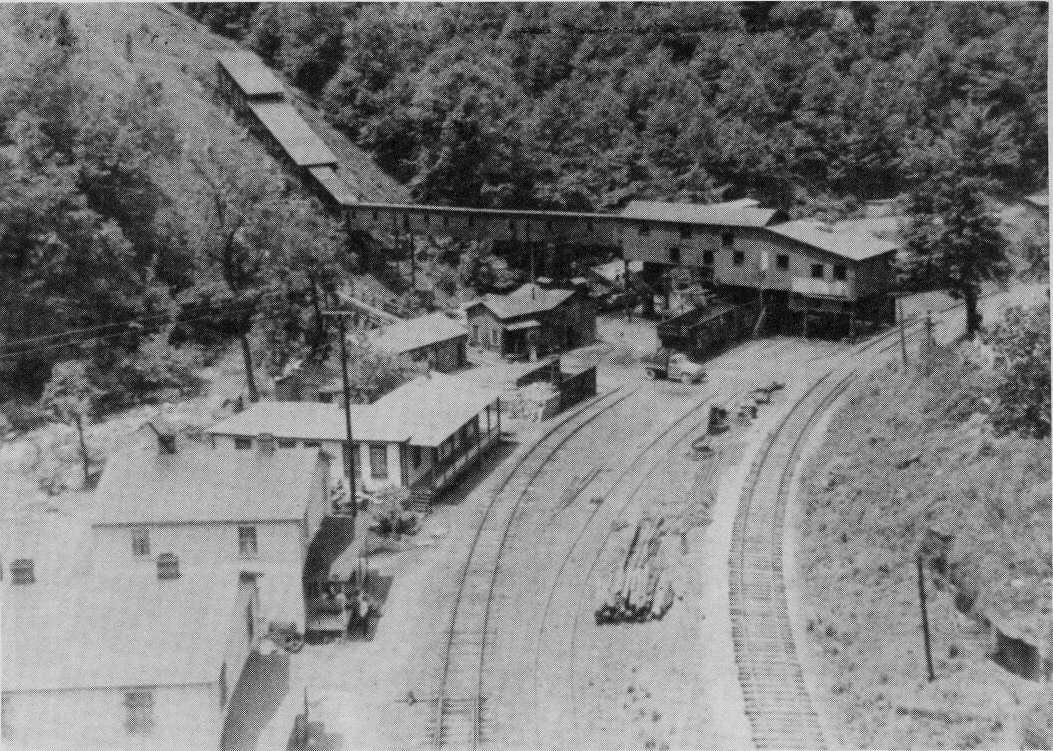

Spirits linger in those Appalachian mountain mists of mining and railroading since passed. Dream weave back to the 1970s when C&O/Chessie System trains echoed throughout the Paint Creek valley and one might have seen renowned C&O photographer Gene Huddleston trackside. A rainy day train passing beneath the West Virginia Turnpike at Milburn, WV. Image courtesy C&O Historical Society

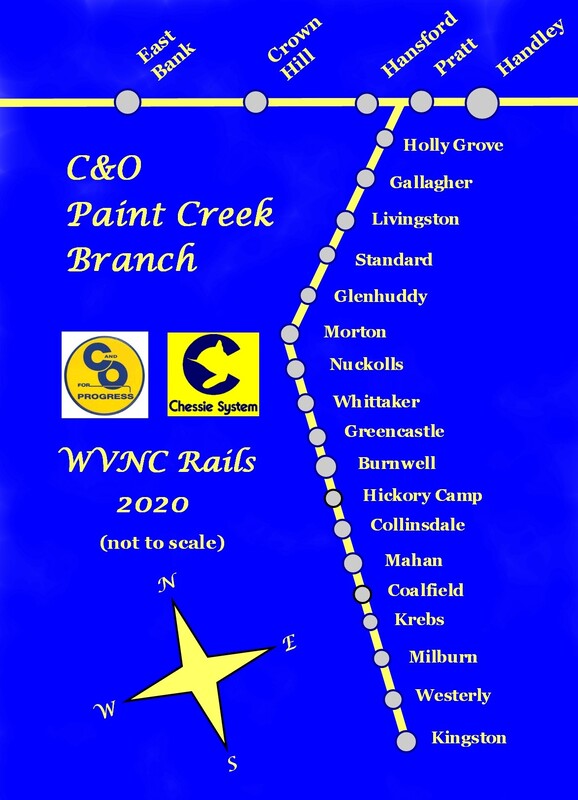

C&O Paint Creek Branch

The research of the railroad history of Paint Creek is at its root, a timeline of the rise and decline of the coal industry in the Appalachian region. It is also a microcosm of the ebbs and flows often marked by turbulence in the form of violence as a reaction to the early oppression of an industrial workforce. For a century the riches wrought forth from the black diamonds that fueled the economic engine of a nation cloaked many a dark secret. That Paint Creek was not spared is a thoroughly documented fact in unionized labor and railroad annals; in reality, it was an epicenter of the strife that exemplified the conditions. For as the waters of Paint Creek traversed the counties of Fayette and Kanawha destined for the Great Kanawha River, they were also mingled with the tears and blood of a distressed past.

From a personal perspective, I knew not of this unsettled past as a teenager on trips through the area with my father during the 1970s. Certainly not on the level of a thorough comprehension. These were often summertime forays along Paint Creek as my father fulfilled his work duties as a right of way maintenance engineer with Appalachian Power Company. My young interests were focused on the railroad, the mine tipples, and the creek itself nestled in a narrow valley humming with the sound of traffic on the Turnpike but otherwise tranquil. Years later, the association with the railroad was more distant only as a traveler on the Turnpike commuting between West Virginia and North Carolina. Seeing trains on the Paint Creek branch was occasional during the 1970s--the last one I would ever witness was in 1987 during my moving transition from West Virginia to North Carolina. Few photos of this branch line graced my collection but as alluded to on previous web site entries, these were among a group that were destroyed. It is also a personal regret that I did not photograph the railroad once traffic ceased followed by the subsequent track removal during the mid-1990s.

|

Paint Creek is a unique stream for a couple of notable reasons. First, it is among the smaller fraternity of free-flowing streams with a course in a south to north direction. Its 42 mile trek begins with its headwaters in Raleigh County then passing through Fayette and Kanawha Counties to its confluence with the Kanawha River at Pratt. For almost its entire course, Paint Creek is or was paralleled by railroad but for a brief sector between Kingston and Mossy. In addition to the C&O branch, the former Virginian Railway (present day Kanawha River Railroad) touches the upper reaches of the creek in the Mossy/ Pax region.

For many years during the halcyon period of active coal mining, Paint Creek suffered from the abundance of mining that occurred in its drainage basin. The stream ran dark and red acid run-off further choked its waters in an era devoid of anti-pollution regulations. It has been the absence of mining activity---as well as increased environmental awareness---that substantially improved its water quality. Today, the creek receives scheduled fish stockings and has reincarnated into a respectable trout fishery. |

Paint CreekIts journey through three counties complete, Paint Creek meets the Kanawha River in the scene above. At the confluence, Paint Creek serves as the natural boundary separating the communities of Hansford (left bank) and Pratt (right bank) The stream received its name from Indians who marked trees along its banks with natural paint. Dan Robie 2019

|

Condensed History---Rails Along Troubled Water

The development of a railroad on Paint Creek in the great Kanawha-Coal River Coal Field mirrored that of the Winifrede Railroad built several miles to the west from the Kanawha River. In fact, the same entrepreneur, Ralph Swinburn, was responsible for both. Predating both the Civil War and the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway, the Paint Creek Coal and Iron-Mining Manufacturing Company constructed a 5-foot gauge line of wooden rails and scrap iron spikes in 1853-1854. A locomotive built by the Tredegar Iron Works of Richmond was purchased for the railroad but proved too heavy and wide to operate on the trestles. The railroad reverted to the use of mule teams to pull the coal from Paint Creek to the Kanawha River at Dego (Pratt). After seven years of operating, the line was abandoned and no doubt hastened by the clouds of civil war. Ambitions were renewed on April 28, 1884 with the formation of the Kanawha and Paint Creek Railroad and its immediate successor, the Kanawha and Paint Creek Railway Company. Physical construction consisted of the development of a short section of right of way but no track was ever laid; in reality, the K & PCRC would remain in existence only as a paper railroad. It would not be until the onset of the 20th century that a railroad would parallel Paint Creek again.

Narrow gauge railroads (typically 3 foot gauge) were often the forbearer of a line that later witnessed further expansion and a conversion to standard gauge. The railroad that ultimately meandered along the banks of Paint Creek was no exception and from its humble beginning developed into a lucrative coal hauling branch of the C&O Railway for nearly a century.

Incorporated in 1898 as the Kanawha and Pocahontas Railroad, its inception was the brainchild of the Charles Pratt Company which owned vast holdings in the Paint Creek watershed. High quality bituminous coal veins were contained in this property extending to Keeferton (Westerly) as well as throughout the region as a whole. With the construction of the railroad in 1902, the mined coal had a transportation outlet to connect with the C&O main line and markets afar. The Kanawha and Pocahontas Railroad operated as a sole entity for only two years; in 1904, the railroad was leased to the C&O which operated it under that agreement until purchasing the line outright in 1914. During the ten year period from lease to ownership, C&O converted the railroad from narrow to standard gauge while extending the line to Kingston in 1911. Perhaps the line existed briefly as dual gauge until the conversion was complete. But once the railroad was completed in its entirety (21 miles), coal mines sprang up along its route to tap the mountains rich with black diamonds and with them, the emergence of camps and small towns.

