Parkersburg to Clarksburg--Waist of the B&O Main

part ii

Although half of the tunnels were discussed in geographic sequence during the first part, Part II will begin by briefly detouring to a section devoted to the Parkersburg Branch tunnels as a collective group. A short segment about bridges will follow before continuing east to Clarksburg.

Tunnels

Locomotives passing through these bores created a heat inferno for the crews. During the steam era, a tunnel of sufficient length became a virtual hell. The heat, smoke, and cinders concentrated inside the bore resulted in almost unbearable conditions and the daylight that finally appeared at the end of the tunnel was a welcome relief. Three tunnels along the Branch were especially miserable and as a measure to relieve these conditions, B&O installed exhaust fans during the early 1900s. Not surprisingly, the tunnels were the original Number #1, Number #6 at West Union, and the original #21 at Eaton---the three longest. When trains reached the proximity of the bores, block operators activated the fans for their passage. These exhaust fans remained in service until the 1930s.

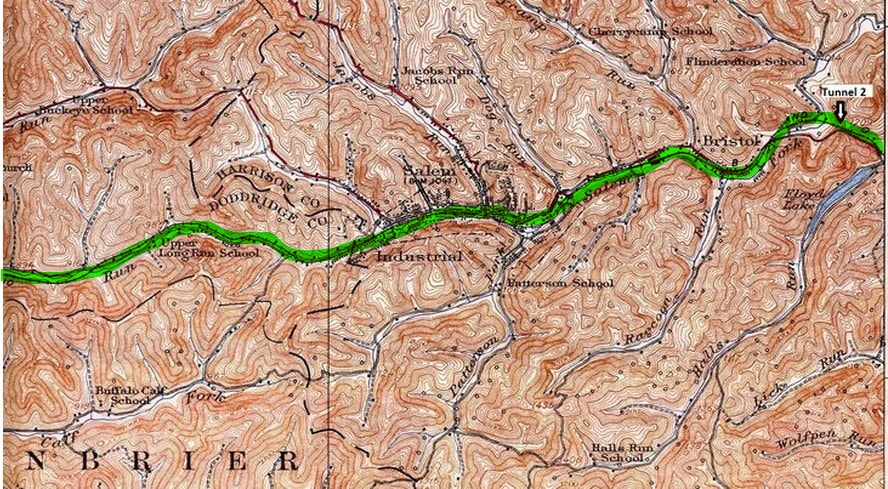

Tunnels by their sheer nature convey a mysterious aura. With the number that existed on the Parkersburg Branch, it is no surprise that at least two of them garnered a reputation through the generations for being "haunted". Tunnel l#2, also known as Brandy Gap or Flinderation Tunnel located near Bristol, is said to be occupied by apparitions of men struck by a train within many years ago. The most famous tunnel of lore is the previously discussed #19 at Silver Run. Whether one ascribes such sightings to the unexplained or dismisses them as legend, they certainly add spice to the mystique of the railroad.

Tunnels by their sheer nature convey a mysterious aura. With the number that existed on the Parkersburg Branch, it is no surprise that at least two of them garnered a reputation through the generations for being "haunted". Tunnel l#2, also known as Brandy Gap or Flinderation Tunnel located near Bristol, is said to be occupied by apparitions of men struck by a train within many years ago. The most famous tunnel of lore is the previously discussed #19 at Silver Run. Whether one ascribes such sightings to the unexplained or dismisses them as legend, they certainly add spice to the mystique of the railroad.

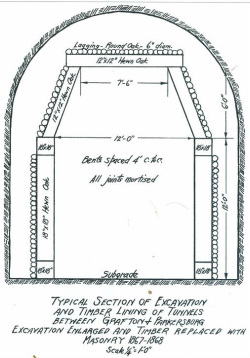

A template of the Parkersburg Branch tunnel specifications as built during the 1850s with timber lining. The arching was added during the late 1860s which not only improved stability but increased the operational clearances as well. Charlene Lattea-"North Bend Rail Trail: A Guide to the Trail and its History"

All sections of railroad rights of way have distinguishing features whether natural or man-made. Without question, the signature characteristic of the Parkersburg Branch was its 23 tunnels. Except for Tunnel # 1 between Clarksburg and Bridgeport, the other 22 were located on the 80 mile stretch between Parkersburg and Clarksburg, an average of one for every four miles. Of course they were not spaced that way. The majority were located on the western end of the Branch with the greatest concentration between Cairo and Pennsboro. When first constructed during the 1850s, all were lined with wood except for Tunnel #10. It was not until the aftermath of the Civil War that B&O relined them all (except #10) with bricked or stoned arching.

The lengths varied from the longest, the aforementioned Tunnel # 1 at 3236 feet--a 1952 concrete double track bore replacing the original 2708 foot one---to the shortest at 176 feet for Tunnel #11 east of Cornwallis. All were ultimately lined with stone or brick except for the new Tunnel#1, Tunnel #10 west of Ellenboro which was cut through rock and the new Eaton Tunnel #21 drilled in 1963 that was concrete lined. Two tunnels--Numbers 1 and 2---were the only ones tangent with the remaining twenty-one consisting of curvature of various radii. All had a horizontal width of between 14 and 15 feet except the replacement Tunnel #1 which was obviously wider (34 feet) accommodating double track.

Not only were the Branch tunnels numerically listed but most were also named. The numerical listing was the official method used by B&O in track charts and official reports but nowadays the names may be as familiar as the numbers on the North Bend Rail Trail. These names date to the construction of the line during the 1850s---the exception being Tunnel 10 which received an official second name in of honor of Dick Bias who was instrumental in the founding of the North Bend Rail Trail. Tunnels listed in red are ones replaced, bypassed or daylighted. The year(s) of construction are also noted.

Tunnel Number/Name Year(s) Constructed Comments

#1-Carr's (1853-1855) (also known as Lodgeville- single track bore) *

#2-Brandy Gap (1853-1854) (also known as Flinderation)

# 3 -Trough (1854)

# 4-Buckeye (1853-1854) (also known as Sherwood)

#5-Shannon (1854-1855)

#6-Doe Run (1853-1855) (also known as Central)

#7-Calhoun's (1855-1856)

#8-Cunningham's (1855-1856)

#9-Butcher's (1854-1855)

#10-Patterson's (1855) (renamed as Dick Bias NBRT)

#11-Teneriffe (1855)

#12-Section 71 (1853-1854)

#13-Bonds Creek (1853-1854)

#14-Section 72 (1853-1854)

#15-Unnamed (1853-1854)

#16-Section 73 (1853-1854)

#17-Unnamed (1853-1854)

#18-Section 74 (1853)

#19-Silver Run (1853-1855)

#20-Linn (1854-1855)

#21-Bee Tree (1853-1855) (original Eaton Tunnel bore)**

#22-Rodimer's (1853-1854)

#23-Farrell's (1853)

* Replaced in 1952 with double track bore

**Replaced in 1963 when original collapsed/known as Eatons Tunnel

**Replaced in 1963 when original collapsed/known as Eatons Tunnel

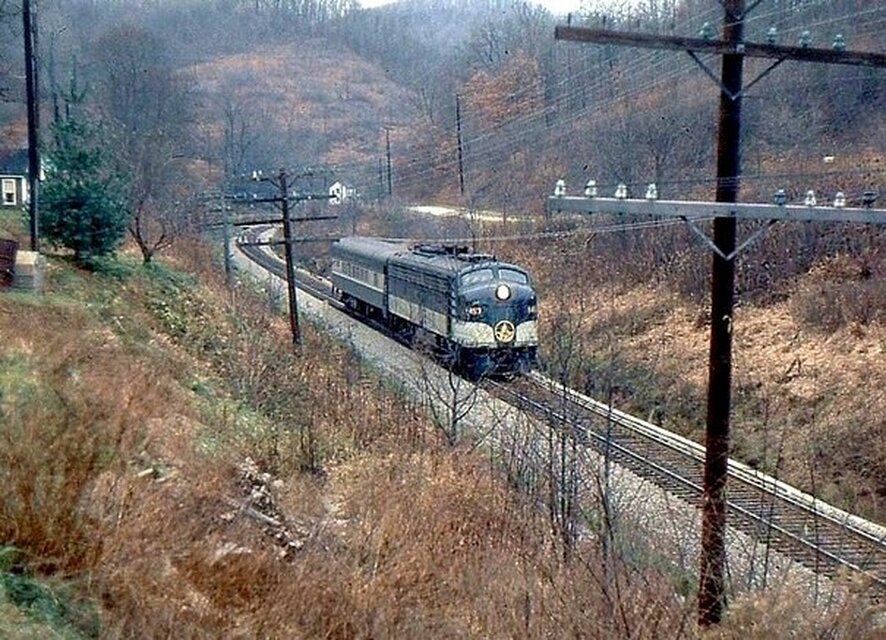

the 1963 Project

Once the C&O gained control of the financially ailing B&O, two steps were immediately taken to assist the Capitol Dome road on the road to recovery. An order for 77 new GP30 locomotives was placed with EMD in addition to transferring supplemental power and freight cars. Second and longer term was for B&O to enter the fledgling piggyback business (TOFC) in the Cincinnati and St. Louis markets. Unfortunately, B&O had been unable to move TOFC or higher cube boxcars over the Parkersburg Branch due to the restricting '14-"2 clearance of the tunnels on the route. If B&O were to compete using its strategically direct route to the Midwest, the clearance restrictions would have to be eliminated. In the spring of 1963, a plan was put into effect to increase the clearance to '17-"2.

The question about the plan was initially how to go about it. Keep the line open with traffic back-ups and curfews or shut it down completely? B&O President Jervis Langdon, Jr. weighed the options of each before rendering the decision to close the Parkersburg Branch completely and allow the work to be done uninterrupted. Beginning in April, the line was shut down sans work trains and traffic was rerouted between Parkersburg and Clarksburg via New Martinsville over the Short Line.

Between Parkersburg and Clarksburg there was a total of 21 tight clearance tunnels addressed on an individual basis. Tunnel 1 had been rebuilt as a double track bore a decade earlier in 1952 and Tunnel 23 no longer existed having been daylighted two decades earlier. Depending on factors such as topography above the bores, stability of rock strata, and tunnel length, the circumstances dictated what action would be undertaken at each location. Financial considerations also impacted and influenced the project to keep as economically practicable. When the tunnel clearance project was completed in the autumn of 1963, the tally was as follows:

It is interesting to speculate "what ifs" here. Had the engineers involved with this project known what lay ahead in the not too distant future, they assuredly would have increased the clearance another three feet through the remaining tunnels. Unfortunately, there was no crystal ball available. A yardstick may be the ironic footage that determined a route that---perhaps---would still exist today as opposed to one abandoned three decades ago.

The question about the plan was initially how to go about it. Keep the line open with traffic back-ups and curfews or shut it down completely? B&O President Jervis Langdon, Jr. weighed the options of each before rendering the decision to close the Parkersburg Branch completely and allow the work to be done uninterrupted. Beginning in April, the line was shut down sans work trains and traffic was rerouted between Parkersburg and Clarksburg via New Martinsville over the Short Line.

Between Parkersburg and Clarksburg there was a total of 21 tight clearance tunnels addressed on an individual basis. Tunnel 1 had been rebuilt as a double track bore a decade earlier in 1952 and Tunnel 23 no longer existed having been daylighted two decades earlier. Depending on factors such as topography above the bores, stability of rock strata, and tunnel length, the circumstances dictated what action would be undertaken at each location. Financial considerations also impacted and influenced the project to keep as economically practicable. When the tunnel clearance project was completed in the autumn of 1963, the tally was as follows:

- Floor lowered in five

- Roof raised in four

- Eight were daylighted into cuts

- Three were bypassed with cuts

- One new bore drilled to replace one that collapsed

- Five months to complete

- $8.5 million price tag

It is interesting to speculate "what ifs" here. Had the engineers involved with this project known what lay ahead in the not too distant future, they assuredly would have increased the clearance another three feet through the remaining tunnels. Unfortunately, there was no crystal ball available. A yardstick may be the ironic footage that determined a route that---perhaps---would still exist today as opposed to one abandoned three decades ago.

Parkersburg Branch Tunnels-II

|

Tunnel Milepost Length Location

1 299.6 3236 Clarksburg east

2 311.9 1086 Bristol east

3 321.4 282 Long Run west

4 322.0 846 Sherwood east

5 326.4 359 Smithburg west

6 330.2 2297 West Union west

7 340.3 780 Pennsboro east

8 342.2 588 Pennsboro west

9 343.0 855 Ellenboro east

10 348.8 377 Ellenboro west

11 349.9 176 Cornwallis east

12 350.5 577 Cornwallis east

13 351.0 352 Cornwallis east

14 351.7 182 Cornwallis west

15 352.2 478 Cornwallis west

16 352.4 220 Cornwallis west

17 352.8 452 Cairo east

18 353.3 963 Cairo east

19 356.9 1376 Silver Run

20 360.0 254 Petroleum east

21 364.5 1840 Eaton

22 365.7 338 Walker east

23 373.3 287 Kanawha

|

Comments

Double track bore-active CSX

Clearance increased B&O 1963

Bypassed with cut-B&O 1963

Clearance increased B&O 1963

Daylighted-B&O 1963

Clearance increased B&O 1963

Clearance increased B&O 1963

Clearance increased B&O 1963

Daylighted-B&O 1963

Clearance increased B&O 1963

Daylighted-B&O 1963

Clearance increased B&O 1963

Clearance increased B&O 1963

Daylighted-B&O 1963

Daylighted- B&O 1963

Daylighted-B&O 1963

Bypassed with cut-B&O 1963

Daylighted-B&O 1963

Clearance increased-B&O 1963

Daylighted-B&O 1963

Constructed new/original collapsed-B&O 1963

Bypassed with cut-B&O 1963

Daylighted-B&O 1943

|

Milepost locations are at the east portal of each tunnel

Ever since the abandonment of the Parkersburg Branch a topic of discussion has been what effect the tunnel work in 1963 had in regards to influencing that decision two decades later. Points of thought typically revolve around the Short Line as a viable alternative. It has been suggested that the Short Line proved its feasibility as a bypass when the tunnel work was in progress and thereby deemed the Branch as redundant. This is both true and false taken from the perspective of then and now. However, the true determiner here is neither the Branch nor the Short Line but instead, the mainline route across Ohio to Cincinnati.

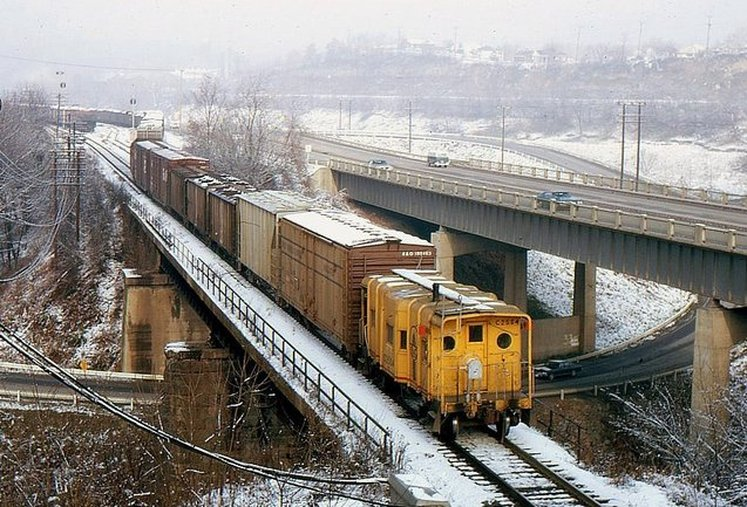

As an example, priority westbound freight CIN 97 detoured over the Short Line at Clarksburg to New Martinsville then south along the Ohio River before entering the Low Yard at Parkersburg. The train then had to pull up the transfer track connecting the Ohio River Line and the Parkersburg Branch and was actually facing east. The power would then have to be moved to the other end of the train before continuing west into Ohio. Not only did the detour add additional mileage but facilitated the moving of power at Parkersburg. Of course, the move would occur in reverse for eastbound trains. In essence, the Short Line bypass resulted in a bottleneck at Parkersburg.

Today, the Short Line as an alternative is a moot point since there is no more Parkersburg Branch or St. Louis mainline. CSXT scheduled trains Q316/Q317 run the route on a daily basis with blocks of cars for destinations between Clarksburg-New Martinsville- Russell, KY. These two Cumberland-Russell trains are the only scheduled manifests that operate on former B&O rails in northern West Virginia.

As an example, priority westbound freight CIN 97 detoured over the Short Line at Clarksburg to New Martinsville then south along the Ohio River before entering the Low Yard at Parkersburg. The train then had to pull up the transfer track connecting the Ohio River Line and the Parkersburg Branch and was actually facing east. The power would then have to be moved to the other end of the train before continuing west into Ohio. Not only did the detour add additional mileage but facilitated the moving of power at Parkersburg. Of course, the move would occur in reverse for eastbound trains. In essence, the Short Line bypass resulted in a bottleneck at Parkersburg.

Today, the Short Line as an alternative is a moot point since there is no more Parkersburg Branch or St. Louis mainline. CSXT scheduled trains Q316/Q317 run the route on a daily basis with blocks of cars for destinations between Clarksburg-New Martinsville- Russell, KY. These two Cumberland-Russell trains are the only scheduled manifests that operate on former B&O rails in northern West Virginia.

