Kanawha and West Virginia Railroad

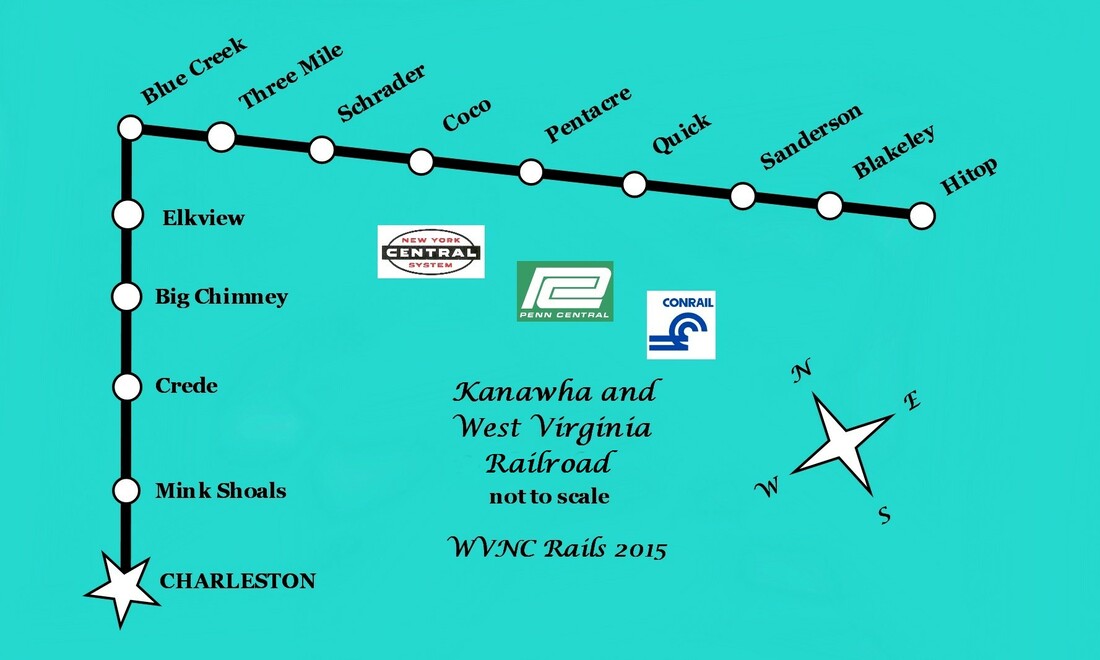

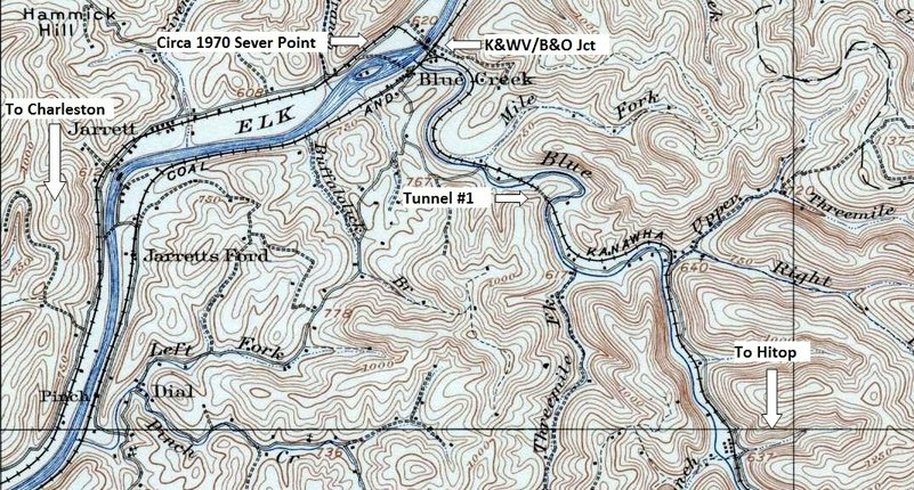

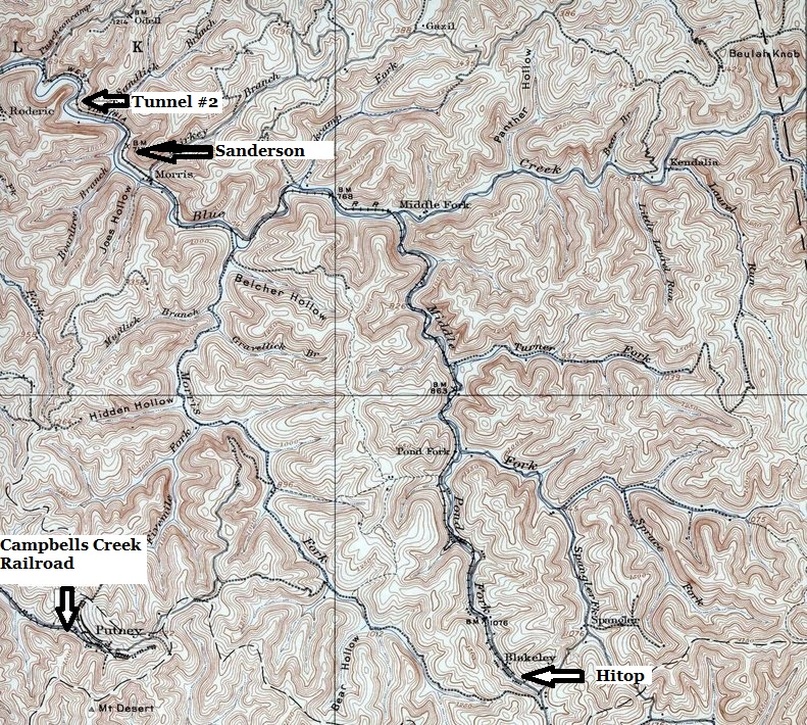

A customized not to scale map of the Kanawha and West Virginia Railroad from Charleston to Hitop. Selected town and place names are listed as well as the successor railroads to the K&WV that paralleled the Elk River and Blue Creek for its total length. Dan Robie 2015

Overview

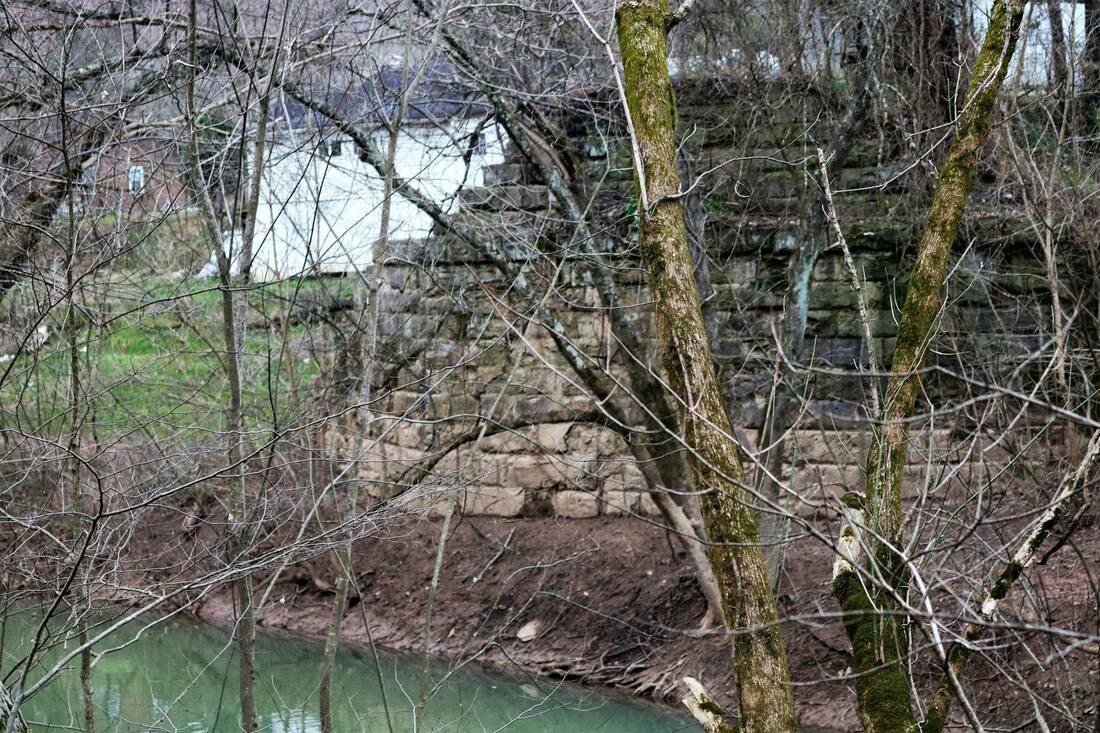

Casual observers driving from Charleston on US 119 headed towards Clendenin may spot telltale clues of the Kanawha and West Virginia Railroad but they are few in number. As they pass by the residential areas of Elk Hills, Mink Shoals and the tight confines adjacent to Elk River, there is barely any evidence that a railroad ran through here. Only upon arriving at Big Chimney and into Elkview does this piece of the past become more obvious as remains of the right of way and bridge piers left standing at creek crossings offer a residual look of what was. In earnest, it is at Blue Creek where the tracing of history readily appears to the eye as remnants of the K&WV are visible as the line followed the Blue Creek basin through small communities until reaching its terminus at Blakely and Hitop.

This particular railroad is an anomaly when studying the general rule of the life span of branch lines. Typically, it is the extremities of a route that are abandoned first and the line regresses or shrinks towards its point of origin. The Kanawha and West Virginia did the exact opposite because of external developments and by virtue of an alternate route available. During its construction during the early 1900s, its objective was to tap the coal and timber of the Blue Creek basin. Not known at the time was that the line had actually been constructed over a gold mine---black gold, that is. Within a decade of its inception, the great Blue Creek oil field was discovered and it was literally drilled alongside the right of way. This boom lasted for a few years and the railroad slowly returned to its status as a coal hauler with minute amounts of manifest sprinkled within. The K&WV remained a passenger hauler mainly due to the remote area it served with limited access and ran dedicated "school" trains lasting into the early 1960s.