|

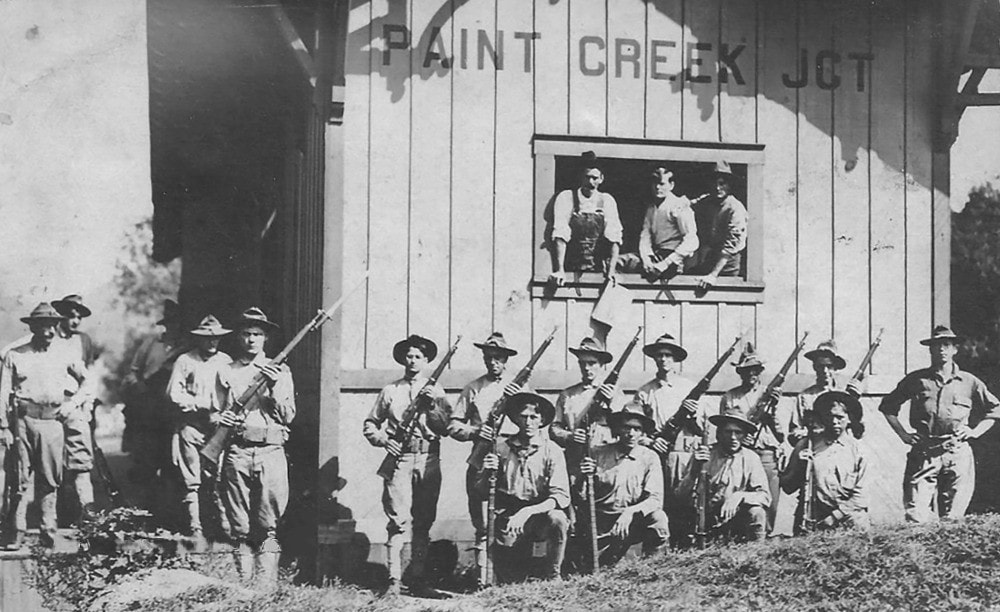

A group of armed mine guards congregate along the railroad on Paint Creek. Violent were the times in a tragic battle of greed versus civil indignities. Image Kanawha County Public Library

|

Beneath the façade of a glorious industrial past whereby West Virginia coal fueled the furnaces of a gargantuan steel industry and generated electric power, lay an indignity of human tragedy. The plight of the early era coal miner is well known to their descendants in West Virginia (and Appalachia as a whole) but beyond the borders it is oblivious to those who merely grasp at stereotypes. Theirs is a story of employer deceit, indifference to working and living conditions, and unabated abuses of authority by wage control. In essence, it is an account of ruthless coal barons with politicians in their hip pockets earning exorbitant profits from a workforce immersed in tyranny. Against this backdrop, insert the hostilities that erupted at Paint and Cabin Creeks during 1912 and 1913 in a battle for civil liberties.

|

1912-1913 Mine War

Published works are available which comprehensively describe the early labor history of coal mining in Appalachia for the reader with a thirst for detail. It is an epic topic with a broad range touching upon unionized labor and evolving legislation drafted to protect worker rights that exceeds the scope of this page; however, a summary of the events that transpired on Paint Creek is not out of context for it is also the history of the C&O Railway in the region.

|

The fight to unionize the coal mines of Kanawha County was not a new concept in 1912--the movement had its origins in the late 19th century. But by April 1912, there was sufficient force for mass protest as 7500 miners representing 100 mines on Paint and Cabin Creeks---the last non-union exceptions-- went on strike. Their demands were as follows (1) abolish blacklisting (discrimination) (2) allow unionization (3) abolish cribbing (as in mine construction) (4) installation of scales at mines (for accurate--and honest--weight of mined coal) (5) elimination of compulsory trading at company stores (the requirement of miners to spend their wages for company owned products/services) (6) determination of docking penalties by two check-weighmen-- one whom would be employed by the miners and (7) an increase in wages and with cash. (no scrip or credit cards). All of these demands were refused which exacerbated tensions. Coal operators retaliated by hiring Baldwin-Felts detectives to break the strike. Among the first actions by these men was to evict miners and their families from their company owned homes. Labor in the mines was replaced by scab (non-union) workers which included a large infusion of immigrants. A subsequent inquiry was conducted by the West Virginia Legislature of which implicated abuse by the coal operators but no action was taken. Anticipating hostilities with the striking miners, the coal operators constructed pillboxes for machine guns and other fortifications.

|

National Guardsmen pose at the Paint Creek Junction during the height of the Paint Creek mine war. Image West Virginia and Regional History

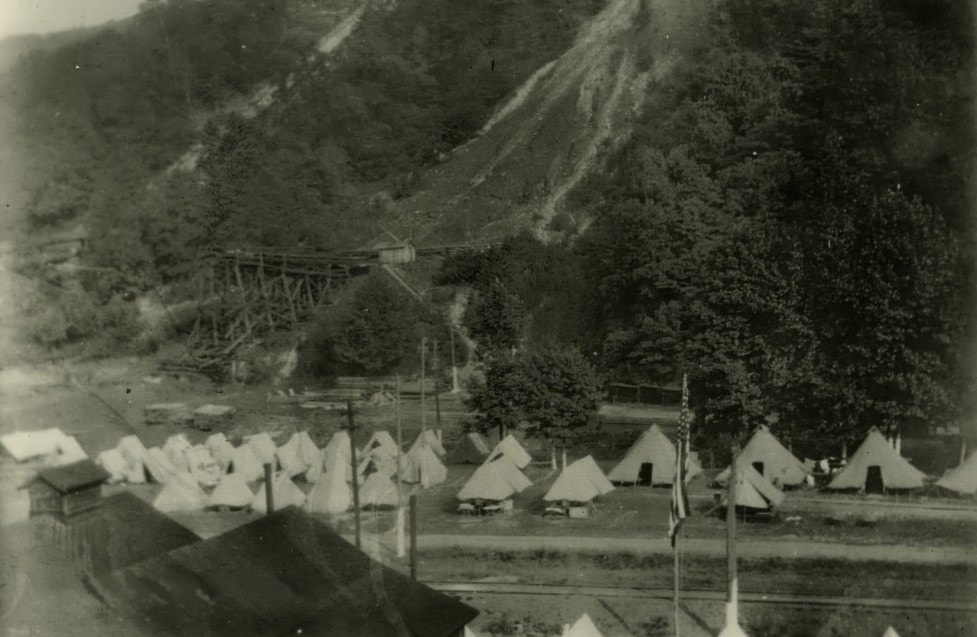

Militia encampment on Paint Creek possibly near Hollygrove. Image Kanawha County Public Library

|

|

Painting of Mary "Mother" Jones (1837-1930) who was a central figure during the 1912-1913 mine wars. Her voice lent support during the formative years of organizing unionized labor in America. Image West Virginia and Regional History

|

The C&O Railway was mired in a conundrum. Its revenue came from the coal operators but the miners were their brethren--brothers in arms, so to speak. It stood to suffer damage inflicted by either party in a war and certainly its employees were in harm's way. Mary Harris, aka "Mother Jones", the leading voice during the formative years of unionization, advocated armed aggression against the mine guards and vehemently denounced West Virginia governor William Glasscock who, in reality, satisfied neither side. "Mother Jones" spoke to gatherings in Charleston at the state capitol outlining the plight of the miners and at a later speech at the court house --noting the C&O Railway-- asked of the miners, "I want you to guard the C&O tracks and trains everywhere. The young men on the C&O are our men, and they are working to help us, and I want you to protect their lives. Don't meddle with the track and if you catch sight of a Baldwin blood-hound, put a bullet through his rotten carcass". But in spite of speeches and pleas, the lack of legislative action by the state sowed the seeds for armed conflict. These were dark times in the history of American labor that climaxed in the spilling of blood.

|

|

The inevitable skirmishes began with the killing of mine guards throughout the watersheds of both Paint and Cabin Creeks. A major battle erupted at Mucklow (Gallagher) resulting in the deaths of sixteen miners and guards. By September 1912, other union miners from the area joined the striking miners. In response, 6000 armed men converged in the area as Governor Glasscock called in a 1200 man militia while declaring martial law. Both the mine guards and miners were ordered to disarm and military courts were established. Miners were forbidden to congregate in large numbers--at this time, Mother Jones reappeared and was arrested for allegedly reading the Declaration of Independence to the striking miners. Martial law was suspended on October 5 but was soon reinstated in November as scab workers and C&O trains had been fired upon. Many miners were jailed and military courts re-established until martial law was again lifted in January 1913. During the conflict, the town of Pratt transformed into a military encampment with the presence of militia, mine guards, and the internment of striking miners.

|

Union leader "Mother Jones" spoke at the 1885 state capitol during the 1912 escalation on Paint Creek. Ironically, this stately structure burned on January 3, 1921 with stored ammunition from the Paint Creek and later conflicts exploding in the inferno. Image West Virginia and Regional History

|

Perhaps the most notorious event during the Paint Creek mine war was the passage of the "Bull Moose Special"--an armored train equipped by the coal operators with machine guns. As the train passed a miner tent city, the inhabitants were fired upon with one miner killed and several others wounded. A third martial law was imposed and military courts reconvened. Yet again, Mother Jones was arrested and given a 20 year sentence. Ultimately, it was the inauguration of a new West Virginia governor that resolved the conflict. After taking the oath of office, Governor Henry D. Hatfield immediately traveled to the strike area. He quickly ordered civil rights restored to the miners, abolished the military courts, and commuted Mother Jones sentence. Governor Hatfield imposed peace to both combatants in the conflict thereby ending the struggle on Paint and Cabin Creeks.

Post Mine War History

The mine war era is the high water mark in the history of Paint Creek--in a notorious context--but from the tragic standpoint inked in blood, quite a significant one. It was the vanguard for the need of labor reform that would continue in a violent tone for another decade in an industry that was inherently dangerous demanding fair treatment of its workforce. By the 1920s, the unions--notably the United Mine Workers--had obtained sufficient force as well as achieving influence as a political lobby to improve working conditions in the coal industry considerably. But the battle to further improve the industry in all facets would continue for decades.