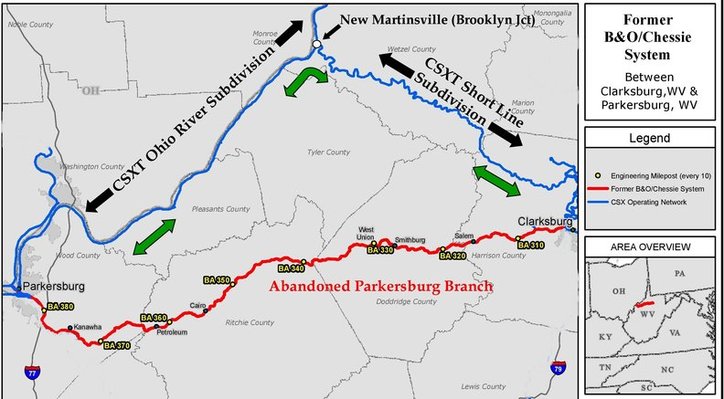

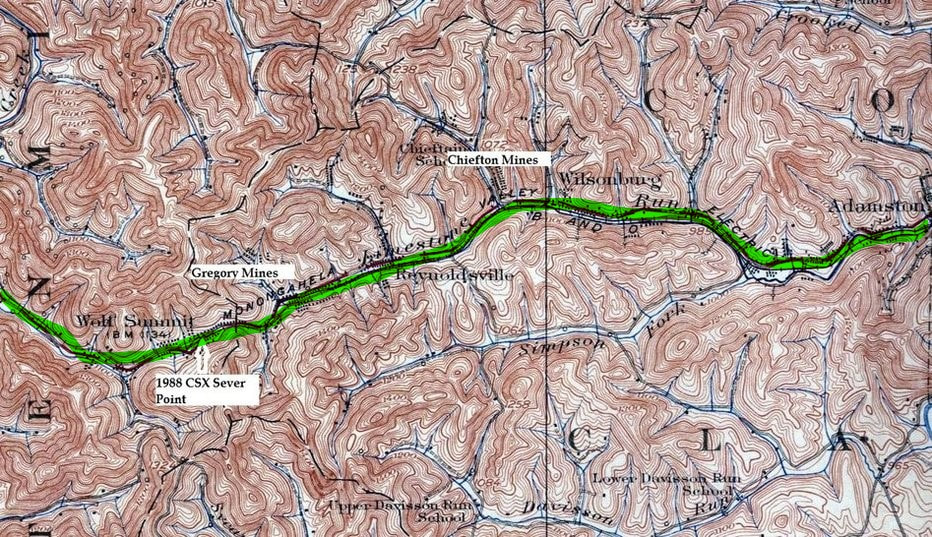

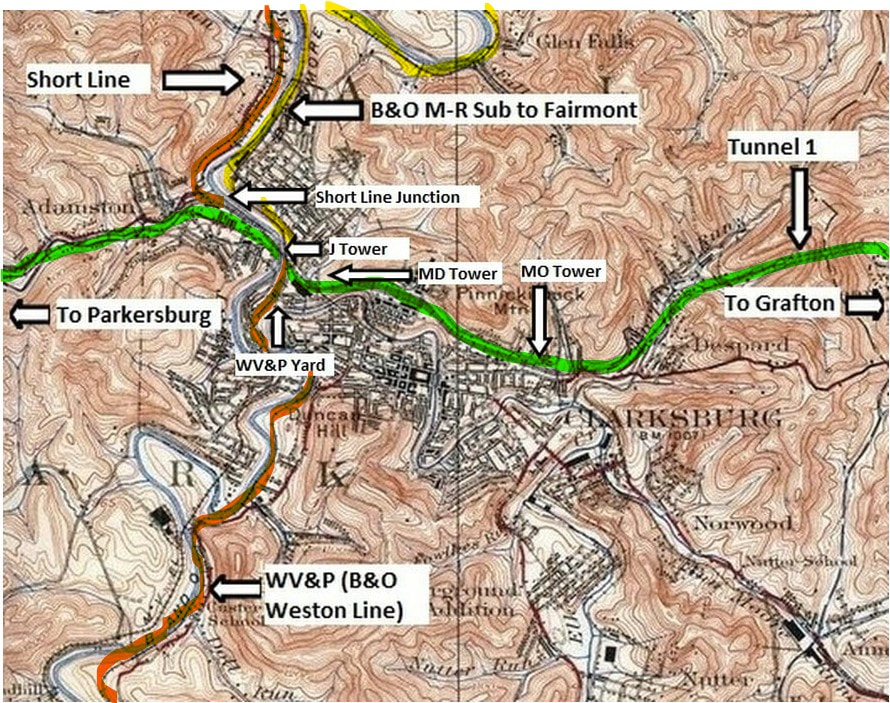

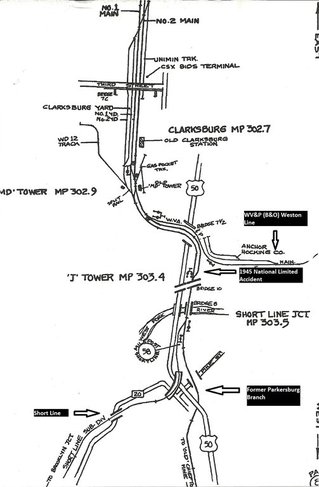

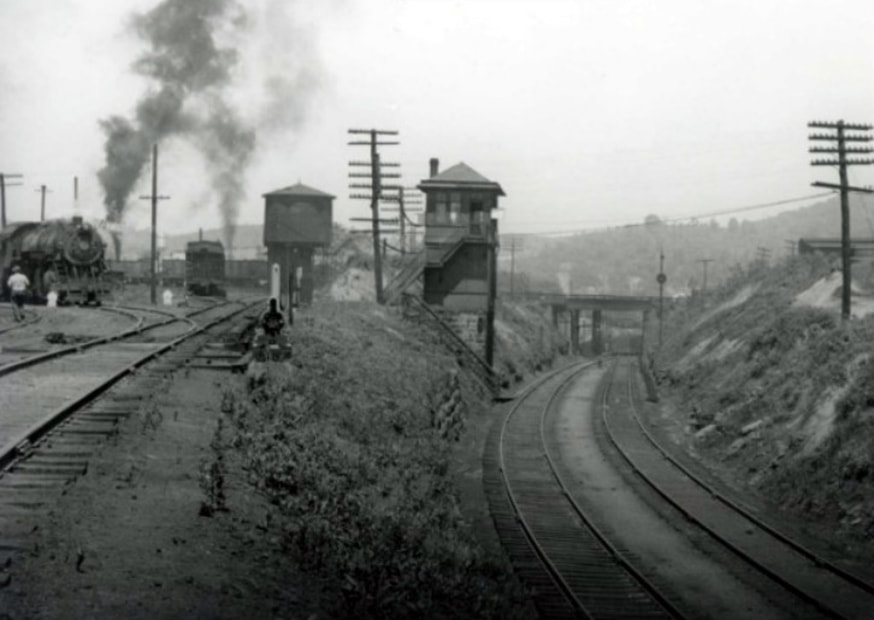

This map outlines the detour of trains over the Short Line and Ohio River Line during the 1963 tunnel clearance project. The reroute increased mileage between Parkersburg and Clarksburg and required additional moves at Parkersburg. CSXT trains Q316 and Q317 use this route today. Map courtesy of CSXT Engineering/ overlay Dan Robie.

The tunnels today are silent except for the passage of hikers and bikers along the North Bend Rail Trail unless one includes the sights and sounds of the unexplained as reported by some. They have remained in remarkably good condition as far as the linings go but are prone to standing water. When track was inside the bores, ballast kept the ties and rail above the floor thereby reducing the effects of moisture.

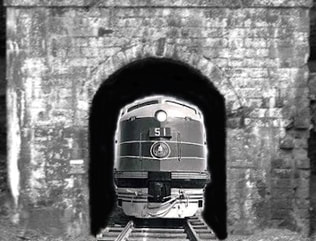

From a visual standpoint, there appears to be noticeable differences among the group in terms of the height, width, and portal openings. Of course, several portals were reconstructed during the 1963 project when the faces were reworked and brick facades added. At minimum, all achieved the '17-"2 overhead clearance but several appear larger to the naked eye. An observation is that the stone portal tunnels east of Pennsboro project a narrower width.

From a visual standpoint, there appears to be noticeable differences among the group in terms of the height, width, and portal openings. Of course, several portals were reconstructed during the 1963 project when the faces were reworked and brick facades added. At minimum, all achieved the '17-"2 overhead clearance but several appear larger to the naked eye. An observation is that the stone portal tunnels east of Pennsboro project a narrower width.

Bridges

The majority of bridges along the Parkersburg Branch were of deck plate and truss construction spanning the numerous small creek crossings along the route with none exceptionally long or massive in structure. These either have standing piers or are built upon arched understructure. Bridge #23 at West Union crossing both Middle Island Creek and WV Route 18 is the most impressive of this type of structure. Girder plate bridges were also used at such locations as Bridge #36 over the North Fork Hughes River at Cairo and Bridge #22 spanning Middle Island Creek at West Union. The one example of an elevated truss is an exceptional one---#53, the Ohio River bridge at Parkersburg---which also uses decked approaches.

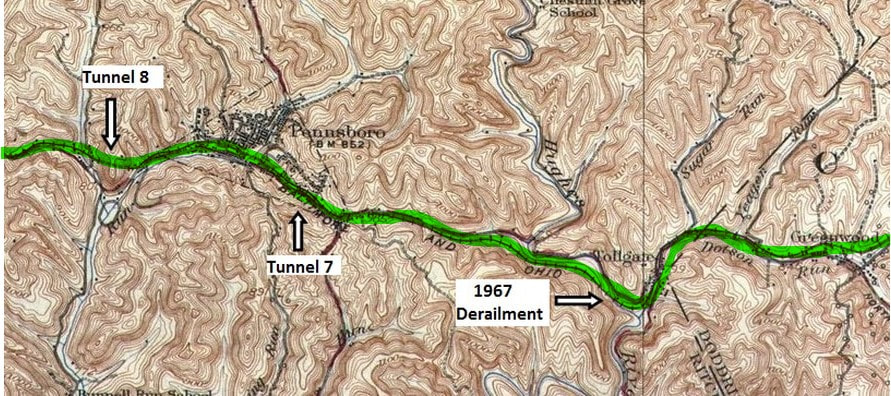

Pennsboro to Greenwood

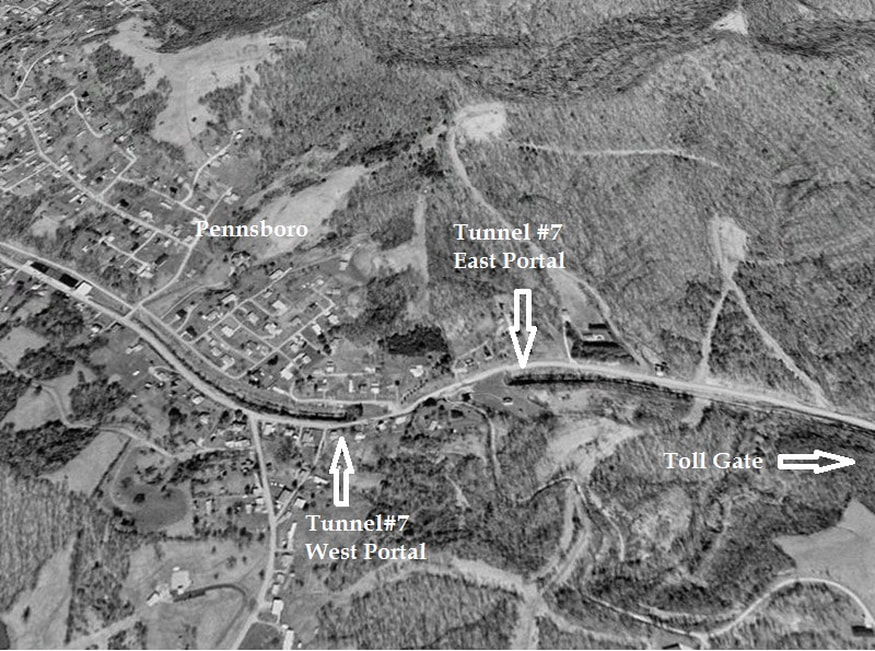

This 1924 topo map is of the mid-point between Parkersburg and Clarksburg. Pennsboro is at the heart with two tunnels flanked at each end and the railroad briefly touches the Hughes River at Toll Gate before crossing into Doddridge County. The line then follows the Dotson Run drainage into Greenwood.

Just as Pennsboro is the halfway point on the railroad between Parkersburg and Clarksburg, so shall it begin Part II of this of this eastward trip along the Branch. Tunnel 8 is the west gateway to the town and B&O did as much passing through the 588 foot bore to reach the town.

|

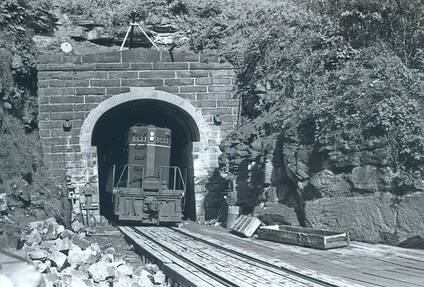

Tunnel #8 during the 1963 work. Note the wood planking and work on the portal itself. B&O GP9 #6533 is an interesting sight in the bore that does not appear to have been enlarged yet. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

|

Fifty years later, a snow covered entrance to the west portal of Tunnel #8 located at the west end of Pennsboro. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

|

A 1996 Google Earth view of the region of Tunnel #8. Also known as Cunningham's Tunnel, it is situated on a curve at the western end of Pennsboro with a length of 588 feet. The North Bend Rails to Trails Foundation has stated that this tunnel is overlooked by the public more than any other along the rail trail.

Pennsboro

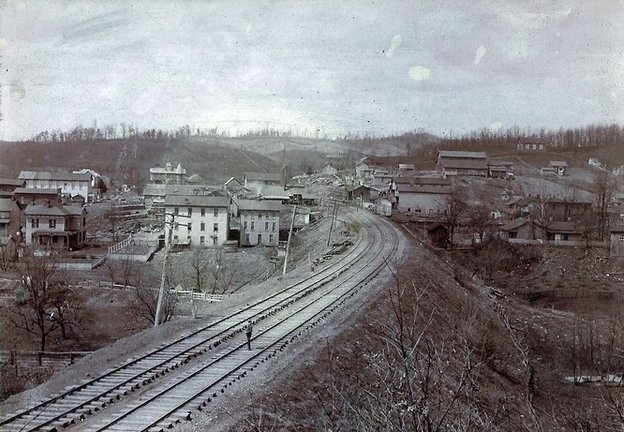

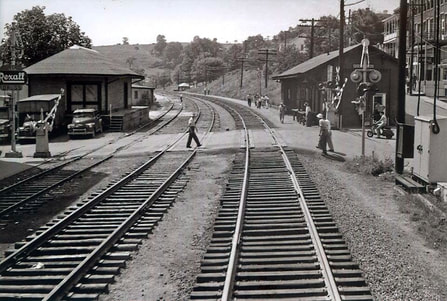

From a historical perspective, a considerable number of photographs were taken at Pennsboro and especially during the early 1900s. In terms of quantity, there are more collection images at this location than any other along the railroad between Parkersburg and Clarksburg.

This remarkable photograph at Pennsboro circa 1915 captures the town and railroad in full glory. A special event, perhaps the county fair or a holiday parade, has attracted a large crowd of people. The photographer positioned atop a boxcar captured the atmosphere of the moment in this view that looks westbound. How the world has changed--people wore their "Sunday best" to virtually every social event and spectators standing on a railroad track would be quickly dispersed today. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

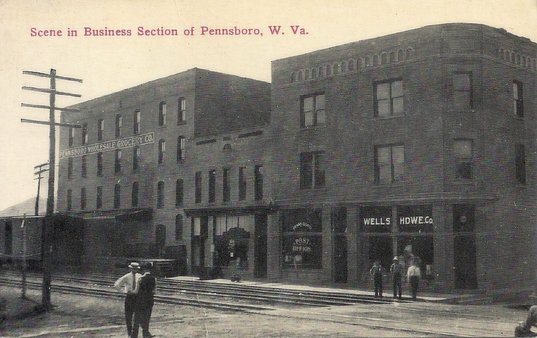

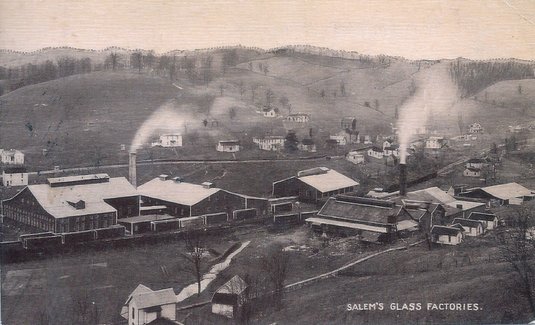

Of all the shippers once located in the smaller towns along the Parkersburg Branch, glass manufacturing was the pre-eminent industry. Two such businesses existed at Pennsboro during the early 20th century represented by the Penn Window Company and the Premier Glass Company.

The significance of Pennsboro extends beyond that of a central location along the line between Parkersburg and Clarksburg. Of all the towns between the two end points, it was of more commercial importance as there was a larger quantity of on-line shippers located here. Especially notable during its early history was the glass industry represented by the Premier Glass Company and Penn Window Glass Company. It was also the junction of a short line narrow gauge railroad that ran to Harrisville in addition to a prominent passenger stop for B&O. In fact, Pennsboro remained on the timetable until April 30, 1971, when both the eastbound and westbound Metropolitans made their final stops.

|

This view looking west through Pennsboro is undated but appears to be circa 1890s. The depot can be seen at center but the large structures that would occupy the trackside area at left have not yet been built. B&O telegraph poles are on the south side of the tracks---they would later be relocated to the north side. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

|

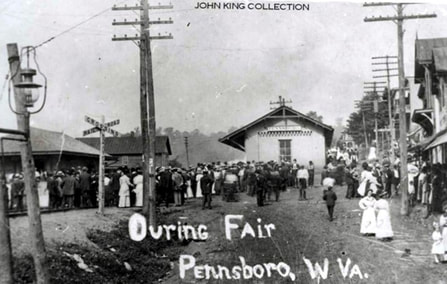

Another image that captures the festive atmosphere that was Pennsboro at county fair time circa 1910. Taken from the east side of the depot, a crowd swarms the railroad as others move about on the town streets. Although county fairs remain popular today, they were a major event in bygone years when entertainment and social attractions were substantially less. Image Dan Robie/John G. King collection

|

For the majority of the 1900s, Pennsboro was a center of social activity in Ritchie County. The county fair, the first established in West Virginia, was among the largest and festive in the state and attracted large numbers of people each September. On the west end of town was the Pennsboro race track that initially hosted horse racing but transitioned to auto racing in later years. These events increased passenger train travel on the B&O and the P&H (Pennsboro & Harrisville Railroad) from Harrisville to Pennsboro.

|

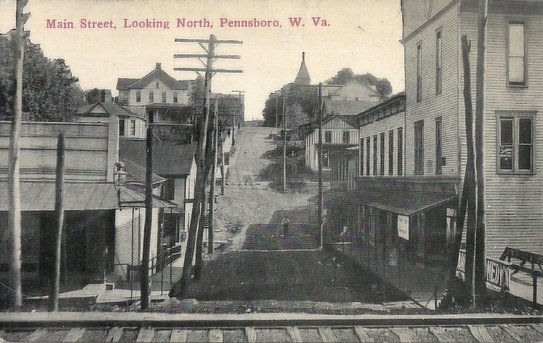

Early 1900s view of Main Street from the railroad. Turn of the century Pennsboro was at its zenith in accordance with the railroad during this era. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

|

This photo was taken from the railroad depot looking eastward across the tracks. The Pennsboro Wholesale Grocery is clearly visible in this early 1900s scene. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

|

In 1875, a narrow gauge railroad was constructed from Pennsboro to the county seat at Harrisville. Initially known as the P&H (Pennsboro & Harrisville Railroad), the small line provided a vital connection for the residents and businesses of Harrisville to the B&O mainline. Fulfilling a valuable niche, this small railroad remained in existence for forty years and during its life span, was one of two railroads serving Harrisville with a B&O connection. The other, of course, was the Harrisville Southern previously mentioned that connected with B&O at Cornwallis.

|

A colorized postcard of the railroad heart of Pennsboro from 1908. View is westbound. Image courtesy Blackwood Associates

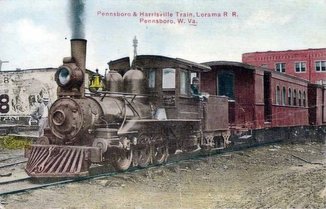

A narrow gauge P&H (Lorama) Railroad train at Pennsboro in its heyday circa 1905. Image courtesy Ritchie County Historical Society

|

B&O steam action near Pennsboro circa 1910. Location not specified but appears to be on the line between Pennsboro and Toll Gate. Image courtesy Ritchie County Historical Society

|

In 1902, the P&H fell under new ownership and was rechristened the Lorama Railroad. The little line achieved its peak during this era hauling freight and passengers between Harrisville and Pennsboro with an extension constructed to the town of Pullman. The Lorama would run special reserved trains for the residents of Pennsboro to access the Hughes River for recreational purposes. In summer, it was swimming parties and in winter, groups for ice skating.