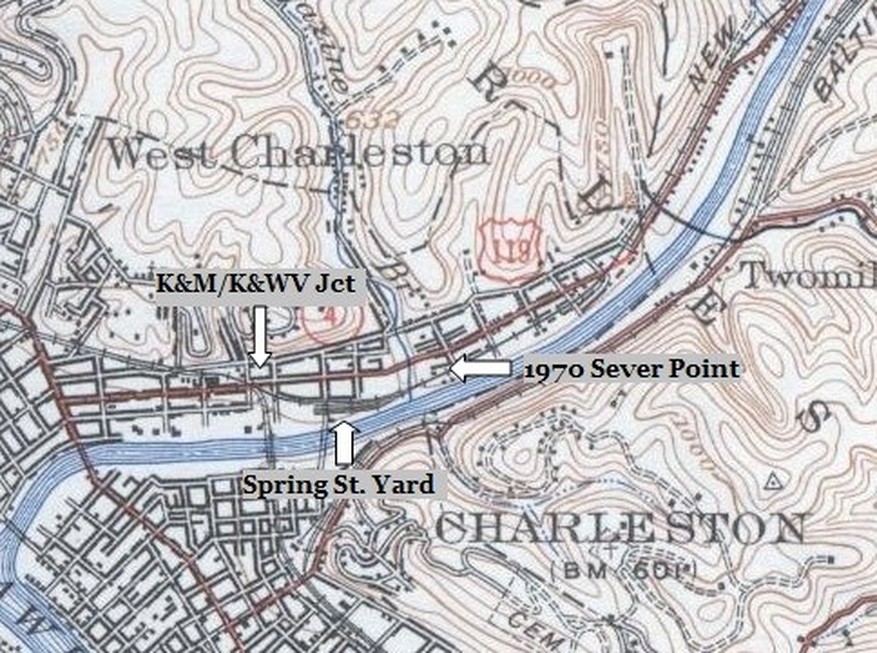

A mere 34 miles in length, the section from Blue Creek to Blakely generated the overwhelming amount of revenue and is the most familiar. Charleston to Blue Creek contributed to the passenger base but little on line freight business lay within this region outside of the capital city itself. The K&WV utilized a small yard at Spring Street in Charleston and a few trackside shippers in the vicinity that continued into the Penn Central era. To be sure recorded documentation and historical images of this line are rare as the route was largely overlooked by rail enthusiasts and historians.

Now dormant for a quarter century, what remains of the K&WV is in wretched condition. Track is still in place from Blue Creek to Hitop although there are sections that have been removed. Charleston to Blue Creek is a distant memory as this stretch of railroad was abandoned and removed circa 1970. Plans of resurrection flourished in 2010 with the announcement of a proposed railroad christened as the Charleston, Blue Creek, and Sanderson Railroad and the reopening of mines along the Blue Creek drainage. This line would use the former B&O from Charleston to Blue Creek and henceforth to Sanderson via the former Kanawha and West Virginia (NYC). The plans for rebuilding this line and resumption of mining along Blue Creek did not materialize and the furor faded into the background. Whether the CBC&S is ever built remains to be seen.

In one respect, this page can be considered a companion piece to B&O Charleston Division Part I--Charleston to Queen Shoals. The histories are similar and actually intertwine, particularly from the Penn Central era until both ceased rail service. References to B&O will be frequent and both pieces on this web page can be cross referenced. While some replication may occur, I will attempt to minimize it and especially in the area of image use. Archival photos on this page will also contain glimpses of B&O predecessor Coal and Coke Railway.

K&WV to Conrail

The beginnings of the Kanawha and West Virginia Railroad were complex in corporate structure as it involved multiple parties and the transferring of ownership. More indicative of modern day mergers and holdings, the melting pot that became the K&WV is a story that would impress the most astute of attorneys.

Initially incorporated as the Imboden and Odell Railroad in 1903 and lasting until 1905, the tiered structured ownership through holdings went as follows: The Kanawha and West Virginia Railroad, controlled by the Kanawha and Michigan Railroad (K&M) which in turn, controlled by Toledo and Ohio Central Railway, of which itself was a subsidiary of the New York Central Railroad. Of note is a smaller disconnected section of the Kanawha and West Virginia Railroad that was constructed to the east in Nicholas County. This piece of railroad was approximately four miles in length --originally planned as an extension over the Blue Creek divide---and connected the towns of Belva and Swiss of which access was over the Kanawha and Michigan (K&M) via Gauley Bridge. It was planned to physically connect this small segment to the Charleston-Blue Creek route but it was never realized. By 1938, the K&WV, in addition to the K&M, was outright consolidated into and operated by the New York Central.

Initially incorporated as the Imboden and Odell Railroad in 1903 and lasting until 1905, the tiered structured ownership through holdings went as follows: The Kanawha and West Virginia Railroad, controlled by the Kanawha and Michigan Railroad (K&M) which in turn, controlled by Toledo and Ohio Central Railway, of which itself was a subsidiary of the New York Central Railroad. Of note is a smaller disconnected section of the Kanawha and West Virginia Railroad that was constructed to the east in Nicholas County. This piece of railroad was approximately four miles in length --originally planned as an extension over the Blue Creek divide---and connected the towns of Belva and Swiss of which access was over the Kanawha and Michigan (K&M) via Gauley Bridge. It was planned to physically connect this small segment to the Charleston-Blue Creek route but it was never realized. By 1938, the K&WV, in addition to the K&M, was outright consolidated into and operated by the New York Central.

|

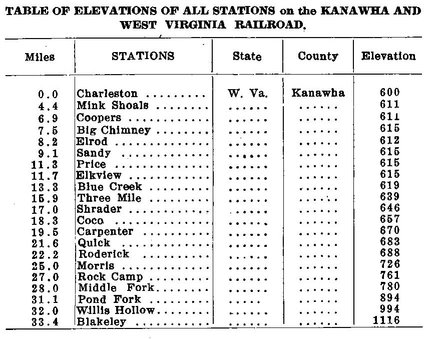

A 1922 listing of the Kanawha and West Virginia Railroad stations, mile post locations, and the elevation above sea level. The majority of these locales are place names on the railroad in regards to passenger train whistle stops. Flag stops were the rule to stop only if passengers wished to board or detrain at the specific locations. Railway Journal Table

|

Construction of the 34 mile long railroad from Charleston to Blakeley was also completed in phases with the Blue Creek to Quick section built and completed 1903-1905. Charleston to Blue Creek and Quick to Blakeley were constructed in the years spanning 1905-1906. With the completion of the Elk River bridge, the railroad was operational in its entirety by 1907. Two wyes were constructed on the route to facilitate the turning of steam locomotives--one in Charleston adjacent to Magazine Branch and the other to the west of Blakeley. Passing sidings were constructed at Quick, Morris (west of Sanderson), Middle Fork (east of Sanderson), and Blakeley. These sidings served a dual purpose to allow a passenger train to pass a coal train as well as for locomotives to runaround a cut of hoppers to and from the mines. Curiously, there is no apparent evidence of any such sidings existing between Charleston and Blue Creek. This is from both a cartography record and visual inspection of the right of way. When the K&WV first laid rails in Charleston, there was no yard; within several years, one had been constructed at Spring Street to stage cars to and from the Blue Creek region.

|

Natural obstacles were overcome with bridges--many as matter of fact. No less than thirty bridges spanned Blue Creek and its tributaries. The Elk River bridge and creek crossings on the line between Charleston and Elkview, though fewer in number, increased the total number. Construction of these bridges was a varied sort consisting of truss, plate, trestles and combination trestle/bridge spans. Tunnels at Three Mile and east of Quick, respectively, were drilled during construction of the line. Although relatively short in length, the K&WV climbed substantially in elevation from Charleston to Blakeley. From Charleston at 600 feet above sea level to Roderick at 688 feet was modest---the emphatic climb began there until reaching Blakeley at 1116 feet.

The formative years of the Kanawha and West Virginia Railroad were during its infancy when sources of revenue were more diverse. Built to tap the timber stands and coal seams of the Blue Creek basin, fate also intervened with the discovery of the great Blue Creek Oil Field in 1912 providing the railroad rich revenue from the black gold beneath its surface. Oil derricks sprang up like mushrooms in any available space including land adjacent to the railroad right of way. Although the oil boom had subsided by 1920, it was still pumped in moderate quantities. Another major contributor to growth along the K&WV RR was the Blue Creek Coal and Land Company which owned large tracts of land developed for mining

|

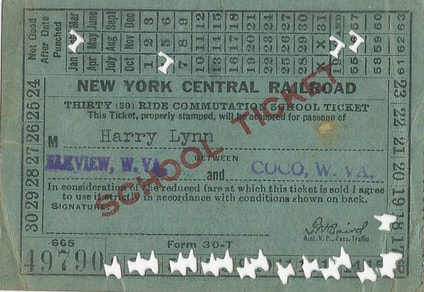

From the World War II era, the New York Central, now the outright operator of the route, operated coal and passenger trains between Charleston and the Blue Creek drainage extending into the 1960s. Coal traffic was subject to ebbs and flows, demand of the present economic conditions, and of course, stability of unionized labor relations. As was the general pattern of passenger rail, ridership declined in the post- World War II era although the K&WV, due to the demographic and topographic nature of its domain, continued to operate longer than most secondary and branch lines. Once steam power disappeared and train sizes decreased during the early 1950s, the New York Central began running a RDC (rail diesel car) to serve the remaining passenger base. This was essentially a bus on rails for it was a single powered car with crew and passenger seating. Of special note with this operation was the "school" runs that transported students to and from the communities of Blue Creek to Elkview.