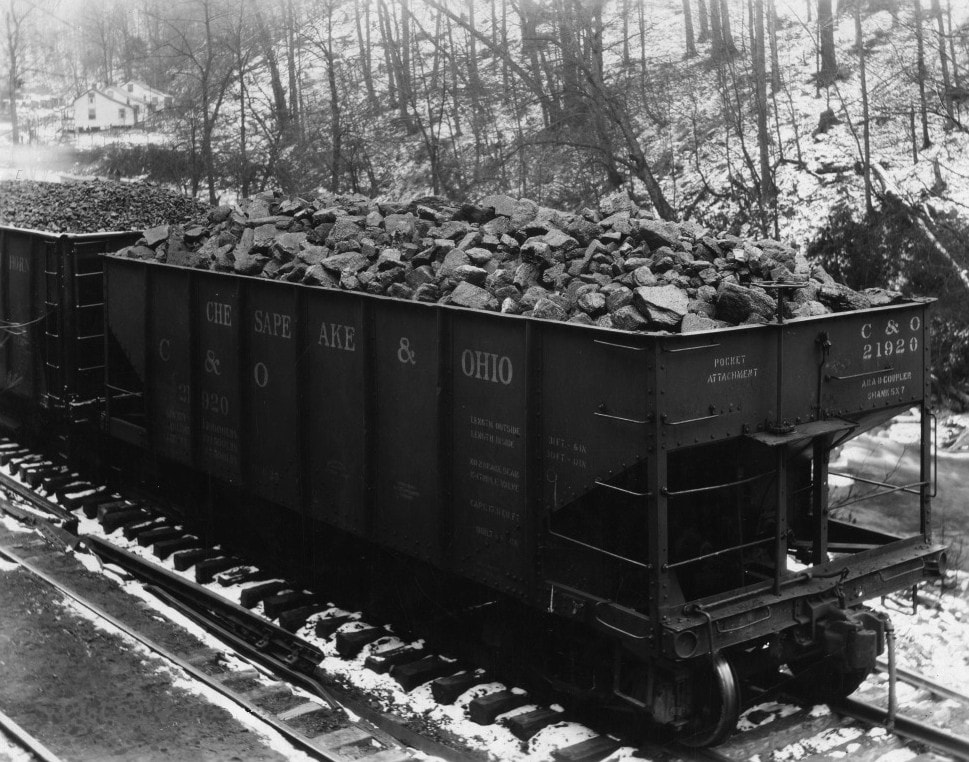

As to the disposition of the C&O Railway on Paint Creek, its fortunes were directly intertwined with those of the coal industry. Periods of prosperity fluctuated with downturns that affected traffic volumes on the railroad throughout its history. External factors such as occasional labor strikes, the Great Depression, and the great demand for coal during the World War II years directly impacted operations. Even Mother Nature would step in and take center stage in a destructive fury. Creek valleys in Appalachia are easily susceptible to flash flooding and with prolonged rainfall, the threat of major flooding. Because most of these valleys are narrow, a flooding stream can destroy all in its raging path. In July 1932, Paint Creek took its turn in one the worst floods in West Virginia history. On July 11, a cloudburst dumped multiple inches of rain swelling the creek immediately unleashing a devastating force. In a region already mired in the depths of the Depression, Paint Creek transformed into a rampaging stream demolishing all in its path. Homes were destroyed and at least eighteen lives were lost in the disaster. The C&O track and roadbed was washed away in addition to railcars and lineside structures requiring a complete rebuild of the railroad. In one respect the Paint Creek watershed never recovered--it lost population and an established infrastructure.

|

In the aftermath of the 1932 flood, the coal industry slowly recovered but had already been in a subdued Depression era economy. But the tempo increased during the war years of the 1940s with the demand for coal to produce the American war machine. Mining remained strong through the 1950s and 1960s but by the 1970s, decline had become apparent. Smaller mines had closed and the coal towns were fading from the map. As a result, the volume of coal mined and number of trains decreased proportionately.

Coal was the lifeblood of Paint Creek for nearly a century. It was also the backbone of revenue for the C&O Railway during its storied history.

|

Prior to the World War II years, the Paint Creek watershed was effectively landlocked by a poor transportation system. Twisting narrow roads made travel to the Kanawha Valley or the Beckley region an arduous ordeal. The railroad was the most feasible means of travel until passenger service was discontinued in 1949. By this time, the construction of the West Virginia Turnpike was in the works and when completed in 1954, substantially improved automobile and truck travel. The construction of the highway--although necessary--altered or removed forever a substantial amount of early mining history along the Paint Creek. Lost as a victim of progress.

The decade of the 1980s proved the swan song for the railroad along Paint Creek. Still the C&O--as one of three railroads in the Chessie System formed during 1972---the line remained active to serve the sole mining activity in the Milburn area. Trains now operated sporadically passing through the ghost camps of mines long since vanished. Eventually, all mining served by rail on Paint Creek ceased and in January 1988, the final trains operated on the line surviving into the early CSX era. The railroad lay dormant into the 1990s until CSX decided to remove the track at mid-decade. Ironically, new mining opened at Kingston during this period but the railroad no longer existed to serve it. Abandoned in its entirety, the C&O Paint Creek Branch (technically classed as a "Sub") now exists only in the confines of history and inclusion into the 44 mile long Paint Creek Rail Trail.

Operations and Assorted

The frequency of movements on the Paint Creek line was greater in the earlier years--specifically the pre-World War II era--simply because the number of active mines was greater in quantity. Schedules were determined by volume of shipped coal and the replenishment of empty cars. Since the needs would vary on a daily basis per any respective coal operator this would necessitate trains virtually every day. Until 1949, another factor to consider was passenger service. In later years perhaps beginning with the early 1960s, trains were dispatched on an as needed basis as the number of active mines shipping had decreased.

|

Motive power used by the C&O on the line during the steam era utilized various types throughout the years. Certainly the 2-8-0 Consolidation was common in early years and in the later years, the huge Class H-6 2-6-6-2 could be seen negotiating the curves along the Paint Creek drainage. Passenger power ranged from 4-4-2 Atlantics to the 2-8-0 by the end of the steam era. The diesel era--dating from its introduction to the end of service on the line--was the domain of the EMD GP7 and GP9 models.

C&O GP9 #6142 and its sisters were staple power on the Paint Creek line throughout their careers. Image courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

Similar to the majority of coal hauling branch lines in Appalachia, gravity was favorable for the movement of trains on the C&O Paint Creek line. Empties traversed upgrade while the loads mercifully moved on a descending gradient. Listed below are the elevations above sea level for selected communities/coal camps along Paint Creek:

|

Pratt---633

|

Burnwell---883

|

|

Hollygrove---650

|

Collinsdale---892

|

|

Gallagher---646

Livingston---666

Standard---686

Whittaker---807

Greencastle---850

|

Mahan---945

Coalfield---1001

Milburn---1135

Westerly---1210

Kingston---1467

|

Handley-Pratt-Hollygrove

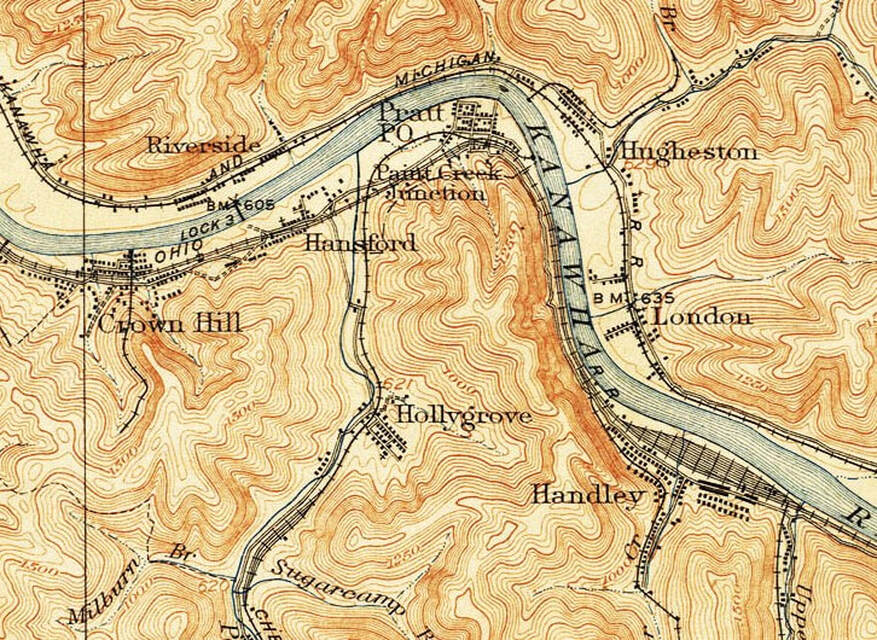

A 1908 topo map of the region that includes the immediate Kanawha River valley, the Paint Creek branch and junction, and the large Handley Yard along the C&O main line. Of interest during the early years was that the Paint Creek branch crossed the C&O main at Paint Creek Junction thereby passing through the town of Pratt and connecting with the latter at the east end of town. Note the rail branches along many of the Kanawha River tributaries including Handley and Crown Hill and also the scale tracks on Paint Creek south of Hollygrove.

Handley

An eastbound coal train is passing the west end yard leads as it arrives at Handley in this circa 1948 photo. Coal was king on the C&O and powerful locomotives such as Class K-4 2-8-4 #2705 ably served this kingdom. Coined as a "Berkshire" type locomotive by most roads, the C&O dubbed this class as "Kanawha"---named for the river visible in this photo. Image courtesy C&O Historical Society

Situated along the Kanawha River between Pratt and Montgomery, the importance of the yard and facilities at Handley cannot be understated. The location was a division point boundary for the New and Kanawha River subdivisions on the C&O main line (a jurisdiction border that remained into the CSX era). In the context of this page, its major purpose was that of a marshalling yard for C&O staging on the coal rich Paint and Cabin Creek branches. Outbound empties were assembled into trains for distribution to the mines located on both creek drainages and, conversely, loads returned for classification into trains for furtherance on the C&O main line.

It is August 1955 at Handley with steam and diesels co-existing on the C&O as evidenced by the F3s on the road train. In the foreground is H-6 2-6-6-2 #1515 and caboose assigned as the Paint Creek switcher. Photo courtesy C&O Historical Society

Like the other mining communities served by the railroad, Handley itself was established as a coal mining center. Established by the Wyoming Manufacturing Company, the Kanawha coal seam was first opened on Upper Creek and further mining was opened on the Lower Creek region by the Chesapeake Mining Company. The arrival of the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway in 1873 accelerated the development of additional coal mining in the region and the subsequent expansion by virtue of the means for transporting it. For several years, Handley was merely a flag stop until a depot was constructed in 1891. C&O had originally utilized a yard to the east at Montgomery but this was relocated to Handley during the 1890s. As a result, the location increased in prominence as a main line division point, servicing terminal, and marshalling yard for coal mined on the Paint and Cabin Creek branches.

|

This 1932 photo focuses on the construction of the London Lock and Dam on the Kanawha River but also provides a look at the Handley Yard (lower right) from the era. Across the river is the town of London and the New York Central Railroad. Image West Virginia and Regional History

|

A 2010 view that looks westbound at what remains of the railroad at Handley. All but one of the yard tracks are gone and the trees at right now occupy the expanse of the former terminal. The coal train was tied down on the main awaiting a re-crew. Dan Robie 2010

|

Until deep into the 20th century, Handley remained a focal point of operations on the C&O. Its apex was certainly during the steam era with its turntable, shops, and servicing facilities utilizing maximum personnel. During the twilight years of steam in the late 1950s, its importance remained intact as a new yard office was constructed to replace the previous depots. The conquest of steam by the diesel locomotives reduced the servicing facilities at Handley but the yard remained active. Ultimately, it was the decline of coal originating on Cabin and Paint Creeks and the advent of the unit coal train that would doom Handley by the 1990s. A visit to Handley today will reveal only the shell of its once mighty stature. The office still stands but is closed, the yard tracks are gone, and much of the former yard property is overgrown. CSX trains still pass through on the main line and coal trains are tied down here as needed for crew swaps but this, too, is in decline with the continued decrease in coal traffic.