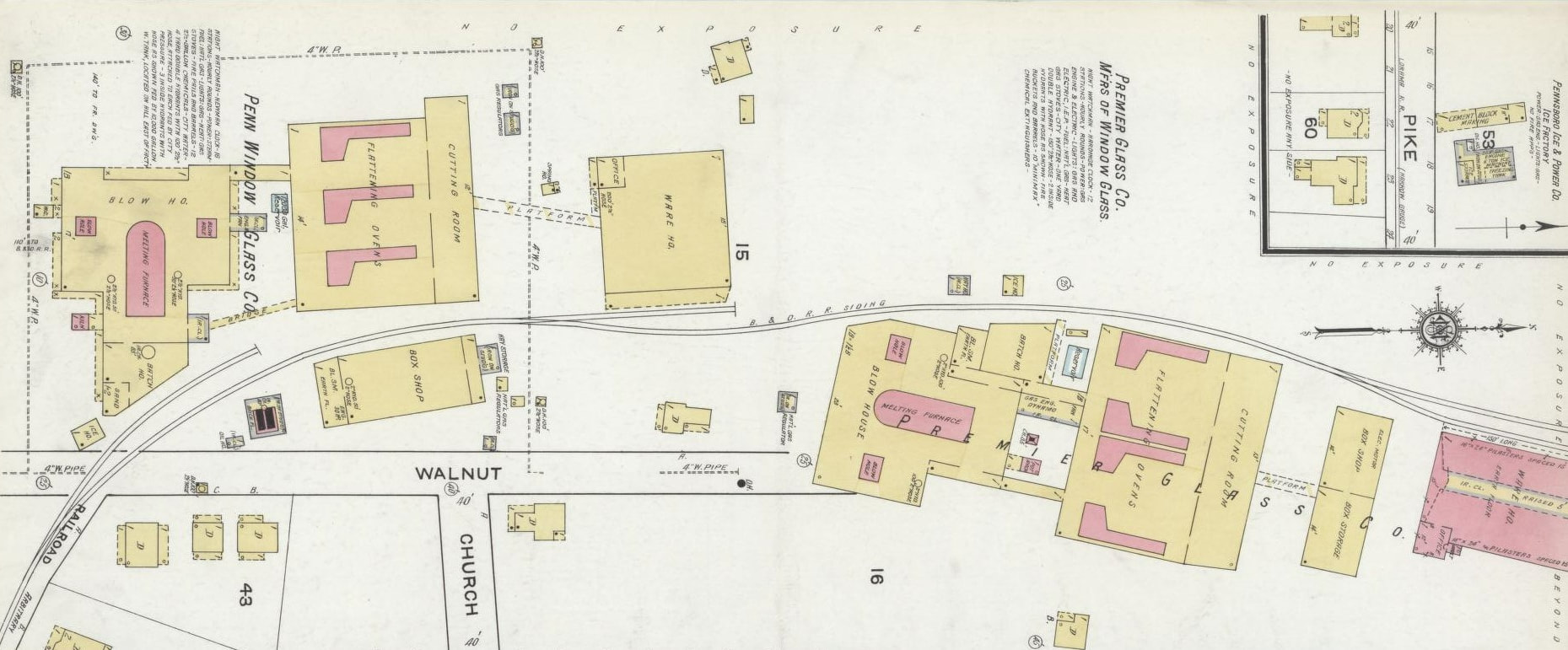

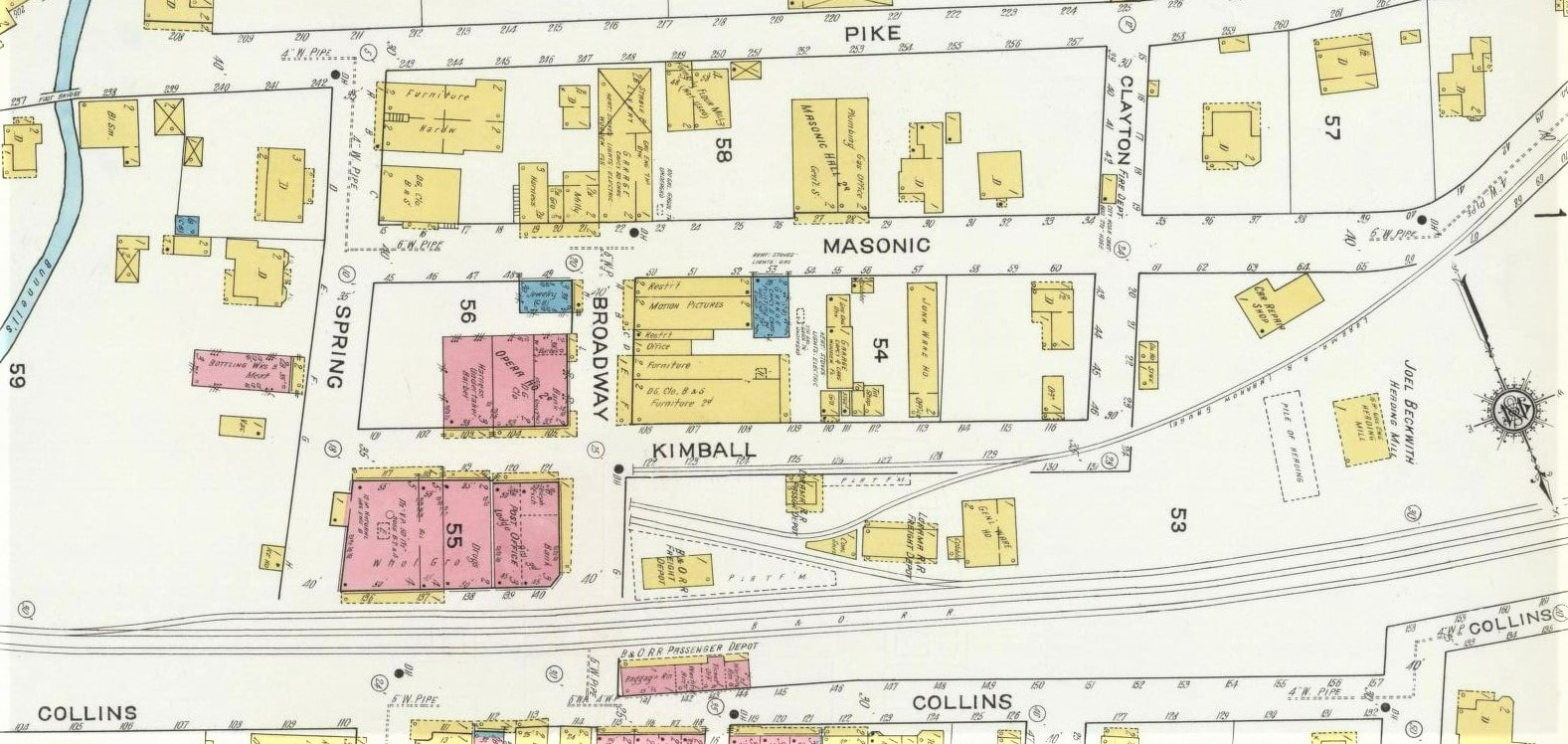

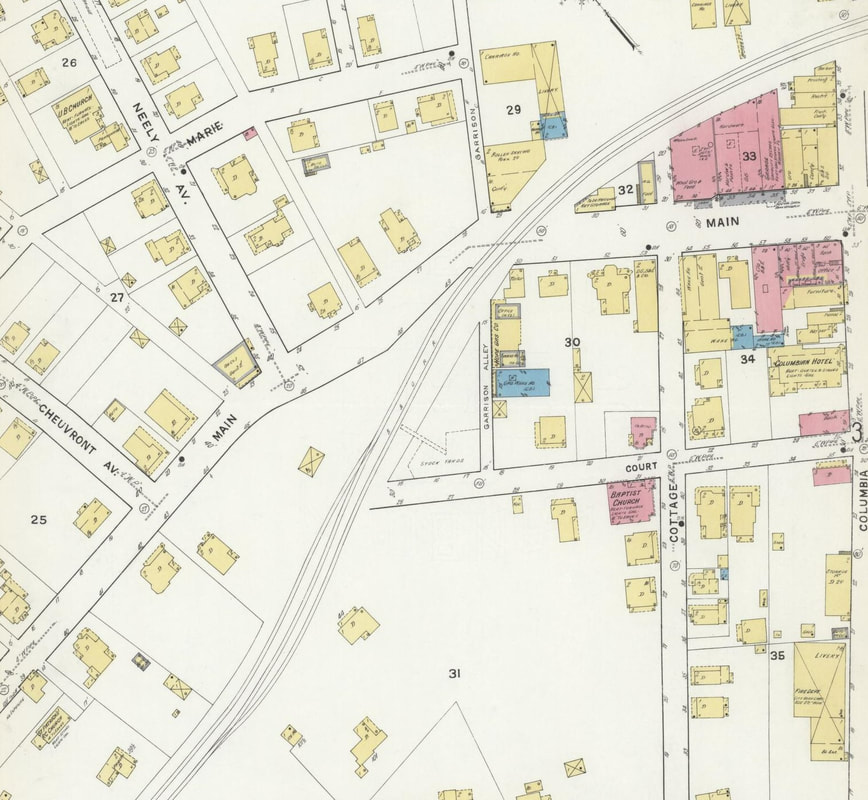

The heart of Pennsboro as it was depicted in 1916. Both the B&O passenger and freight stations sat opposite of each other along the main line and sidings. Of particular interest is Pennsboro & Harrisville RR (Lorama) depot and its orientation to the B&O. Note that the narrow-gauge line had no direct connection to B&O--passengers and freight transferred from one line to the other.

By the 1920s, automobiles and trucks on an improving road system wrought extinction for the Lorama just as with the other short line railroads in the region. In an ironic twist of fate, the Lorama Railroad near the end of its existence hauled gravel to Harrisville for the construction of the very roads that would seal its doom. The demise of the small railroads ended a colorful chapter in Ritchie County history.

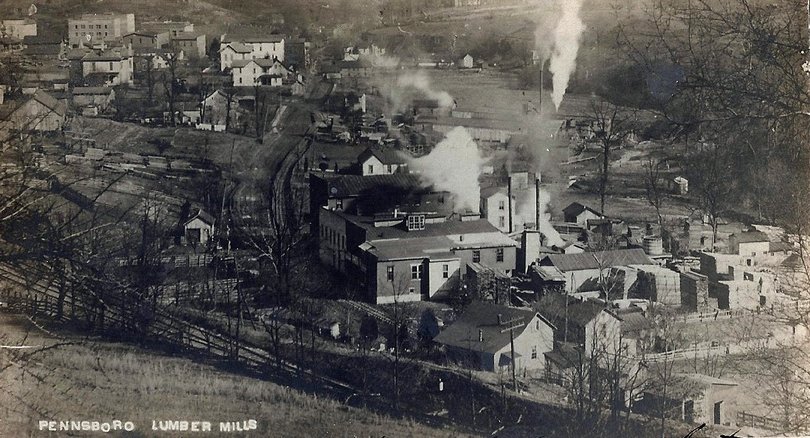

The Parkersburg Branch was populated with small to medium sized shippers during the early 20th century. One such business was the Pennsboro Lumber Mills pictured here looking east through town circa 1920s. By the World War II era, most of these shippers had passed into history. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

Pennsboro was the location for a block station (B&O call letters NR) until it was replaced by CTC in 1951. The passing siding was conventional rather than lapped and remained active through the final years of the railroad. B&O served various shippers at Pennsboro throughout the years and it still listed five as active in 1948: Tom Jackson Company, Pennsboro Feed Company, Pennsboro Grocery Company, J.R Broadwater and the Triple Oil Company. All were gone by 1970.

|

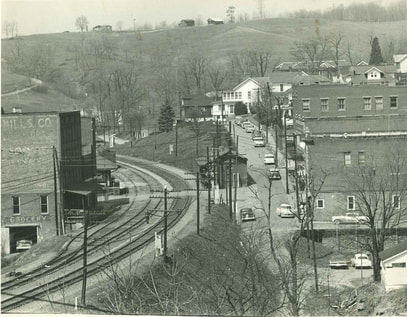

A westbound view from the EUB church overlooking Pennsboro circa early 1950s. The National Limited and Diplomat were still operating and trains such as the Metropolitan Special called at the depot seen in the curve at right. At left the siding is still in use for the Pennsboro Grocery Company and other shippers. At this date the trackside observer witnessed a good mix of steam and early diesel power such as E units on passenger trains and FT, F3, and F7 models on the priority freights. Image courtesy Ritchie County Historical Society.

|

Train time in circa 1960 Pennsboro. As Train #12, the Metropolitan Special, departs on its eastward journey, the view from the rear captures the moment after it clears. Passengers that disembarked on the station walkway, the raising crossing gates, and people crossing the tracks. A good view of both the Pennsboro freight and passenger depots along with the Rexall Drugs sign and period vehicles. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation.

|

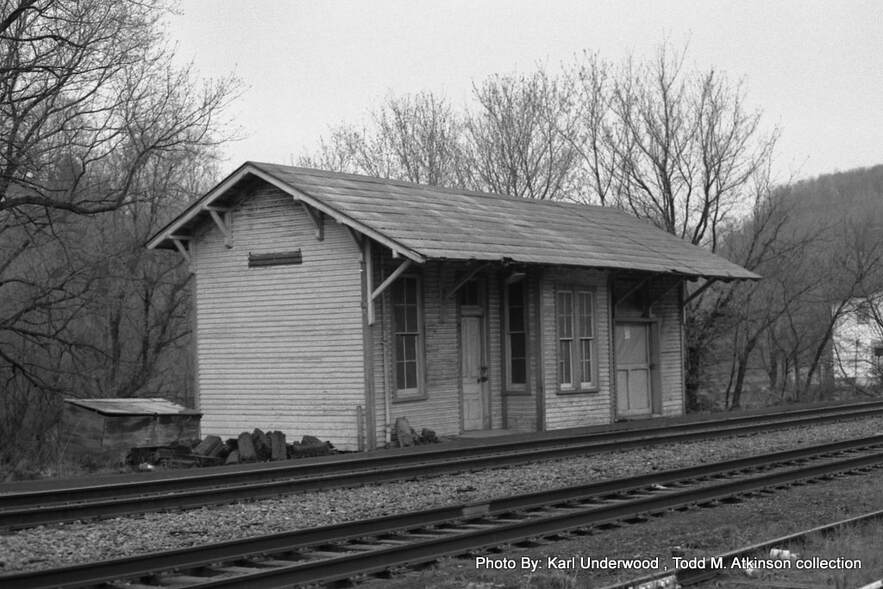

The Pennsboro depot as it appeared in 1978. It had been seven years since the last passenger train called here with the eastbound Metropolitan Special making its final stop on April 30, 1971. Amtrak Shenandoah Trains #32 and #33 simply passed by on their daily runs when this photo was taken. Seven years hence, there would be no more trains passing at all. Image Karl Underwood/Todd M. Atkinson collection

Pennsboro...1990s

|

The Pennsboro depot as it appeared in 1992, four years after the track was removed. The interim period between abandonment and restoration of the structure and Rail Trail. Dan Robie 1992

|

Eastbound view along the right of way. The old Pennsboro Grocery building still stands at right and the EUB church is a long time landmark on the hill. Dan Robie 1992

|

Lasting into the Chessie System era, Pennsboro remained a station point for maintenance of way employees because of its strategic position along the route. After the mainline was downgraded in 1985, jobs were obviously eliminated here as well as other locations associated with the Parkersburg Branch.

|

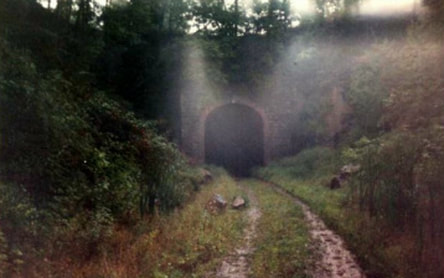

A misty view looking at the east portal of Tunnel #7 on the east end of town. Dan Robie 1992

|

Eastbound view of the right of way from near Tunnel #7 facing towards Toll Gate. Dan Robie 1992

|

As Pennsboro is flanked by a tunnel on either end of town, Tunnel #7 is the bookend on the eastern end. Named Calhoun's Tunnel, it was constructed on a curve at 780 feet in length. Visually deceiving, the portals and clearance look lower on this bore than any other along the Parkersburg Branch in this observer's opinion. Old US Route 50 and private property occupy the hill above it. Fortunately, B&O was able to enlarge the bore for those reasons alone.

Toll Gate

A 1996 Google Earth view of the Toll Gate area. The railroad right of way crosses Bridge #26 over the North Fork Hughes River and enters on a sweeping curve into the community. At right the general location of the Toll Gate Pipe Yard from yesteryear is indicated as well. For the rail photographer, the road from four lane US Route 50 leading to the town would have afforded a panoramic angle of trains in the curve.

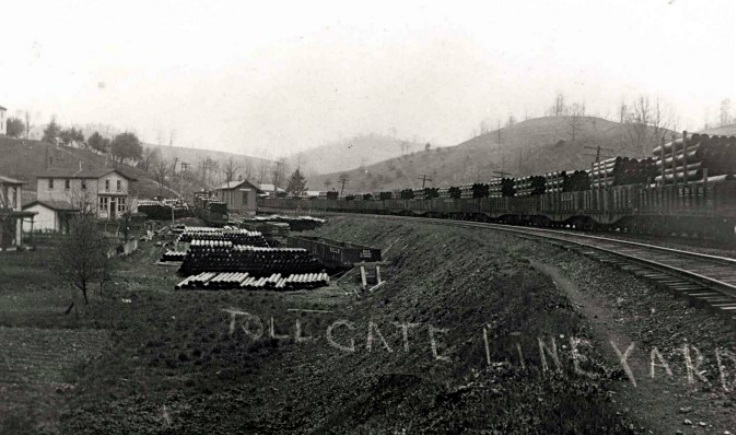

Another of the colorful town names along the Parkersburg Branch is for the small hamlet of Toll Gate. The origin of the name dates to the 1840s when this location was a toll collection point along the Northwestern Turnpike. As a toll gate along the route, it was referred to as Toll Gate and the name stuck for this unincorporated community. Although it straddles the Ritchie-Doddridge County border, it is predominately within the limits of Ritchie.

A relief train cleans up the mess from a derailment circa 1930s. The photo caption indicates the location was at the US Route 50 bridge which would be the east end of town. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

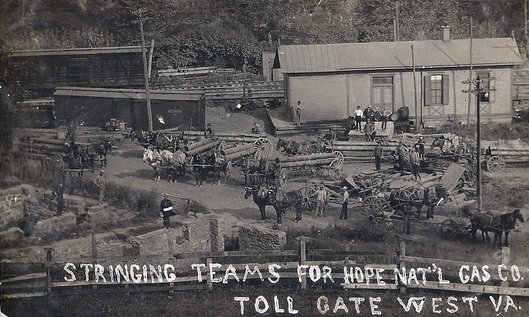

Located along a sharp bend in the Hughes River, the railroad paralleled the stream on a broad sweeping curve with only a slight tangent located near the US Route 50 grade crossing. Situated along this bend, Toll Gate contained a railroad depot and was the location for the Toll Gate Line Yard owned by the Hope Natural Gas Company which was a large operation. This yard was located to the west of the depot and was a busy industry during the oil boom years of the early 20th century. I could find no record of when this business ceased but it was gone by the World War II era. B&O did not list it or Hope Natural Gas as a rail shipper at Toll Gate as of 1948 so it evidently vanished with the oil boom.

