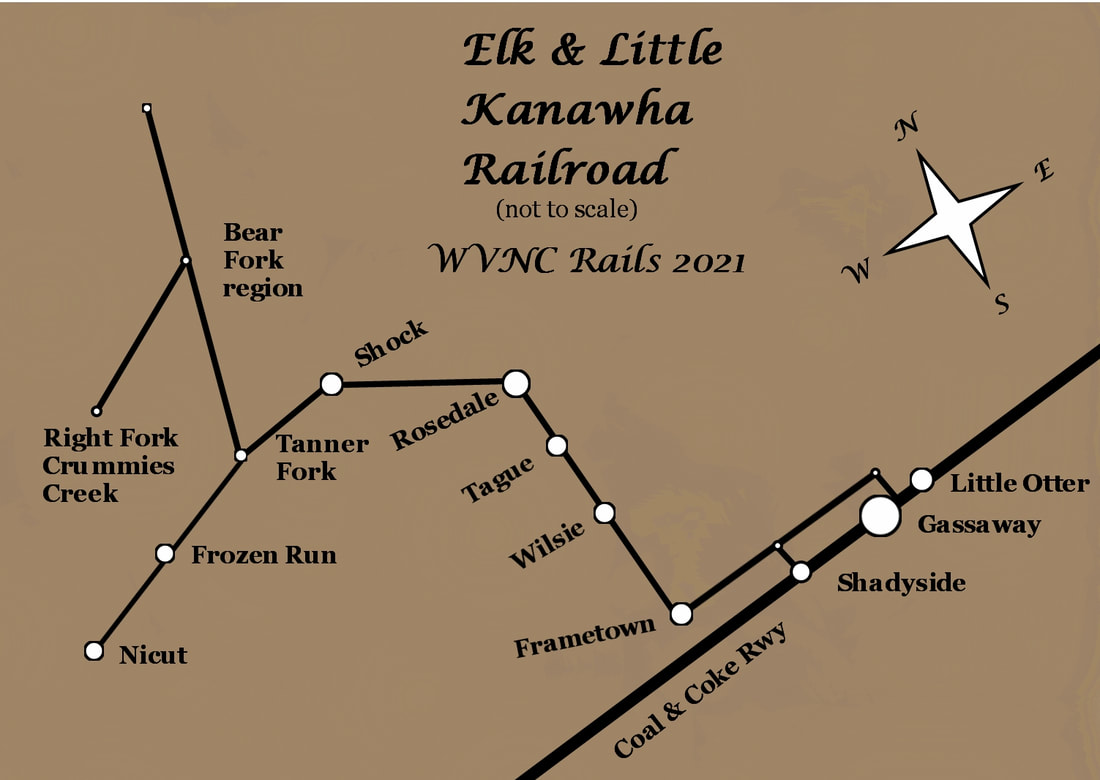

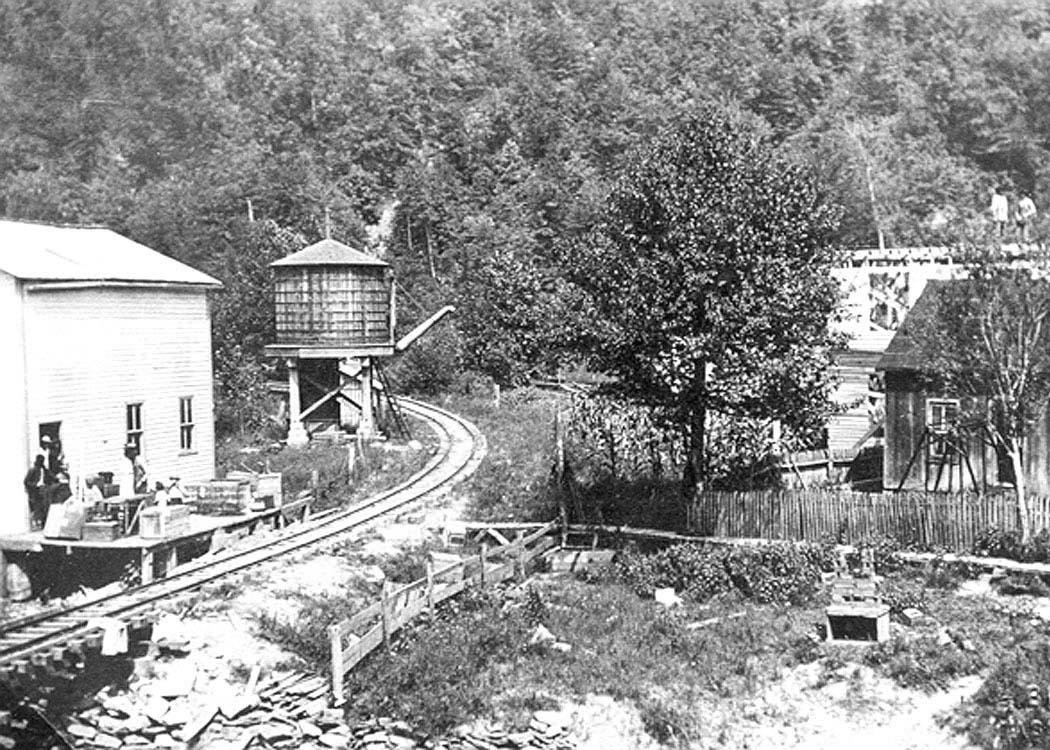

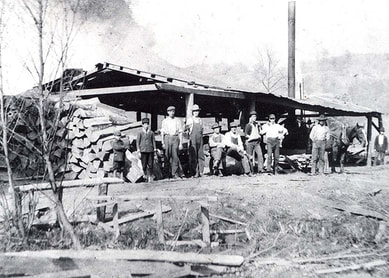

The lumber mill at Bear Fork was located deep in the forests of Gilmer County along the outer reaches of the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad. For nearly a decade, the region served by the E&LK Railroad boomed with the abundance of natural resources. Image Ron Miller collection

Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad

If history were a baseball pitcher its repertoire would consist primarily of curve balls and change ups. There would be the occasional fast ball mixed in for good measure mesmerizing one with a stunning fact creating a sense of awe. But more often than not, history is a master of deception as the researcher hunting for long lost clues can be misled in the quest of separating fact from fiction. Striving for accuracy is challenging but ultimately rewarding for each secret that is uncovered is one less lost forever to time. Recorded history is also an accumulation of building blocks added in stages by means of subsequent research and newer technologies uncovering previously unknown details. Hence, the search for the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad is, in effect, an example of the aforementioned analogies.

|

The Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad is on the list of long lost West Virginia railroads that operated during the early 20th century. Most of them served a specific purpose until vanishing into obscurity with scant documented history of their existence. The overwhelming number of smaller railroads in the Mountain State were built into the backwoods to extract the massive virgin timber stands predominately located in the central and eastern regions. Seldom did any of these roads rely upon supplemental or secondary means of revenue although the E&LK was an exception. Once the timber was cut and the forests exhausted, their means for existence ceased. The rails were taken up and either scrapped or reused elsewhere--- all that remained was roadbed and memories.

|

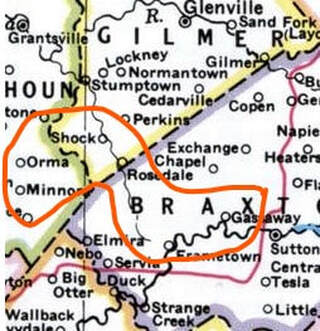

Regional map of central West Virginia with multiple counties. The area that the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad operated is within circled area.

|

Fortunately, in the case of the Elk and Little Kanawha Railroad, there were individuals with the wherewithal to preserve a significant amount of its history with the written word. Although the memories were not exclusively those of the E&LK, they nevertheless encompassed a considerable amount of recollection due to the commercial significance. Historians in later years explored the territory tracing the railroad right of way and certainly no less important, conversed with area residents who had either first hand knowledge or historical insight. It was fortuitous that these actions were undertaken when they were---today it would be impossible as there are no surviving residents with any memory of the E&LK. Inasmuch, there are details that are not exact--build and expansion dates, for example, that differ depending on the source. What is certain, however, is that the E&LK existed in the time span of 1909 to 1918.

