from Petroleum in either direction. The longest continuous climb was for eastbounds from West Union to Wolf Summit with the ascent between Long Run and Industrial the steepest section. Eastbounds also faced noteworthy ascents from Walker to Eaton and Cornwallis to Ellenboro. The toughest span for westbounds was Cairo to Tunnel #21 at Eaton and Wilsonburg to Wolf Summit. Extremes in elevation above sea level ranged from Parkersburg at 614 feet to Wolf Summit at 1119 feet----505 feet of difference.

Connecting Lines

As the B&O corridor through the Monongah Division, the Parkersburg Branch was the funnel connecting points east and west as a sector of the St. Louis main line. During the peak years of operation, a spider web of secondary and branch lines radiated from the mainline at various points along the 80 mile stretch between Parkersburg and Clarksburg. Beginning at Parkersburg, a connection to the Ohio River Line which spanned the valley between Kenova and Wheeling. Also, a B&O branch--originally the Little Kanawha Railroad-- extended to Elizabeth paralleling the Little Kanawha River into Wirt County. This line was eventually abandoned excepting for a small remnant at Parkersburg that became the short line Little Kanawha River Railroad. Although across the river in Ohio, Belpre was the western boundary of the Monongah Division and a connection to the former Marietta and Cincinnati Railroad.

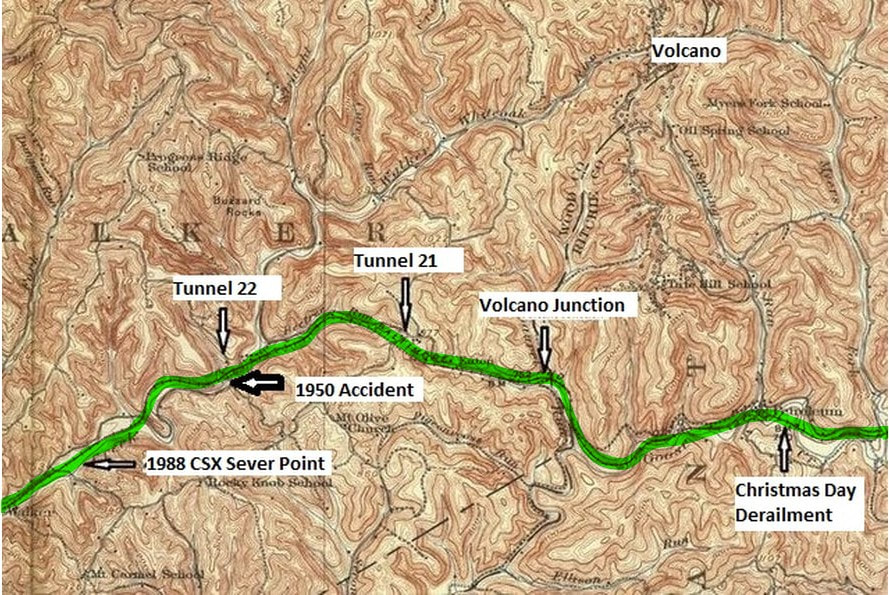

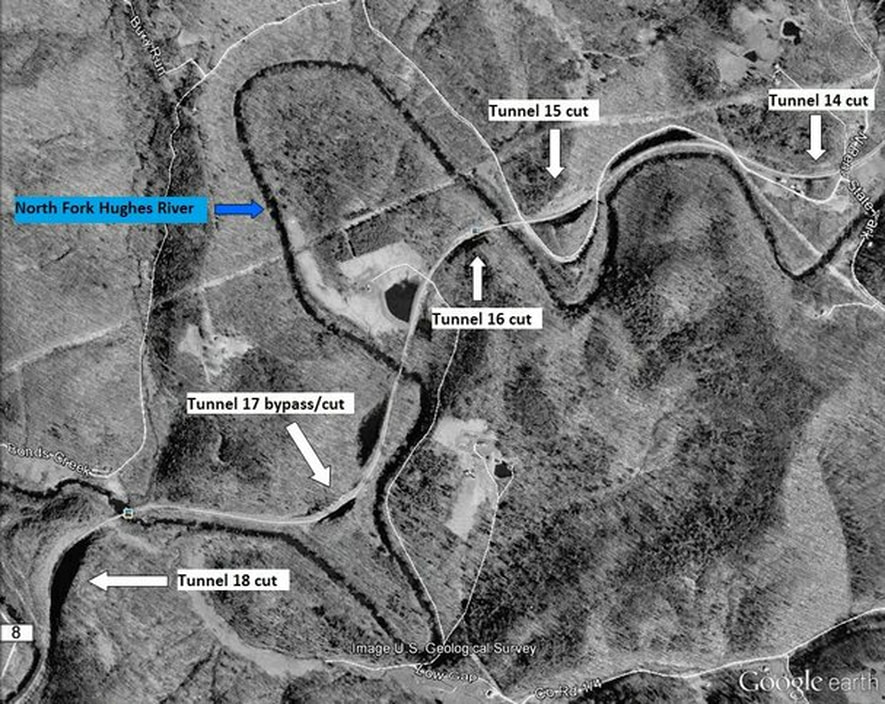

Small short lines that connected with the Parkersburg Branch include the Laurel Fork & Sand Hill, a small railroad constructed from the B&O at Petroleum to the town of Volcano during the great oil boom. Continuing east, the Cairo and Kanawha Railroad extended from its connection with the B&O at Cairo to McFarlen situated along the South Fork Hughes River. The Harrisville Southern interchanged with the B&O at Cornwallis and terminated at the Ritchie County seat of Harrisville. A narrow gauge line (P&H) once traversed the countryside from Pennsboro to Harrisville and later extended beyond. These small lines faced extinction by the early 20th century and were relegated to memory.