|

A school ticket to ride the New York Central between Elkview and Coco during 1956. Student passengers accounted for a large percentage of ridership. My thanks to Harry Lynn for contributing a scan of his ticket for this page.

|

The most significant change to occur along the former Kanawha and West Virginia was during the late 1960s when the section of line between Charleston and Blue Creek was filed with the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) for abandonment. Several factors were at play during this time period that resulted in the closure and subsequent removal of track. First, New York Central had suffered numerous derailments on the line that often affected highway traffic on US 119. Maintenance was minimal and lighter weight rail had not been replaced as equipment became larger and heavier. Second, there was no online revenue generated from outside the Charleston city limits to outskirts of Blue Creek rendering the decision to remove the line easier. Finally, trackage rights were negotiated and obtained on the B&O from Charleston to Blue Creek thereby providing an alternative route. A connecting track at Blue Creek enabled trains to diverge from the B&O onto the remaining K&WV track along the Blue Creek watershed. In addition, two customers on the opposite bank of the Elk River could still be served via this route since the bridge crossing the river was still intact. By 1968 and now into the Penn Central era, coal traffic used the B&O from its junction with the PC at Capitol Street to Blue Creek. Although the K&WV route was officially abandoned in 1967, I have memories of ties and rail stacked at various locations circa 1970, a date used on this page as a reference of changed operations.

Another factor to consider regarding the abandonment of the K&WV from Charleston to Blue Creek was the planned development of the Interstate Highway system through the West Side of the capital city. A substantial section of residential and commercial neighborhood bordering Pennsylvania Avenue in Charleston was razed for the interstate construction which included the area extending to Mink Shoals. The K&WV right of way also paralleled Pennsylvania Avenue (US 119 outside of Charleston limits) and it was obliterated by highway development. Had the line not been abandoned in 1967, it certainly would have faced the same fate within a few years.

The yard at Spring Street was no longer used for its intended purpose once the K&WV line was cut. Trackage remained in place for several years although the yard was void of cars excepting for a gravel operator located on the side adjacent to Elk River. Occasional hopper cars would spot here in addition to warehouses east of the yard near the mainline sever point receiving boxcars. There was also a junkyard located near the former K&WV junction with the Penn Central mainline. By the onset of the 1980s, all of these shippers were gone.

My personal K&WV recollections are vague of the 1960s but firmly entrenched from the mid 1970s. Penn Central GP7s and GP9s would work the warehouses switching boxcars and the junkyard moving gondolas. Fond memories in this neighborhood spent with my father still resonate today. He would tell about busier times at the Spring Street yard and of trains running beside US 119 to Big Chimney and Elkview. There were the trips to the Big Star supermarket on Bigley Avenue and the stops at the Ashland gas station on Spring Street for fuel and a cold drink. Not directly linked to K&WV rails but in proximity were the outings at Big Toes junkyard---which had everything imaginable--- along the river and the Fountain Hobby Center. And then there is the unforgettable mouth -watering aroma of the Purity Maid bakery beside the Penn Central main at Bigley Avenue. None of these businesses remain today but for the Fountain Hobby Center.

During the 1980s, Conrail ---now the successor to Penn Central---continued to run coal trains to the Union Carbide mines along Blue Creek and switch the Clendenin Lumber Company and Halliburton. These runs averaged about two per week and continued until near the end of the decade. The mines either closed or ceased using the railroad altogether. Clendenin Lumber had closed its operation at Blue Creek and only Halliburton remained. It subsequently shifted its transport exclusively to truck effectively ending all revenue sources for the railroad. In Charleston, the few shippers that were located at the vicinity of the Spring Street yard either vanished or switched to trucks. The track here lay dormant although most of the rails were removed from the yard itself. The only evidence that multiple tracks existed were the rails embedded in the Spring Street asphalt. By the 1990s, all remaining track was removed and a new Foodland supermarket built upon the real estate once occupied by the K&WV yard. Few traces of the railroad can be found here today.

Charleston

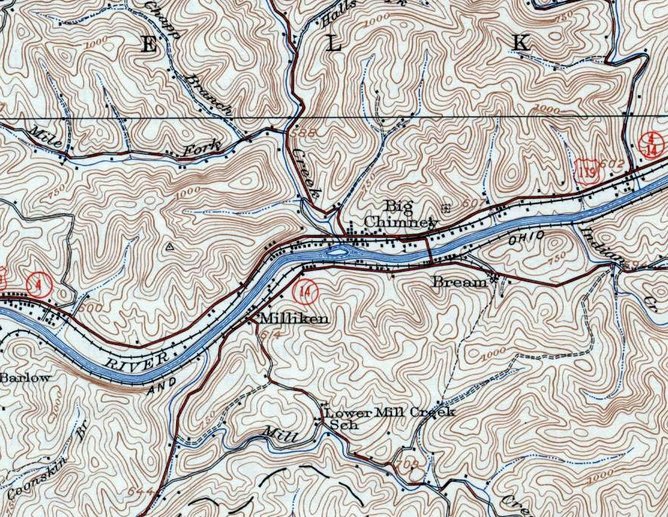

1935 topographic map focusing on the Elk River area of Charleston. Immediately north of the river is the Kanawha and West Virginia (K&WV) connection to the Kanawha and Michigan (K&M) both of which would become New York Central (NYC). The Spring Street yard is to the east and the railroad parallels Pennsylvania Avenue as it moves east. Also indicated is the circa 1970 sever point--intersection of Mary Street and Pennsylvania Avenue--- where the track was cut and removed from this location to Blue Creek.

The K&WV was a railroad of tight confines. Its right of way fit snugly between roads and river, streets and neighborhoods, highway and hillsides, creeks and bluffs. Add to that within the city of Charleston, cramped locations also included street borders and running between buildings. Settings such as these highlight increased awareness at immediate surroundings from an operations perspective; for the astute rail enthusiast or modeler, an added level of interest and character.

|

Modern times know this only as a curve beneath the Interstate 77 bridges north of the Elk River bridge on the Kanawha River Railroad. Few telltale signs remain to indicate this was the junction of the K&WV with the K&M (NYC) main. The track diverged to the left beyond the far pier as it crossed Pennsylvania Avenue. An auxiliary track also paralleled the NYC main here as well. Dan Robie 2019

|

The route of the K&WV marked with green inserted into a view of contemporary Charleston for comparison. This area includes its connection to the New York Central main (Kanawha River Railroad today), the former yard location, and where street trackage began on Pennsylvania Avenue. A few modern locations are labeled for reference.