Pratt

|

In a history spanning more than 150 years, Pratt has been known by other names beginning with Clifton upon its founding in 1851. This name remained in use until the years following the Civil War when it was renamed Dego in 1873. During the early years of the Industrial Revolution the region expanded with the development of the coal fields and one such firm that emerged during that prosperity was the Charles Pratt Coal Company in 1889. It owned substantial coal mining properties in the Paint Creek watershed and because of due influence, the name of the town by the Kanawha River was changed once again incorporating as Pratt in 1905.

|

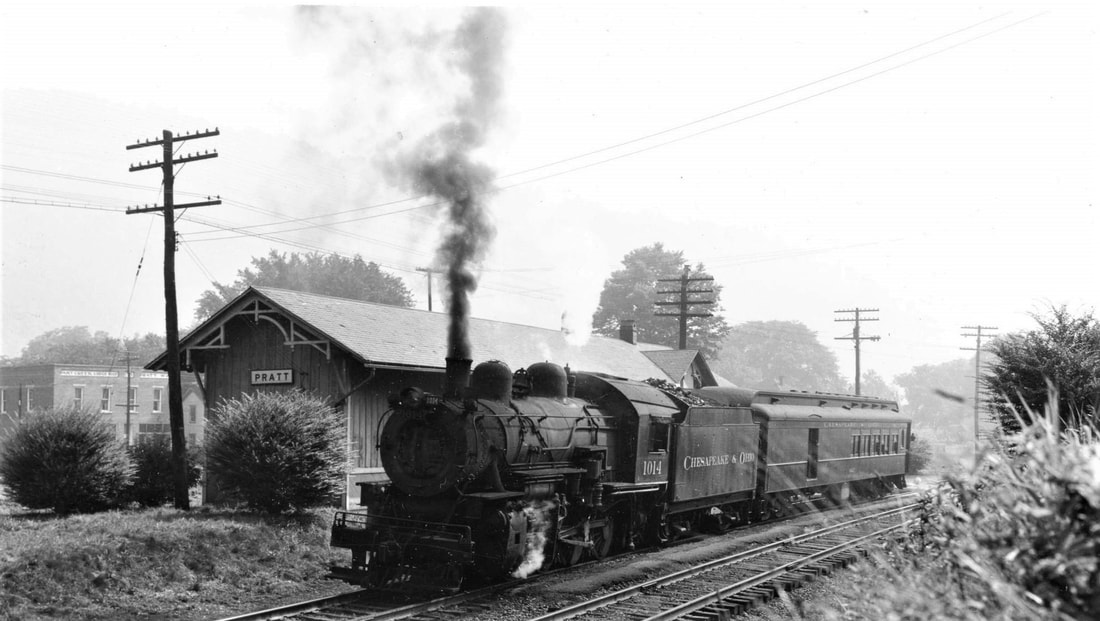

Train time at Pratt in 1946. Class G-9 2-8-0 departs with Train #170 (single coach) bound for Paint Creek. Image courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

Strategically located, Pratt was in an ideal position with regards to transportation. The Kanawha River lay at its north boundary and in 1873, a completed Chesapeake and Ohio Railway main line passed through providing not only freight access but passenger service as well. By the turn of the century, its railroad significance increased with the construction of a line along Paint Creek to tap the vast coal reserves. Pratt became the junction for this branch line and at a point west of town at the creek, the railroad name of Paint Creek Junction was born.

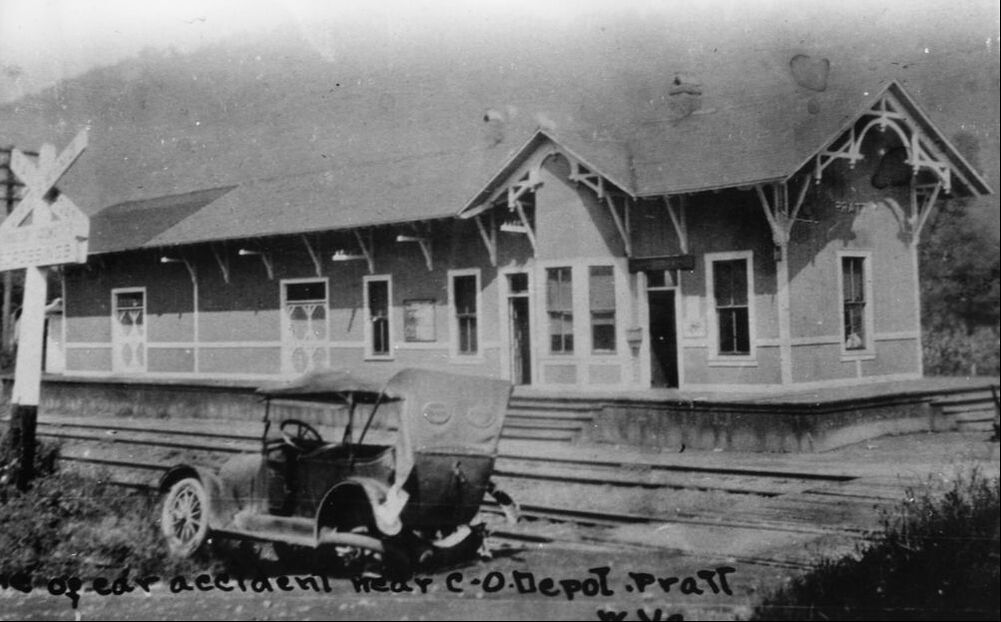

The C&O depot at Pratt as it appeared circa 1916. Note the addition of a freight section to the structure clearly defined by contrast of color on the roof. Image courtesy C&O Historical Society

During the 1912-1913 mine war on Paint Creek, Pratt became the focal point of the hostile tensions. Both the coal company mine guards and the West Virginia National Guard established the community as headquarters during the conflict. In addition, the military tribunals were conducted here as well as detainment for the striking miners held in what were referred to as “bullpens”. Mother Jones was also imprisoned here at a location known as Mrs. Carney’s Boarding House during the height of the uprising.

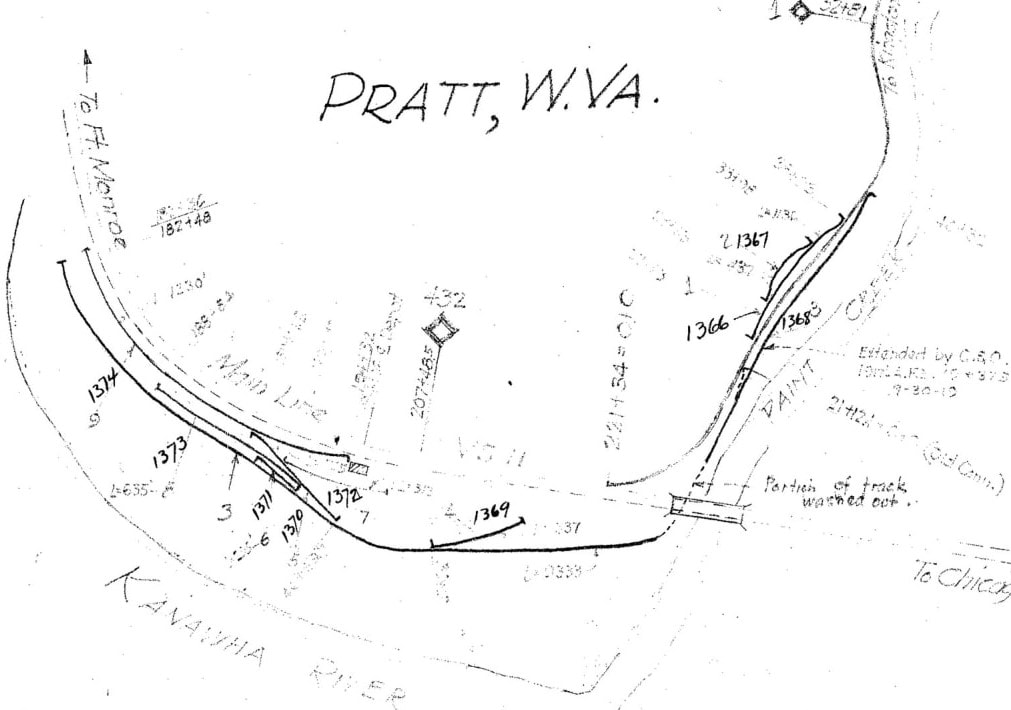

A 1937 C&O Railway track map of the layout at Pratt. The main line is dotted as the chart focuses on sidings and secondary tracks in town and on the Paint Creek line to Milepost 1. Note the industrial track passing beneath (and washed out) the main at Paint Creek Junction into Pratt used for storage, the depots, and shippers. The side tracks on Paint Creek served the H.M.J Coal Company with a 1919 modification. Perhaps for map clarity, no direct connection from the Paint Creek line to the C&O main is depicted. Map image courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

Eastbound view of the C&O (CSX) main line looking across Paint Creek toward Pratt from Hansford. On the opposite bank was the junction of the Paint Creek branch with the main line. Early in the 20th century the location was designated as Paint Creek Junction on maps but the name apparently was dropped in later years. Dan Robie 2019

|

If one visits Pratt today, the double track CSX main line signifies the railroad presence but buried deep in the annals of history is considerably more. During the heyday of coal mining in the Kanawha Valley as well inclusion of the Paint Creek line, the plant at Pratt was substantially more. Within the town center was located a service track that extended from the Paint Creek line to the main line at the east end of Pratt. Extending from this track were spurs that served the depot area and possibly for storage that remained intact at least into the 1950s. There appears to have been modifications to the plant at Pratt throughout the years and of note the vicinity of Paint Creek Junction. On the 1937 map above, there is mine trackage that served the H.M.J Coal Company. Also at this date the Paint Creek line passed beneath the C&O main line bridge spanning the creek although it is noted that a section was washed out. The final connection configuration was the curved track leading to the main although not showing as connected on the map.