Clarksburg was a quintessential B&O town with secondary lines intersecting with the Parkersburg Branch. The Short Line connected with the main at the west side of town and extended to New Martinsville where it connected to the Ohio River Line. Another B&O line---the MR -- ran from Clarksburg through Haywood and continuing to Fairmont. Extending south from town was a former West Virginia & Pittsburgh route to Weston that was ultimately acquired by the B&O.

Small short lines that connected with the Parkersburg Branch include the Laurel Fork & Sand Hill, a small railroad constructed from the B&O at Petroleum to the town of Volcano during the great oil boom. Continuing east, the Cairo and Kanawha Railroad extended from its connection with the B&O at Cairo to McFarlen situated along the South Fork Hughes River. The Harrisville Southern interchanged with the B&O at Cornwallis and terminated at the Ritchie County seat of Harrisville. A narrow gauge line (P&H) once traversed the countryside from Pennsboro to Harrisville and later extended beyond. These small lines faced extinction by the early 20th century and were relegated to memory.

Clarksburg was a quintessential B&O town with secondary lines intersecting with the Parkersburg Branch. The Short Line connected with the main at the west side of town and extended to New Martinsville where it connected to the Ohio River Line. Another B&O line---the MR -- ran from Clarksburg through Haywood and continuing to Fairmont. Extending south from town was a former West Virginia & Pittsburgh route to Weston that was ultimately acquired by the B&O.

Parkersburg

This 1904 topo map provides a look at the railroad layout in the Parkersburg vicinity at its peak. The Parkersburg Branch (green) enters town from the east along the Little Kanawha River and crosses the Ohio as a continuation of the mainline to Cincinnati. The Ohio River Railroad (B&O-red) parallels its namesake as a route between Wheeling and Kenova. Both the High and Low Yards are active and the Little Kanawha Railroad (B&O-purple) occupies the south bank of the stream for which it is named as a route to Elizabeth. Also across the river in Ohio, the B&O line to Marietta (yellow) diverges from the main at Belpre.

Even as B&O was constructing its route from Grafton to Wheeling, the company had its eyes on Parkersburg as an eventual launching point for westward expansion. In fact, as early as 1842, a rail line to Parkersburg was considered the long term primary objective instead of Wheeling. The reasons for this were twofold; first, a railroad to Parkersburg offered a more direct route across Ohio to Cincinnati and eventually, St. Louis. Second, in an era before locks and dams were built on the Ohio River, Parkersburg offered better stability in water levels because it was farther downstream. This was a critical factor in the years before a bridge was built as freight and passengers were transferred by water from the West Virginia side to the Marietta and Cincinnati Railroad connection at Marietta, OH. Once a bridge across the river from Parkersburg to Belpre was completed in 1871, the river became a moot factor. An engineering masterpiece upon its completion, it was the longest bridge of its type in the world for several years. The stone used for its piers was quarried in the West Union area.

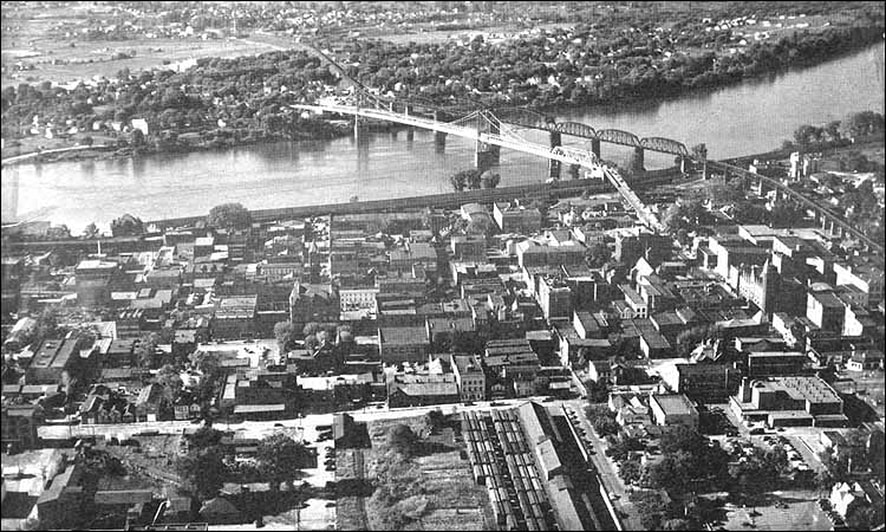

A look at the Parkersburg riverfront frozen in time as it was 1952. The aerial image places into context the expanse of the B&O Ohio River bridge. Adjacent to it is the 5th Street suspension bridge and the flood wall can be seen below both. Note the boxcars at the terminal in the foreground. Readers familiar with Parkersburg can spot what still exists in this image as well as what vanished from the wrecking ball. Image courtesy Parkersburg WV-A Vintage portrait.

The Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike had been completed a short two decades once the rails of the Northwestern Virginia Railroad reached Parkersburg in 1857. As a superior means of travel, the railroad was the choice for commercial movements of freight and passengers west of Grafton. During the Civil War years and through Reconstruction, the Parkersburg Branch and connection continuing into Ohio was a rail monopoly within the area until the construction of the Ohio River Railroad in the 1880s. This line paralleled the Ohio River between Wheeling and Kenova providing north and south rail service as it intersected the east west route at Parkersburg. Commerce flourished along the ORR in the river valley and this line was ultimately absorbed into the B&O in 1912 creating a prosperous rail region exclusive to the road. The 1890s witnessed the construction of the Little Kanawha Railroad which paralleled the namesake stream along its south bank to Elizabeth in Wirt County. This line, too, fell under full B&O ownership during the 1930s.

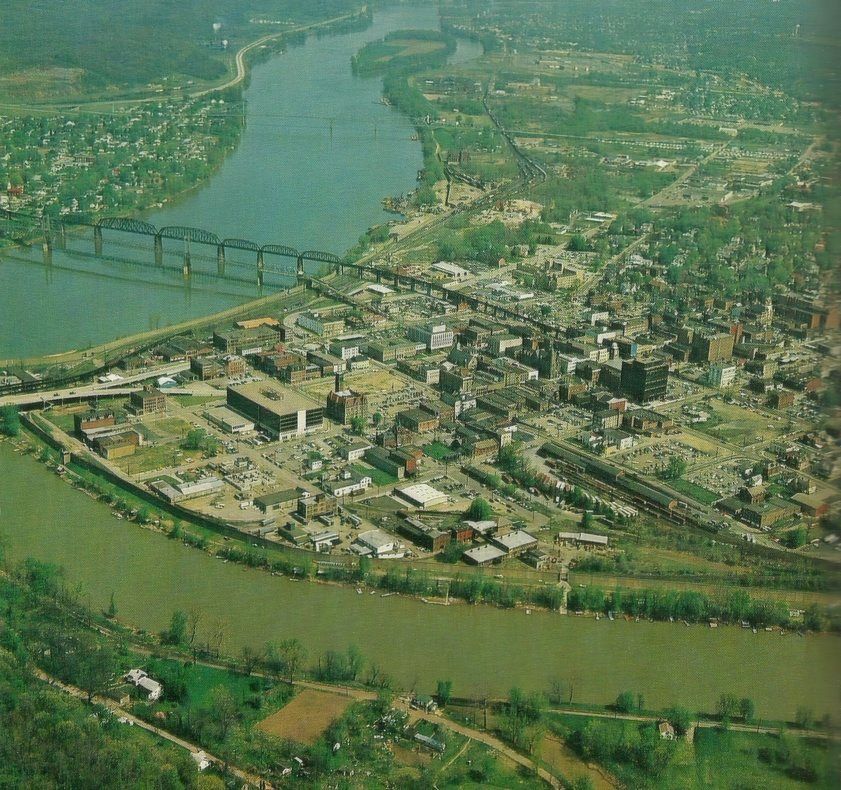

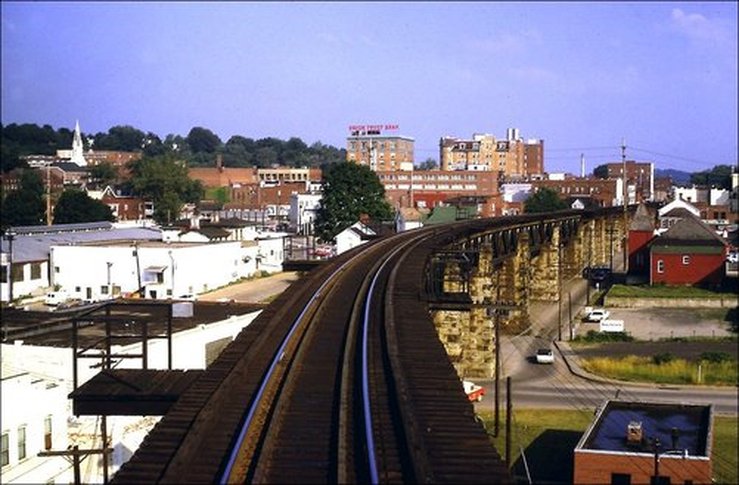

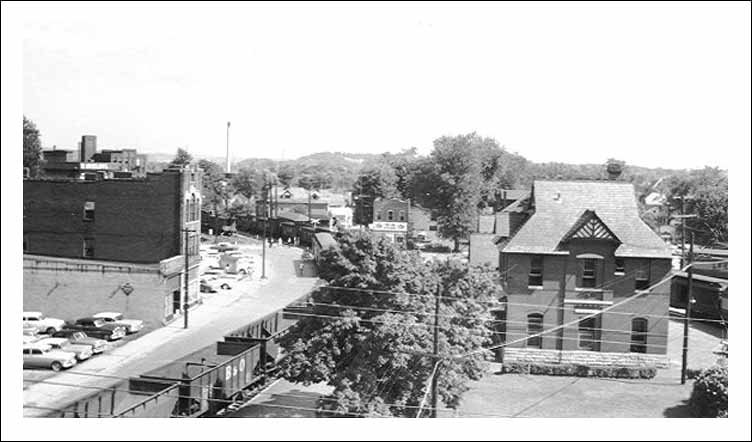

Set the dial on a time machine for Parkersburg circa 1974 and this is the result. In addition to the Ohio River bridge, the downtown freight terminal and the Low Yard along the river leave an impression time stamped in this image. Parkersburg was still a B&O crossroads for not only East-Midwest traffic but also Wheeling and Pittsburgh freight on the Ohio River line. Photo by Arnout Hyde, Jr. /courtesy Teresa Hyde