|

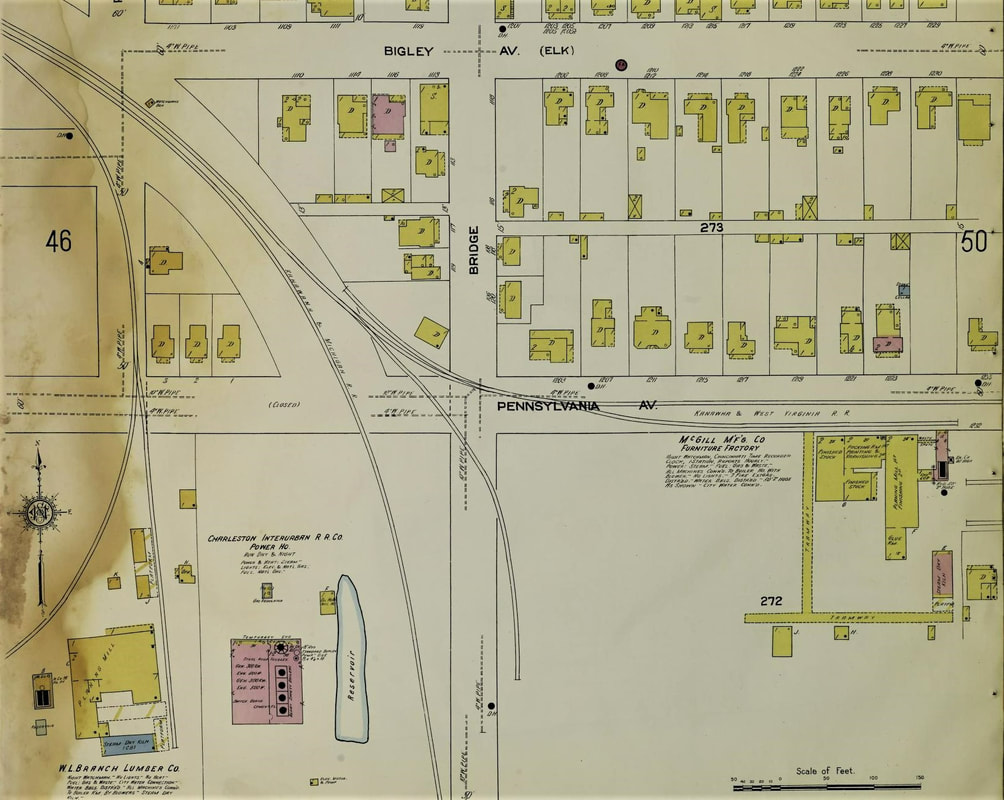

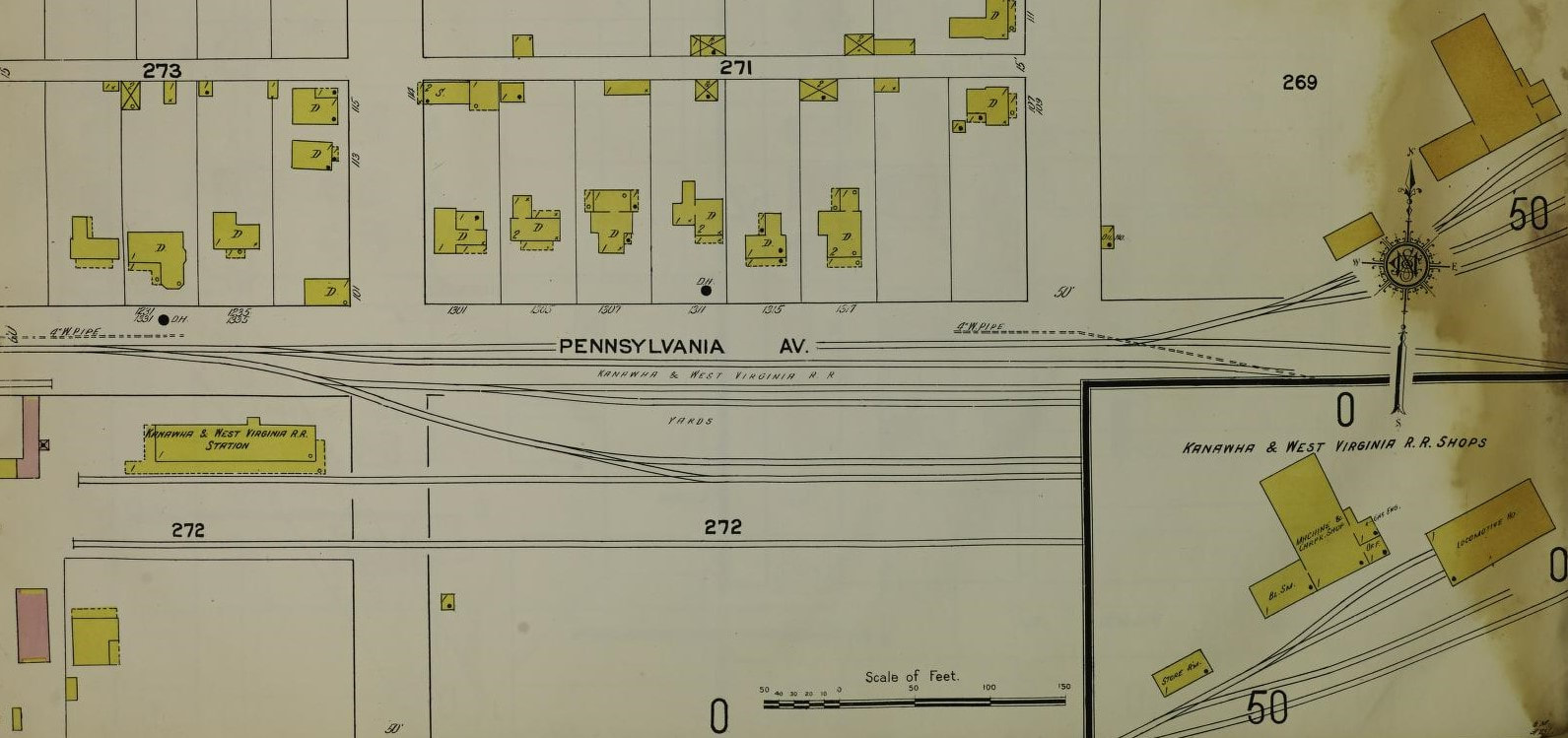

The junction area of the Kanawha and West Virginia Railroad with the Kanawha & Michigan Railroad as it existed in 1912. Both mains paralleled for a brief distance from Pennsylvania Avenue to beyond the Bigley Avenue grade crossing. Also visible is the McGill Manufacturing Company (furniture) was an early shipper located along Pennsylvania Avenue. The Interstate highways dominate this area today.

|

From whence the K&WV began. The mainline diverged from the K&M (present day NS) through the grass median ahead and continued through the grassy area in the foreground. From the location of this image, a track diverged to the left to serve a junkyard during the latter years of the Penn Central. Dan Robie 2005

|

The mainline paralleled Pennsylvania Avenue through this scene--in fact, so close, the edge of the ties bordered the asphalt. A passing siding ran adjacent to the main here also serving as a runaround. Spring Street is in the distance. Dan Robie 2005

|

Along Pennsylvania Avenue were the facilities of the K&WV. Its station. yard, and shops occupied the area bordered by Spring and Ash Streets. Virtually no trace of the railroad remains in this area today except for a section of roadbed paralleling Pennsylvania Avenue.

What little manifest the K&WV and in the later years, the New York Central, moved was effectively confined to the city limit of Charleston. Distribution warehouses were constructed in the vicinity of Pennsylvania Avenue at a quadrangle to Bigley Avenue and were served by boxcars. Earlier years witnessed a freight house that occupied space between Pennsylvania Avenue and the Spring Street yard. A junk dealer was served by a spur from the K&WV main near its junction with the K&M/NYC main. In the old Spring Street yard along the bank of the Elk, a small concrete preparation loader was active for a few years after the K&WV main to Blue Creek was cut. The majority of these shippers remained into the Penn Central era but were gone by the onset of Conrail. All remaining track in this area was completely removed circa mid 1980s and by the 1990s, the Foodland supermarket occupied the former yard area. Other developments and street expansion work virtually obliterated the former K&WV right of way in the city limits.

Capitol Street terminal and Staging (Post 1967)

The Broad Street grade crossing as it was in 1970. A Penn Central coal train is diverging from the B&O in Charleston with loads from the Union Carbide mines on Blue Creek. The K&WV between Charleston and Blue Creek now abandoned, the B&O now fills the role between the two points. In the background is the old K&M/NYC freight terminal---today it is the Capitol Street Market and the Interstate ramp would now dominate this view. From the zebra stripe based grade crossing flashers to the PC GP9, the scene harkens of boyhood memories for this observer. Image Jerry Taylor/courtesy Indiana University Press. All rights reserved.

These two views are from the Conrail era and show the empty hoppers that were staged for the Blue Creek trains on the East End of Charleston. At left, looking south between Ruffner Avenue and Elizabeth Street. Only the main line remains here today. The scene at right is to the north from the Ruffner Avenue grade crossing and some of this trackage is also gone today. Both photos Dan Robie 1983

After the demise of the New York Central yard at Spring Street, it and the successor Penn Central faced a problem with yard storage capacity. The Capitol Street yard and freight terminal were often congested with manifest cars and the resulting problem was how to stage coal empties bound for the Blue Creek mines. An alternative was to stage these cars on the storage tracks between Elizabeth and Morris Streets in the East End of Charleston. This remained a common practice from the 1970s until the closure of the Union Carbide mines along the Blue Creek drainage by 1990. Whether there was any consideration of using the dormant B&O yard tracks at Slack Street for this purpose is uncertain. During that era, most of the yard tracks remained intact with enough capacity for empty hoppers bound for Blue Creek.

North Bank of the Elk

A low quality but rare photo of the West Side of Charleston taken from the hill above present day Westmoreland Road. Captured in this circa 1930s scene is a train working the Spring Street K&WV yard at right. Detail is not crisp but the K&WV freight house is visible at extreme right as is the Spring Street bridge. On the opposite bank of the Elk River is the B&O Railroad, the rock quarry, and buildings such as the old water plant and Kanawha Brewery. Image courtesy Kanawha County Public Library

|

A view south along Pennsylvania Avenue adjacent to the West Virginia Water Company. The railroad passed through the area at center (trees) and turned on what is the grassy area at left. Dan Robie 2019

|

Opposite view looking north along Pennsylvania Avenue. Railroad right of way was at right and in the distance by the bright white building, it became street trackage. Dan Robie 2019

|

At first glance the reader may wonder about the inclusion of these two photos. Portrait photos of the parents of the contributor, they also capture a lost piece of history often found in the background of such images. Taken along Pennsylvania Avenue in 1964, both provide a glimpse of the K&WV street trackage beyond the vantage point of the two previous contemporary images. New York Central trains to and from Blue Creek still passed at this date but for only three more years. Images contributed by Jeffrey Morris

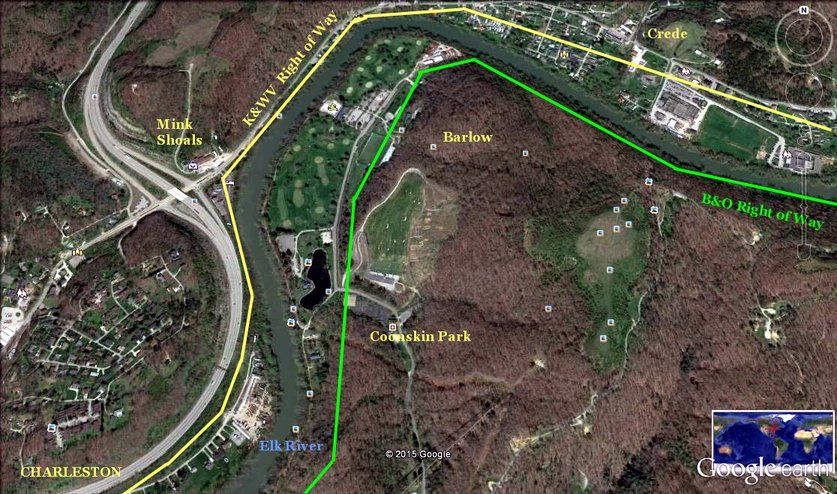

Google Earth image of the area immediately east of Charleston limits. On the north bank is the path of the long gone K&WV right of way through Mink Shoals into Crede. Interstate construction and development has obliterated most traces of its existence. On the south bank the B&O through Barlow and Coonskin Park is indicated as a correlation of two once moderately busy railroads that flanked the Elk River.