These excellent trackside views preserve for posterity how Toll Gate appeared during the oil boom era of the early 1900s. The pipe yard was a thriving enterprise supplying material for the booming oil industry and the eastbound views also capture the town, depot, and the curve of the railroad. Images Dan Robie/John G. King collection

Not unlike other small communities along the Parkersburg Branch, Toll Gate was relegated to a sleepy village when the oil boom subsided by the 1920s. It disappeared as a scheduled timetable stop as the number of passenger trains decreased with the passing years. It did, however, remain as a flag stop for the West Virginian at least until 1959.

|

A close up view of the Toll Gate depot in its full glory circa 1920. Quite a bit of freight on the platform this day in addition to serving as the whistle stop for passengers. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society

|

An image loaded with detail. Crews with teams of horses and pipe wagons leave the depot en route to drilling operations in the field. A boxcar and stock car add to the scene as well as the close up of the Toll Gate depot. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

|

Toll Gate was the site of several recorded derailments throughout the history of the Parkersburg Branch but perhaps none more tragic than the one that occurred on February 24, 1967. Train #31, the remnant of the National Limited, was transporting among its passengers this day a high school basketball team and students from Martinsburg to Huntington for a game. This derailment resulted in four fatalities and fifty injuries of varying degrees.

The investigation determined that at 6:43 AM as Train #31 swept westward at 43 MPH through the curve at Toll Gate, a rail overturned on the approach to the Hughes River Bridge. Four diesel units, F7A #4467, GP9 #6475, GP9 #6444, and E8 #1441 were the power on this five car passenger consist. The locomotives and first car remained upright but the second, third, and fourth cars overturned. The last car, named Wabash River, completely detached from the fourth car and plunged onto the east bank of the Hughes River. B&O was found to be at fault for the cause of this derailment. It was determined that the rail was improperly maintained for lack of elevation and securement. After this accident, the railroad was ordered to inspect all curves.

Toll Gate was the scene of yet another derailment in 1972. This series of photos offers glimpses of a TOFC train, likely the Manhattan or St. Louis Trailer Train, that left the rails spilling cars onto US Route 50 below. Details of this accident are scant---what is apparent is that it is winter with the leafless trees and the cold may have caused a broken rail leading to the derailment. A work train was dispatched from Grafton including a "big hook"--a crane to pickup and rerail cars. Images courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society

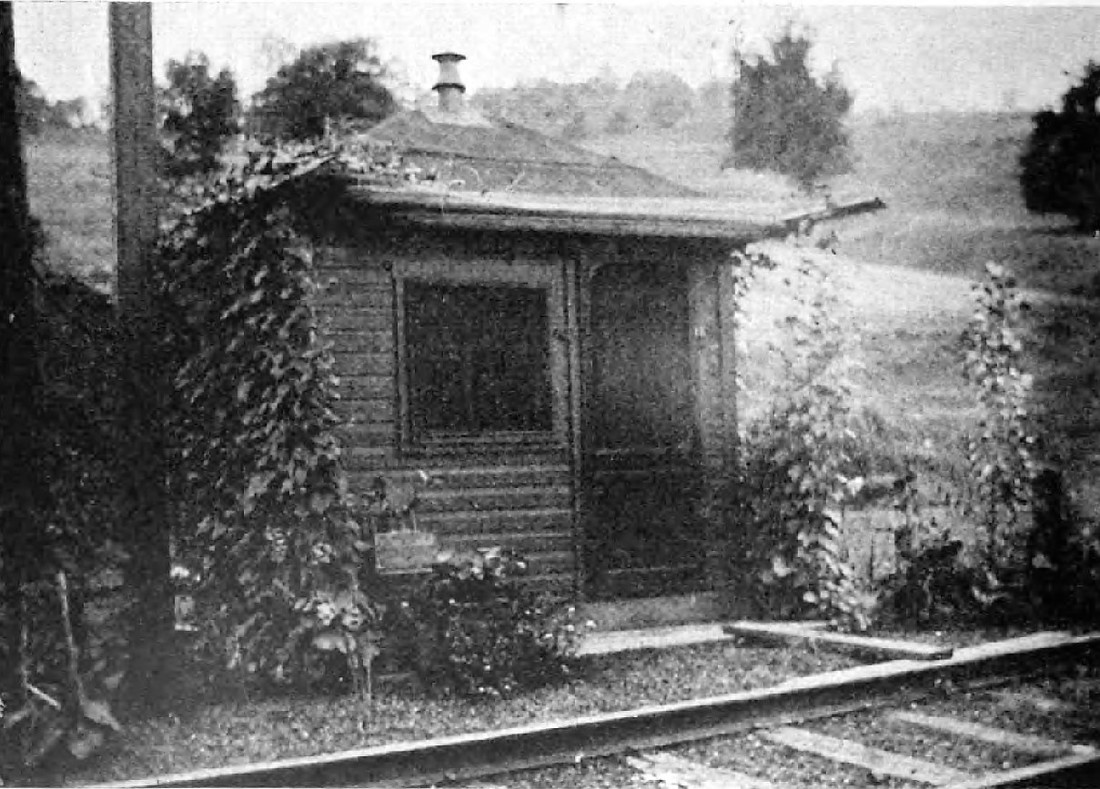

Greenwood

The railroad continued to parallel Dotson Run as it crossed over into Doddridge County entering the community of Greenwood. This location was a minor name location along the B&O in regards to shippers. In fact, it did not construct a passenger depot here, either. Instead, it opted to use a store with an agent to suffice for the function of an actual depot. Greenwood existed as a stop for many years and was listed as a flag stop as late as 1959 for Trains #23 and #30, the West Virginian. In reality, it lasted longer. Prior to the tragic 1967 National Limited derailment at Toll Gate described previously, the investigative report noted that a passenger fatefully deboarded the train at Greenwood minutes before the accident.

Eastbound view of the B&O at Greenwood during the early 1900s. There were two existing general stores at Greenwood early in the century---Jasper Bond and Mathias C. Young ---the latter which shared the passenger platform in the photo. Looks like a single passenger awaits a train this day. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society.

The good citizens of Greenwood did not give up their battle for a depot without a fight. In 1915, they petitioned the ICC to order the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to construct a depot in the community but to no avail. B&O countered by stating that the facility in use---the store with an agent--was adequate. As a consequence, Greenwood never realized a true railroad depot of its own although a small shed was later constructed to serve in that capacity. During this same era, Greenwood had both a flour mill and a livestock yard. Whether these two businesses were railroad shippers is not recorded but the probability is that they were. B&O listed no shippers of record at Greenwood by 1948.

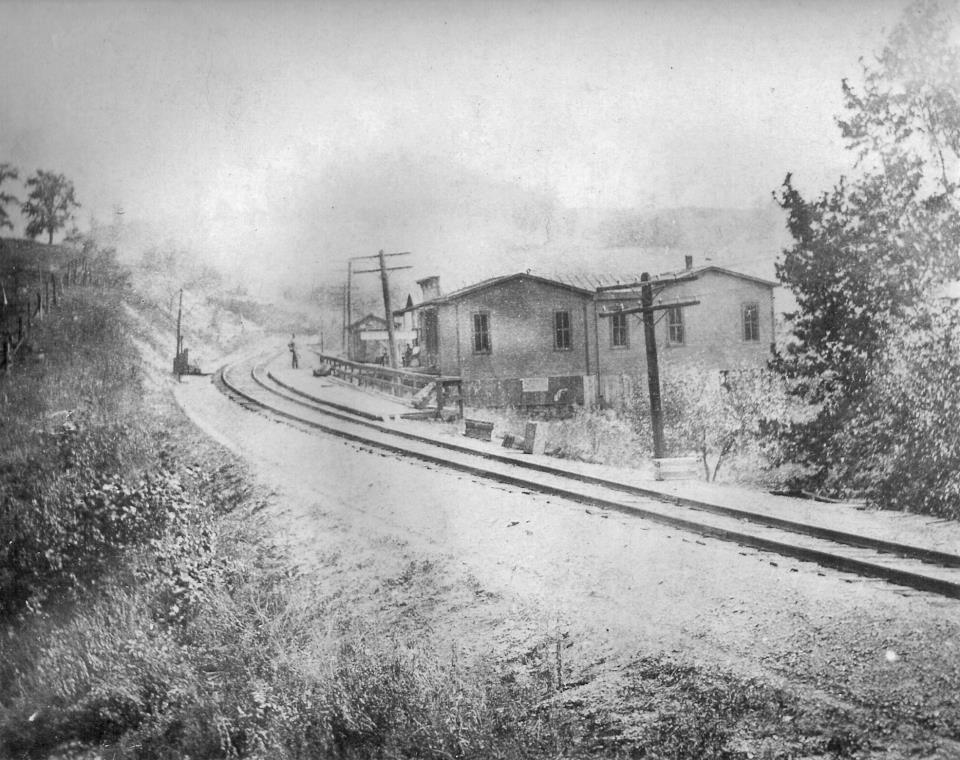

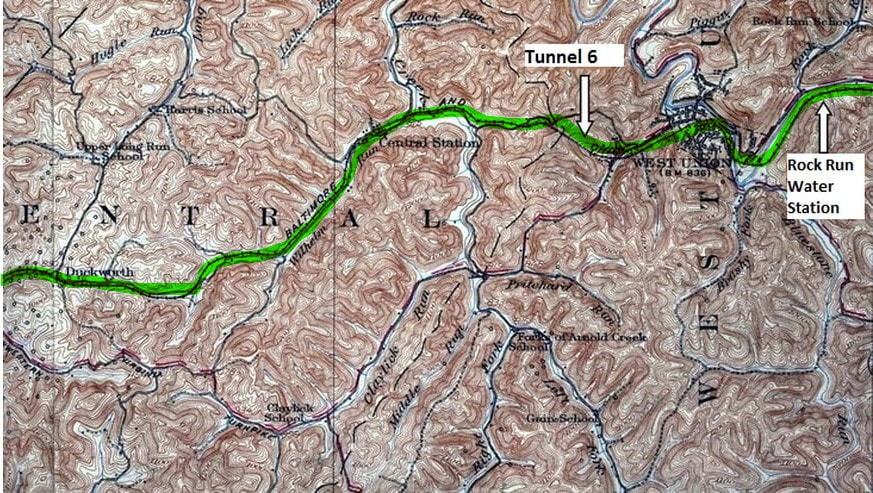

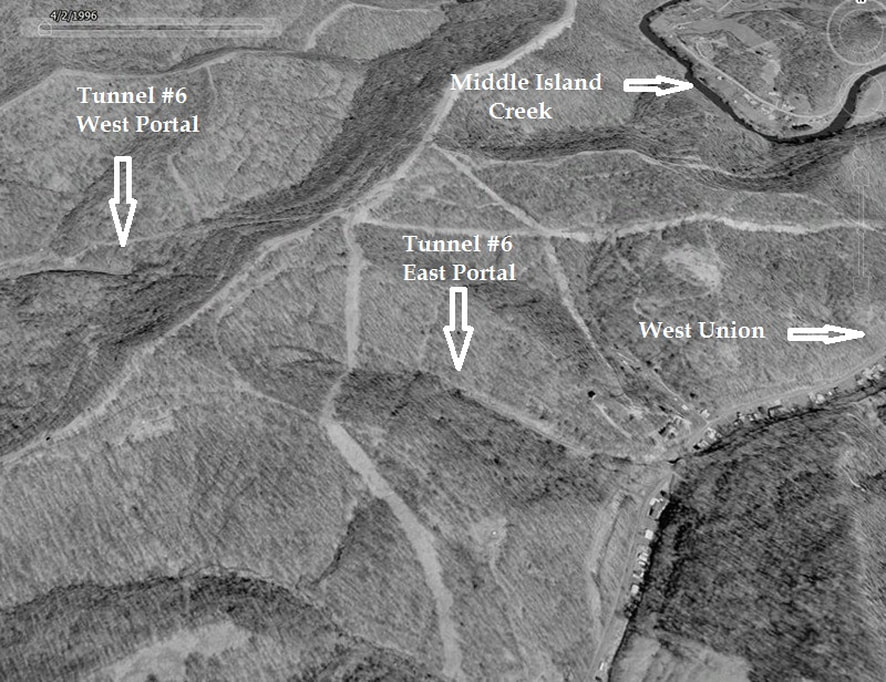

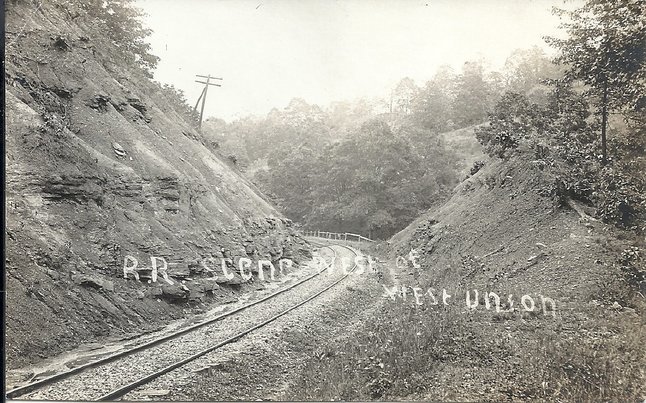

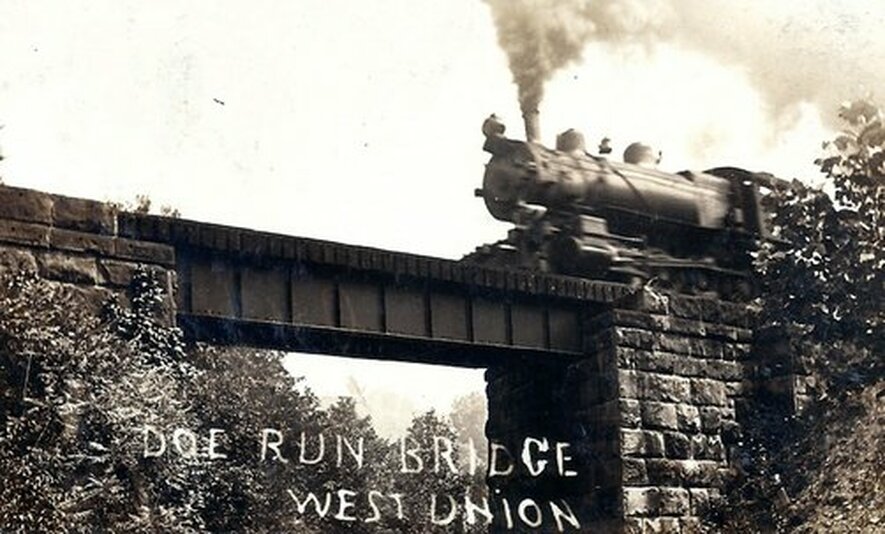

Duckworth to West Union

The B&O crossed into Doddridge County through Duckworth before following Wilhelm Run to Central Station. From this point, the line crossed the divide through the 2297 foot long Tunnel 6 into the Middle Island Creek basin at West Union. A reverse "S" curve defined the railroad as it swept through West Union to cross Middle Island Creek twice and thereafter paralleling it.

Duckworth

This small community was of no commercial importance to B&O by the 1940s but was significant operationally. A lapped passing siding was located here and remained in active service until the route was closed in 1985. Duckworth did not appear on any railroad timetables dating from the World War II era even to the extent of a flag stop. If any scheduled trains stopped at the location, it was eliminated during the early 1900s.

This 1975 image of a westbound coal train at Duckworth is among the late Art Markley's finest. Everything about this scene is special--a rarely photographed location, the Chessie paint amidst the hued greenery, and a wonderfully bucolic setting. Simply an outstanding photograph that is vintage B&O Parkersburg Branch and West Virginia countryside. Image courtesy Dave Dupler/Art Markley collection

|

Concrete remains of the block station at Duckworth. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

|

The rusted remains of a CPL mast alongside the right of way at Duckworth. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

|

From what I can determine, Duckworth was the only block location along the Parkersburg Branch that was not a telegraph office. It was manned only by an operator for the function of controlling the passing sidings. Once CTC was implemented, the location was controlled remotely from Grafton.

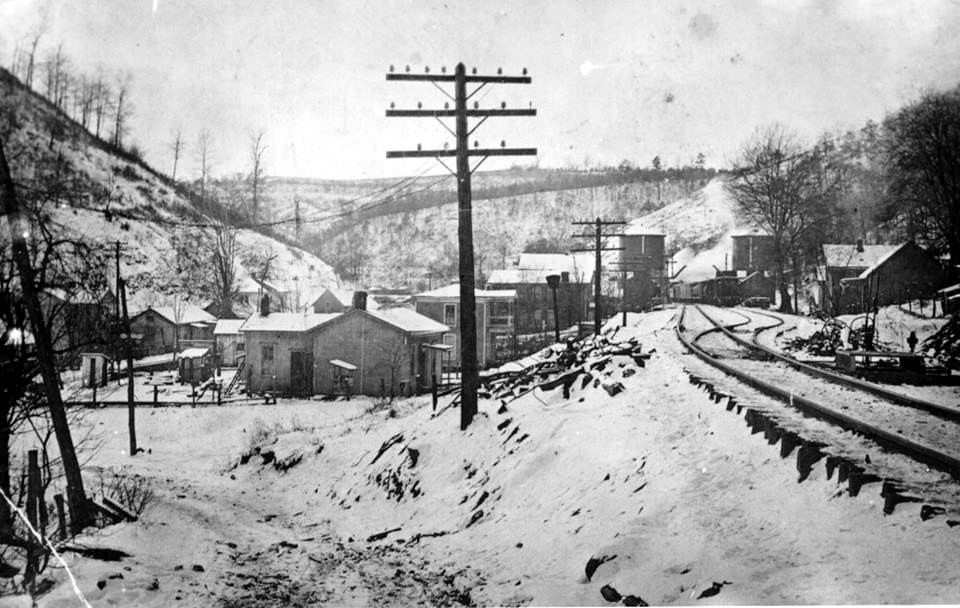

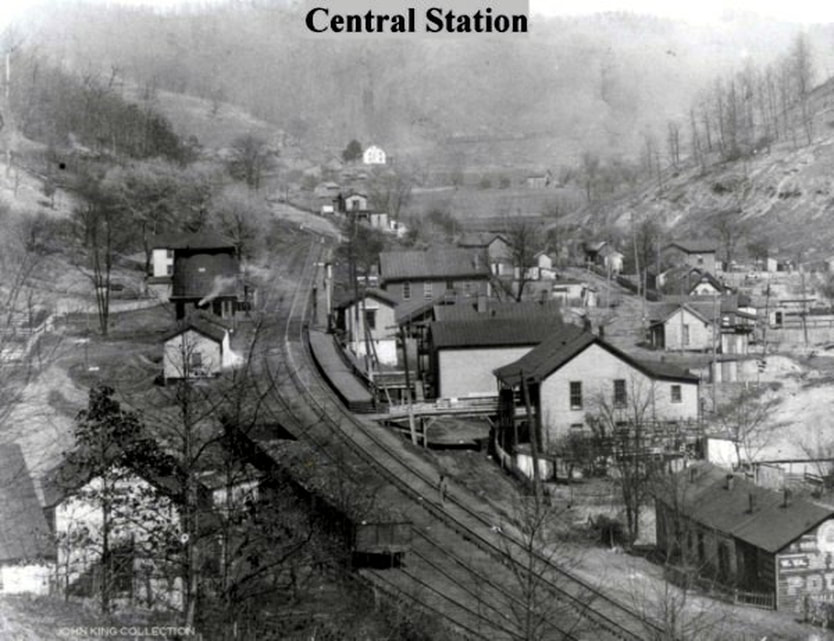

Central Station

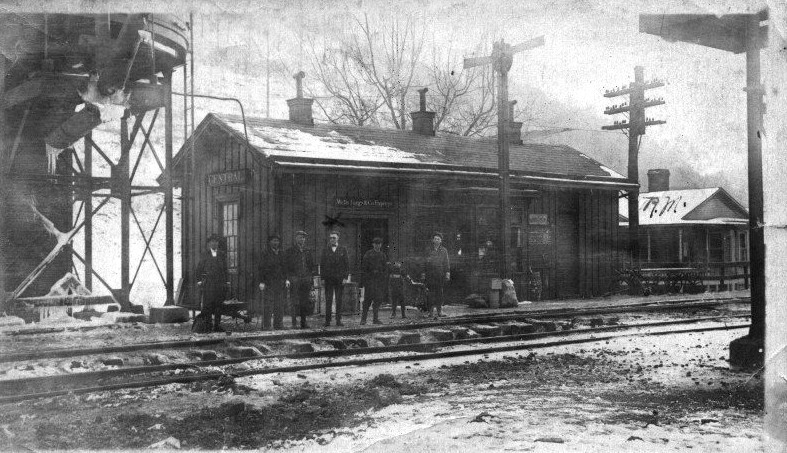

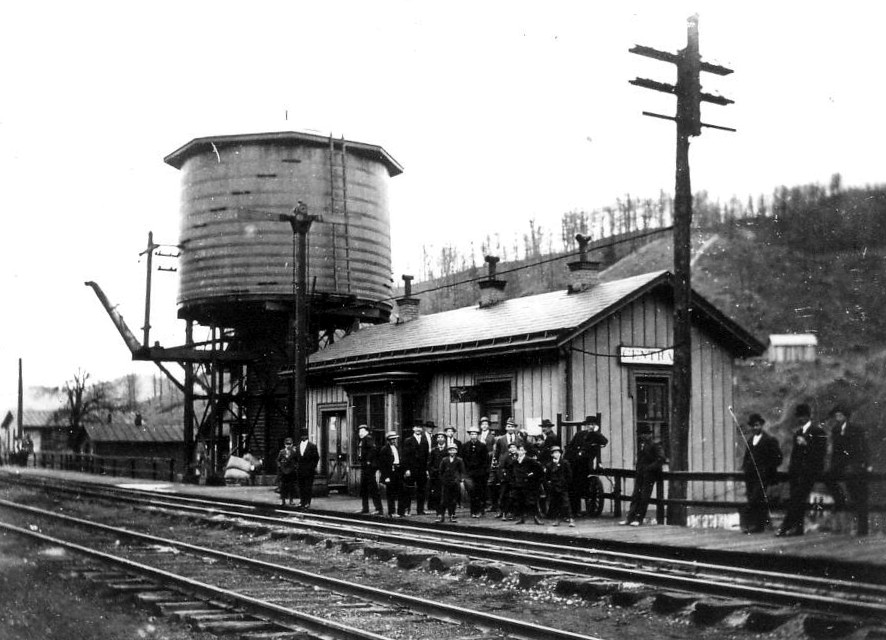

A westbound view of a frigid Central Station in its railroad heyday circa 1910. An atmospheric period image that conveys the town with its association to the B&O. Note the caboose on the westbound train in the siding and the twin water towers. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society.