Parkersburg became the epicenter of a region that experienced a great oil and gas boom from the late 19th century into the early 1900s. To the north along the Ohio River was the Sistersville region and extending east an area bordering the Little Kanawha River at Elizabeth. Another sector east of Parkersburg lay directly on the route of the railroad at Petroleum and Cairo. Earlier oil and gas booms located at Burning Springs prior to the Civil War and at Volcano immediately afterward contributed substantially to the growth of the area.

Ohio River Bridge

A late 1800s view taken from what is present day looking upstream along the Ohio. The 1871 bridge presents a solitary appearance as the only span crossing the Ohio River at this date. In the foreground is the original Ohio River Railroad bridge spanning the Little Kanawha River at its mouth. Both bridges look fragile and would ultimately be replaced as steam locomotives became larger and heavier. Dan Robie/John G. King collection

|

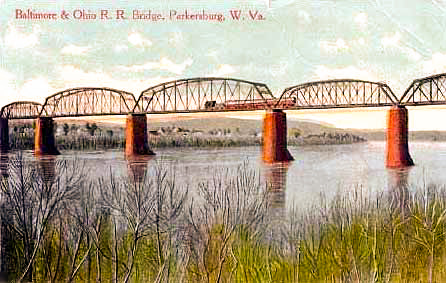

Early 20th century postcard with a train crossing the bridge. The new truss spans are in evidence dating this rendition to no earlier than 1905. Image courtesy Parkersburg WV-A Vintage Portrait

|

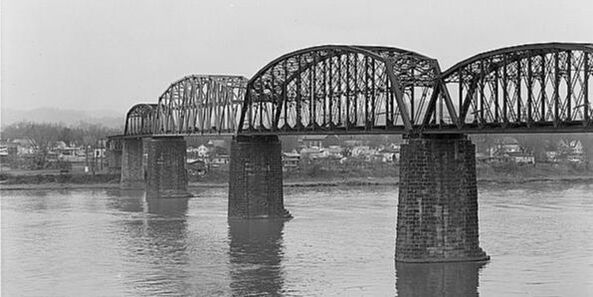

This 1973 photo clearly shows the silver truss span that was replaced after a barge struck a pier and exploded. The accident occurred in January 1972 and not only damaged the river bridges but buildings in Parkersburg and Belpre. Tragically, eleven persons were injured and two were killed. Photo William E. Barrett/Library of Congress

|

The Ohio River Bridge was replaced in two phases. First were the approaches built upon the original piers on both the Parkersburg and Belpre sides completed by 1900. This was followed by heavier truss spans over the river completed by 1905. Upgrading the bridge was a necessity due to steam locomotive development resulting in larger and heavier models. No significant modifications were done until 1972 when a barge struck a pier and exploded. As a result, an entire truss span was replaced with the bridge closed to traffic until repairs were completed.

|

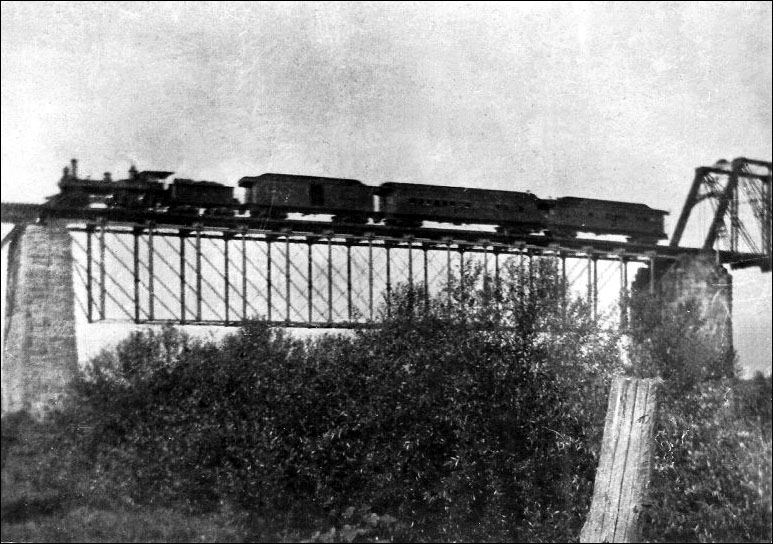

Early B&O passenger train crosses the bridge in a photo that is perhaps circa 1875. The completion of the Ohio River bridge accelerated the westward expansion of the road. Image courtesy of Parkersburg WV-A Vintage Portrait

|

A 1967 view looking east into town from the Parkersburg bridge approach. An impressive bridge by any measure and the deep blue luster on the rail heads indicative of heavy train traffic. Image courtesy Parkersburg WV-A Vintage Portrait