We can thank the undertaking of three primary individuals for the research of the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad. Bob Weaver--historian and webmaster for the Hur Herald web page dedicated to north central West Virginia--- and the the late Harlan Stump and Ron Miller, respectively, for archival images and historical research. These efforts began during the 1980s and continued until circa 2001. Certainly, there are other individuals ---notably Annie Harvey Dulaney-- on a singular accord whose detailed written account from the era assisted the three gentlemen in their research. The fruits of their work appeared in separate articles published on the Hur Herald in 2000-2001. My eager task with the support of Bob Weaver is to preserve their efforts on WVNC Rails with a consolidation of their research and material formatted to this site in 2021. Any additional information and images subsequently uncovered about the railroad will be inserted into this works.------Dan Robie

Condensed History

West Virginia was an orchard of promise ripe for harvest during the first decade of the 20th century and its optimism shone throughout the Elk River valley. The region was rich with natural resources and the railroad was coming as a harbinger to prosperity. To the west in neighboring Clay County, the Charleston, Clendenin & Sutton Railroad was completed beyond Clay Court House (Clay) to Otter (Ivydale) by the turn of the century. Greater ambitions were in the works, however, when Henry Gassaway Davis purchased the railroad with the intent of expansion to Elkins. Chartered as the Coal and Coke Railway in 1903, it was at the vanguard of industrial development in Braxton County along the Elk River. Geographically, Braxton County--namely the location that became Gassaway--was established as the mid-point on the Coal and Coke Railway resulting in the construction of a large yard and locomotive service facilities. At the end of the decade, another railroad would appear at Gassaway built to tap the natural resources in the tri-county region of Braxton, Gilmer, and Calhoun.

A circa 1915 view of the Coal & Coke Railway shops at Gassaway. This perspective looks directly across the Elk River to the opposite bank on the north side. A close inspection will reveal a rare glimpse of the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad right of way during its brief existence. Image West Virginia and Regional History

The early history of Braxton County suggests that discussion of a line that would become the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad predated the construction of the Coal and Coke Railway along the Elk River into Gassaway and beyond. The proposal was for it to interchange with the B&O Railroad to the east although it was a challenging task. Discussion of the railroad was shelved for several years. Once the Coal and Coke Railway was completed through the area by 1906 talk was revived in a more plausible vein.

|

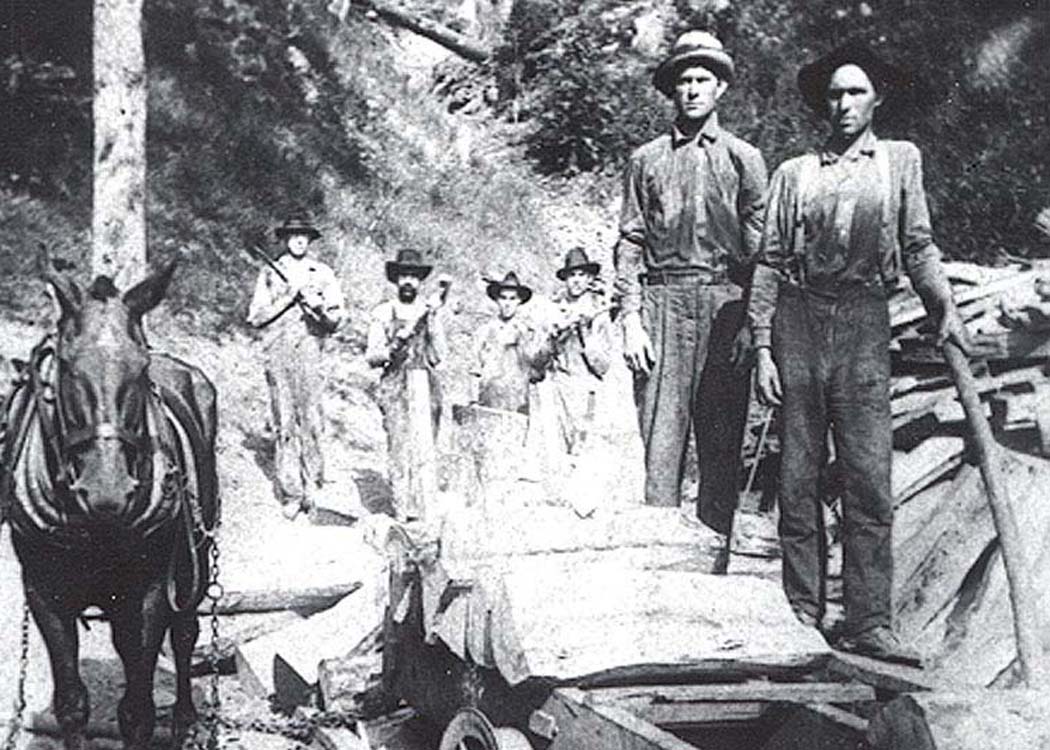

Building railroads before mechanization was tough work. These men were among the group of workers that had the arduous task of constructing the E&LK Railroad. Image Ron Miller collection

|

The catalyst for the creation of the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad was in September 1909 when the Standard Oil Company opted to construct a narrow gauge railroad through a massive timber tract. Interstate Cooperage Company, a division of the Standard Oil Company, had been operating on a 28,000 acre tract located between Gassaway and Rosedale of which a railroad would benefit. In 1910, construction of the railroad began on the north bank of the Elk River at Gassaway and continued to Frametown. From this point, the line turned north along Big Run Creek paralleling the stream until crossing the divide to the Steer Creek drainage and, ultimately, to Rosedale. Further expansion by 1913 saw the road reach Shock and from there, extension into the heavily forested Bear Fork region of Gilmer and Calhoun Counties.

|

|

That the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad was built solely for serving the timber country and saw mills but as a common carrier was later required to diversify . The trains hauled out the product of the mills---wooden staves for oil barrels---for the booming oil business both along its rails and elsewhere in the state. Millions of staves were cut and stockpiled for transport to the Coal and Coke Railway for furtherance to multiple destinations. During the short life span of the railroad, it also hauled passengers to and from the Elk Valley in addition to general freight for locations such as Rosedale and Shock. Although rail transport was the pre-eminent means other sources were utilized. Oxen teams hauled wagon loads of staves to and from the E&LK and cut timber was floated downstream from Bear Fork on the Little Kanawha River to Parkersburg.

|

Oxen factored prominently in early West Virginia industry. Not only were they used in coal mines but also in the timber business as is pictured here along the E&LK. Image Ron Miller collection

|

|

A tramcar with men and logs moves through the Bear Fork area. Horses and oxen were the common means of power to pull the cars in these remote stretches. Image Ron Miller collection

|

During the years 1913-1917, the E&LK fulfilled its mission of hauling the commodities from Braxton, Gilmer, and Calhoun Counties. But by the time of American entry into World War I, the timber stands in Braxton County and the Bear Fork region were readily exhausted. The oil boom at Rosedale had also subsided leaving the railroad with little remaining revenue. Although its primary means of existence had disappeared it is regrettable that the lingering loss was passenger service from Gassaway to the remote regions. At this date, roads were mediocre at best and it would not be until the following decade that improvements began. In 1918, the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad ceased operation and the track was subsequently removed. Later highway expansions and improvements would utilize the former E&LK right of way at various locations.

|

History recorded that flooding in 1916 severely affected the right of way along the E&LK. Track was washed away and bridges were heavily damaged or destroyed altogether. Typically, on a railroad as small (approximately 40 miles of track) as the E&LK this catastrophe would have signaled its death knell. But the fact that the line was rebuilt and operated for yet another two years is testament that sufficient resources remained to offset the losses.

It is interesting to note that the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad optimistically explored constructing its line to Parkersburg early in its existence. Another proposed development that did not materialize was a rail connection for the E&LK in Gilmer County along the Little Kanawha River. From Parkersburg, the Little Kanawha Railroad was constructed with the intention of reaching Burnsville but was completed no further than Owensport in Wirt County. There were grand visions for this ill-fated (Little Kanawha Syndicate) railroad for incorporation into a competing trunk line but maligned financial and legal issues rendered the prophecy unfulfilled. Had this railroad been completed through Calhoun County the tentative plans called for the E&LK to connect with it at Russett but obviously these plans never came to fruition. Although the Little Kanawha Railroad and a subsequent connection to it by the E&LK were not realized it makes for curious conjecture that had this occurred would the life span of the E&LK have been extended. Whereas the answer to the heretofore mentioned will never be known one fact is for certain--the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad holds the distinction as the only railroad to exist in Calhoun County.