|

The subject here is the long ago family home of the photo contributor's mother but it also captures the K&WV east of Charleston at Conner Drive. This was at the grade crossing of US 119 and dates to at least to the early 1960s before Interstate highway construction razed it. Image courtesy Mark Layton

|

A rare photo that captured an excursion train on the K&WV during the late New York Central Railroad era. This image is undated but is probably late 1950s time period and the scene is at the trestle that spanned the mouth of Mink Shoals Creek. The occasion is not known---perhaps an excursion associated with the Union Carbide camps along Blue Creek. Pictured is the NYC RDC (rail diesel car) used for passenger service on the route in addition to a gondola and coach. Image courtesy mywvhome.com

|

Perhaps the greatest oddity about the Kanawha and West Virginia Railroad is that the most accessible region it traversed is also the least documented. The railroad outside of Charleston to Blue Creek paralleled US Route 119 as it passed through Big Chimney, Elkview, and smaller communities along this stretch. Yet photographs of the railroad through this sector are scarce almost to a point of non-existence.

|

Abandoned K&WV right of way in the community of Crede. Most visible remaining traces are where the line passed through residential areas. Dan Robie 2010

A northbound view along the former right of way at Crede. Property owners have converted it to a greenery causeway of trees and manicured landscape. Image courtesy Brad Mills

|

Telltale signs of the past still remain. This New York Central Railroad right of way marker still stands vigil as a reminder of a property boundary from long ago. Image courtesy of Brad Mills

Coal trains from the Blue Creek basin once passed over this block stone culvert bridging a brook in Crede. Many of the homes in this community were in existence when the railroad was active. Image courtesy of Brad Mills

|

Big Chimney and Elkview

|

A 1935 MyTopo map of the region from Crede to east of Big Chimney. The K&WV---NYC controlled by this date---parallels the highway and Elk River as it passes through the communities.

|

A New York Central passenger train runs through Big Chimney headed for Charleston. Thanksgiving 1950 witnessed a fluke winter storm that dumped heavy snowfall. Image Michael Ross collection

|

Railroad remnants at Big Chimney. Bridge abutments still flank both banks of Coopers Creek in contrast to much of the former right of way reclaimed. Dan Robie 2005

Among the myriad of West Virginia communities with uniquely colorful names is Big Chimney, located along the Elk River approximately nine miles east of Charleston. Situated at the mouth of Coopers Creek, the discovery of oil here predated the great Blue Creek field a few years later. Oil derricks were located along the Coopers Creek drainage and the area was the site of a salt furnace with a large chimney from which the community took its name. The salt production was short lived; ironically, it was the oil that contaminated the underground salt and rendered it useless.

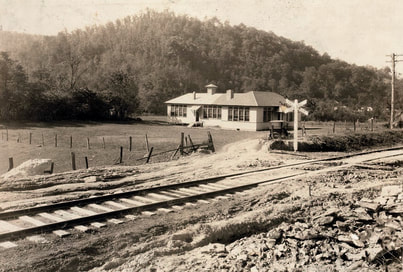

A view looking southwest along the K&WV at Big Chimney. This circa 1910 image offers a glimpse of the Big Chimney Grade School and the bottom land along the river as it looked a century ago. Architecture once reflected pride in design such as the school house and railroad crossbucks---contrast that to the rather utilitarian blueprints churned out today. To the rear of the school can be seen the community of Bream across the Elk River. Image Library of Congress.

Big Chimney was a whistle stop during the K&WV era continuing into the twilight years of passenger service on the New York Central. Its depot, long since vanished, was located east of the mouth of Coopers Creek. There is no evidence of any shipper located here aside from the salt works during the early 1900s and the transport of oil drilled in the area. Its depot, long since vanished, was located just east of the mouth of Coopers Creek.

Coal mining played a large role in the early 20th century in the Big Chimney vicinity. A number of mines were located here and certainly utilized the railroad to any necessary extent. Active coal operators here during the 1920s include the Davenport Coal Company, Empire Coal Mines Company, Granny Branch Coal Company, Mandt Mining Company, Pen-Mar Coal Company, and the Ray and Burdette Coal Company.

Through the lazy sway of the trees and right of way reclaimed the spirits of the K&WV linger. Fifty years hence since the last New York Central trains to and from Blue Creek passed within the residential district of Big Chimney. Both images by Earl Fridley

The railroad paralleled US 119 along its trek from Big Chimney to Elkview and traces of the right of way are still discernable here. It was this stretch of track that became notorious for derailments because when one occurred, the result was coal dumped in the highway obstructing vehicular traffic. As the track was literally adjacent to the road in this area, this was a major concern that ultimately resulted in pressure from state agencies for the New York Central to solve the problem. The NYC elected to solve the issue permanently--it negotiated trackage rights over the B&O on the opposite side of the Elk rendering the K&WV route between Charleston and Blue Creek dispensable.

|

Abutments also remain at the Little Sandy Creek crossing by the K&WV Railroad between Big Chimney and Elkview as sentinels to its one time existence. The cold weather months offer the best time for a photograph of these structures. Image Jeanie Droddy/Herb Wheeler collection

|

In better condition is the opposite abutment in a photo taken during low water. Trains crossed the creek here on a deck bridge span. Image by Earl Fridley

|

|

Elkview once was referred by the name of Jarrett and the place name still existed during the early years of the K&WV. Although there is no evidence of any large shippers having been located here, the railroad served the community by virtue of a depot and any associated business during the great oil boom. During the passenger era, it was among the prominent stops on the route and is fondly remembered during the twilight years with the "school" train. Elkview High School was a targeted destination for these runs to and from the Blue Creek watershed.

Now gone for nearly fifty years, traces of the railroad right of way are still visible and most notably, the area between Elkview and Blue Creek. The depot remains as the last landmark on the railroad between Charleston and Blue Creek and has housed various businesses throughout the years. |

The K&WV depot at Elkview still stands as a sentinel to another time. It has been altered in appearance and served in various functions since its railroad days. It was a pizza parlor when this image was taken. Dan Robie 2005

|

Elkview High School in a scene that perhaps dates to circa 1960. Students from the Blue Creek drainage rode passenger trains for nearly 35 years from 1925 to 1959. Steam power with coaches was the mode during the earlier years then a RDC (rail diesel car) sufficed in the final years. Image courtesy Earl Fridley

Blue Creek Region

This 1907 MyTopo map diagrams the K&WV on the eve of its heyday during the oil boom. Centering on the Blue Creek region, the railroad is depicted from west of Jarrett (Elkview) to an area beyond Blue Creek along the namesake stream. This also reveals the relationship of the Coal and Coke Railway--later B&O-- that witnessed both conflict in the early years to cooperation during the final years.

In the grand scope of railroad history, the Kanawha and West Virginia is little known outside the realm of West Virginia or to students of New York Central ancestry. Its small size accounted for the scale of the obscurity and once absorbed into the New York Central, it was a tiny piece in a giant railroad system. But to those who lived near it, rode or worked its rails, there is no doubt as to the heart and soul of the line. Mention K&WV and the immediate connotation is the Blue Creek region.

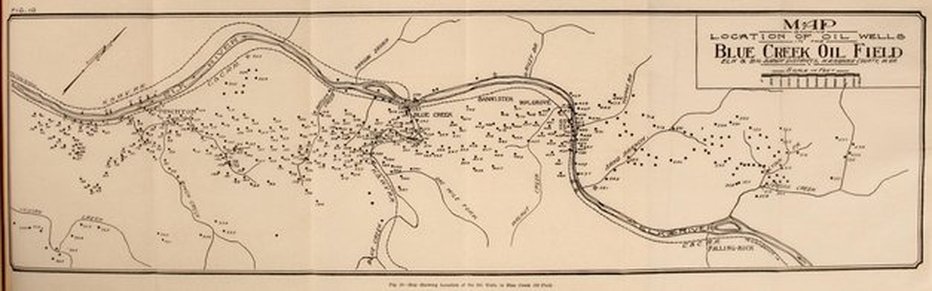

A period map during the peak of the Blue Creek oil boom indicating the location of individual wells. As fate and geology dictated, the south bank of the Elk River was the epicenter of the field and both the Kanawha and West Virginia and the Coal and Coke reaped the reward of increased carloads. West Virginia Geological Survey map

It is interesting to note that construction of the Kanawha and West Virginia began at Blue Creek in 1903 and was completed to Quick by 1905. This involved a dependence on the Coal and Coke Railway during this construction phase for material and is indicative of the connecting track between the two from the earliest years. The initial economic reason for building the railroad along the Blue Creek drainage was to tap timber stands and coal reserves. Timber was short lived as a source of revenue for the K&WV as it had effectively faded by the 1920s. Coal proved to last considerably longer with the final trains laden with black diamonds passing through Blue Creek circa 1990.