|

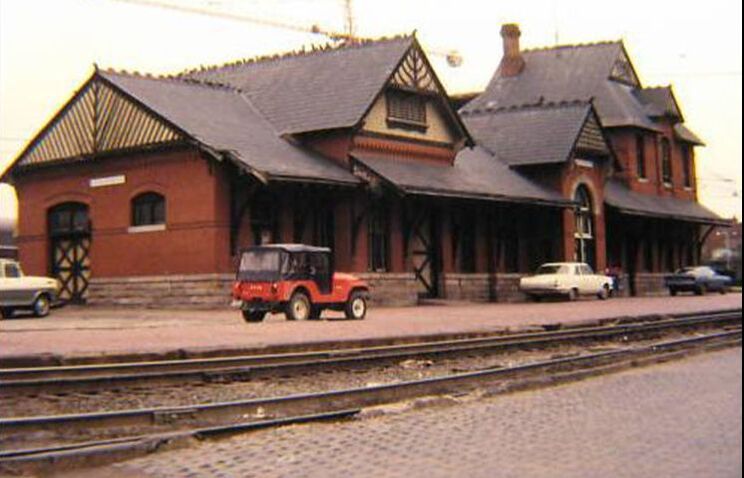

The primary B&O Parkersburg passenger station was located just east of the Ohio River bridge on the block bounded by Green and Avery Streets. Constructed in 1883 of Victorian design, this brick structure hosted thousands of passengers traveling east and west for nearly ninety years. As with many stations across the country, once passenger rail declined these structures were neglected often falling into disrepair before facing demolition. The B&O station was razed in 1973 in an era before preservation efforts gained favor. When Amtrak service returned to the city from 1976-1981, a small “Amshack” trailer was used for passengers. Parkersburg was a major stop for the B&O on the St. Louis mainline despite its mid-sized city status in regards to population. All of the long distance trains called as well as the secondary ones. On a route that was sparsely populated, B&O needed passenger base wherever it could be found. The other station in Parkersburg at Ann Street served the Ohio River line and this structure will be included in a future piece about the Ohio River line.

Crew change completed, the St. Louis Trailer Train heads across the Ohio River bridge in this circa 1980 photo. This TOFC (trailer on flatcar) hotshot will continue its trip across Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois until terminating at Cone Yard in East St. Louis. Image Karl Underwood/Todd M. Atkinson collection

|

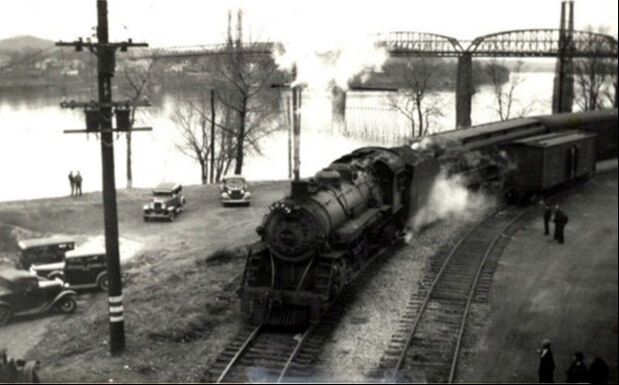

P3 Pacific #5100 runs the transfer track along the Ohio River near the mouth of the Little Kanawha. This is the connection between the B&O mainline and the Ohio River Line. The automobiles date this image circa 1930s. Dan Robie/John G. King collection

|

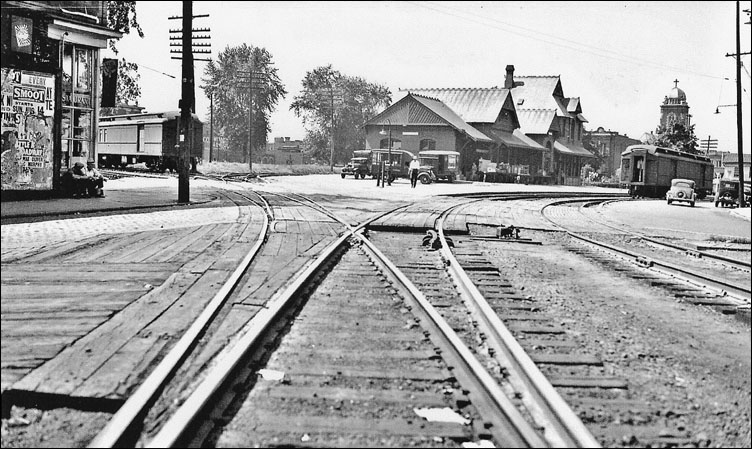

A westbound view of the B&O station circa 1930s. The photographer obviously stood on the mainline track and framed this scene rather nicely. This curve at the station was among the sharpest on the route. Image courtesy Parkersburg WV-A Vintage Portrait

|

|

Activity abounds with Train #76, the Cincinnatian, stopped at Parkersburg for both passengers and a crew change. The engineer is climbing aboard the streamlined P7d Pacific #5304 for the trip east over the Parkersburg Branch to Grafton. This classic scene, circa 1948, captures an era that would end all too soon. Image courtesy Adam Burns collection

|

A 1950s view looking eastward at the B&O station. The photographer gets bonus points for including the train of coal empties probably moving eastbound to a mine somewhere on the Monongah Division. Image courtesy Parkersburg WV-A Vintage Portrait

|

Steam was in its twilight when this June 1956 photo of Train #23, the West Virginian, captured its arrival at Parkersburg. Although lacking the stature of the National Limited and Diplomat, this train filled the niche of serving all the whistle stop communities along its route. Photo Richard J. Cook/courtesy Allen County Museum All rights reserved.