Central Station was aptly named in regards to its location along the Parkersburg Branch---it was the mid-point of the railroad between Grafton and Parkersburg. It was an important stop during the steam era lasting at least until the World War II years and the site of one the great train robberies in history. For any prospective model railroaders, this community during the steam era would be ideal to replicate on a layout.

|

An early 1900s view of the depot at Central Station. The structure is dark color similar to other B&O depots of the same period. Some of these folks may await a train but most are in the scene posed for the photographer. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society

|

Another early depot image but note the difference of color here. Again a platform filled with people--they are the subject--with railroad structures as a backdrop. The mainline water tower completes the scene. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society.

|

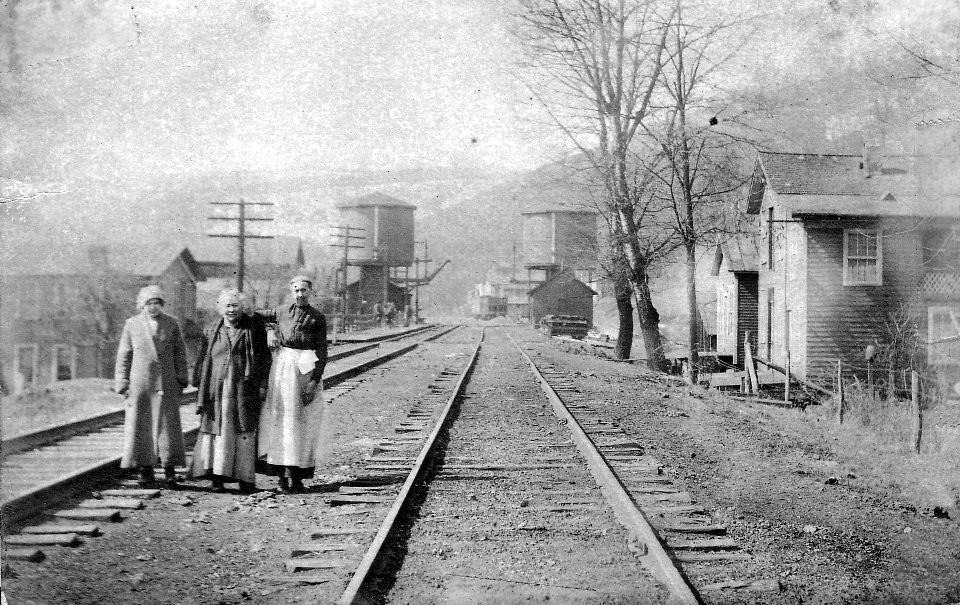

This image has the essence of period photos that appeared in Life Magazine during the early to mid 1900s. The three women are frozen for posterity in a scene that encapsulates the railroad through Central Station during the golden age. A photo from this spot today would provide a stark contrast. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society.

Central Station was an important location for the B&O during the steam era. Equipped with twin water towers, trains stopped here for replenishment of the vital commodity before continuing onward. By the World War II era, the location diminished in significance as B&O no longer listed it as a stop by 1948.

|

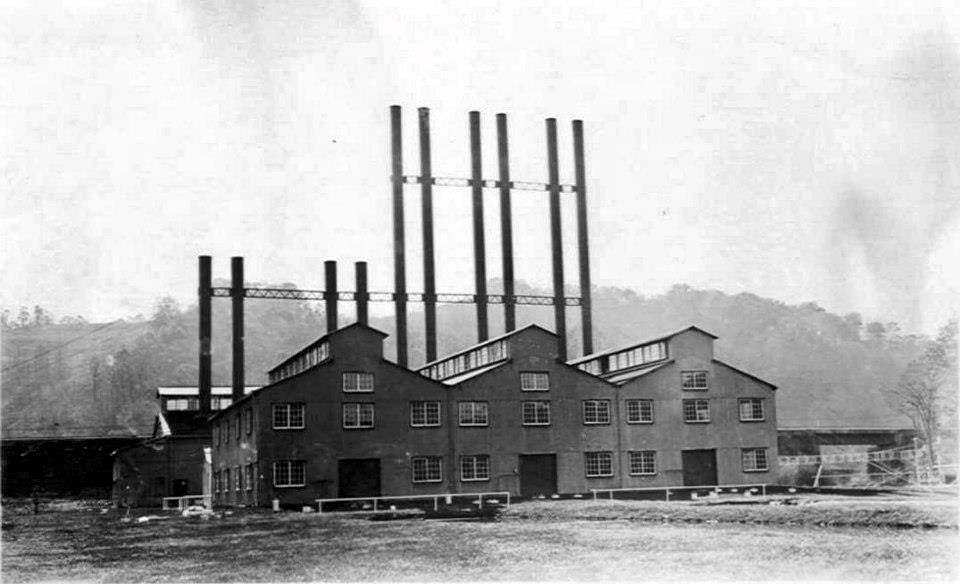

The Equitable Gas Compressor Station located at Central. Not a direct rail shipper but may have had a siding for equipment although not apparent in this view. Unique appearance that would be a great scratch build subject for a model railroad. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society

|

The welded rail on the track dates this image of the Central Station post office to circa 1980. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society

|

A telegraph office was located at Central Station with the call letters CS and there is evidence that a couple of shippers existed here during the early 1900s but were gone by 1950. The passing siding located here was primarily used as a water stop and continued for storage afterward. By 1970, B&O no longer listed Central Station as a siding location.

This circa 1900 view looks eastbound through Central Station. Note there is no mainline water tower but the depot and platform are plainly visible at center. The building at bottom right displays one of the earliest painted iconic Mail Pouch ads. Around the curve and the hill above is the domain of Tunnel #6. Dan Robie/John G. King collection

On the night of October 8, 1915, Central Station entered the realm of train robbery notoriety and in large fashion. At 2AM, two gunmen climbed over the coal in the tender and into the locomotive cab of Train #1 and held the engineer and fireman at gunpoint. They then instructed the engineer to stop the train and ordered the fireman to uncouple the mail car from the remainder of the train. The bandits then ordered the engineer to leave the cab. Three clerks were inside the mail car when the bandits entered demanding the registered mail. Two of the clerks were subsequently ordered from the car and the third clerk remained---as the train was pulled forward a short distance--- in order to show the thieves the location of where additional registered mail was kept. Once the crooks looted the mail, the third clerk was ordered from the car and the train was run west approximately three miles by the bandits to the vicinity of Toll Gate. The thieves made their getaway by an accomplice waiting in automobile and a witness saw the car depart in an easterly direction.

It was determined that the loot taken by the bandits was valued at $500,000 consisting of registered mail and unsigned bank notes. What the thieves did not know was that there was an additional two million dollars in gold left in the express car untouched. Based on testimony from the train engineer on what the bandits said and the fact that they ran the train west of Central Station, it was believed the men had previous railroad experience. They were later apprehended and sentenced to prison.

Train #1, a New York-Cincinnati-St. Louis Limited, frequently carried mail express and valuables that the thieves obviously knew. This high priority first class train was a forerunner of the National Limited that would appear on the timetables in 1925.

It was determined that the loot taken by the bandits was valued at $500,000 consisting of registered mail and unsigned bank notes. What the thieves did not know was that there was an additional two million dollars in gold left in the express car untouched. Based on testimony from the train engineer on what the bandits said and the fact that they ran the train west of Central Station, it was believed the men had previous railroad experience. They were later apprehended and sentenced to prison.

Train #1, a New York-Cincinnati-St. Louis Limited, frequently carried mail express and valuables that the thieves obviously knew. This high priority first class train was a forerunner of the National Limited that would appear on the timetables in 1925.

|

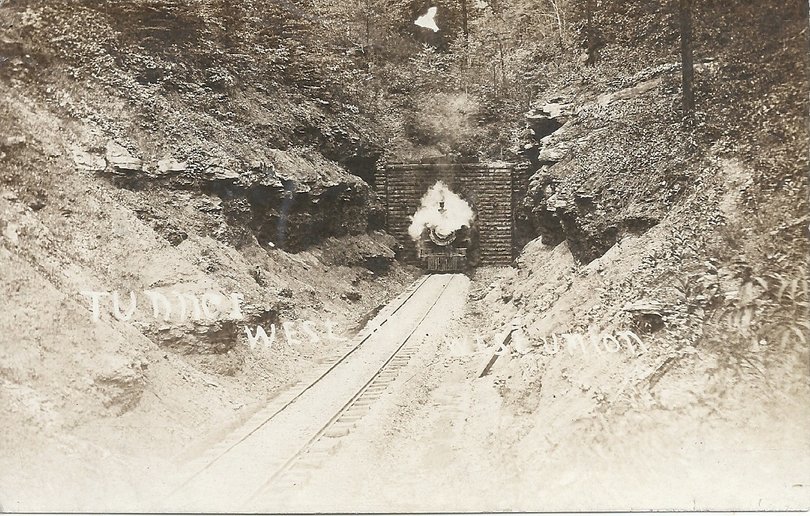

West portal of Tunnel 6. A brick façade at this end with a brick wall built later atop the portal. Date stamped "1969", B&O must have constructed this to prevent slips from landing on track. Note point of light that is the east portal. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

|

Icicles cling to the cut at Tunnel 6 east portal. Stone construction on this end contrasts with wider opening red brick at west end. Point of light is the west portal 2297 feet distant through the bore of this unique tunnel. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation.

|

The rugged terrain in which Tunnel #6 passes. Situated between Central Station and West Union, this bore was certainly a challenge during the 1850s with strictly manual labor. B&O fared well with this tunnel during the 1963 project by lowering the floor and avoiding the potential of the tragic fate that beset Eatons Tunnel to the west.

At 2297 feet in length, Tunnel 6 was the second longest of the twenty three that existed on the Parkersburg Branch--only Tunnel 1 between Clarksburg and Bridgeport exceeded it in length. As with Tunnel 21 at Eaton, this lengthy bore was installed with ventilator fans during the early 1900s to clear smoke and heat as trains passed through it. As trains approached at Central Station or Smithburg, the operator was contacted and would light the boilers which powered the fans. This installation was out of service by the 1930s and for many years afterward, remains could be seen from the fans at Tunnel 6 near the portals.

Left: Fresh air is a moment away for the engineer and fireman emerging from the inferno of heat, smoke and cinders that is Tunnel #6. This fascinating circa 1920 photo is of an unidentifiable train emerging from the east portal and of special note is the smoke that is visible on the hill above the tunnel. Perhaps this is the exhaust fan ventilator in action clearing smoke and heat as this photo corresponds with the era it was in use. Right: Early 1900s view of the main line looking west from near Tunnel #6 west portal. Central Station is to the west beyond the curve. Both images courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

These two images correspond with the two above nearly 50 years later. A trio of GP30s emerge from the west portal of Tunnel #6 with what is likely hotshot freight Gateway 97. The tunnel clearance project has been completed and additional work appears to be in progress with the slip above the portal. Ultimately, B&O would repair the portal and eliminate the slippage problem with the addition of a brick façade. Both of these rare time capsules courtesy of Bill Gordon

In an image circa 1920s, a westbound train heads across the Doe Run bridge with what appears to be a 2-8-0 Consolidation for power. B&O referred to this crossing as Bridge 24 which is located between Tunnel #6 and the town of West Union. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

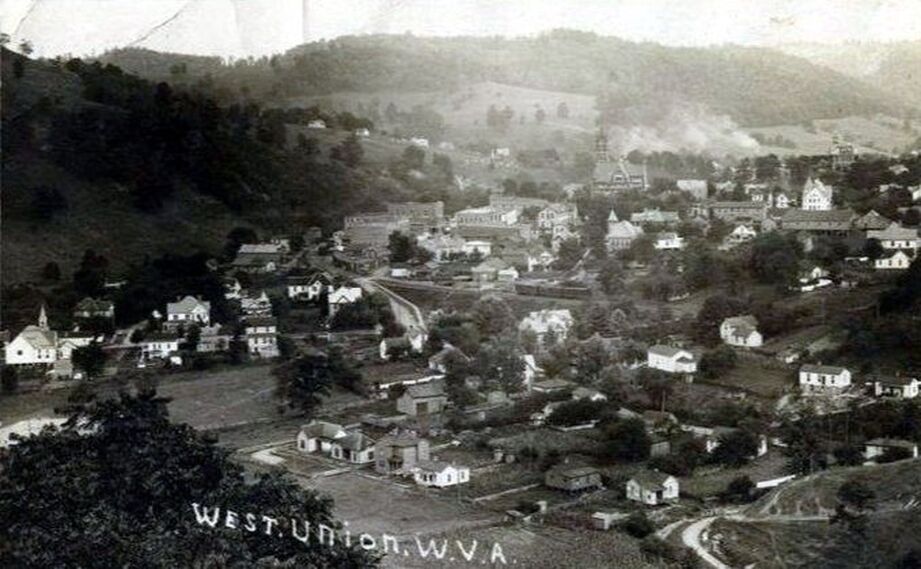

West Union

The history of West Union is quite unique as far as its beginning years. Most towns, once established, eventually enter a period of decline after a period of time and renewal takes place in stages if at all. The county seat of Doddridge County was reclaimed very early after its establishment circa 1845. In March of 1858 as the majority of town residents were in Clarksburg attending a court hearing, fire swept through West Union reducing it to ashes. Though catastrophic, timing for a renaissance could not have better. The building of the Northwestern Virginia Railroad (B&O) was recently completed and its presence helped spearhead an accelerated rebuild of the town.

In a scene that is circa 1950, an eastbound train--possibly a switching local-- is stopped on the main at West Union. The man opposite the locomotive may be the fireman stepped outside the cab. Why the train is stopped was not noted. Could be a problem or another train ahead. One definite is this photo is a wonderful piece of mid 1900s both on the rail and road. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society

The railroad through West Union was essentially a reverse "S" curve. Upon exiting Tunnel 6 eastward, the line curved on an arc through the town then turned east to cross Middle Island Creek on a high deck bridge which also spanned WV Route 18. It then continued on the curve avoiding the sharp turn of the creek by crossing it once again on a girder plate bridge. Since the grade crossings in town were also on a curve, for many years B&O posted a 30MPH speed limit for trains passing through.

|

This image looks eastward freezing West Union as it was in 1910. The B&O main line is visible at town center and there are rail cars on the siding in the vicinity of the depot. A wonderful period photograph that also captures the stately Doddridge County courthouse in its infancy. Image West Virginia & Regional History collection

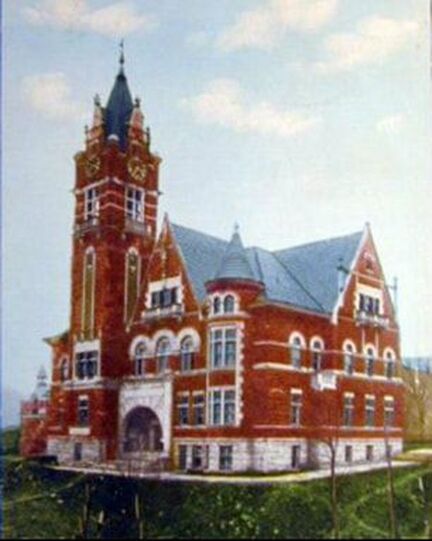

Right:The magnificent Doddridge County Court House at West Union. Surely among the most beautiful not only in West Virginia but the nation as well. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society

|

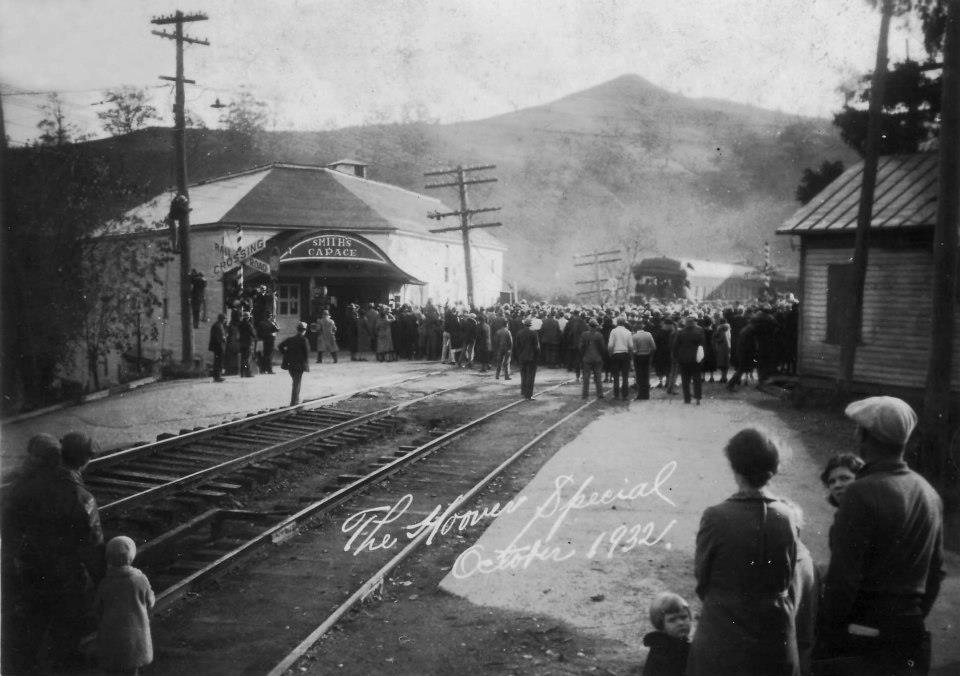

The good people of West Union are gathered to listen as President Herbert Hoover speaks at a 1932 campaign whistle stop. Fate had already dealt its hand---the economic despair and suffering of the Great Depression had soundly doomed his re-election bid. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society

B&O listed no remaining online shippers at West Union by 1948. Considering the industry that was in the area, the fact that all had disappeared by this date is surprising although the siding at the depot was active. An often forgotten aspect of the railroad in the pre-war era was the transport of livestock. Dedicated livestock trains passed through West Union en route to the huge markets at Cincinnati and, if necessary, off loaded here for watering as needed. West Union was one of two communities along the Parkersburg Branch equipped with a livestock ramp.