Gassaway to Frametown

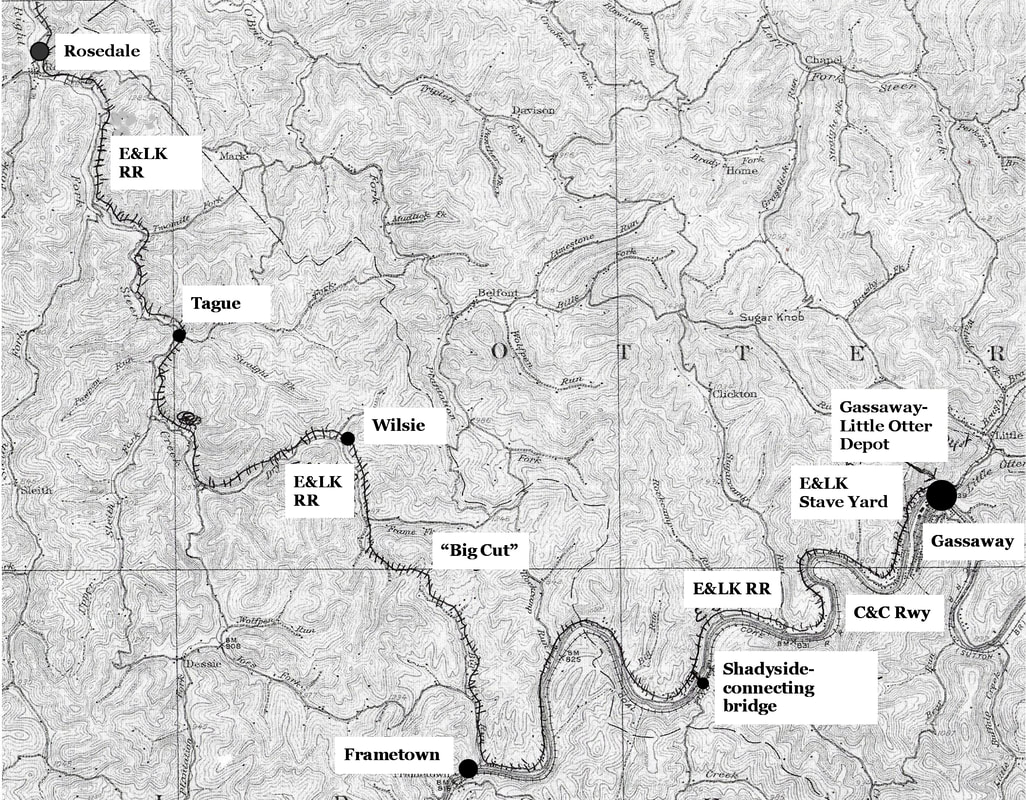

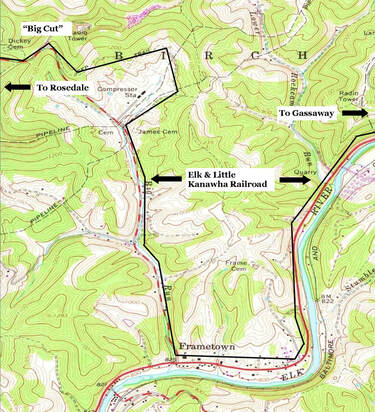

A 1912 topo map populated with the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad and its significant locations in the Elk River parameter. The railroad was aptly named as it traversed the watershed of both rivers for which it was named. This map highlights the Braxton County section from Gassaway to Rosedale.

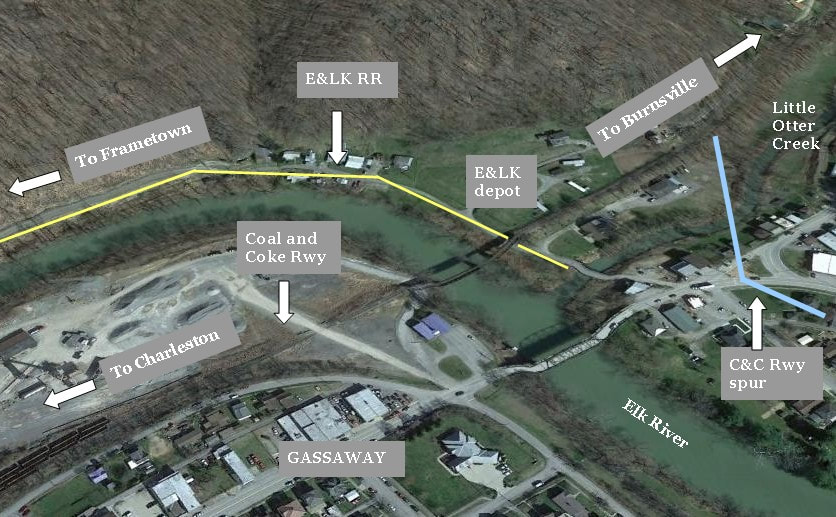

The Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad interconnected with the outside world at Gassaway. Located at the mouth of Little Otter Creek, the railroad constructed a depot used for passenger and freight service in addition to a turntable on which to spin its locomotives. These facilities were located on the north bank of the Elk River in proximity to the river crossing by the Coal and Coke Railway. In the period photo above, the Coal and Coke Railway connection to the E&LK is visible as the trestle that spans Little Otter Creek.

A remarkable image at the north side of Gassaway circa 1915 that yearns for more detail. This view looks northeast across the Elk River and the mouth of Little Otter Creek. At left is the Coal and Coke Railway---soon to be B&O---spanning the river. The trestle at right is the C&C connection to the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad and in the center, what appears to be an engine house. In the foreground is the 1895 Davis Memorial Presbyterian Church which still stands today. Image West Virginia Economic and Geological Surveys

|

Though not exact, this is the approximate configuration of the E&LK RR at Gassaway highlighted on a contemporary image. What is uncertain at present was the the exact relationship of the C&C spur to the E&LK. It was here that wooden staves were transloaded from the narrow gauge (E&LK) yard to standard gauge (C&C) railroad.

|

Of prime importance along the river at Gassaway was generous bottom land that contrasted with the typical tight confines of the valley elsewhere. The E&LK chose the location to stockpile the wooden staves cut from timber in the saw mills at Bear Fork. Trains loaded with staves arrived at Gassaway for transload to the Coal and Coke Railway. Because of the difference in track gauge (Coal and Coke-standard and E&LK-narrow), interchange of rail cars was not possible. Thus, staves were unloaded from E&LK railcars and trans-loaded on those of the Coal and Coke for shipment to various oil fields for the manufacturing of oil barrels. The E&LK depot also served the patrons that traveled between Gassaway and Bear Fork and/or transferring between trains of the Coal and Coke Railway. Whether the passengers could flag a C&C train on the north bank of the Elk or had to shuttle to its Gassaway station is not documented in the exact sense.