|

The B&O station in its twilight circa late 1960s. Few passengers (or trains) remained by this date as the glory years had long since passed. Not preserved as a landmark, the structure vanished beneath the bulldozer tread in 1973. Image courtesy Parkersburg WV-A Vintage Portrait.

|

Train time during the late 1970s at Parkersburg. The eastbound Shenandoah is stopped and it looks like a handful passengers await. Note the "Amshack" trailer used in lieu of the now gone B&O station. Dan Robie/John King collection

|

|

The date is May 5, 1973 and although the E8 is painted for the B&O, it is now the era of Amtrak. A rather leisurely scene at the station platform as the Potomac Special awaits its eastbound departure. Image courtesy Parkersburg WV-A Vintage Portrait.

|

Amtrak FP40HR #266 has stopped at Parkersburg with Train #32, the Shenandoah, in this 1980 scene. At right a westbound train led by B&O GP40-2 #4127 waits to depart. Image Karl Underwood/ Todd M. Atkinson collection

|

The center of Parkersburg operations along the mainline was the “High Yard". Consisting of more than 36,000 feet of storage capacity, this was the primary classification point for inbound and outbound freight cars both to points east and west and for the industrial base in the Parkersburg area. In its prime, the yard was complete with a roundhouse and turntable during steam era operations but still remained in use with the onset of diesels. A transfer track diverged from the high yard for trains to connect with the Ohio River line and "Low Yard". Always an integral connection between the two B&O lines, the transfer track took on extra significance during the 1963 tunnel project between Parkersburg and Clarksburg. Rerouted trains over the Short Line and Ohio River line used this track to reenter the mainline to proceed westward through Ohio. Eastbound trains did likewise except in reverse order.

|

This was the treasured scene that awaited a visitor at the Parkersburg radial in 1950. Q Class Mikados ready for duty on The Branch and elsewhere on the Monongah, Wheeling, and Ohio Divisions. Dan Robie/ John G. King collection

|

GP30 #6964 and a mate at Parkersburg in 1970. This is a "hybrid" locomotive in that it shares a mid 1960s Gothic lettering scheme with the "Sunburst" conspicuity lines on the side. Not uncommon during this era. Dan Robie/ John G. King collection

|

Chessie cats at the roundhouse service area in 1983. The Parkersburg terminal provided supplemental power for mainline trains in addition to local and yard jobs. Image courtesy Dave Dupler.

When the St. Louis mainline was downgraded and the Parkersburg Branch severed, the High Yard in effect became the secondary yard. Since through trains were no longer passing, the operation shifted to car storage and a staging point for the coal trains crossing the river to the power plant at Relief, OH. Local traffic destined for industries in Belpre also originated here. Initially, the former mainline remained intact east to Walker to service Westvaco Lumber. Once operations ceased there, the former mainline track was subsequently removed from Walker to just east of the Parkersburg city limit at Stewart. In reality, the sever point is now located at the east end of the High Yard.

B&O Class B-54 4-6-0 #256 at the Parkersburg roundhouse circa 1920. The Ten-Wheelers were the passenger power early in the century until displaced by the 4-6-2 Pacific. The 4-6-0s did survive in secondary service into the twilight years of steam. Image courtesy Ken Adams/North Bend Rail Trail Foundation.

|

Left: On August 20, 1989 the Parkersburg roundhouse was destroyed by fire--a most ignominious end to a historic structure---determined as an act of arson. As this and the image below attest, the damage was devastating. The "safety first" slogan and sign stand out in stark irony. Image courtesy of Todd M. Atkinson.

Another view of the destruction. Not much remained except for the steel structural skeleton and the brick walls. Image courtesy of Todd M. Atkinson

|

In 1989, the Parkersburg roundhouse burned to the ground, a target of arson. In addition, the turntable was removed preventing the turning of locomotives to lead in which direction was necessary. The loss of the roundhouse and turntable was a symbolic ending of the B&O/Chessie transition to CSXT coinciding with the loss of the mainline. Locomotive turning has since been done on the wye across the river in Belpre as needed.

Parkersburg as it was a half century ago. GP30 #6973 leads a paused Cincinnati 97 at OB Tower in the High Yard on a glorious summer day in 1964. The wood C6 class cabooses further sweeten this image. Both B&O and its mainline have long since perished but scenes such as this preserve the memories for posterity. Image courtesy Dave Dupler/Art Markley collection.

|

OB Tower at the High Yard in 1968. This was the central control point of operations in the yard. It was also the crew change point for Monongah and Ohio Division crews. At one time this structure had a second story. Dan Robie/ John G. King collection

A scene planted firmly in the Chessie System era. A yard job goes about switching as a westbound manifest (Cincinnati 97 or Gateway 97) is prepared for the resumed trip west. Image courtesy Dave Dupler

|

A dreary 1982 winter view looking east through a bare High Yard and at OB Tower. Note the track reduction in this scene as compared to the 1964 image above. Image courtesy Dave Dupler/Art Markley collection