|

Turn back the clock to 1962 and this was a frequent sight at Paint Creek Junction. A train of empty hoppers led by C&O GP9 #6108 and a sister are bound for the mines scattered in the Paint Creek basin. They are diverging from the C&O main line onto the Paint Creek Branch. And so shall we. Image courtesy C&O Historical Society

Hollygrove

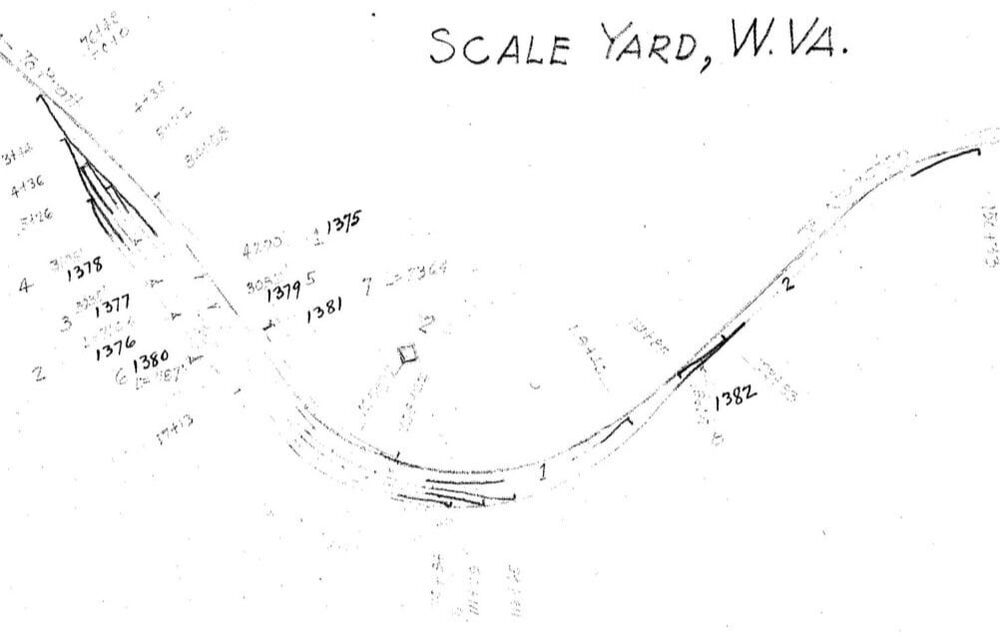

Hollygrove bore the distinction as the only community along the Paint Creek Branch that had no dedicated active coal mining. It was no less important, however, to the railroad for it was the site of a scale yard. Situated just to the south of Pratt, its location in a wide bottom (relatively speaking) proved suitable for the construction of multiple tracks for the weighing/storage of hoppers on the line.

|

During the 1912-13 strike, miners and their families were evicted from the company homes owned by the coal operators. As a result, miner tent colonies sprung up along Paint Creek and the railroad such as this one at Hollygrove. Image West Virginia and Regional History

|

Aerial view of the Hollygrove area notating the locations of the former C&O Railway scale yard and miner tent colony.

|

|

The multi-track scale yard at Hollygrove (Milepost 2) as it was during 1937. Loaded hoppers from the mines would be weighed here then assembled for furtherance to Handley. Map courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

Abandoned right of way looking north through Hollygrove. The miner encampments during the 1912-1913 war were not far from this location. Dan Robie 2020

|

During the 1912-1913 miners strike, Hollygrove was a flashpoint in the crisis if for no other reason than its proximity to Pratt. Displaced miners and their families lived in a tent colony here separated by only a few miles from the company guards and militia at Pratt. It was here on February 7, 1913 that the infamous armored "Bull Moose Special" train passed through opening fire on the camp resulting in the death of one miner while inflicting numerous injuries to others.

Gallagher to Standard

|

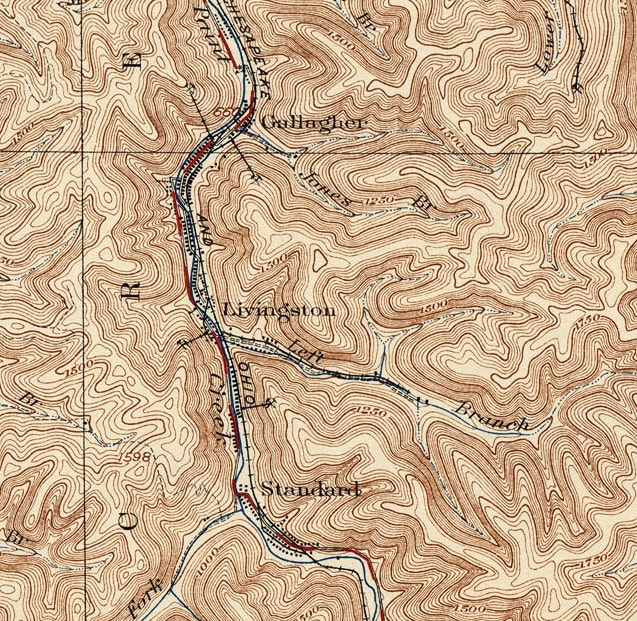

A 1928 topo map of the region extending from Hollygrove through Gallagher to the south end of Standard. From Pratt, the railroad paralleled the east bank of Paint Creek until crossing to the west bank for the first time at Standard. Of the entirety of the C&O Railway in the Paint Creek watershed, this area remains largely extant for it was untouched by the construction of the West Virginia Turnpike during the early 1950s. As a result, the former mining communities survived with the greatest population density even after the coal was exhausted, As with the majority of the route, the railroad right of way is clearly discernable.

|

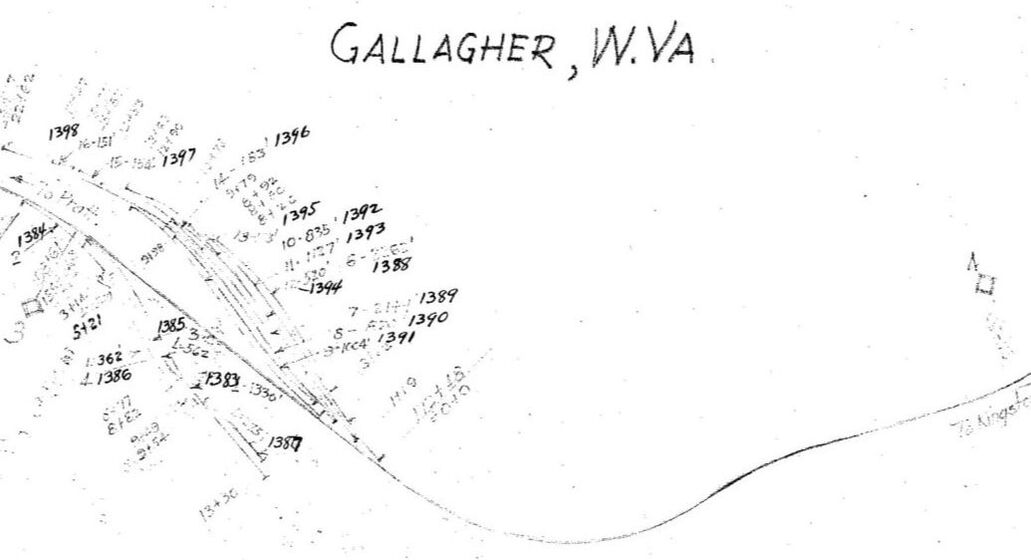

Gallagher (Mucklow)

As the first mining community along the Paint Creek line, Gallagher was also a notable one. First founded with the name of Mucklow, it was a coal producing camp for many years. In 1902, the Paint Creek Collieries opened the Paint Creek mine and by 1907, a second operation was online with the Scranton mine. A look at the C&O 1937 map below will reveal two mines still in operation--by this date the Paint Creek Coal Company-- with a substantial amount of trackage. In such a narrow valley, the layout was compact and especially considering the presence of mine tipples and company homes.

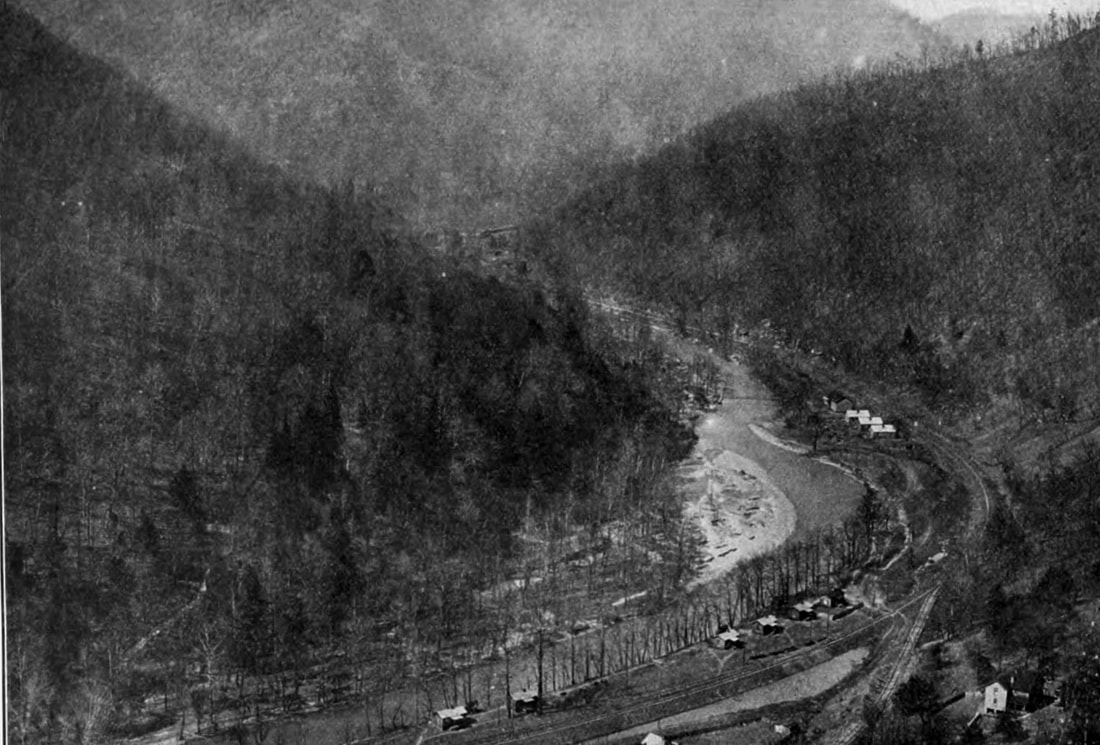

Mountain top view looking north through the Paint Creek valley at the mining town of Mucklow (Gallagher). The railroad is visible as is a spur diverging to a mine tipple below the vantage point of the photographer. This rare photograph was taken in the immediate years following the 1912 mine war--perhaps circa 1915. Image West Virginia Geological Surveys

Gallagher (Mucklow as it was called at the time) was within the epicenter of the 1912-1913 Mine War turbulence and sadly, violence. Striking miners opened fire on the company store as well as a company owned ambulance. The date for these acts must have been February 7, 1913 as it is recorded that later that evening, the Bull Moose Special train operated occupied by mine guards, militia, and railroad police attacked the tent colony at Hollygrove. Tensions remained high at Mucklow throughout the crisis because of its proximity to the antagonists and as the first mining camp on the route. The mine war ultimately subsided but two decades later--Gallagher as it was renamed--suffered severe damage during the 1932 Paint Creek flood.