|

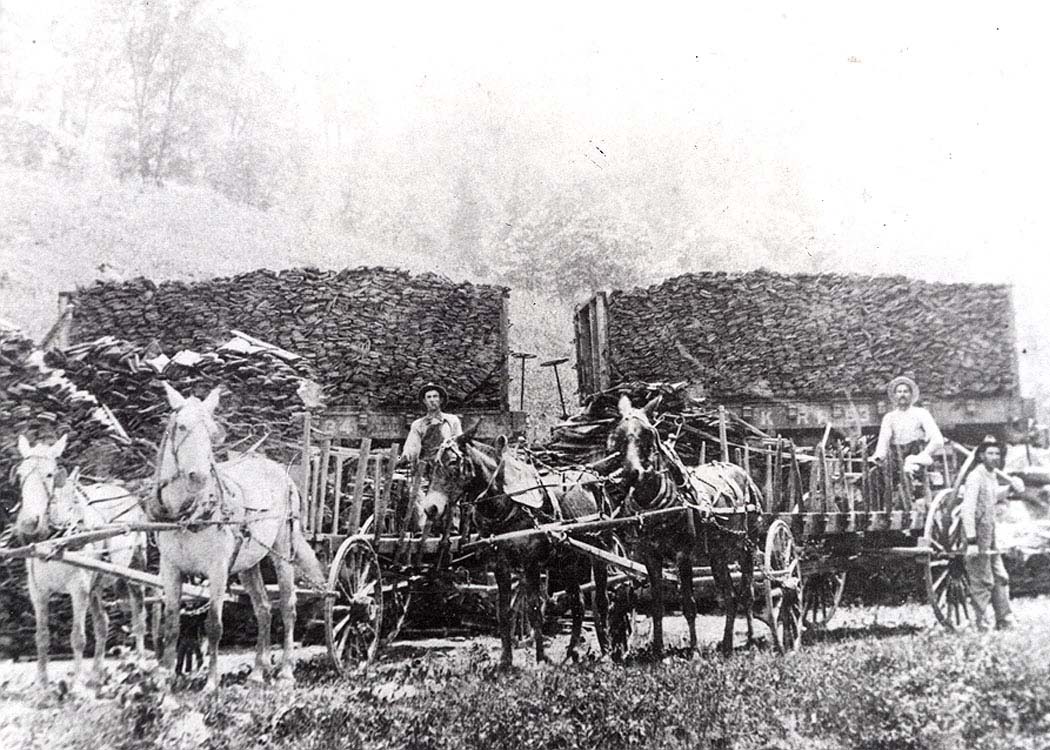

Thousands of barrel staves from the Bear Fork region destined for Gassaway. The E&LK generated a tidy business for the Coal and Coke Railway during its decade of existence. Image Ron Miller collection

A century later, it is unfortunate that little remains of the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad existence. Perhaps saddest of all is the loss of the Gassaway depot and turntable that occupied the north bank of the Elk River. As fate would dictate and in line with the demise of the railroad, floodwaters from the Elk River washed away both structures in 1918.

Moving west from Gassaway, the E&LK paralleled the Elk River for nearly nines miles until reaching Frametown. There is little evidence today that a railroad existed here---after the track was taken up in 1918, roads utilized the former right of way. These thoroughfares, however, serve as a guide to where the track once lay on the north bank of the river. South State Street is on the north bank opposite the town of Gassaway and where it intersects with WV Route 4 is the location the E&LK also turned. During its existence, the track actually shared the right of way with the highway creating a potentially dangerous co-occupancy of train, vehicle, and wagons.

|

Approximately halfway between Gassaway and Frametown was a spur from the E&LK that crossed the Elk River at Wire Bridge (Shadyside). This spur was built and owned by the Boggs Stave and Lumber Company which operated dedicated trains between its mills at Bear Fork and Shadyside. The Boggs Stave and Lumber Company operated a store while transloading its staves to the Coal and Coke Railway for shipment bypassing the large stave yard at Gassaway. Perhaps the company also utilized the yard at Gassaway--- it is possible that the staves unloaded at Shadyside were transported west to the Blue Creek oil field in Kanawha County or beyond to Charleston itself. There is no mention from previous research if any remnants from either the Boggs Stave and Lumber Company or the bridge crossing (piers) at Shadyside still exist. As it was a "wire bridge", all traces may have vanished when the railroad ceased.

|

Ox teams were a source of pride for those engaged in the timber industry. They were the family vehicle for both work and domestic needs in the era predating trucks and good roads. Image Ron Miller collection

Two images of the Boggs property taken near Shadyside. The family was prominent in the construction of wood staves operating in three counties (Braxton, Calhoun, Gilmer) during the early 1900s. Boggs Stave and Lumber Company at Shadyside was a major player in the brief history of the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad. Images courtesy of Alex Brady

|

It was at Frametown where the Elk & Little Kanawha River Railroad ended its parallel with the Elk River and turned north at the mouth of Big Run. The town itself was of little commercial importance along the E&LK although it was a passenger stop. A primary reason for the relative insignificance is the town location west of Big Run which essentially resulted in the railroad bypassing it. There is record of a siding located here used for general merchandise but no freight or passenger depot. During the era of the E&LK, Frametown claimed a population of 150 and was served by various businesses. Included in the group was a millinery shop, blacksmith shop, grist mill , barber shop, coffin shop, and a livery stable. Rounding out the community occupants were a hardware store, jail, school house, and a Methodist church.

Big Run to Steer Creek-Crossing the Divide

|

A 1965 topo map of the Frametown area provides clarity. The general route of the E&LK as it once existed along the Elk River and Big Run to "Big Run Cut". Note right of way at gas compressor location.

|

West of Frametown, the railroad adapted the archetypal setting of a mountain railroad by paralleling the narrow but crooked Big Run on a gradual ascent. From Frametown with an elevation of 840 feet above sea level, the line increased to over 950 feet elevation near the headwaters of Big Run in proximity of Wilsie. This particular grade did not pose a detriment to the E&LK as the tonnage drifted downgrade here. At the summit a tunnel was proposed to span the divide but instead, a cut was blasted out which became known as "Big Run Cut". This point separates the watersheds of the Elk and Little Kanawha Rivers, respectively. Although Braxton County Route 9 (Wilsie Road) is paved over the right of way sharp eyed observers can spot century old telltales of the E&LK existence along Big Run. Most notably is at the Columbia Gas compressor station east of Wilsie---the right of way swings around the hill here on the approach to "Big Run Cut" then descends at the headwaters of Dry Fork.

|

The region from "Big Run Cut" that paralleled Dry Fork beyond Frame Fork to Rosedale was also on a gradient. This one, in contrast to the Big Run Grade, faced loaded trains bound for Gassaway. The elevation at Rosedale is 778 feet but the westbound climb reached 950 feet near "Big Run Cut". Fortunately, the geared Shay and Climax locomotives which traversed the E&LK were in their domain performing the work they were built to do--pulling trains on steep mountain grades.

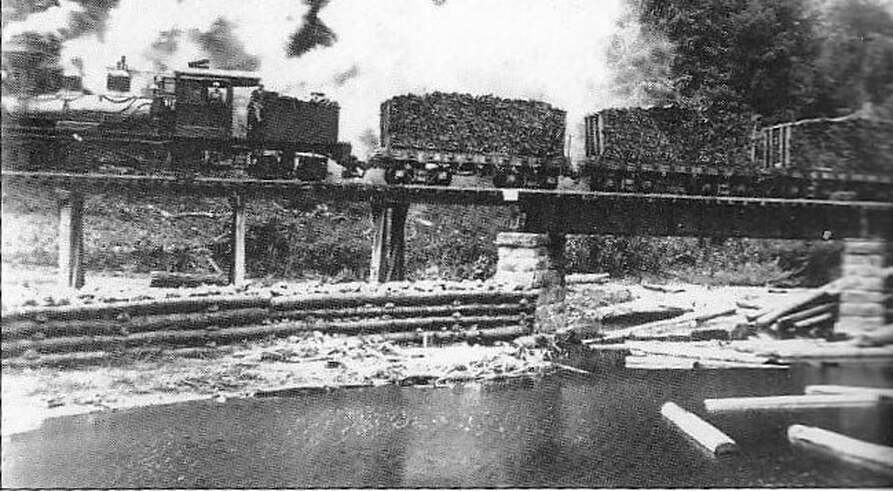

One of the few images of an Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad train on the line. We are grateful to the photographer nameless in time that captured this image of a stave train crossing the creek at Tague bound for Gassaway. Also of note are the logs floated downstream on Right Fork Steer Creek. Image courtesy Smithsonian Institute.

An examination of the few line of road images indicate differences in track condition. The "main" line from Gassaway to Shock was ballasted but the stark difference was in bridge construction as seen in the photo taken above at Tague. Stone piers with steel decking was at least partially used on the main to Shock. Beyond that point extending into the Bear Fork region, timber was used exclusively for bridges. Photos on this page reveal solid timber decking and pier construction which sufficed---it was cheaper, readily available, and quicker to build. There may be no remaining evidence as to whether these structures were left to stand in Bear Fork after the railroad was abandoned in 1918.