View looking through the mist of the day---and time---at a westbound manifest picking up or setting off a block of cars. This is probably Cincinnati 97 as GP40 #4063 idles on an adjacent track. Image Karl Underwood/Todd M. Atkinson collection

|

Parkersburg once flourished with heavy industry which generated carloads of traffic for B&O. Although most industry was related to oil and gas, a substantial amount of various manufacturing existed in the region as well. Chemicals at DuPont plant in Washington and the Shell refinery in Belpre, OH increased rail traffic proportionately as did the American Viscose Corporation. A listing of the shippers served by the B&O from the main line and High Yard during the 1940s is extensive: US Quarry Tile Company, Corning Glass Company, Vitro Agate Company, Standard Oil Company, Pure Oil Company, Cut Rate Lumber Company, Union Live Sales Stock Company, Kieckhafer Container Corporation, WV State Road Commission, Parkersburg Rig and Reel Company Plants #3, #4, and #6, Acme Fishing Tool Company, Parkersburg Grocery Company, Northrup Equipment Company, Monongahela Power Company, Parkersburg Mill Company, Citizens Coal Company, Citizens Lumber Company, Ohio River Sand and Gravel Company, Southern States Corporation, Peerless Milling Company, Parkersburg Distributing Company, Parkersburg Storage and Transfer Company, Ideal Corrugated Box Plants #1 and #2, Plate Construction Company, Parkersburg Tri-Pure Water Company, Central Distributing Company, Graham Packing Company, Berdine Brothers, Spur Distributing Company, Parkersburg Rig and Reel Company #2, Grossman Shoe Company, Citizens Transfer and Storage, Universal Supply Company, and the Berry Hatchery.

|

SY Tower, the guardian of the east end of the Parkersburg High Yard at an unknown date. When this tower was closed, all yard control was shifted to OB Tower at the west end of the yard. Dan Robie/John G. King collection

A forlorn 2002 view of what remains of the Parkersburg Branch east of the High Yard. The former mainline is but a stub for car storage extending past the location of where SY Tower once stood. Image courtesy of Adam Burns

|

Perhaps the most noted of the Chessie System locomotives, the gold GP40-2 GM50. Here it leads Gateway 97 west near the former location of SY Tower in 1979. Image courtesy Dave Dupler/Art Markley collection

B&O fans and historians of the Parkersburg Branch/St.Louis mainline owe a debt of gratitude to the memory of the late Art Markley. Images of this line are scarce compared to other B&O regions and we are grateful Mr. Markley spent time trackside here. Special acknowledgement is also due Dave Dupler for making Art's work visible for all to see. |

B&O GP40-2 GM50 again passes through Parkersburg on a run over the St. Louis main this time on the point of a St .Louis Trailer Train. It is crossing over Worthington Creek preparing to enter the High Yard. Image Karl Underwood/Todd M. Atkinson collection

Not unlike other industrial centers, the Parkersburg region declined in the latter 1900s as heavy manufacturing closed, downsized, or was lost to imports. The area today is still busy but certainly not with the number shippers as in past years.

Along the Little Kanawha

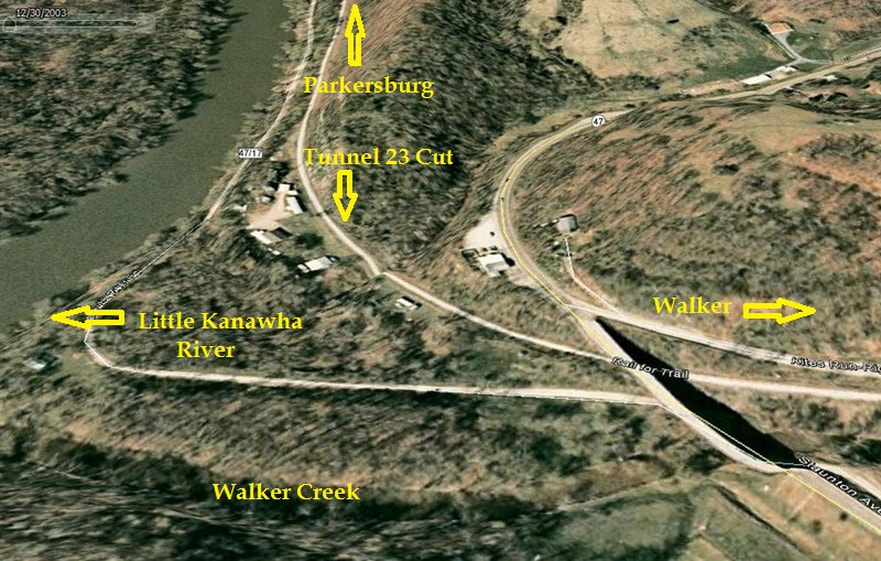

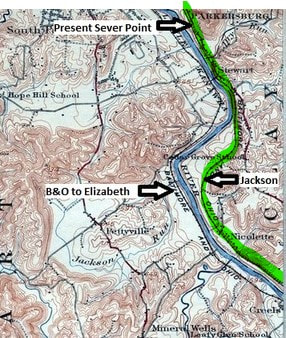

Moving east from the limits of Parkersburg, the B&O main line (green) paralleled the Little Kanawha River and State Route 47 for roughly eight miles. Along the way, it passed through small communities such as Stewart, Jackson, and Nicolette. Of note is Jackson where the first passing siding east of Parkersburg was located.