Livingston (Wacomah)

Four miles from Paint Creek Junction on the route lay the mining camp of Livingston. Initially named Wacomah, the town name was changed by the Paint Creek Coal Company perhaps to remove the stain of the 1912-1913 Mine War. At its peak, there appears to have been two mines in operation extending into the 1930s.

|

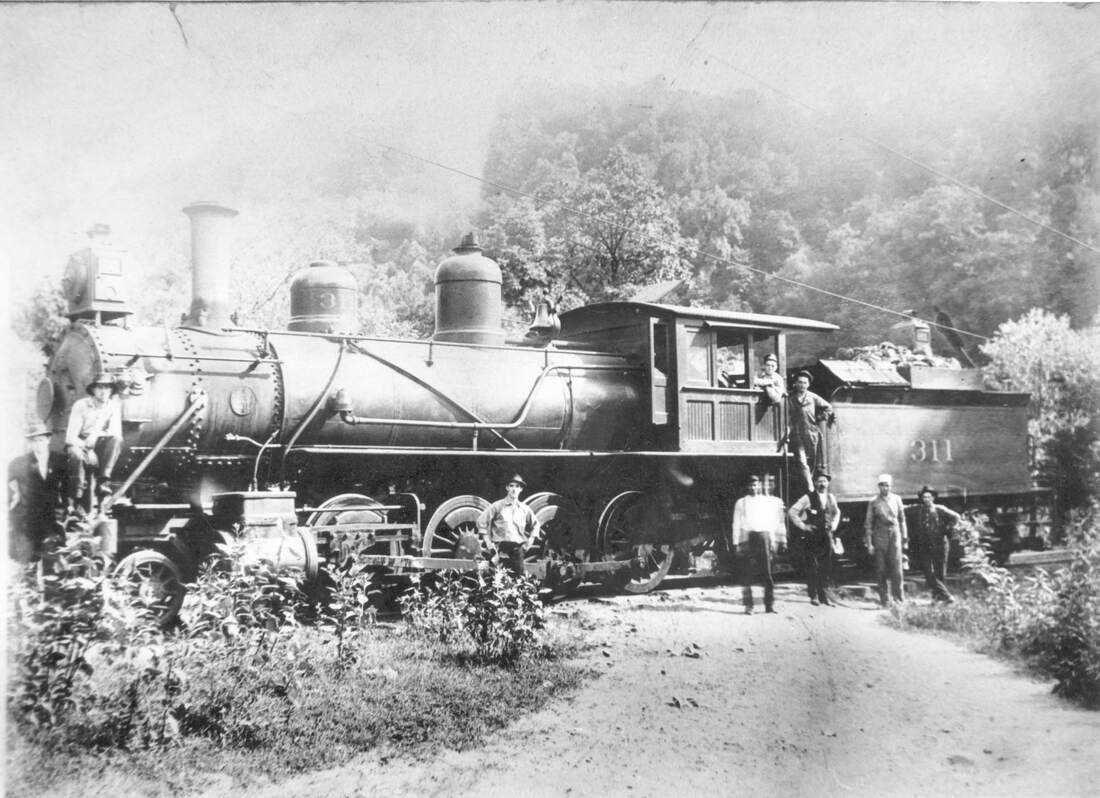

C&O 2-8-0 #311 and crew pose for the photographer during the early years of operation along the Paint Creek line. Location is unidentified but could possibly be at Livingston (Wacomah). Image courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

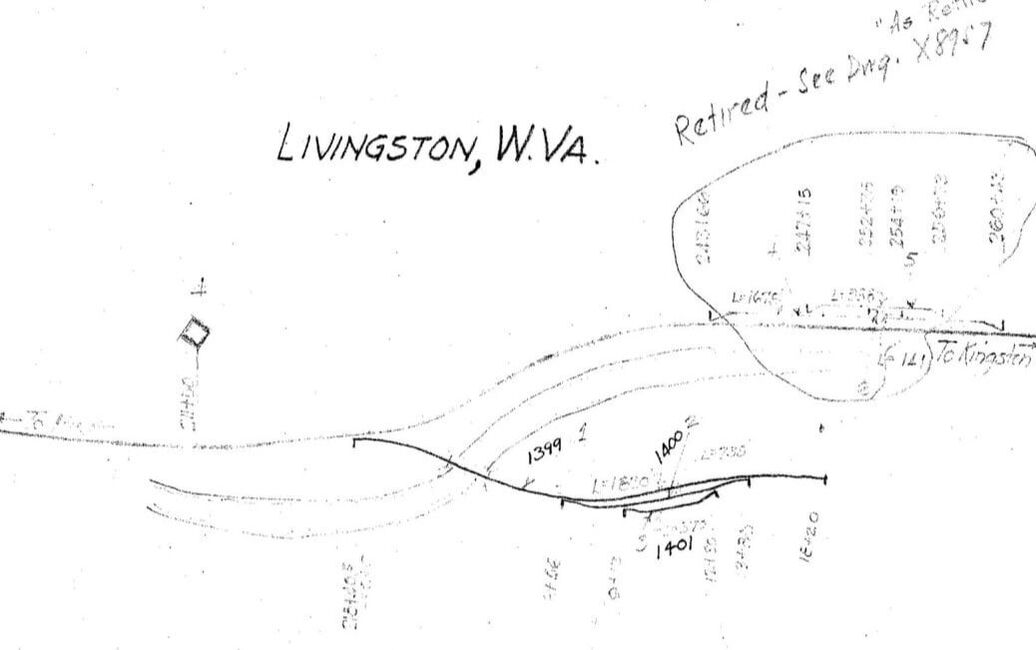

1937 C&O map at Livingston (Milepost 4) showing the spur that crossed the creek to serve the mine. The Wacomah Fuel Company is noted as the operator--this company assumed operation of the Paint Creek Coal Company mines at both Gallagher and Livingston during the 1930s. Map courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

Around 1930, the Wacomah Fuel Company assumed operation of the former Paint Creek Coal Company Mines located at Gallagher and Livingston. The tenure was brief as one mine was soon retired and the final one---located on a spur that crossed Paint Creek--had ceased by 1939.

A thought that occurred about the trifecta of Gallagher, Livingston, and Standard as to why they remained largely intact after the demise of coal is their proximity to the Kanawha Valley. Once the mines closed residents and their descendants were able to pursue other opportunities in the (then) industrial Upper Kanawha Valley in coal related industries, the railroad, and heavy manufacturing. Since the West Virginia Turnpike bypassed all three, its construction did not result in any loss of real estate. In fact, the completed Turnpike provided a direct link to employment in the Charleston area.

Standard

The third in a trio of mining camps along Paint Creek between the Kanawha River and the eventual West Virginia Turnpike, Standard appeared on the map in 1902 with the creation of the Standard Splint and Gas Coal Company. By the 1930s the Paint Creek Coal Company had a presence in the community with an office although with no apparent active mining.