During the first three years of operation on the E&LK (1910-1913), the region from Frametown to Rosedale teemed with activity. Timber camps developed in the creek basins and wherever they emerged, the workers-- mostly Italian and Swedish immigrants along with locals--followed accordingly. Temporary spurs were constructed and in conjunction with horse or ox pulled carts, the timber stands were harvested. Once the railroad expanded into the Bear Fork region, that area became the dominant source of timber and cut staves. One notable camp existed at Grose situated between Big Run Cut and Tague. Located here were saw mills, a general store, houses, and an area for stave stacking. Trains destined for Gassaway stopped and were loaded with the staves stockpiled from the neighboring mills.

Rosedale and Shock

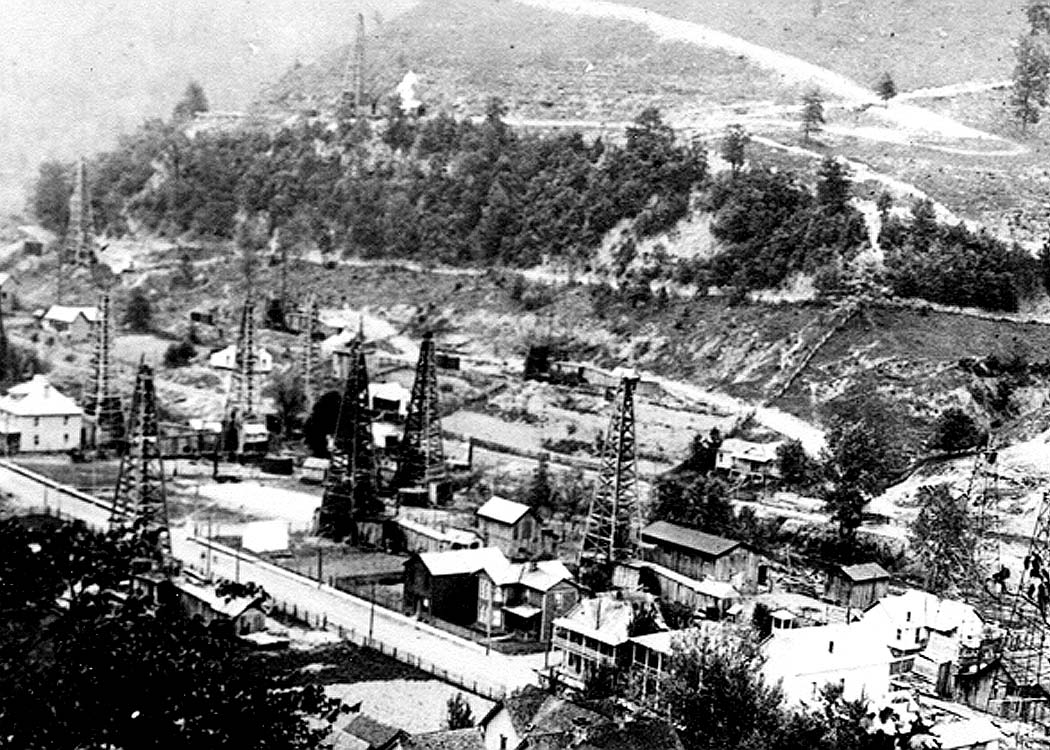

During the late 19th-early 20th centuries, West Virginia hosted any number of boom towns that sprang up overnight as quickly as mushroom. Usually, it was the discovery of one commodity---either coal or oil--that created a rush for wealth and the zeal to build a supporting town to pursue those riches. The town of Rosedale straddling the Braxton-Gilmer county line can lay claim to not one but two simultaneous resources---oil and timber-- which made the community an embarrassment of riches for almost a decade.

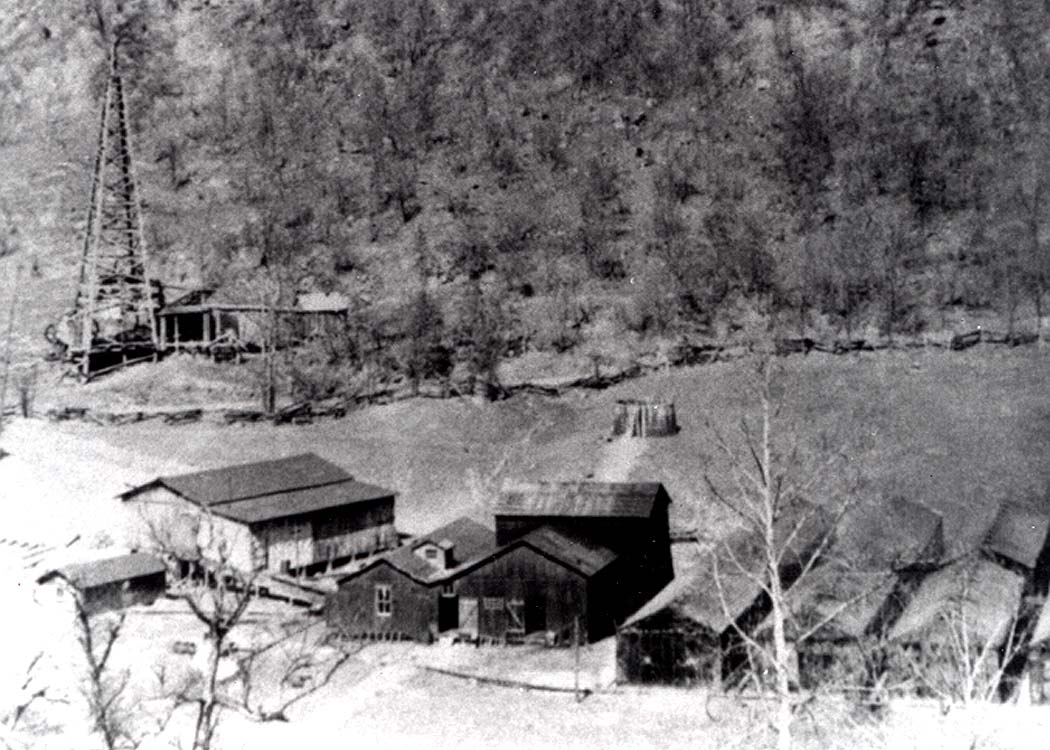

Excellent right of way scene along the E&LK circa 1913. Location is not identified but could possibly be south end of Rosedale at Right Fork Steer Creek with the store and water tank. Image Ron Miller collection

|

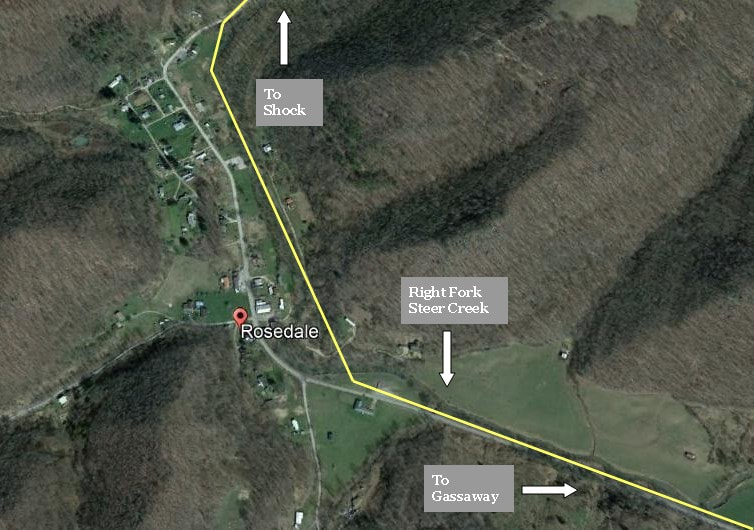

Contemporary view of Rosedale and the general path of the E&LK through it. The right of way was on the opposite bank of the creek from the town.

|

Rosedale was an impressive sight during the early 1900s with the oil derricks and the array of two-story houses. It gave an impression with elements of a large city condensed into a smaller one completed by incorporation in 1911. In addition, there was the Peyton Dobbins Flour Mill, blacksmith shop, boarding houses, and two churches---one Baptist and the other Methodist. The railroad passed on the east bank of Right Fork Steer Creek opposite the town center somewhat isolating the depot from Rosedale. Its depot was a combination one handling both general freight and passengers. In her account of Rosedale, Annie Harvey Dulaney noted that the railroad "passed through a vegetable garden" on its route through town.

|

|

Rosedale was a bona fide boom town replete with oil derricks and residential district. Photo taken at its zenith circa 1915. Image Phil Stevens collection

|

Close up of the Rosedale image pictured at left. The number of two-story homes located here at this date bespeaks of the prosperity. Image Ron Miller collection

|

Rosedale survives today but as a small residential community with a couple of businesses. The boom times vanished generations ago but history retains a splendid heritage of the dynamic town it was during the early 20th century.