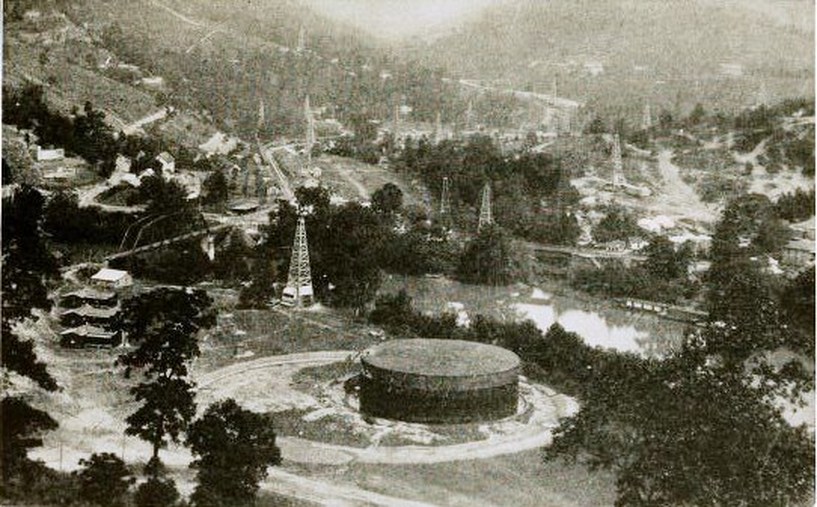

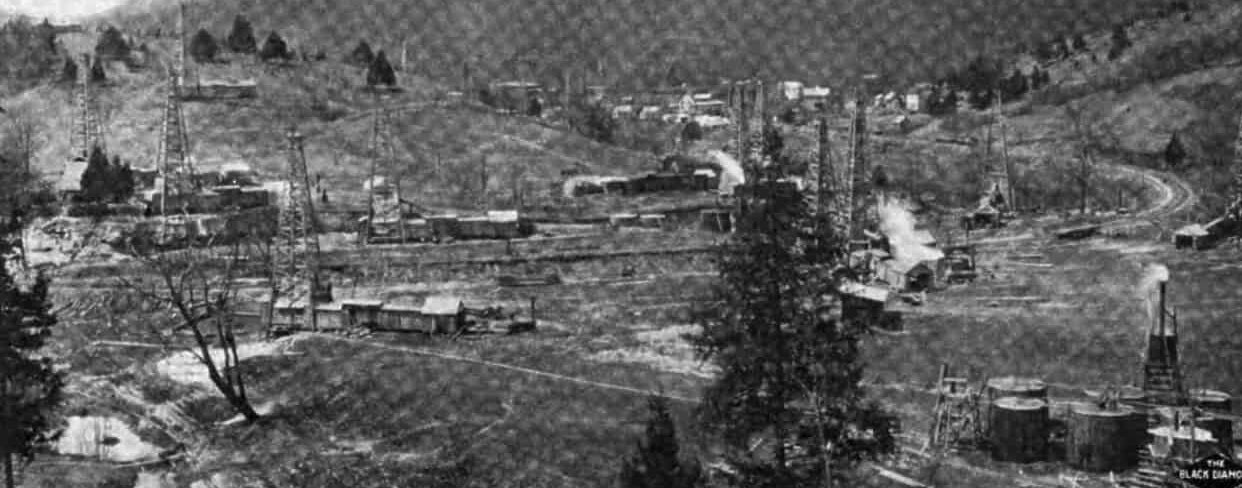

Exceptional image from 1913 depicting the Blue Creek oil boom in full glory. A plethora of oil derricks populate the landscape and a huge storage tank dominates the foreground. The K&WV Elk River bridge and right of way are visible at left as is the Coal and Coke Railway crossing of Blue Creek. Note the structures related to both the oil boom and the railroads. Image West Virginia Geological Surveys.

Manifest traffic on the K&WV was sparse outside the Charleston city limits. One shipper not related to coal was the Clendenin Lumber yard at Blue Creek which received boxcars for many years. At left, track is embedded in the asphalt at what once was the loading ramp. On the right the fence line marks the location of the former main parallel to US 119 looking back towards Charleston. Both images Earl Fridley

A circa 1970 view looking westbound across the K&WV (Penn Central at this date) bridge after a snow storm. The railroad between Charleston and Blue Creek was gone by this date but trains still crossed the bridge to serve Clendenin Lumber and Halliburton Industries. Buried beneath the snow in the foreground is the B&O junction on a diamond crossing. Image Lewis Gay Pauley/contributed by Earl Fridley

|

During the mid-1990s, a new road bridge was built across the Elk River and the old K&WV bridge was modified to accommodate vehicle traffic during its construction. This image was taken after it fulfilled that purpose and is awaiting demolition. Image courtesy Mike Thomas.

|

For the first time since 1907, a railroad bridge no longer spans the Elk River at Blue Creek. The old K&WV truss bridge, a fixture for nearly a century, meets its end as it plunges into the river below. Image courtesy Mike Thomas.

|

Blue Creek blossomed into full glory with the discovery of the great oil field in 1912. Oil wells were drilled in quantity extending west to the Pinch area and reaching Clendenin to the east. Well derricks rivaled trees as they were erected virtually everywhere the eye could gaze. The roadbed on the newly constructed K&WV had barely settled when the great boom arrived. As a result, both the Kanawha and West Virginia Railroad and the Coal and Coke Railway had precisely the right instrument in the right place and time to capitalize on this economic bonanza. Within this boom ensued a rivalry between the two roads, often bitter. The Coal and Coke had been completed first; when the K&WV was under construction, it had to cross the C&C at Blue Creek facilitating a crossing of the two on a diamond. Lease terms for this junction were construed whereby the K&WV paid the Coal and Coke but it failed to fully comply. As a result, conflict arose with the C&C ultimately removing the diamond climaxing a hostile situation between the roads. Eventually, an agreement was reached and the crossing was reinstalled and remained permanent.

|

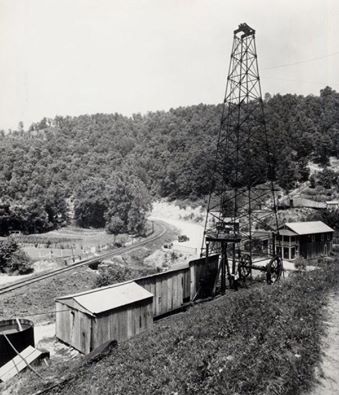

Brown #1 well along Blue Creek during the great boom era circa 1913. Image West Virginia Geological Surveys

|

The oil wells were literally everywhere space would permit during the boom years. Pictured here is the Skinner well just to the east of Blue Creek along the K&WV. Image courtesy Mike Thomas collection

|

The properties of the Standard Kanawha Coal Company were literal gold mines---black gold, that is. Not only was there the crude oil of the Blue Creek oil field but vast resources of gas and coal. This view is near One Mile during the height of the boom. Image West Virginia Geological Surveys.

In the years post-dating the oil boom, Blue Creek subsided in commercial importance to both railroads but remained prominent as a junction. B&O first took control of the Coal and Coke Railway before ultimately acquiring outright ownership of the line. Its passenger trains continued to stop as well as freight trains passing between Charleston and Gassaway. The K&WV continued running passenger trains between Charleston and the Blue Creek drainage and effectively relegated to a coal hauling road. In the years after the end of the oil boom to the World War II era, the tempo of traffic through Blue Creek remained consistent barring any economic ebbs and flows, particularly in regards to coal.

Note: Additional Blue Creek images can be found on B&O Charleston Division Part I-Charleston to Queen Shoals. Click here for the link.

Another boom era image taken along the Kanawha and West Virginia Railroad in the vicinity of One Mile Fork. Oil derricks straddle both sides of Blue Creek as the railroad sweeps on a curve. Railcars with supplies for the drilling occupy a siding and the creek channel appears to have been notched as a cut. Image West Virginia Geological Surveys

Passenger traffic lasted longer on the K&WV, now New York Central, than on the B&O. The last B&O passenger train called at Blue Creek in 1951 whereas the NYC continued running trains until 1962. As previously discussed, the trains remained on the NYC until this late date due to poor roads in the Blue Creek watershed whereby the trains--and eventually, a single RDC---served as a school bus on rails.

|

The area just east of Blue Creek referred to as One Mile. Growth choked and decaying, nature has reclaimed the right of way at a point once concentrated with oil wells. Dan Robie 2010

|

Looking at the west portal of Tunnel #1. Purely cut stone with no lining not uncommon in the mountains of Appalachia. Image courtesy Carlos Morris

|

|

The east portal of Tunnel #1 provides a good glimpse of the cut through solid rock and the tight clearance. Image courtesy Carlos Morris.

|

The second crossing of Blue Creek beyond the east portal of Tunnel #1. A tranquil scene that begs for the emergence of a train and a fishing pole. Image courtesy Carlos Morris.

|

From the early 1960s to the late 1970s, the frequency of trains decreased at Blue Creek. B&O ran a through train that returned the following day and coal traffic on the NYC fluctuated on demand with variances in the number of trains. This remained in effect into the Penn Central and Chessie System eras until the B&O was abandoned between Reamer and Hartland effectively ending Charleston service. The only remaining trains to pass through Blue Creek on B&O rails were the switching turns from South Charleston that served the Elk Refinery. Coal trains had turned from NYC to B&O rails since 1967 when the old K&WV from Charleston was abandoned but consequently had no impact on the number of movements. The K&WV Elk River bridge was still in service to serve a short stub of track along which were located Clendenin Lumber and Halliburton Industries.

|

Scenes such as this magnify the passage of time since coal trains last ran through here. Compared to most man made creations, an abandoned railroad track tends to blend into the surrounding scenery. Former K&WV rails near Three Mile along Blue Creek. Image courtesy of Harry Lynn.