|

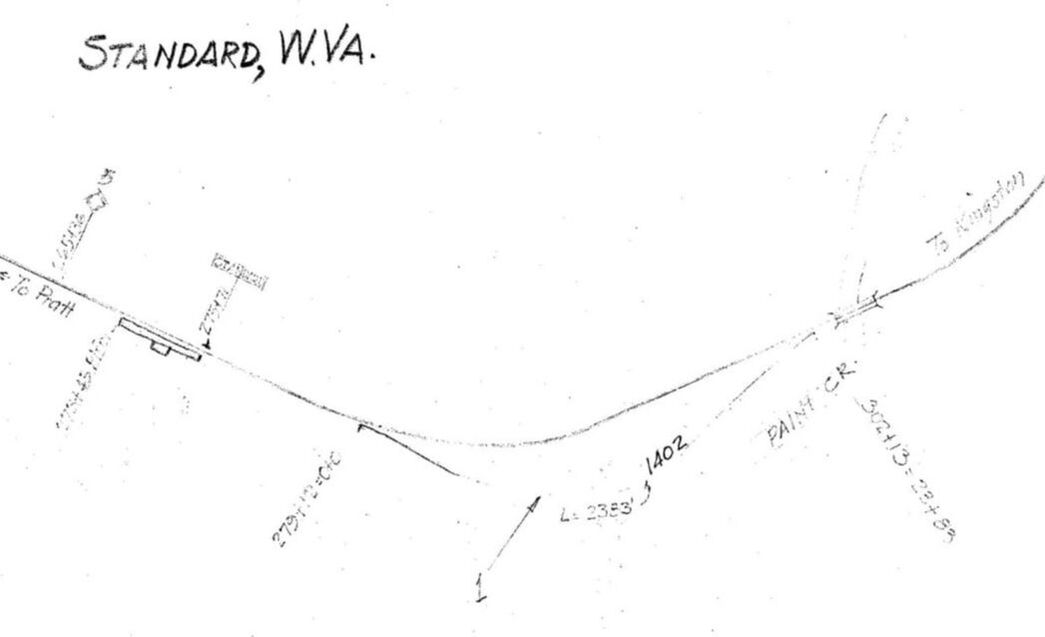

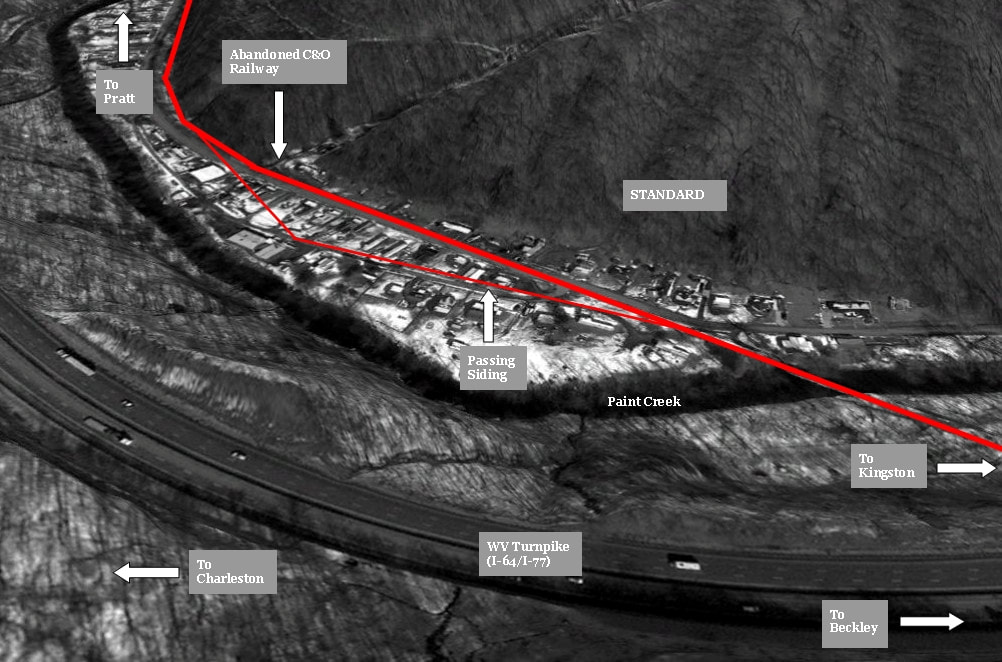

Standard (Milepost 5) was the location of a 2400 foot passing siding, the first one moving south on the line. This siding was unique because it passed through the town rather than directly parallel the main. Map Courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

The townspeople of Standard begin to assess the damage in the wake of receding water during the aftermath of the 1932 flash flood. This photograph preserves for posterity the scene by the railroad at the Paint Creek Coal Mining Company. Image courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

Standard...1962A glimpse of a bygone era as a rail worker with a velocipede has cleared the track for the passing train. Empty hoppers moving south for redistribution to the Paint Creek mines. Image courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

Standard...2018The same grade crossing at Standard 56 years later from a slightly different vantage point. Only memories remain from when C&O trains were daily fare here and throughout the Paint Creek basin. Dan Robie 2018

|

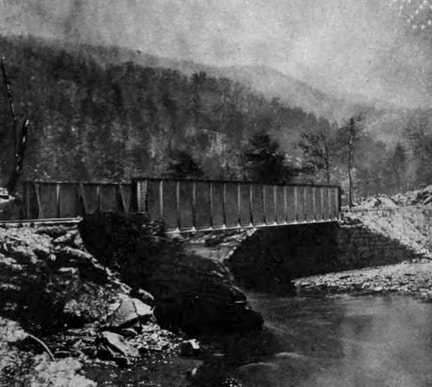

The first passing siding moving southbound on the Paint Creek line was located at Standard. Located on a curve, this 2400 foot siding diverged from the main and passed through the former business district instead of paralleling the main in typical practice. In the 1962 photo above, the south switch is visible beneath the caboose indicating it was still in existence at that date. Another first at Standard was the crossing of Paint Creek by the railroad moving from the east to west bank of the stream. This crossing and later ones southbound on the route utilized the girder plate type bridge.

|

Aerial view marking the C&O trackage at Standard as it was superimposed in contemporary times. The offset passing siding was the notable feature and it is here that the West Virginia Turnpike begins its parallel of the route south.

|

This girder plate bridge at Standard marked the first of what would be several crossings by the C&O over Paint Creek. The dilapidated condition of the wood planking magnifies the passing of 32 years since the last train crossed on the return to Pratt. Dan Robie 2018

|

Glenhuddy to Burnwell

|

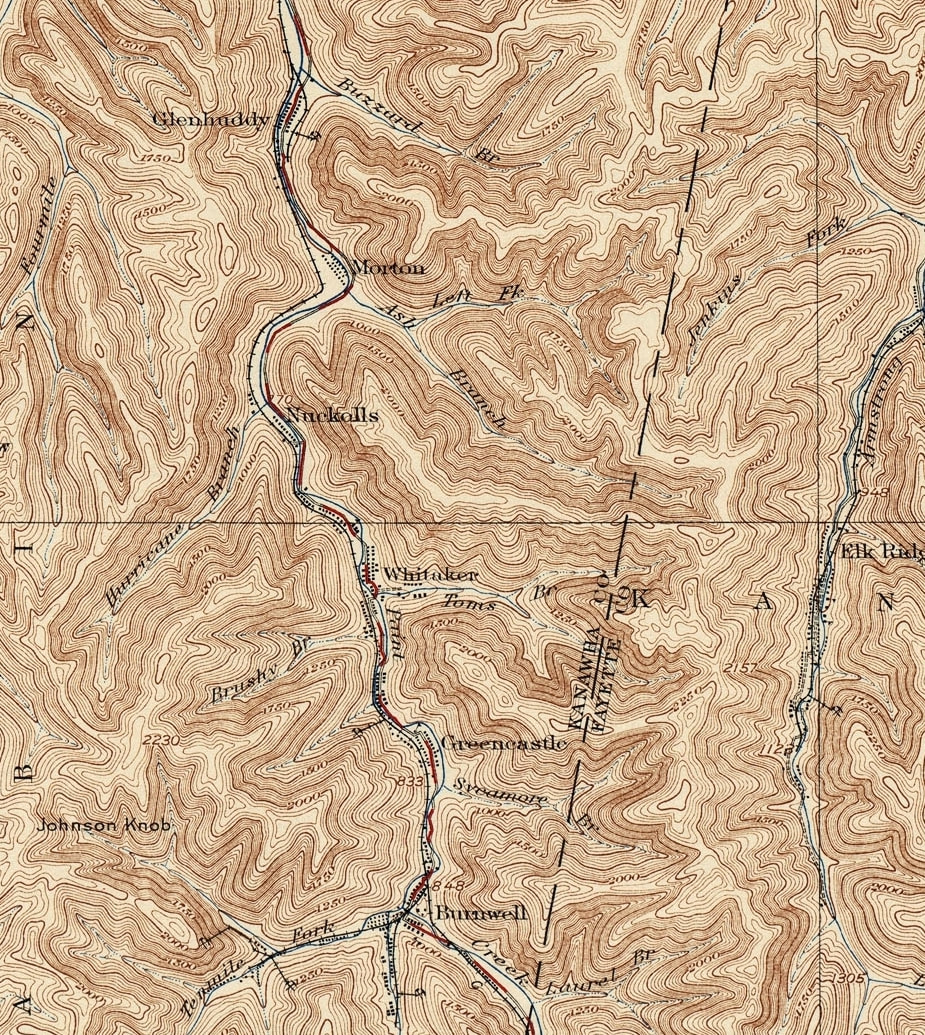

This 1928 topo map encompasses a region of which most has been lost to time. Small coal camps dotted the railroad through this sector along Paint Creek--the most prominent location being that of Burnwell. During the early 1900s when coal mining reached its apex along the creek, mines and tipples lined the mountainsides at Glenhuddy, Morton, Nuckolls, Whittaker, Greencastle, and of course, Burnwell. Today, there are virtually no remaining traces of their existence except for a few homes at Whittaker and Burnwell.

The construction of the West Virginia Turnpike during the early 1950s--and later expansion in the late 1970s--undoubtedly removed many lingering traces of these coal camps. Most have vanished entirely. |

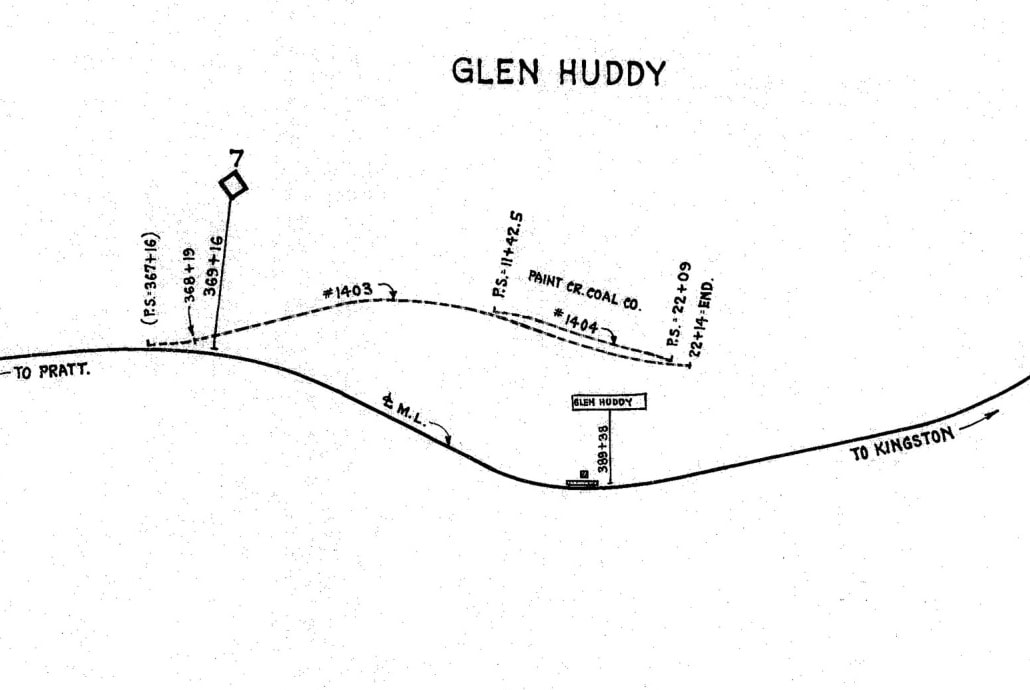

South of Standard and first in companionship with the West Virginia Turnpike is the extinct coal camp of Glenhuddy. Although the C&O Railway occupied the west bank of the creek through here a spur was constructed across the creek to the mine and camp. This community existed in the area immediately south of Buzzard Branch.

|

Glenhuddy is marked as Milepost 7 on the C&O Paint Creek line on this 1937 map. It appears at this date the spur that crossed Paint Creek to serve the Paint Creek Coal Company mine was already abandoned. Map courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

The location of the ghost coal camp at Glenhuddy along the present day West Virginia Turnpike.

|

Glenhuddy was originally known as Detroit--a name likely derived from the presence of the Detroit and Kanawha Coal Company that operated a mine here during the first decade of the 20th century. The site was marred by tragedy on January 18, 1906 when an explosion collapsed the mine shaft killing eighteen miners. In the aftermath, the mine was sold to a syndicate that included both local and out of state firms (often the case). By the 1920s, the community--like several others on Paint Creek--had been renamed to purge an association with a scarred past. From all visible and archival evidence, it appears that mining and the associated camp at Glenhuddy had vanished by the 1930s under the ownership of the Paint Creek Coal Company. The only structure that stands today at an otherwise extinct location is a maintenance facility operated by the West Virginia Department of Transportation.