The oil field at Rosedale is represented by the number of oil derricks. In this period photo circa 1915 the right of way of the E&LK is visible at center on the opposite bank of Right Fork Steer Creek. Image Ron Miller collection

The early 1900s witnessed the emergence of carbon black factories of which several located in the central region of West Virginia. One such operation was constructed along Steer Creek between Rosedale and Shock and was producing during the time of the E&LK. The location was ideal as the primary component--oil--was in abundance at the Rosedale field. As it was located parallel to the railroad, one could presume that it was served by the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad in some capacity. Prior to the 20th century, carbon black was also known as lamp black. It was created by super-heating oil or gas with excessive oxygen in a furnace that left a "soot" residue of which was the carbon black. It uses included ink making, paint pigments, and tire manufacturing for the fledgling automobile industry.

First hand accounts from the era also mention the presence of several lumber mills that existed in the territory between Rosedale and Shock. In an era that predated any significant labor and safety regulations, injuries were frequent both with timber cutting and the saw mills. Rosedale was the closest town for any appreciable first aid treatment serving the timber lands beyond.

The industry scattered along the E&LK was not limited to timber. This carbon black factory was located along the railroad between Rosedale and Shock. Image Ron Miller collection

|

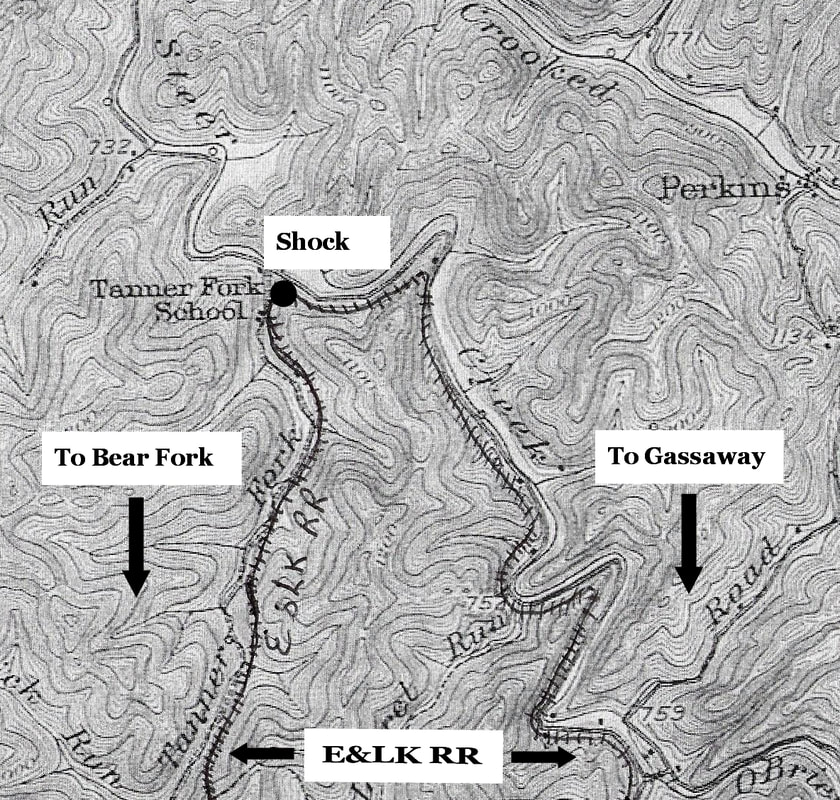

Magnified 1912 topo map of the area surrounding Shock. The E&LK paralleled Right Fork Steer Creek north to Shock then turned south along Tanner Fork which was the gateway to the Bear Fork region.

|

Google Earth view of the sleepy community of Shock as it appears today. The yellow line marks the approximate location of where the railroad once existed. It was here that the line diverged from Right Fork Steer Creek and paralleled Tanner Fork upstream for access to the timber stands of the Bear Fork region of Gilmer and Calhoun Counties. This once active location is now populated only by homes scattered along the creek.

|

In 1911, the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad announced plans for further expansion. By 1912-1913, the railroad was extended along the Right Fork Steer Creek from Rosedale deeper into Gilmer County. The next community of consequence was at Shock located at the confluence of Tanner Fork and Right Fork Steer Creek. Between Rosedale and Shock the railroad was on slight gradient as it paralleled Right Fork Steer Creek but not as pronounced as the territory from Frametown to Rosedale. The elevation at Rosedale decreased from 778 feet above sea level to 741 feet at Shock with loads facing the upgrade.

|

E&LK 0-4-0 #10 and a flatcar are derailed on this bridge probably somewhere near Shock. Cause was probably a bad rail joint. Note the stacked timber piers. Image Ron Miller collection

|

A train load of barrel staves on the line near Shock. These are destined to Gassaway for transloading to the Coal and Coke Railway. Image Ron Miller collection

|

Although the E&LK continued beyond Shock into the Bear Fork region, it was the terminus for what would be considered its actual main line. It was the end of passenger service from Gassaway--any patrons beyond would trek to that point for boarding a train to the Elk Valley. Of course, the opposite was also true with a train arriving at Shock. Workers and residents were not the only travelers along the E&LK, however. Its lore is also populated with the tales of vagrants in search of a handout and peddlers selling wares to make a buck.

|

Oxen were invaluable tugging heavy loads over uneven terrain. This unidentified scene is perhaps in the vicinity of Shock . Image Ron Miller collection

|

This two story house served as the office for the Interstate Cooperage Company. Located at Shock along the E&LK at the mouth of Tanner Creek. Image Ron Miller collection

|

At Shock was situated the third and westernmost depot on the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad. With its location a strategic point along the railroad, both the transfer of passengers and general freight were of importance here. Staves from the Bear Fork mills passed through on the westbound trains returning to Gassaway with empties returned. There is a possibility that a wye existed here to turn locomotives from Bear Fork and also the ones bound for Gassaway. The office for the Interstate Cooperage Company---which oversaw the timber and milling operations--was locally administered from Shock. Also located here was a general store which served the regional community.

Barrel staves were manufactured and hauled to the E&LK for shipping. Horse led teamsters were a common method of transport and the most efficient means of delivery to the rail. Image Ron Miller collection

Bear Fork Country- Gilmer and Calhoun Counties

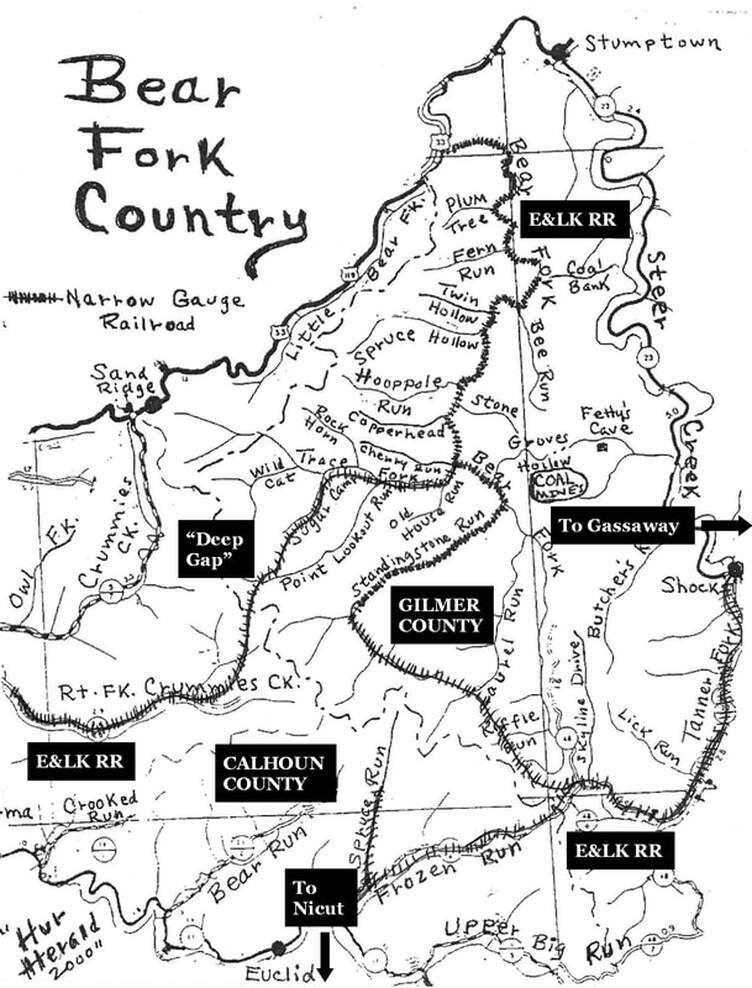

A modified map of the Bear Fork region originally created by the late Harlan Stump and published on the "Hur Herald" in 2000. The original depicted the railroad along Bear Fork but not the later expansions. This map is revised for WVNC Rails with labels and the track extensions to Frozen Run and Right Fork Crummies Creek.