|

More than twenty years since the last trains, small trees now grow between the rails. Moving south along Blue Creek at Three Mile. Image by Jeanie Droddy

|

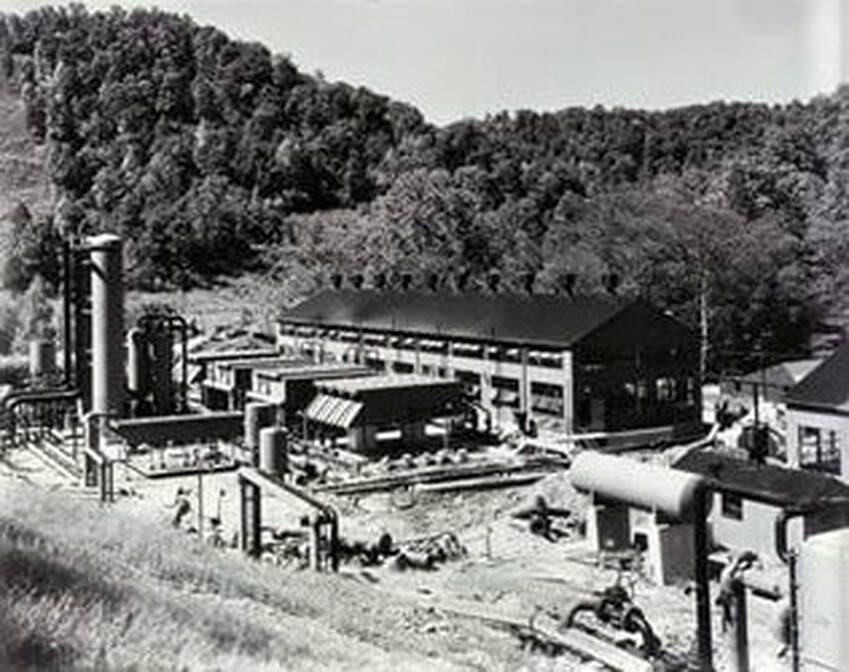

Gas compressors were built at various locations in the Elk River valley region. This photo is of the Columbia Gas compressor at Coco under construction that began operating in 1951. Image Jonathan Nooney collection

|

View of the bridge spanning Blue Creek at Milepost 18 east of Coco. The gas compressor site is just around the curve from this location. Image by Earl Fridley

|

The bridge at Coco has become a makeshift dam of sorts for fallen timber. Unfortunately, this will weaken it and ultimately result in its collapse. Image by Earl Fridley

|

|

The ex-K&WV Railroad is very much a fragmented railroad in its abandoned state. While most of the track is intact along Blue Creek, there are sections where it is removed such as this locale near Coco. Image by Earl Fridley

|

The narrow Blue Creek basin combined with twisting bends resulted in numerous railroad crossings of the creek. This view captures another span just west of Pentacre. Image by Earl Fridley

|

The atmosphere of mid-1950s Appalachia is captured in this scene along the K&WV at Quick. An RDC "Beeliner" is paused as a father has possibly boarded his child for Elkview High School. Or perhaps, maybe his wife headed to Charleston for some shopping. Long ago poignancy where only the memories remain. Image Richard J. Cook/ Allen County Museum

At Three Mile began the coal mining sector of the K&WV RR. An operation was opened here by the J. W. Miller Coal Company at Shrader. Mining also developed in the vicinity of Quick during the early years. Listed active mines from the 1920s at Coco and Quick include the Slack's Branch Coal Company and two mines of the Standard Kanawha Coal Company. In later years, Union Carbide also owned active mining interests in this vicinity as well.

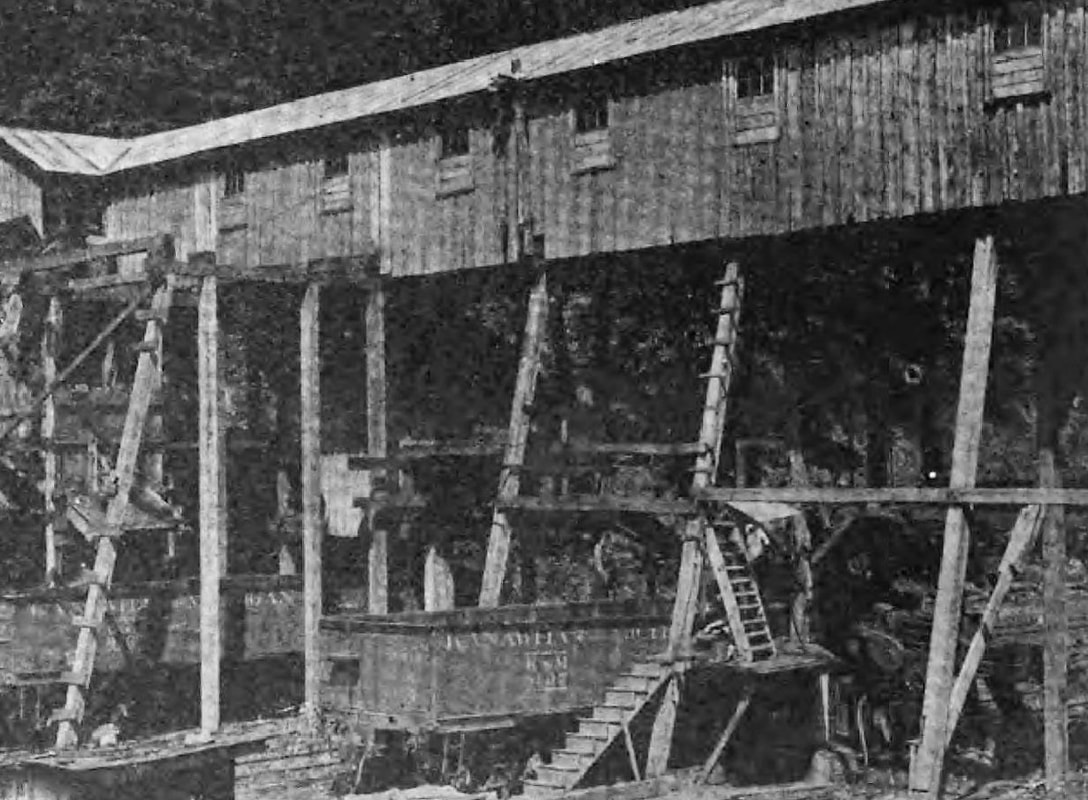

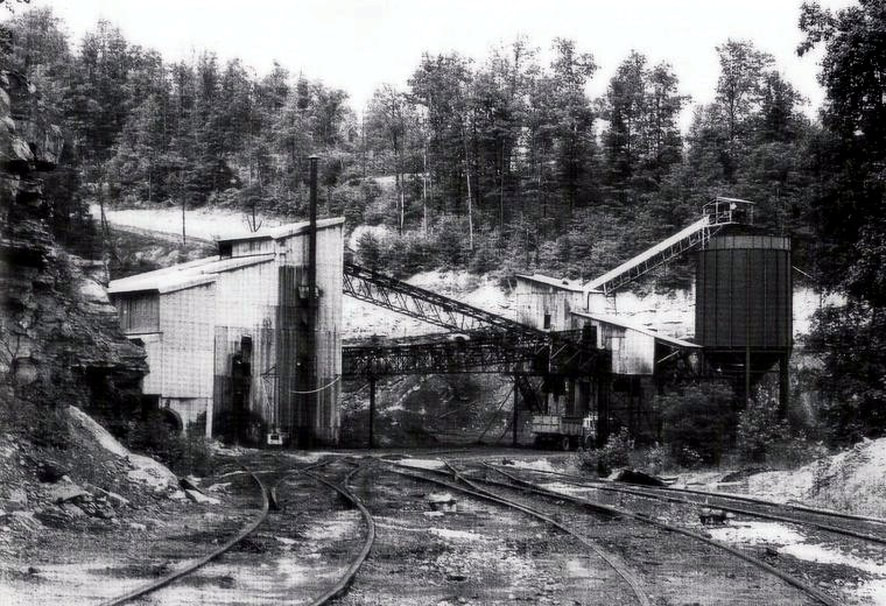

A tipple of one of the Standard Kanawha Coal Company mines near Quick as it was in 1914. Note the hoppers lettered for the Kanawha and Michigan Railway. Image from The Black Diamond

South to Hitop

The mountainous terrain of the Blue Creek watershed as traversed by the K&WV. Narrow valleys and tight curvatures defined the line as it passed through small mining communities laden with black diamonds. Other small coal hauling roads such as the Campbells Creek Railroad were in proximity separated only by the creek divides of the mountains.

The railroad from Blue Creek to Hitop was a crooked route paralleling and continuously crossing the creek for the right of way to best utilize the terrain. Built on tight curvatures and generally lighter weight rail, speeds and tonnage were restricted. The New York Central was plagued with derailments due mainly to light maintenance and a reluctance to upgrade the line with heavier rail. With the onset of Penn Central and its financial woes, this trend continued as the route was acknowledged as a maintenance nightmare. Adding to ongoing maintenance concerns with track, there were also the numerous bridges and trestles that compounded the problem. This does not even take into account repairs occurring from high water and washouts.

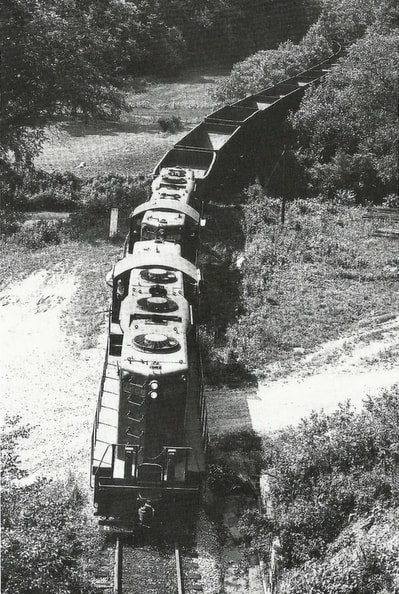

at Tunnel #2---1970A pair of Penn Central GP9s lead coal empties near Morris on the return to the mines in 1970. The photographer stood atop the west portal of Tunnel #2 to capture this scene. The tight and twisting nature of this line is in evidence looking back along the train. Image Jerry Taylor/courtesy Indiana University Press. All rights reserved

|

at Tunnel #2---2019Standing atop Tunnel #2 from the same perspective a half century later. No train has passed in nearly 30 years as time and nature have taken their toll on a rail line that has subsided into history. Image by Earl Fridley

|

Motive power used throughout the years was restricted to the limitations of the line. Since its construction was on lighter rail---such as 90 pound--and due to curvatures eclipsing 10 to 12 degrees, only light to medium size steam power could operate within these limitations. Upon the onset of the diesel era, four axle units were the norm. Typically GP9s from New York Central through Penn Central, the practice continued until the final years of Conrail with GP35 and GP40 class locomotives. Naturally, the tonnage of trains was adjusted within the specifications of the horsepower and tractive efforts.