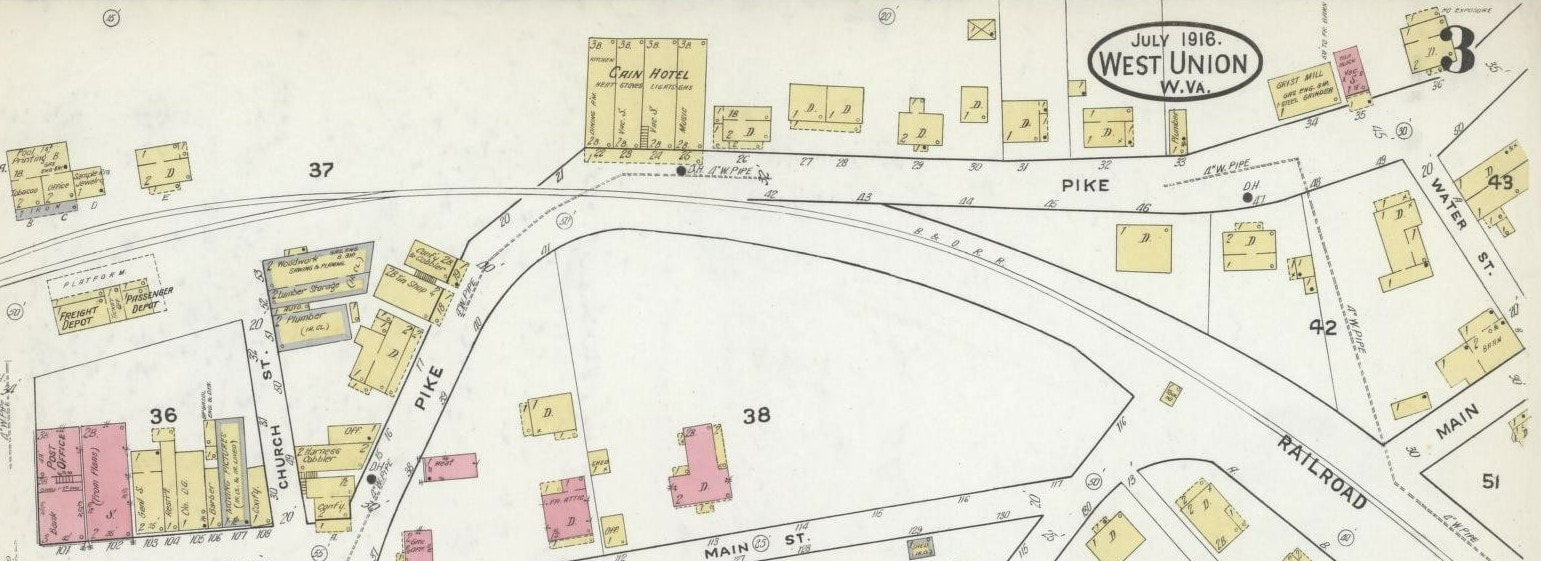

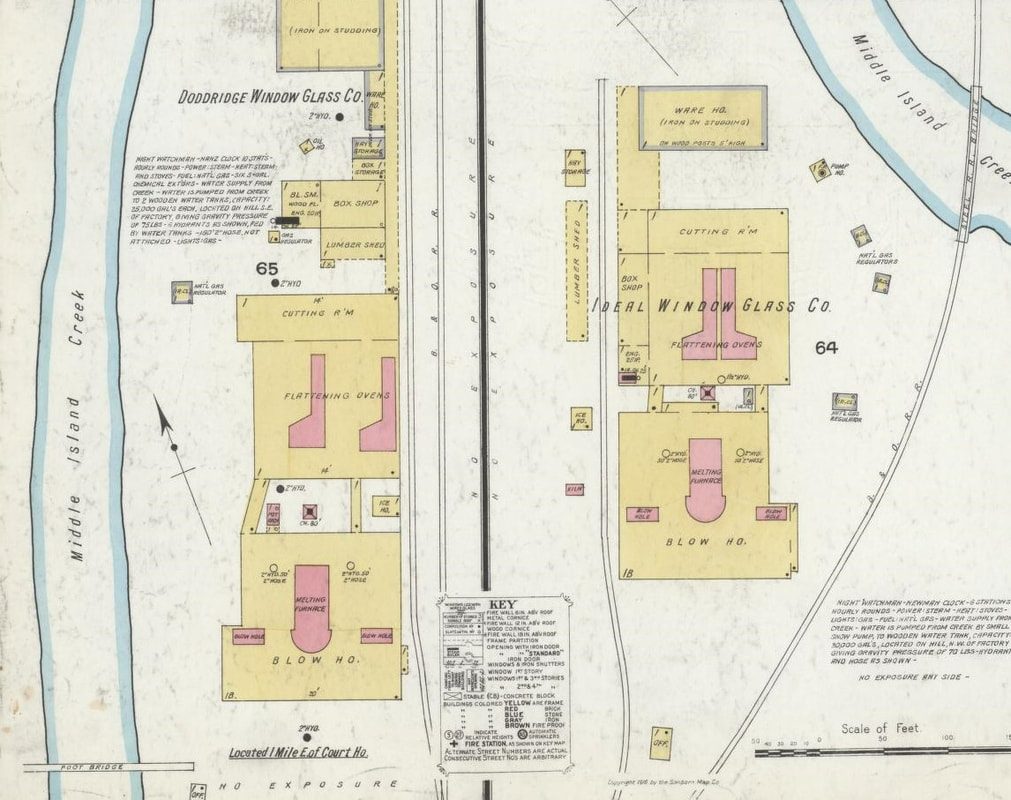

This 1916 Sanborn map offers a view of the east end of the business district. The combination freight/ passenger depot was situated along a passing siding that enabled through traffic to pass on the main.

|

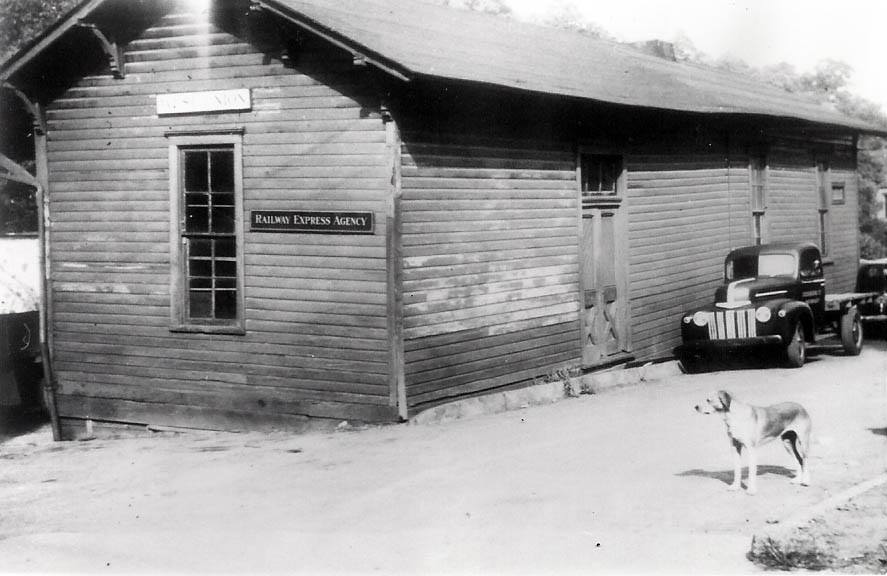

The charms of period photos--West Union depot in happier days, the vintage truck, and yes, our canine friends. A simple life so far removed from the rapid pace of today. We are much the less for it. Image courtesy of Doddridge County Historical Society

|

A westbound view along the B&O main line at the depot. The automobiles stamp the date as being mid 1960s. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society

|

|

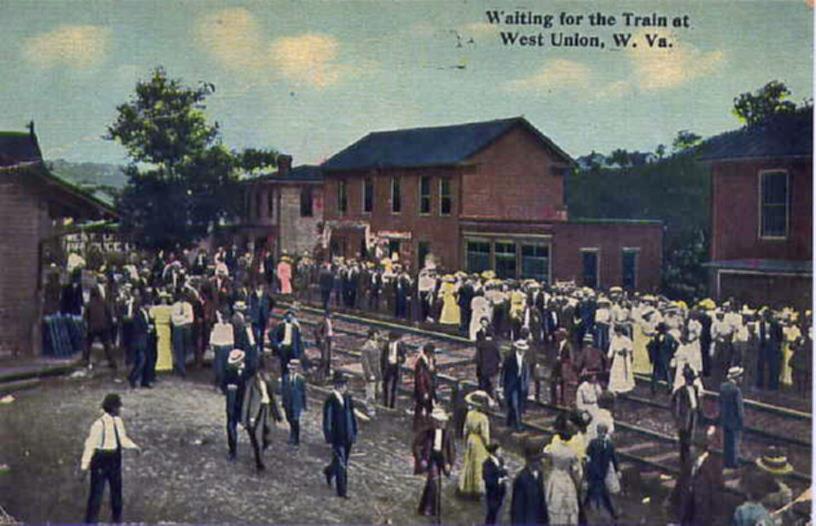

Postcard image made of the West Union depot during the halcyon years of the early 1900s-- perhaps circa 1915. The majority of these passengers awaiting a train are destined to Pennsboro for the Ritchie County Fair. A grand event in a grand era of rail travel. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society

|

Move the clock ahead a half century to train time early 1960s. The large crowds are gone, the depot faded, and the glory years of passenger service a distant memory. But Train #11, the westbound Metropolitan Special, still calls. No passengers in sight this day but the mail service continues. Image Doddridge County Historical Society

|

The west end of the West Union business district in 1916. This map corresponds with the image directly below precisely. Note the locations on both the map and image of the track alignment, the stock pen, and even the concrete phone booth. As with the depots, the passing siding allowed livestock trains to stop for watering without fouling the main line.

An interesting view at West Union circa 1920s. Of particular note is the livestock ramp at right used to unload cattle for watering before continuing westward. The concrete phone shack at left was a common design used throughout the B&O system for crews to contact dispatchers. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society

West Union was a primary passenger stop along the B&O Parkersburg Branch and its status as a seat of county government further reinforced it. The secondary passenger trains stopped here but as their numbers dwindled so did the number of stops. West Union remained on the timetable as a flag stop for the Metropolitan Special until B&O ceased passenger operations on April 30, 1971. It was omitted as a passenger stop for Amtrak trains during the 1970s and 1980s.

A 1930s derailment at the east end of town in a view looking westbound where Railroad Street parallels the track. The eastbound West Union signal (CPL) is at left and the finely manicured ballast is indicative of a well-maintained right of way. Derailment likely occurred from an axle journal (hotbox) failure on a freight car. Image Doddridge County Historical Society

|

A picturesque image of the railroad bridge spanning Middle Island Creek and WV Route 18. B&O listed this deck truss bridge as Number 23 on the Parkersburg Branch. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society

|

A 1979 view of the railroad east of the Middle Island Creek high bridge. Image courtesy Kathryn Basset/Town of West Union

|

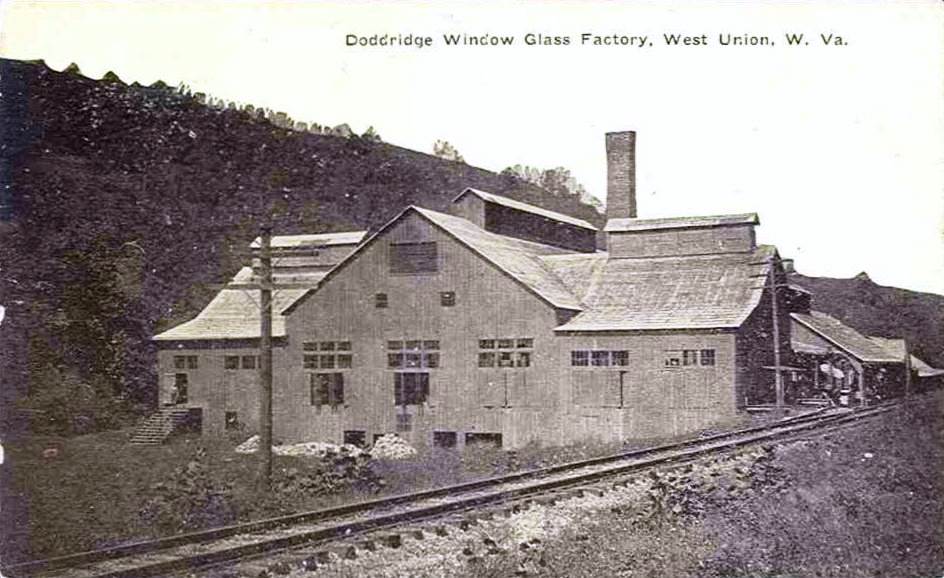

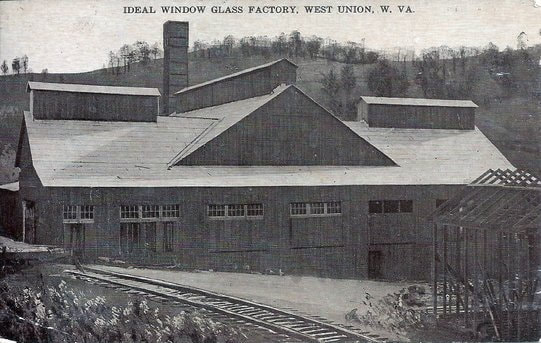

The glass industry located at West Union during the early 20th century was significant. Two such shippers along the B&O were the Doddridge Window Glass Company and the Ideal Window Glass Company. These two industries also employed a respectable number of employees during their prime.

|

The glass industry had a large presence in the West Union area though most was gone by World War II. Doddridge Window Glass Company was one such business. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society

|

The Ideal Window Glass Company located along the railroad at the east end of town. Plant was near the second crossing of Middle Island Creek. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society

|

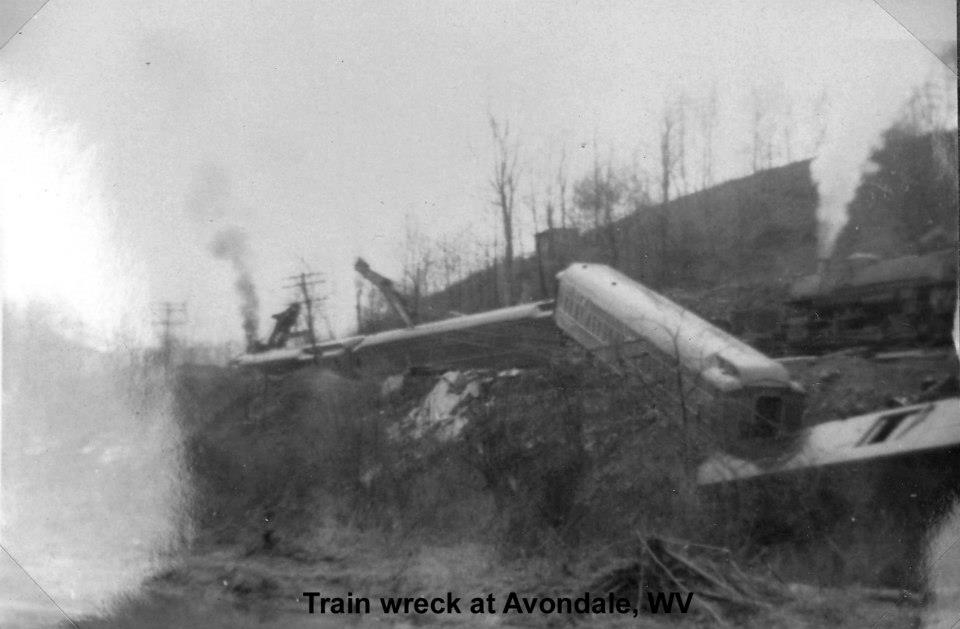

The region between West Union and Smithburg has long been an

area known as Avondale. The railroad directly parallels Middle Island Creek

through here on a series of cuts and fills. Operationally, the only

significance of the section was the water station at Rock Run but it was the scene of a tragic derailment that occurred

in 1953.

On April 17, 1953, westbound passenger Extra 5049 lead by P1 Pacific #5049 and ten cars consisting of sleeping cars, baggage car, and kitchen car, passed Smithburg at 6:31 PM taking the green proceed signal as indicated. Moving at 35 MPH, the train passed through Tunnel 5 and across Bridge 21 (Middle Island Creek) to a point approximately 3/4 mile west of the Smithburg depot. At this point, the locomotive was on a gradual curve at a private grade crossing when the drive wheels and trailing truck left the track to the north precipitating the derailment.

On April 17, 1953, westbound passenger Extra 5049 lead by P1 Pacific #5049 and ten cars consisting of sleeping cars, baggage car, and kitchen car, passed Smithburg at 6:31 PM taking the green proceed signal as indicated. Moving at 35 MPH, the train passed through Tunnel 5 and across Bridge 21 (Middle Island Creek) to a point approximately 3/4 mile west of the Smithburg depot. At this point, the locomotive was on a gradual curve at a private grade crossing when the drive wheels and trailing truck left the track to the north precipitating the derailment.

|

P1 Pacific #5049 lays on its right side with the tender buckled behind it. The track is obscured by the smoke and places into context the distance the locomotive came to rest. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society.

|

The remainder of the train with cars in different dispositions. Two "big hooks"--cranes--work the derailment site rerailing cars and lifting equipment on the ground. View is to the east. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society.

|

Linear momentum of the locomotive in the curve caused it to leave the track and turnover on its right side coming to a stop 530 feet west of the derailment point and 15 feet north of the track. The locomotive tender remained attached and came to rest with its front end against the rear of the locomotive at a 75 degree angle. The first car in the consist was separated from both the tender and second car and overturned on its right side parallel to the track. Cars two through ten were derailed but remained upright sustaining damage of varying degrees.

The engineer was killed and the fireman was seriously injured. There were no reported injuries among the passengers and other railroad personnel. Extra #5049 was a westbound troop train during the era of the Korean War. Reports indicated the locomotive was in good order and the track had been inspected for cracks in this area three days prior to the accident. The ICC concluded the derailment was caused by an overturned rail.