Building a narrow gauge railroad through uncharted territory was painstakingly difficult with numerous obstacles to overcome. As with Class I railroad construction, the presence of a stream to parallel provides a natural contour on which to build. Its size will generally determine how the right of way is constructed---it may possess a plain or there may be bluffs directly adjacent to bank. In either case, the grading of a roadbed will entail the clearing of trees and/or cutting into hillside to create adequate clearance.

The major contrast with constructing a narrow gauge timber route as opposed to a standard gauge is perceived longevity of the line. There was a finite amount of time with the existence of a timber railroad--once the stands were exhausted, the track had fulfilled its purpose. Inasmuch, the construction methods were at times unorthodox with a temporary lifespan as the norm. Track was constructed on uneven roadbed, without ballast, tie spacing largely gapped, and steeper gradients. As long as the route was passable, it generally sufficed.

The E&LK was constructed in this manner. Whereas the "main" line from Gassaway to Shock was ballasted with bridges built with steel on stone piers, the region in Bear Fork was utilitarian. In addition to the above aforementioned track construction methods, bridges were constructed of simple cut timber logs.

Heavy timber is ideal for solid bridge structure. Track would be laid on top of these logs which easily supported train weight. Road construction along Tanner Fork in Gilmer County. Image Ron Miller collection

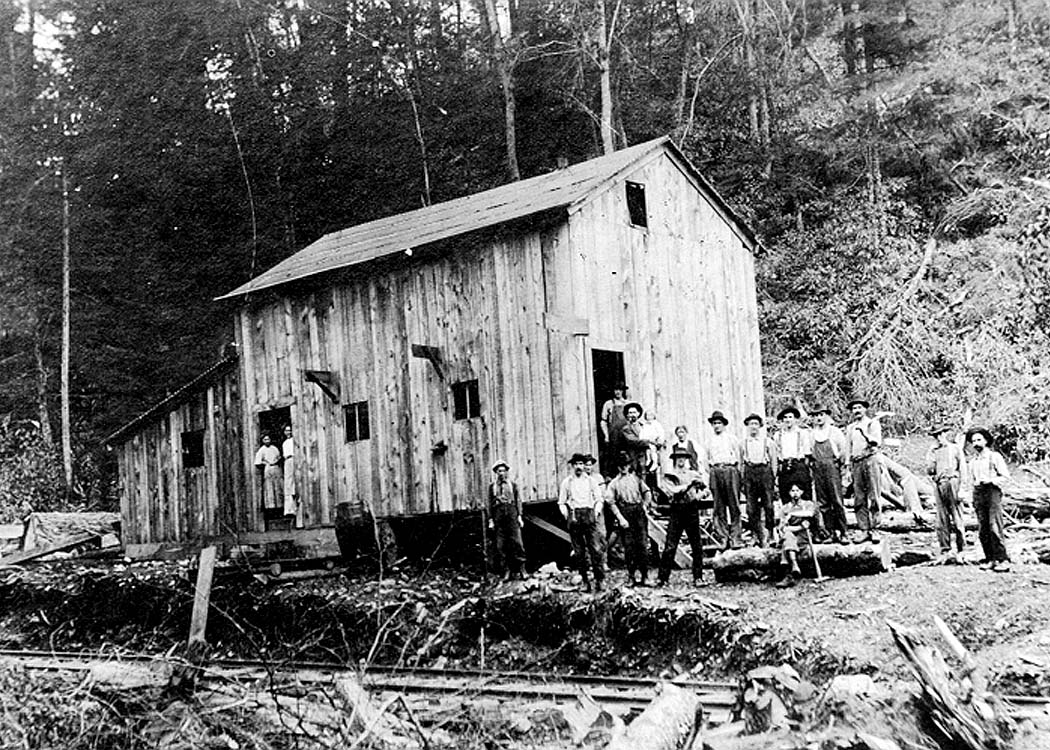

A large group of workers posed for the photographer in this scene along the railroad at Bear Fork in Gilmer County. We are fortunate that a number of photographs were taken in this remote location. Image Ron Miller collection

Gilmer County comprised the greatest amount of timber acreage in the Bear Fork basin. To reach this backwoods region the E&LK "main" line turned north from Frozen Run then crossing the ridge at Laurel Run. From here the line entered the Bear Fork drainage along a tributary called Standingstone Run. Further up the line at Trace Fork--where the north spur to Calhoun diverged-- was the largest saw mill in the Bear Fork territory which produced a great quantity of staves. Beyond this point the railroad continued north passing tributaries with colorful names such as Copperhead Run, Fern Run, and Plum Tree Creek. The line terminated at the confluence of Bear Fork and Little Bear Fork a short distance from the community of Stumptown.

A newspaper account from 1914 reported that a young man was struck and killed by a train operating along Bear Fork. Given the probabilities for such circumstances in this environment, it is fortunate that only one fatality--sad, nonetheless--occurred during the E&LK existence. It is possible there may have been others but if so they are mired in the cobwebs of history.

|

This group of workers posed for an unknown photographer during the expansion into Calhoun County. Laying track in the rugged Bear Fork region. Image Ron Miller collection

|

Railroad was indeed constructed within Calhoun County. Passing through a cut in the Crummies Creek back country. Image Ron Miller collection

|

Horse pulled tram with logs deep in the Calhoun County woodlands. Note the wheel flanges on the outside of the wooden rails built to haul timber from the headwaters of small streams. Image Ron Miller collection

From the main line along Bear Fork near Trace Fork was the "north" spur into Calhoun County. This line paralleled Trace Fork to Sugar Camp passing through an area known as "Deep Cut" The terrain here was especially rugged with numerous switchbacks engaged to travel a distance of three miles. Once attained, the spur continued into the Crummies Creek basin along its Right Fork.

In Calhoun County, the "south" spur of the railroad continued on Frozen Run with a switchback located at Spruce Run. By use of these switchbacks the line was extended further to the Left Fork of the West Fork Little Kanawha River. From this point it reached another five miles to Upper Big Run. Sawmills were scattered but the most important one based on accounts of residents interviewed by Harlan Stump during the 1980s was the Boggs Fork Mill on Frozen Run.