|

Looking west from Tunnel #2, the railroad spans Blue Creek on one of its numerous crossings of the stream. The track in this scene presents the appearance of still active railroad. Dan Robie 2010

|

The west portal of Tunnel #2 to the east of Quick. This bore appears to have been relined at some point in the distant past. Dan Robie 2010.

|

The abandonment of the K&WV between Charleston and Blue

Creek in 1967 had no significant impact on the Blue Creek to Hitop sector. In

fact, it could be stated that in reality, the movement of trains actually

improved. Trackage rights over a better maintained B&O facilitated train

movement between the two points. If one negative aspect could be introduced, it

would be the frequent congestion and switching at the Capitol Street yard and

terminal that trains faced coming to and from the B&O.

|

Mile Post 21 near Quick. A relatively modern marker probably installed during the early Conrail era as a replacement for the original. Image courtesy Carlos Morris

|

An abutment remains from a long since vanished crossing of the aptly named Blue Creek near Quick. The bluish green hue of the water with rock and sandy creek bed is representative of shallow mountain streams in Appalachia. Dan Robie 2010

|

Once one left the concentration of oil derricks on the trek up the Blue Creek watershed, the railroad landscape transformed from that of the oil field to the coal mine. Mines of varying sizes in terms of tonnage capacity populated the small communities along the creek. Numerous mines of differing ownership were prevalent in the K&WV era lasting into the early New York Central period. By the time of the Penn Central and ending with Conrail, the remaining coal mining activity was firmly under the umbrella of the Union Carbide Corporation. During the early years, the destination of hoppers loaded with coal was more widespread. By the time of Union Carbide ownership, the coal trains were dedicated short runs to Kanawha River valley locations such as Alloy and Institute.

|

The railroad hugs the road as it snakes around the bend and into a cut at Kennedy Cemetery west of Sanderson. A telltale sign of why the track speed here was 10 MPH. Image courtesy Curtis Riffle 2005

|

Looking west at Sanderson. The switch stand for the siding is intact as the railroad disappears into a growth of trees ahead. Common pattern for the decaying track and right of way inactive. Image courtesy Curtis Riffle 2005

|

This trestle stands in a dilapidated state at Middle Fork as a harkening reminder that coal trains once traversed the upper Blue Creek basin. The region from Middle Fork to Hitop is where the mining first ceased and the railroad abandoned nearly 50 years ago. Image by Earl Fridley

In spite of operational hindrances, there is no question that this stretch of the route was the heart of the Kanawha and West Virginia Railroad. It was established as such from a revenue perspective during the early years continuing into New York Central ownership. Today, looking in the rear view mirror, it remains so in the cozy confines of nostalgia as memories flourish of a simpler time. Many regional residents recall with fondness the “school bus” trains that were first steam powered and at their conclusion, rail diesel cars (RDC) that culminated their runs in 1962. These were twice daily runs between Charleston and Hitop with Elkview High School the primary point of the school passenger base.

The tipple at Morris Fork as it appeared in 1970. Even though it is now the Penn Central era, the hopper cars still bear the paint of predecessor New York Central as many would continue to do. Morris Fork was a busy operation along Blue Creek and even at this relatively late date, still generated two trains worth of hoppers per day. Image Jerry Taylor/courtesy Indiana University Press. All rights reserved

|

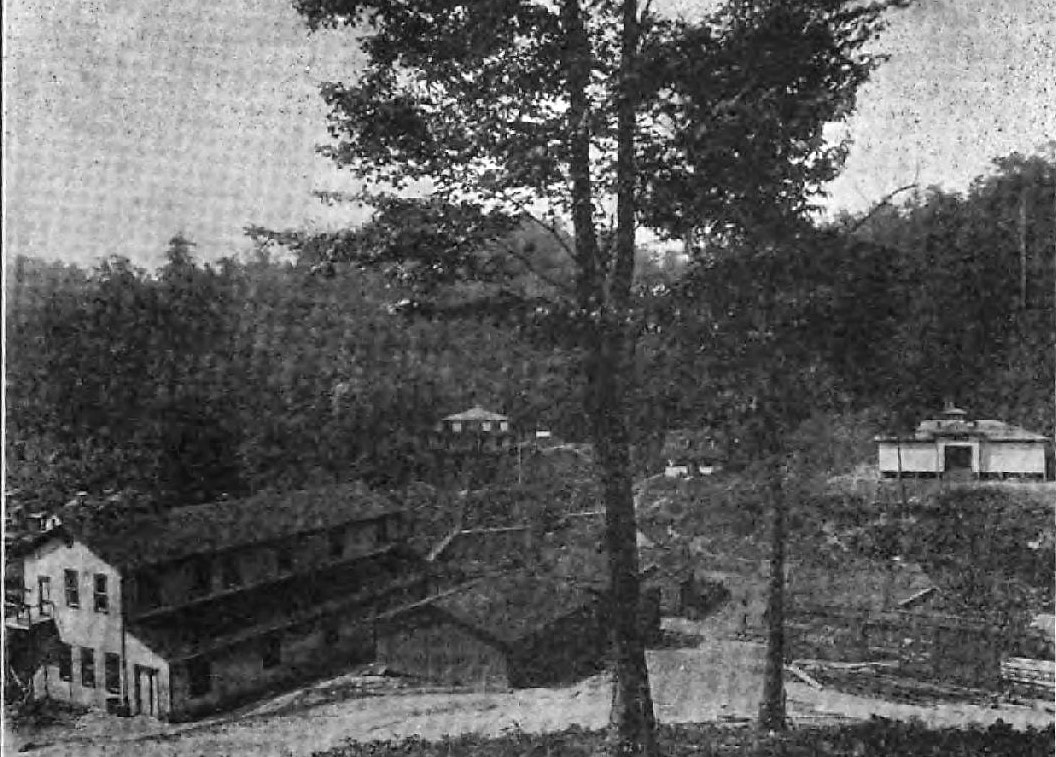

The home office of the Blue Creek Coal and Land Company at Blakely in 1919. Also pictured is the commissary, superintendent house, school house, and club house. Image from The Black Diamond

|

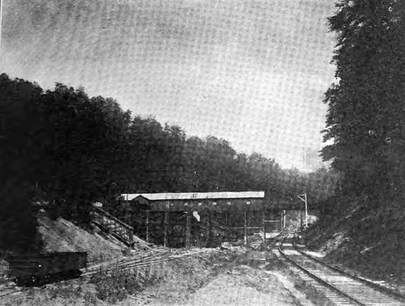

Double tipple serving the Blue Creek Coal and Land Company mines #4 and #5. Four tracks are beneath the tipple which provided five sizes of coal. Image from The Black Diamond

|

During the early 1900s, the Blue Creek Coal and Land Company owned large acreage in this area that was developed for mining. The company operated two mines at Blakely and another nearby at Wills Hollow. Another operator with interests near Blakely was the Strange-Elliott Coal Company with a mine at Hitop.

With the passing of years, coal mining operations began to dwindle, train frequencies decreased, and by the end of the New York Central era, Union Carbide mining activity was primarily concentrated at Hitop and Sanderson. Early into the Penn Central, activity at Hitop had ceased by 1971 leaving only the Sanderson region as the major load out. This remained in effect during the metamorphosis into Conrail by the late 1970s and continued for another decade. By 1990, all shipments by rail had ceased and the railroad has rusted ever since.

With the passing of years, coal mining operations began to dwindle, train frequencies decreased, and by the end of the New York Central era, Union Carbide mining activity was primarily concentrated at Hitop and Sanderson. Early into the Penn Central, activity at Hitop had ceased by 1971 leaving only the Sanderson region as the major load out. This remained in effect during the metamorphosis into Conrail by the late 1970s and continued for another decade. By 1990, all shipments by rail had ceased and the railroad has rusted ever since.

Twilight at Hitop. This image was taken of the tipple during its last full year of operation in 1970 but the scene already bespeaks of inactivity. When this operation was closed, the uppermost six miles of track was subsequently abandoned along Middle Pond Fork to Hitop. Image Jerry Taylor/courtesy Indiana University Press. All rights reserved

A flurry of speculation burst onto the scene during 2010

when plans were announced about renewed mining and shipment by rail. The

proposed name of this line, the Charleston, Blue Creek, and Sanderson, was to

incorporate the former B&O from Charleston to Blue Creek and henceforth from

that point to Sanderson over the former K&WV. For various reasons, however,

these plans have been forestalled with no news concerning a reactivation for a

few years as of the time of this writing. Realistically, the majority of track

is still intact throughout the route but it is in dilapidated condition and

would require extensive rebuilding in addition to almost thirty bridges. Five

years hence, the political and environmental climate is unfavorable not to

mention the shifting from coal to gas as an energy source. All circumstances

considered, the future reconstruction of this railroad is dubious at best.

Credits

"A Sampling of Penn Central"--Jerry Taylor--Indiana University Press

http://www.iupress.indiana.edu/product_info.php?products_id=19948

http://www.iupress.indiana.edu/product_info.php?products_id=19948

The Black Diamond

Richard J. Cook/Allen County Museum

Jeanie Droddy/Herb Wheeler collection

Earl Fridley

Kanawha County Public Library

Mark Layton

Library of Congress

Harry Lynn

Brad Mills

Carlos Morris

Jeffrey Morris

mywvhome.com

Lewis Gay Pauley

Curtis Riffle

Michael Ross

Mike Thomas

West Virginia Geological Surveys

West Virginia Oil and Gas Museum