The engineer was killed and the fireman was seriously injured. There were no reported injuries among the passengers and other railroad personnel. Extra #5049 was a westbound troop train during the era of the Korean War. Reports indicated the locomotive was in good order and the track had been inspected for cracks in this area three days prior to the accident. The ICC concluded the derailment was caused by an overturned rail.

A 2003 Google Earth view of the west end of Smithburg that includes Avondale. The 1919 and 1953 derailment points are indicated above and occurred within a mile of one another. Key locations such as Tunnel 5--a cut since 1963-- and Bridge 21 across Middle Island Creek occupy the area between both accidents.

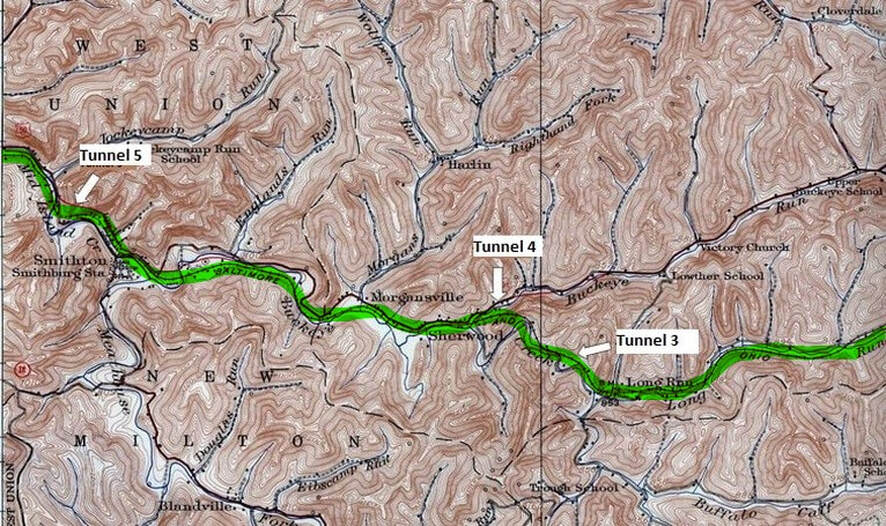

Smithburg to Long Run

The B&O continued along Middle Island Creek and passed through Tunnel 5 before emerging at Smthburg. At this location, the line then followed Buckeye Run to Sherwood and crossed over to the Long Run drainage through Tunnel 4. The railroad continued along this basin eastward passing through the short Tunnel 3 to avoid a sharp bend in the stream.

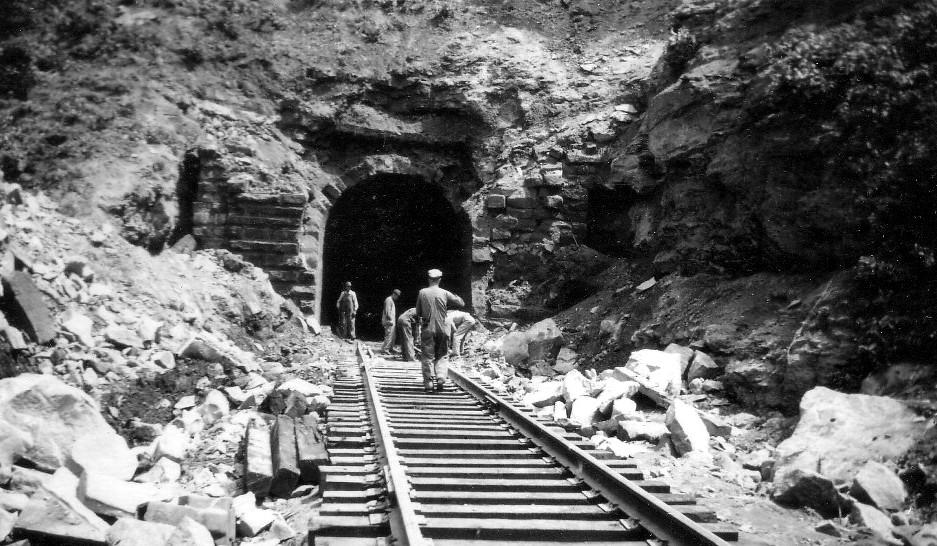

Before the railroad reached Smithburg, it passed through the 359 foot Tunnel 5--also known as Shannon Tunnel-- to bypass a sharp bend in Middle Island Creek. During the 1963 tunnel clearance project, B&O engineers determined that Tunnel 5 was not suitable for bore enlargement and due to its relatively short length was subsequently daylighted.

There was no identification on this image but it may be of Tunnel 5 and the work in progress to daylight it. The portal façade is crumbled and the rock at trackside indicates work is occurring above. Tunnel 5 is the only one that was daylighted in Doddridge County during the 1963 project. Located just west of Smithburg, it would have been easily accessible for the photographer. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society.

Smithburg

The stillness of the Smithburg morning was shattered on September 26, 1919 at 10:10 AM when a second section of Train 97, a Grafton-Parkersburg freight, passed the station and tragically derailed at the west end of town near Tunnel 5. No previous concerns had been reported at Smithburg prior to the accident.

Train 97 was moving at approximately 30 MPH as it passed through town with thirty-two cars and caboose as it approached the switch at the west end of the Smithburg passing siding. The locomotive, #4059, a Class 2-8-2 Q1a Mikado, derailed at the switch point on a five-degree curve but continued to follow the contour of the track on a short tangent before curving right in a cut to the east portal of Tunnel 5. After running derailed for over 400 feet, the locomotive came to rest just inside the east portal of the tunnel but sustained no damage. It was determined that it had partially remained on the track to the point of the tunnel with the tender remaining attached and also coming to rest against the tunnel portal. The tender trucks were detached coming to rest behind it to the east approximately 20 feet. In series, the first three cars remained coupled leaned against the left side of the cut with the fourth car having telescoped the third. Cars four through six were across the track and the next eleven piled in a mass. The track switch at the west end was torn out along with 400 feet of track to the tunnel entrance. The engineer was killed and the fireman sustained serious injury. Ironically, the engineer was on his first run since returning from a ten-day vacation.

During the trip preceding the derailment, crew members reported that the locomotive tender was not riding correctly with an up and down motion. Problems had been reported with this tender earlier in the month at Grafton but no defects were found. Investigation on this accident attributed both a wheel problem on the tender and track conditions at the west end passing track switch to the cause of the derailment.

Train 97 was moving at approximately 30 MPH as it passed through town with thirty-two cars and caboose as it approached the switch at the west end of the Smithburg passing siding. The locomotive, #4059, a Class 2-8-2 Q1a Mikado, derailed at the switch point on a five-degree curve but continued to follow the contour of the track on a short tangent before curving right in a cut to the east portal of Tunnel 5. After running derailed for over 400 feet, the locomotive came to rest just inside the east portal of the tunnel but sustained no damage. It was determined that it had partially remained on the track to the point of the tunnel with the tender remaining attached and also coming to rest against the tunnel portal. The tender trucks were detached coming to rest behind it to the east approximately 20 feet. In series, the first three cars remained coupled leaned against the left side of the cut with the fourth car having telescoped the third. Cars four through six were across the track and the next eleven piled in a mass. The track switch at the west end was torn out along with 400 feet of track to the tunnel entrance. The engineer was killed and the fireman sustained serious injury. Ironically, the engineer was on his first run since returning from a ten-day vacation.

During the trip preceding the derailment, crew members reported that the locomotive tender was not riding correctly with an up and down motion. Problems had been reported with this tender earlier in the month at Grafton but no defects were found. Investigation on this accident attributed both a wheel problem on the tender and track conditions at the west end passing track switch to the cause of the derailment.

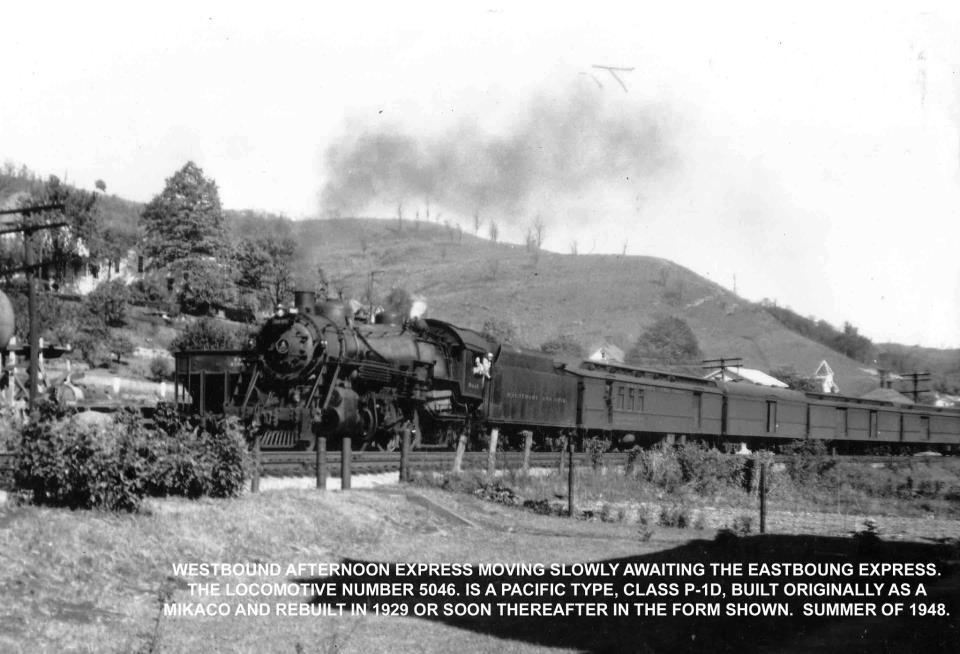

A fine period image of Train #11, the Metropolitan Special, awaiting a meet with its eastbound counterpart, Train #12 at Smithburg. These trains were heavy with mail and express and the stout P1d class Pacifics were common power to pull them. The year 1948 would be an excellent selection on a time machine to visit the Parkersburg Branch. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society.

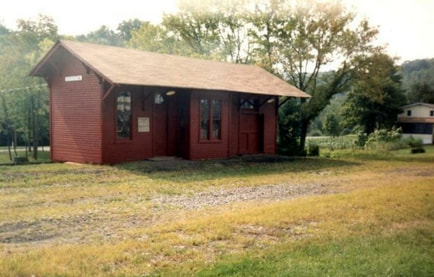

To a curious observer visiting the depot at Smithburg, confusion may result from the name of the structure posted as “Smithton”. The town was founded as Smithburg but to alleviate conflict with another depot on its system, B&O opted for the name of Smithton here. Hence, at Smithburg, West Virginia, two different names for the same place location. Until the 1951 implementation of CTC, Smithburg was a block station with B&O call letters SN. The sidings here were lapped and an operator, agent, and clerk were on duty around the clock.

The B&O main line with a passing siding and storage track still intact at Smithburg in 1978. Although the forlorn looking depot would receive a new lease on life several years later the same could not be said for the railroad. Image Karl Underwood/Todd M. Atkinson collection

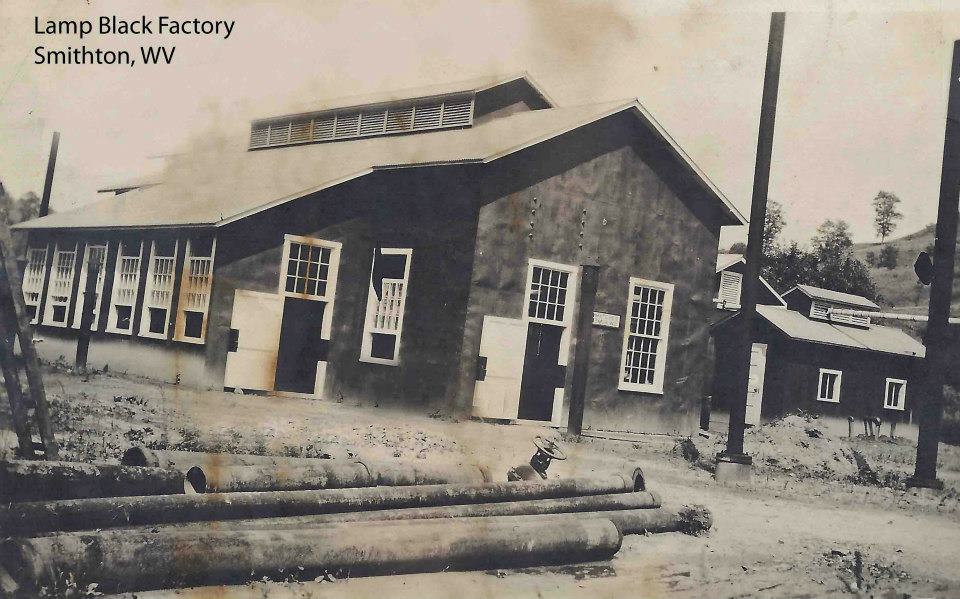

Smithburg is located in what once was the great oil and glass industry belt but it was also home to lamp black plants. This material was produced by the incomplete combustion of heavy oils and the compounds were used as pigments and additives to explosives, fertilizers, and lubricants. This industry vanished from the scene at Smithburg as a rail shipper for B&O---in fact, the company listed no remaining shippers at all by the post- World War II era.

The Metropolitan Specials meet at Smithburg circa 1948. Westbound #11 is going away and eastbound #12 faced the photographer. Smithburg was a common meeting point for these trains during this era. Image Dan Robie/John G. King collection

|

A big business in Smithburg was the lamp black industry. Producing fine carbon based powder, its uses were many. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society

|

This was the sad sight along the Parkersburg Branch during 1988. Rail removal train at Smithburg. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society

|

The year 1950 was devastating for the communities within the

region and B&O due to a severe flash flood. Virtually every town was affected along the

B&O from Ritchie County to Clarksburg but Smithburg was hit especially

hard. Middle Island Creek left its banks and washed homes downstream of which

a number were stopped by the railroad bridges between Smithburg and West Union. In

its wake the flooding within several counties of north central West Virginia

cost thirty-three lives and rampant property damage.

|

Capsules in time never to be seen again. The young boy is now telling his grandchildren about riding Amtrak over the Parkersburg Branch in 1973. Both he and the conductor of the Potomac Special await the arrival of a westbound at the east end of the Smithburg siding. Bridge #20 crossing Buckeye Creek is just beyond the switch. Image courtesy Ken Adams collection

|

The meet….B&O GP40-2 #4113, among the first group of locomotives delivered after the formation of the Chessie System, lead what is possibly Gateway 97 or the St. Louis Trailer Train past Amtrak waiting in the hole. In the distance is recently completed US 50 four lane highway. Image courtesy Ken Adams collection

|

Sherwood

A period photo of the small community of Sherwood perhaps circa 1940s. This area adjacent to the railroad disappeared from the Corridor D US Route 50 project during the early 1970s. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

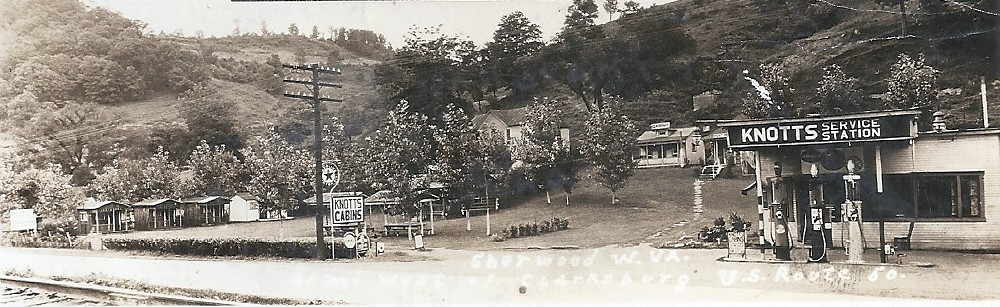

As the railroad moved eastward from Smithburg, it passed through the small communities of Morgansville and Sherwood. Neither was of commercial importance to B&O----if any shippers existed here early in the history of the line, they had long since vanished from the scene. Sherwood is best known as the location of the 846 foot long Tunnel 4 which also bears the same name.

A 1997 Google Earth image of the area between Long Run and Sherwood that encompasses Tunnels 3 and 4. The original bore of Trough Tunnel (#3) is visible adjacent to the cut that bypassed it. The railroad entered the east portal of Sherwood Tunnel (#4) on a curve and emerged from the west portal at the community that bears the same name along US Route 50.

GP40-2 #6198 and mate exit the east portal of Tunnel 4 at Sherwood. The number reveals that it is a CSXT locomotive now although still in Chessie System paint. The occasion is a sad one----it is August 1988 and the Parkersburg Branch track removal continues eastward. At this point, the railroad is gone from Walker to Smithburg. Image courtesy Alan Nichols/Doddridge County Historical Society.

Between Tunnel 4 and Long Run is the location of Tunnel 3 also known as Trough Tunnel. This 282 foot bore was bypassed during the 1963 clearance project with a cut.

|

The west portal of Tunnel 3 at Long Run, one of three bypassed with a cut in 1963. Rock instability accounts for the retaining wall on the north side of façade. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

|

Concrete remains from another time. Remnants of the block station located at Long Run. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

|

Long Run

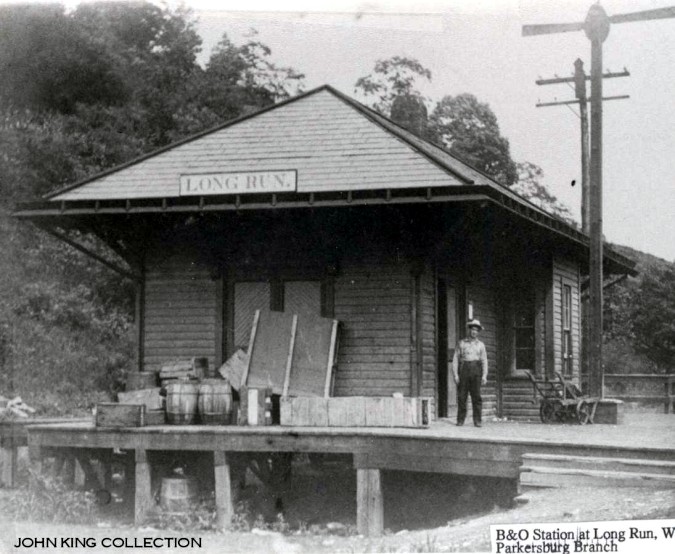

Long Run was the location of a depot and a telegraph office with B&O call letters DA. A block station was located here to operate the single conventional siding in the days before CTC. During the postwar era, the Long Run siding was eliminated for meets and was no longer listed in the timetable by 1963.