B&O also occupied the opposite bank of the Little Kanawha as well until the route was abandoned in 1937. This is the branch line that followed the river to Elizabeth as seen on this sector of a 1904 topo map.

B&O also occupied the opposite bank of the Little Kanawha as well until the route was abandoned in 1937. This is the branch line that followed the river to Elizabeth as seen on this sector of a 1904 topo map.

East of Parkersburg, the B&O mainline followed the comparatively level terrain of the Little Kanawha River in contrast to the small gradients it would encounter to the east. Once clear of the of the east end of the Parkersburg High Yard and SY Tower, single track main crossed Worthington Creek and remained so until reaching the first passing siding at Jackson (JA Tower). In the pre CTC days, an operator was stationed there.

|

The Philadelphia Trailer Train races eastbound near Stewart circa 1983. B&O GP40-2 #4427 is on the lead as this class of locomotive was common on this and most Chessie System trains. The Parkersburg Branch as a through route had only a couple of years left by this date. Jerry Doyle photo

|

Cumberland 94 runs east near Nicolette with a combination of F7A and B units on the lead. The year is 1974 and these noble but tired locomotives are on their last revenue run before being traded in to EMD for new power. Dan Robie/John G.King collection

|

|

A story here with the eastbound Wilmington Trailer Train lost to time. The lead locomotive on this train must have failed leaving GP30 #6957 in the lead long hood forward. Perhaps no unit was available at Parkersburg to add on so this train ran at least to Grafton like this. Image Karl Underwood/Todd M. Atkinson collection

|

This 1992 image looks westbound at the abandoned mainline between Stewart and Nicolette. It was not long after this photo was taken that CSX removed the remaining segment between Parkersburg and Walker. Requiem for the route of the National Limited. Dan Robie 1992

|

There was very little in the way of industry along this stretch of track. Once east of Parkersburg, the Branch became essentially single track mainline with on line shippers sporadically spaced. One exception was at Stewart with the US Quarry Tile Company located beyond the east Parkersburg yard lead at SY Tower.

The railroad in this region east of Parkersburg was readily accessible and a number of photos have appeared from this area. If the line were still active today, it would no doubt be popular with untold numbers of digital images taken. Today, however, only roadbed remains and the western terminus of the North Bend Rail Trail is located in the vicinity of Happy Valley.

The railroad in this region east of Parkersburg was readily accessible and a number of photos have appeared from this area. If the line were still active today, it would no doubt be popular with untold numbers of digital images taken. Today, however, only roadbed remains and the western terminus of the North Bend Rail Trail is located in the vicinity of Happy Valley.

An eastbound Philadelphia Trailer Train holds the siding at Jackson in this circa 1980 photo. It must have been another priority train en route such as Gateway 97 or the St. Louis Trailer Train for this train to take the siding. Image Karl Underwood/ Todd M. Atkinson collection

|

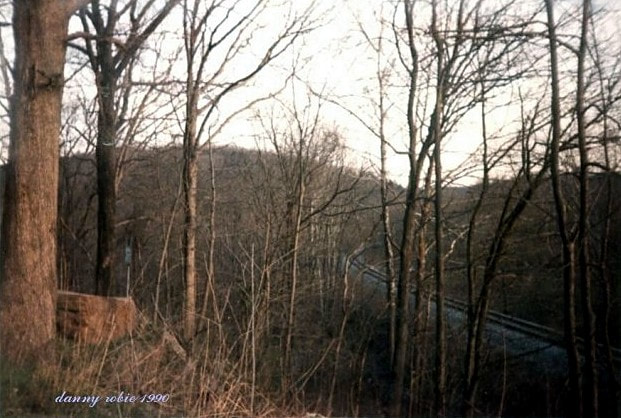

Eastbound view of the former mainline and the recent removal of the north passing track siding at Jackson. This area lies between Stewart and Nicolette. Dan Robie 1990

|

West view from the west end of the former siding at Jackson. The CPL has been turned away from the track since mainline has been severed, A little shine on the rails from trains still running to Westvaco at Walker. Dan Robie 1990

|

Western Maryland power added its own touch of class and color during the Chessie System era with GP35 #3576 leading B&O GP40-2 #4333 near Nicolette. The year is circa 1979 and the train is Cumberland 94 running east on the Parkersburg Branch towards Grafton. Image courtesy Dave Dupler/Art Markley collection

Davisville Towards Walker

The Parkersburg Branch (green) continues to follow the cozy confines of the Little Kanawha River from Davisville to just past Kanawha (Station). At the mouth of Walker Creek, the railroad turns east and follows the stream to the town bearing the same name. With the flat river valley now behind, the line begins the trek through its toughest stretch between Parkersburg and Clarksburg.

|

Two views taken of the abandoned right of way at Davisville looking west and east, respectively. When these 2002 photos were taken, the track here had only been removed within the decade. The gutted CPL which once governed movements for uncounted trains stands as a solemn relic but still identifying the location as Milepost 376.5. Both photos courtesy of Adam Burns

|