|

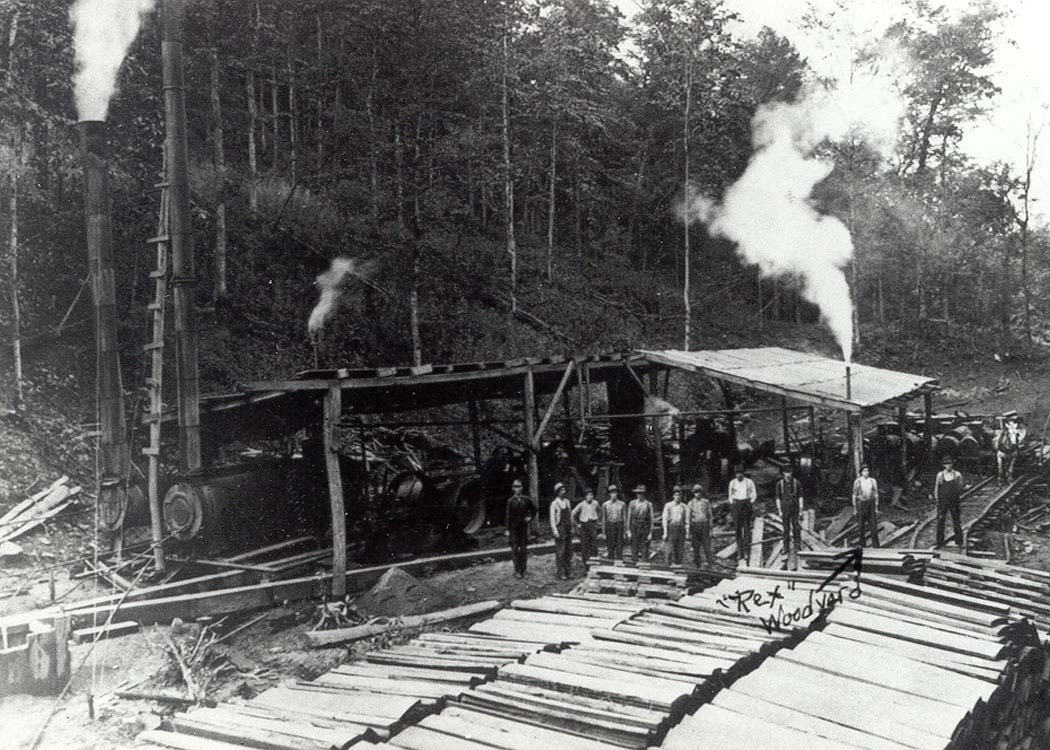

Workers possibly along the E&LK Railroad at the busy Spruce mill off Frozen Run. Note the track and spur for flatcars loaded with staves. Image Ron Miller collection

|

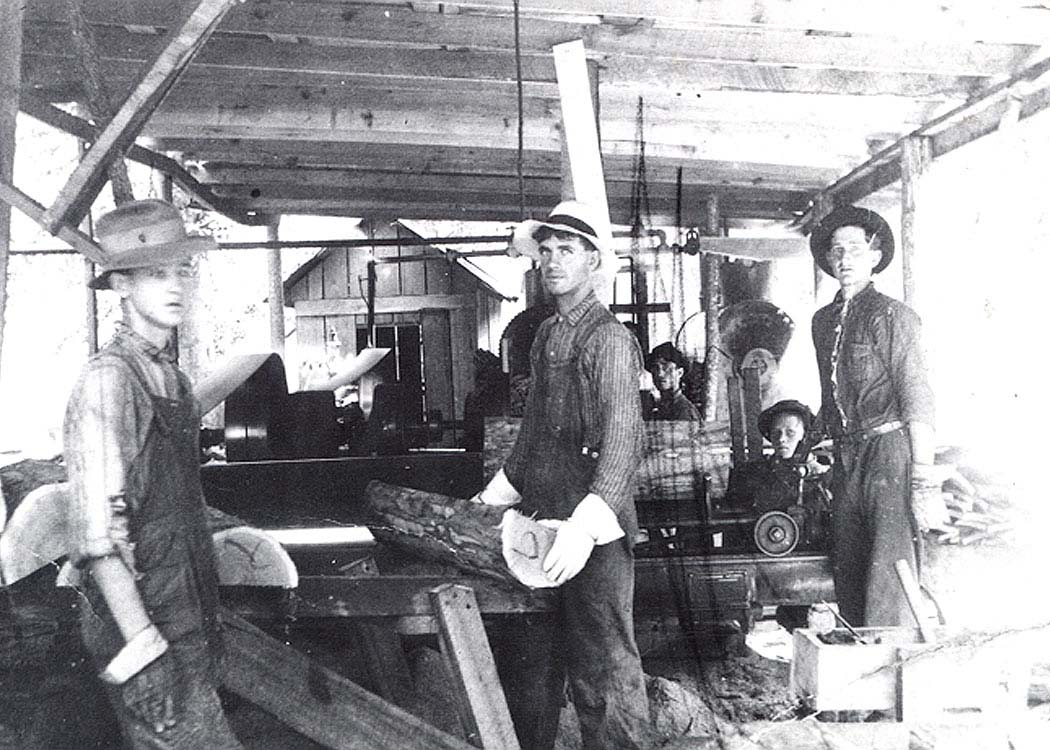

Workers possibly inside the saw mill at Spruce served from Frozen Run. Little did these men know that this moment in time would be viewed a century later. Image Ron Miller collection

|

Contemporary Views-Circa 2000

Below are four photos taken by Bob Weaver in the Calhoun County area of the former E&LK right of way as it appeared in 2000. This was the time period that he and the late Ron Miller were compiling information about the E&LK for publishing on the Hur Herald web page. As these photos were taken two decades prior to this writing (2021) there is more infringement by growth since that time.

|

The "main" line of the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad once passed through here. Clearly defined right of way along Bear Fork in 2000. Image Bob Weaver/Hur Herald

|

An image along the abandoned right of way in the Crummies Creek area in 2000. The railroad had been gone for more than 80 years when this photo was taken. Image Bob Weaver/Hur Herald

|

|

Trains once battled the grades at "Burnt Cabin Gap" in Gilmer County. The route from Sugar Camp to Crummies Creek in Calhoun County as it was in 2000. Image Bob Weaver/Hur Herald

|

It had been 80+ years since the last train passed here when this 2000 photo was taken. Well defined right of way in Calhoun County near Crummies Creek. Image Bob Weaver/Hur Herald

|

Modeling the E&LK--A Narrow Gauge Smorgasbord

One aspect of the E&LK that differed from the majority of narrow gauge railroads was its variety. Although the primary purpose was to haul wood staves from saw mills it also managed to generate revenue by other means. The line also hauled raw timber as needed as well as serving the oil industry around Rosedale. As part of its agreement as a common carrier, it additionally hauled general freight and passengers between Gassaway and Shock. Its gateway to the world beyond was by two active connections with the Coal and Coke Railway--one at Gassaway and the other at Shadyside. All of these elements present a foundation for an interesting model potential.

One area that remains vague is the E&LK locomotive roster--both type and quantity. The photo above at Tague reveals a Shay and there is a reference to a Climax in the original research papers. How many of these locomotives were rostered is uncertain. But for the basis of a model railroad either or both will suffice. A standard locomotive-such as a 4-4-0 or 4-6-0--could traverse the grades pulling a coach or two between Gassaway and Shock. Freight cars would be flatcars with ends---early pulpwood cars hauling logs and staves--as well as a few narrow gauge boxcars, tank cars, and gondolas.

A freelancer could wield an unrestricted modeler's license with the E&LK. Build it as it existed 1909-1918 connecting to the Coal and Coke Railway---extend it into the 1920s and it interchanges with B&O. Then there is the north end---assume the Little Kanawha Syndicate completed its railroad from Parkersburg to Burnsville with the E&LK interchanging at or near Glenville. Another option would be converting the railroad to standard gauge from Gassaway to Shock. Endless are the possibilities.......

Afterword

In recalling the volume of information that exists within this piece it is an impressive testament to the amount of research that was conducted by those who blazed the trail before me on this railroad. Perhaps what is most noteworthy is the quantity of photographs that were taken along the Elk & Little Kanawha Railroad presented here and others that are known to exist. My ongoing mission will be to locate these images if they can be found. Photos of the area at Gassaway with the Coal and Coke Railway connection and the depots at Gassaway, Rosedale, and Shock would enhance this work immensely. Certainly, any other images taken along the route in addition to supplemental information will do likewise. At an undetermined date in the future additional contemporary images will be inserted as well.

Credits

Alex Brady

Annie Harvey Dulaney

"Gassaway and Community 1796-1942"

Dr. Tim Miller

Ron Miller

Smithsonian Institute

Phil Stevens

Harlan Stump

Robin Stump

Bob Weaver

West Virginia Economic and Geological Surveys

West Virginia Genealogy- History of Braxton County and Central West Virginia Chapter V

This humble effort is dedicated to the heretofore mentioned historians---Harlan Stump, Ron Miller, Bob Weaver, Annie Harvey Dulaney--living and in memoriam. It is also with thoughts of secondary contributors and the residents of Braxton, Gilmer, and Calhoun Counties.