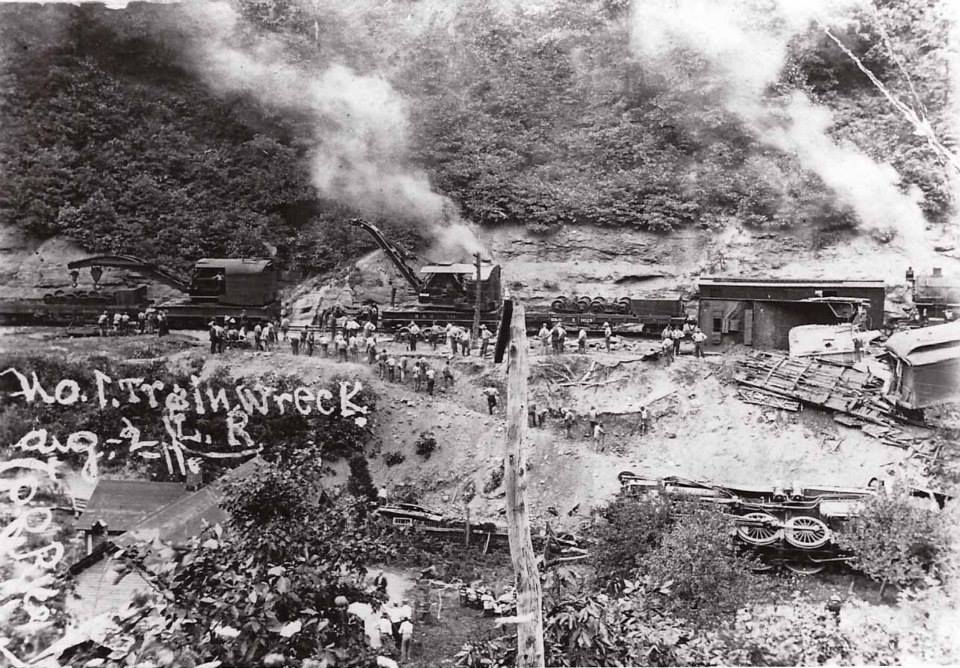

The aftermath of an August 2, 1911 accident at Long Run. Train #1--the westbound New York-Cincinnati-St. Louis Express--derailed with the loss of two lives. Heavy cranes have been dispatched from Grafton on a relief train to clean up the mess and restore the main line to service. Image Doddridge County Historical Society

|

The depot at Long Run as it appeared circa 1920. View is at the west end. Dan Robie/John G. King collection

|

Another view of the Long Run depot from its east side. Also circa 1920s. Image courtesy Doddridge County Historical Society.

|

Long Run to Bristol

B&O continued its eastbound ascent paralleling Long Run reaching the community of Industrial. Crossing from Doddridge to Harrison County, the railroad passed through Salem running adjacent to Salem Fork until the community of Bristol. Tunnel 2, eastern most of the now abandoned bores, is located east of here.

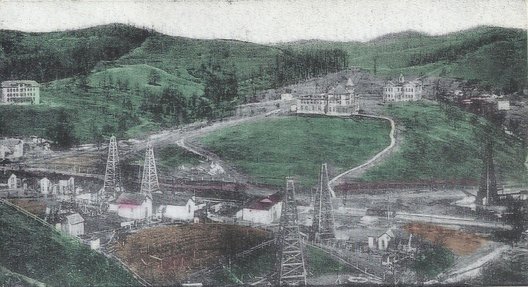

Industrial

Moving east from Long Run and paralleling the creek by the

same name, the railroad climbed east adjacent to the creek ridge until reaching

the community of Industrial. Straddling the Doddridge-Harrison County line, the

community was of commercial importance to B&O during the early 1900s. This

region, just as the area the railroad traversed in Ritchie County, was situated

on a booming oil field that created growth in the region and carloads for

B&O.

In spite of the road grime, B&O GP38 #3830 was a new to the roster when this 1968 photo was taken at Industrial. The train is probably Cincinnati 97 running westbound with an F7B sandwiched between the GPs. This rare photo location also offers a glimpse of the Girls Home on the hill. Image courtesy Donald Haskel

At this point I wish to acknowledge Donald Haskel for the image above and the ones to follow. Photographs of the Parkersburg Branch during the 1960s and later are scarce and it is a privilege to include his efforts to share with others.

|

Artist rendition of Industrial during the great oil boom of the early 1900s. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

|

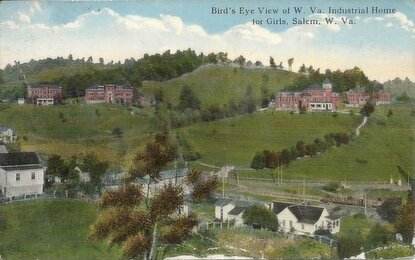

Postcard image taken after the boom perhaps circa 1920s. Although the Girls Home is the subject, it includes a view of the railroad below. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

|

By 1968, this is what remained of the National Limited. An E8 and single coach move eastbound through Industrial with a train renamed The West Virginian. A flag stop lay ahead at Salem--- if needed. Image courtesy Donald Haskel

Salem

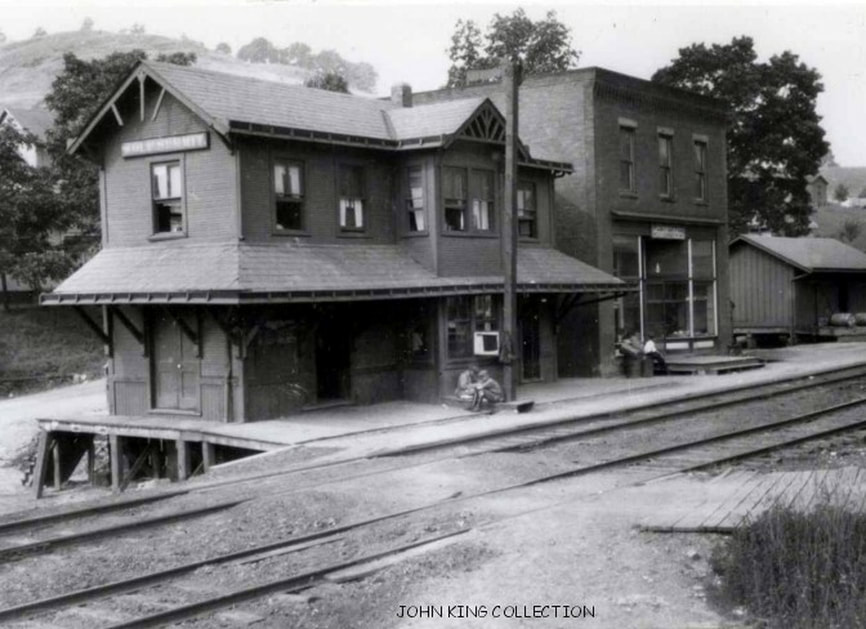

A rare image of the wood Salem depot circa 1900. Customary for the era, photographers posed people with shots of locomotives and depots. This must have been a special occasion now lost to time--perhaps a special train on the way with dignitaries or a large group of people traveling to an event such as the Pennsboro Fair. Image B&O Magazine Archives

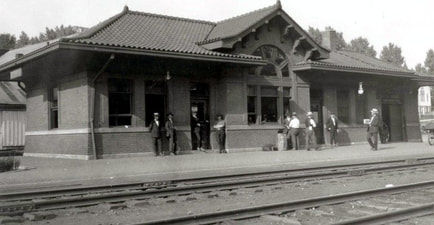

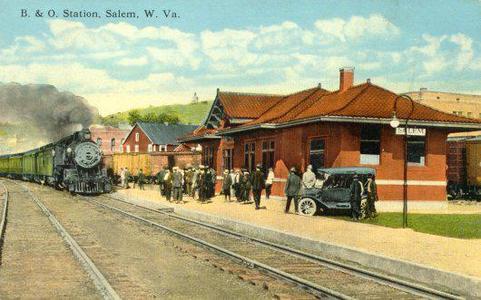

Circa 1920 postcard of train time at Salem. A wonderful print of the beautiful brick depot in its prime seasoned with period flavor. Passengers wait to board the eastbound train. Image courtesy Blackwood Associates

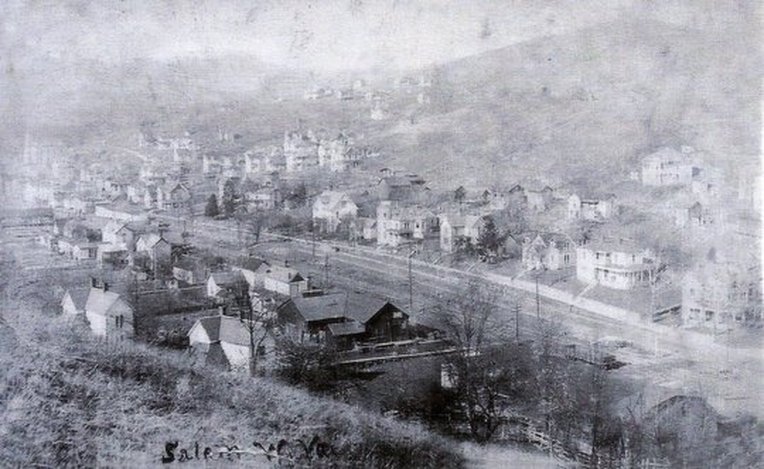

The B&O entered Harrison County into the town of Salem which was a significant location along the railroad. During the mid-1800s and lasting until the late in the century, the Harrison County region was a large producer of beef cattle. The livestock would be moved to Salem and loaded on railcars destined for market. Oil dominated its early 1900s industrial history and later the development of glass manufacturing played a prominent role in its commercial development.

The B&O entered Harrison County into the town of Salem which was a significant location along the railroad. During the mid-1800s and lasting until the late in the century, the Harrison County region was a large producer of beef cattle. The livestock would be moved to Salem and loaded on railcars destined for market. Oil dominated its early 1900s industrial history and later the development of glass manufacturing played a prominent role in its commercial development.

As population and industry increased, the stature of Salem as a passenger stop increased. But for the exception of premier trains such as the National Limited and Diplomat, virtually all other trains stopped here. Salem remained as a stop on the schedule for the Metropolitan Special until B&O passenger service ceased on April 30, 1971. It was not included in the Amtrak timetable in subsequent years.

Although it was nearly a decade since the last passenger train stopped at Salem, the building still retains a dignified appearance in this 1978 photo. One could still park at the Salem station at this date and watch the trains pass or perhaps see one take the siding here--the longest one between Parkersburg and Clarksburg. Image Karl Underwood/Todd M. Atkinson collection

The 1912 depot at Salem was the epitome of all such structures along the Parkersburg Branch with its brick construction and architecture. When passenger service ceased in 1971, the building lay dormant but was restored as a centerpiece for the town and the North Bend Rail Trail after the railroad was removed in 1988. Tragically, the structured was gutted by fire in 2008 and to date the restoration is not yet complete.

Fire has been synonymous with Salem. The great fire of 1901 devastated the business district and another in the post rail era of 2006 affected the same area. The town has also been victimized by flooding with the most notable being the devastating flash flood of 1950 that inflicted substantial damage.

Fire has been synonymous with Salem. The great fire of 1901 devastated the business district and another in the post rail era of 2006 affected the same area. The town has also been victimized by flooding with the most notable being the devastating flash flood of 1950 that inflicted substantial damage.

|

A very old and rare image of Salem that appears to predate the oil boom of the early 1900s. The B&O splits the town and especially noteworthy in this scene are the sizes of the homes scattered through the community. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation.

|

One of many floods that have afflicted Salem throughout its history. This 1905 scene in the business district has totally submerged the railroad. Image West Virginia and Regional History

|

|

The booming glass industry at Salem generated carloads of business for B&O. Image depicts early 1900s heyday. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

|

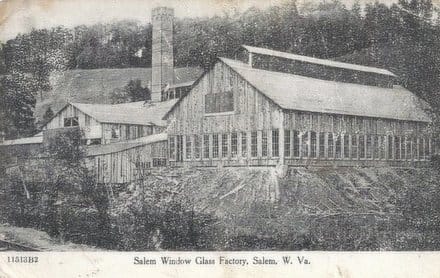

The Salem Window Glass Company was one of several firms in business during the peak of glass manufacturing. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

|

The print is damaged but is a clear indication that the railroad through Salem is on short time. It is September 1988 and a rail train moves eastbound as the track removal continues to the west. Not much farther to go now to reach Wolf Summit which would be end point of the removal at the east end. Image courtesy of Anne Mish

Salem was a block station with B&O call letters SA and the location of the longest passing siding between Parkersburg and Clarksburg. Records indicate it was originally a lapped siding but was converted to a conventional siding exceeding 5000 feet in length. A coaling station and livestock watering facility were also located here during the steam era. B&O listed two online shippers still active at Salem by 1948---Bowser Sales and the Truman Riley Lumber Company. The great oil and glass industry had evaporated by World War II in regards to the railroad.

These men now peer through two different centuries at us as they pause on their handcar for the photographer. This photo dates from the late 1800s along the main line near Bristol. Image courtesy Harrison County Historical Society

|

The east portal of Brandy Gap or Tunnel 2. To the right side is the telltale drain pipe that will quickly identify as an image of this tunnel. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation.

|

Parkersburg Branch tunnels are low by modern railroad standards but are taller than they may imply. This portal shot places into context how high the clearance truly is. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

|

The B&O paralleled Salem Run east of town to the community of Bristol. Hope Natural Gas was listed as shipper in 1948 and the town remained on the timetable as a flag passenger stop until the late 1950s for Trains #23 and #30, the West Virginian.

The 1086 foot long Tunnel #2 is located east of Bristol and is known as Brandy Gap or Flinderation Tunnel. Legends abound about this bore as a haunt from years ago when a train purportedly struck workers inside the tunnel. Like its counterpart of lore at the west end of the Parkersburg Branch, Silver Run, it is a magnet for the curious.

The 1086 foot long Tunnel #2 is located east of Bristol and is known as Brandy Gap or Flinderation Tunnel. Legends abound about this bore as a haunt from years ago when a train purportedly struck workers inside the tunnel. Like its counterpart of lore at the west end of the Parkersburg Branch, Silver Run, it is a magnet for the curious.

Wolf Summit to Adamston

Continuing the eastbound climb through Maken, the B&O reached the high point of the Parkersburg Branch at Wolf Summit. The railroad then descended along the Limestone Run drainage passing through Reynoldsville and Wilsonburg before reaching the outskirts of Clarksburg at Adamston.

The region at Wolf Summit began a pocket of industrialization that extended into Clarksburg dominated by the coal mining industry. Ironically, in a sector of the state where coal was predominant, the area west of Clarksburg was the only such sector adjacent to the Parkersburg Branch. Moving eastward, the towns of Wolf Summit, Reynoldsville, Wilsonburg, and Adamston were populated with mining activity during their respective histories.

Wolf Summit

Circa 1905 image looking east through the community of Wolf Summit. Early development of the mining here is in evidence on the hillside opposite (left) of the railroad. The Parkersburg Branch--and the B&O mainline---attained its highest elevation above sea level here between Grafton and St. Louis. Image West Virginia and Regional History.

As the highest point on the Parkersburg Branch, Wolf Summit is appropriately if not colorfully named. It may come as a surprise that this location (1119 feet) is higher in elevation than Grafton (1024 feet), gateway to the mountainous railroad east over the Alleghenies. In terms of the St. Louis main line, it was also the highest elevation point on the railroad between Grafton and St. Louis.

The depot at Wolf Summit as it appeared during the 1920s. A unique two story design with a platform trackside and wrapping around the rear. A smaller freight depot is also visible in the scene and the brick building at the center still stands today. Dan Robie/John G. King collection

This is a classic scene of Train #11, the Metropolitan Special, passing westbound through Wolf Summit in 1967 for the symbolism alone. A mail bag awaits on the hook to be taken by the train on the move led by E8 #1441 but this time honored practice would soon end. Mail transport would cease on the Metropolitan Special that year as the postal service removed it from the railroads. An outstanding image of a bygone era courtesy of Donald Haskel

Wolf Summit 1967... |

...Wolf Summit 2014 |

|

A westbound manifest, perhaps Gateway 97, takes the siding at Wolf Summit for a meet. The solid F7 lashup power led by #4552 was becoming a rarity by this date. A fairly good look at the east end CPL at Wolf Summit in another exceptional photo by Mr. Haskel. Image courtesy Donald Haskel

|

What a difference a half century makes. This is nearly the same vantage point as the 1967 photo at left and only the house with the covered porch is common to both. The brick building is the same one pictured in the 1920 photo above and the gate in the distance marks the 1988 east sever point of the Parkersburg Branch. Image courtesy North Bend Rail Trail Foundation

|

Wolf Summit was an important location on the Parkersburg Branch in terms of operations. Lapped passing sidings were located here in addition to a depot, an agent, and block operator. Assigned B&O call letters WS, it was after the onset of CTC the first location for meets west of Clarksburg. As of 1948, B&O listed the Gregory Mine Number 3 and Hilltop Mine Number 2 as shippers with the Gregory Mine generating carloads of coal for B&O until circa 1980. Coal operators that operated mines here during the early 1900s include the Alpha Portland Cement Company (Phoenix Mine), Hudson Coal Company, Hutchinson Coal Company, and the Wolf Summit Coal Company.

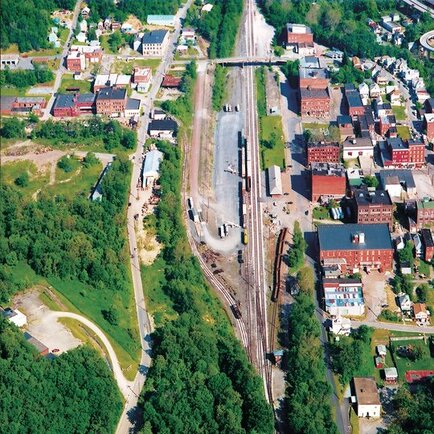

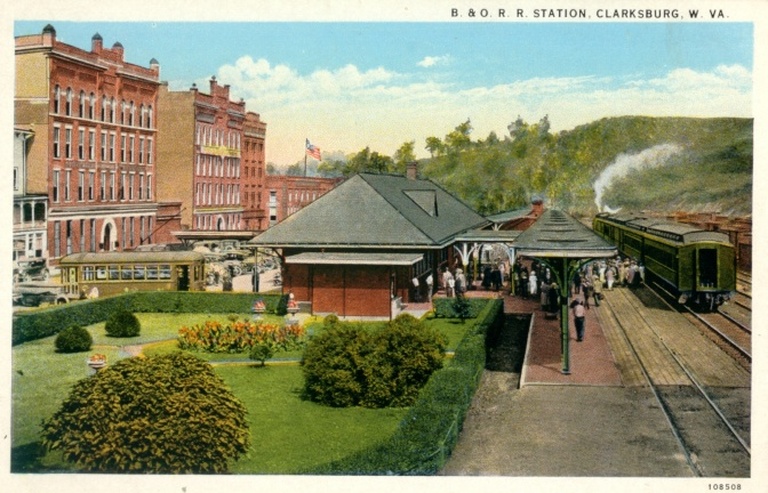

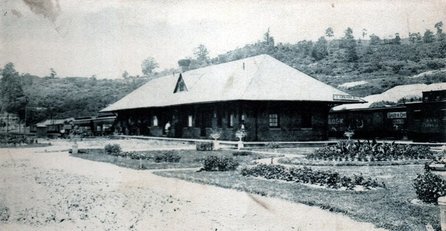

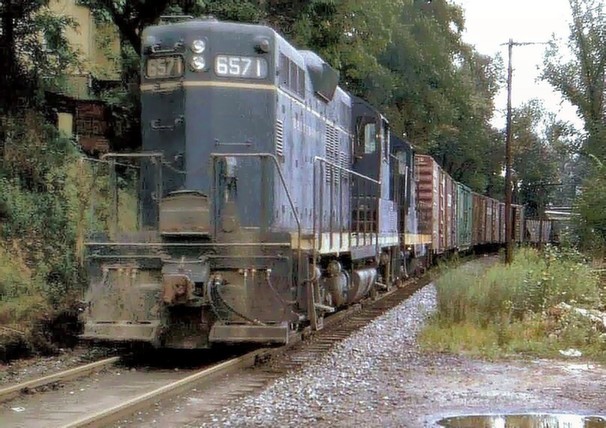

The interurban Monongahela West Penn extended a branch from Clarksburg to serve the Wolf Summit area during the early 1900s and it remained a B&O passenger flag stop into the 1950s. Now far removed from its industrial past, today Wolf Summit is presently the east terminus of the North Bend Rail Trail.