Situated immediately south of Glenhuddy was the coal camp of Morton. The railroad paralleled the mountainside away from the community which located on ground inside a sharp bend of Paint Creek at the mouth of Ash Branch. A mine was located here operated by the Paint Creek Collieries but the layout is mired in the deep mist of time. If there was a series of spurs to the mine, they either vanished prior to the 1930s or escaped the C&O Railway cartographer. Whether the town disappeared during the Depression era (or prior to) is uncertain but the West Virginia Turnpike construction during the early 1950s transformed the area. A Turnpike rest area for travelers was built on the site once occupied by the Morton coal camp.

|

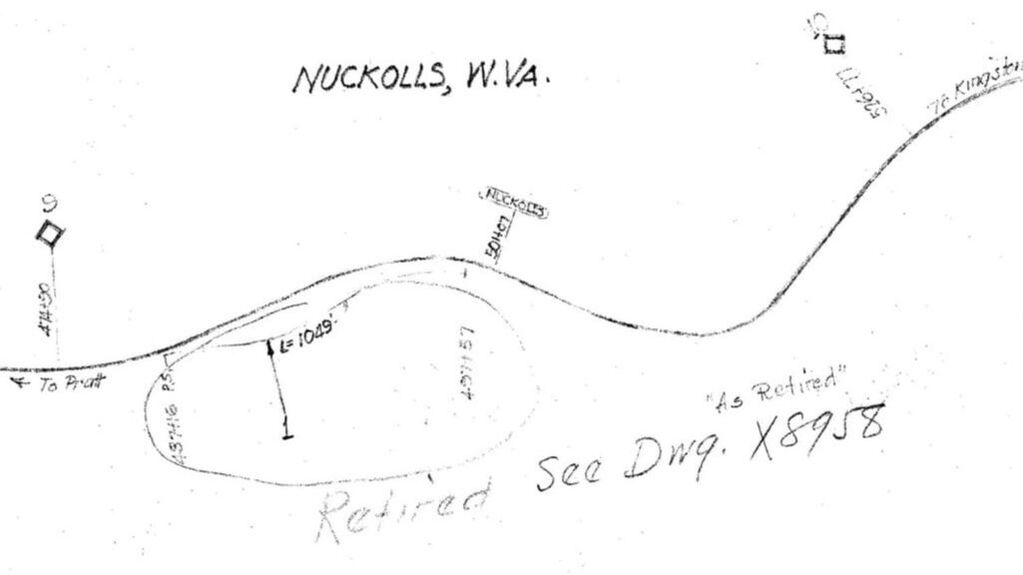

C&O Railway map of Nuckolls from 1937. Located at Milepost 9 on the Paint Creek line, this coal camp is referred to as past tense even at this date as noted with the "retired" reference of the facility that existed there. Map courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

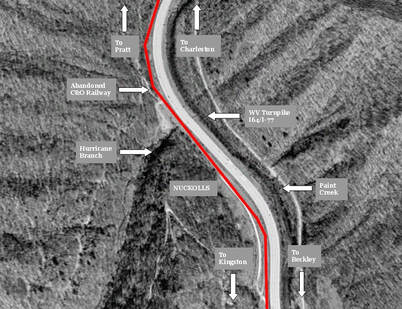

Aerial view marking the site of Nuckolls along Paint Creek. It is a lost location in the truest sense as nothing remains of this long ago coal camp.

|

Another coal camp dispatched to the foggy haze of history is the one once located at Nuckolls. In its heyday of the early 1900s, two companies conducted mining here--the Nuckolls Coal and Coke Company and the Paint Creek Collieries. It is possible that mining continued briefly into the period of the Paint Creek Coal Company ownership although as indicated on the C&O Railway map above it was dormant by the late Depression era. Today there are no visible remaining traces from the Nuckolls coal camp. An exploration of the mountain above the site may reveal hidden relics but this is best suited for cold weather months when the foliage is dropped as well as when rattlesnakes and copperheads are in hibernation. As an added note, the mountain top above Nuckolls was opened as a strip mine site during the early 2000s.

The railroad photographer of yesteryear who deviated from the quantity of main line action to record branch line movements occupies a position of great respect from this author. This priceless 1950s scene looks down from the hillside of an unidentified location at a Class H-6 2-6-6-2 with an empty hopper train along Paint Creek. Imagine driving along the West Virginia Turnpike and witnessing such a sight today. Image courtesy C&O Historical Society.

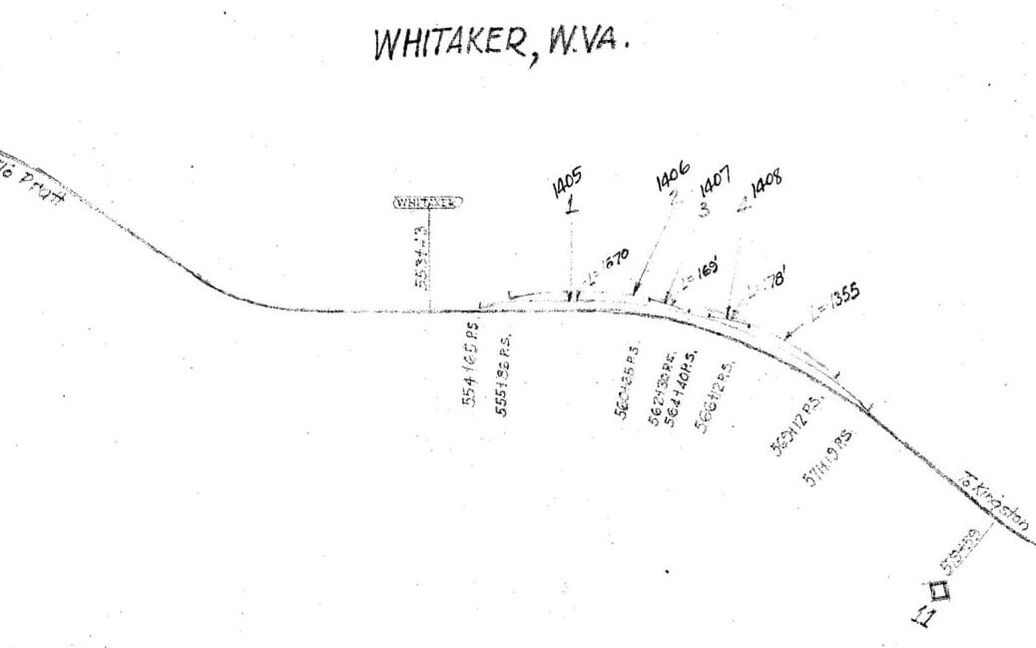

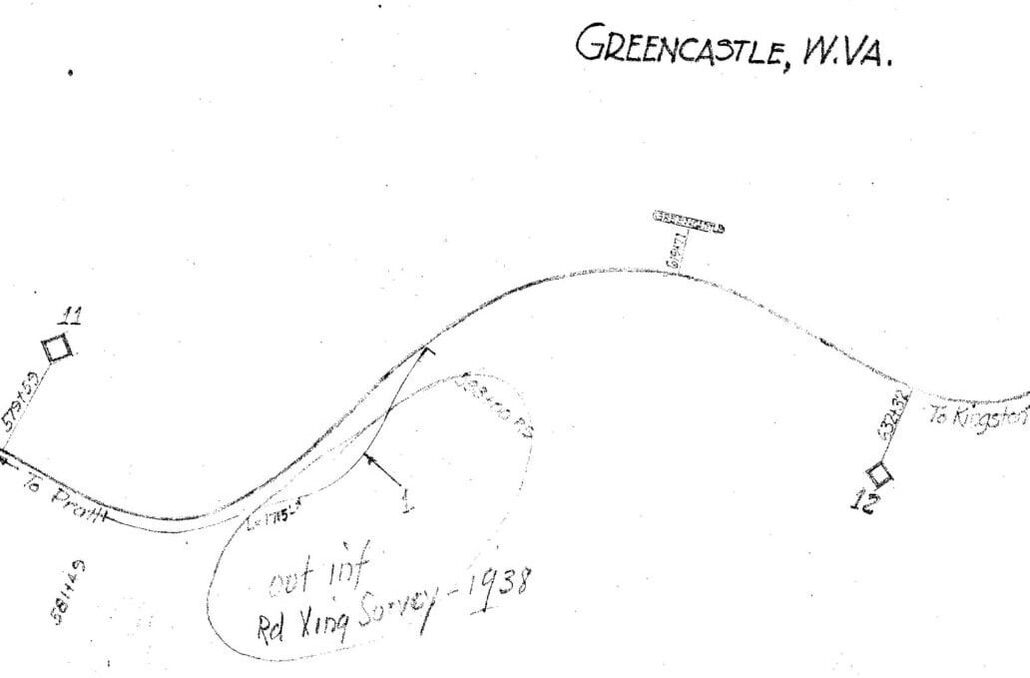

Two C&O 1937 maps covering the territory from north of Whittaker to Greencastle (Milepost 10-12). This region constituted the mid-point of the Paint Creek Branch. At this date, spur tracks are intact indicating the presence of ongoing mining at Whittaker. The map of Greencastle at right--with a 1938 update note---records an area that is idle but for the main line. Both images courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

Aerial map of Whittaker as it exists today. The surviving section is on the east bank whereas the sector on the west side is completely gone.

South of Whittaker is the extinct mining camp of Greencastle. Like Whittaker, Greencastle occupied both banks of Paint Creek with the mines located on the west bank beside the railroad. Two companies operated here during the life span of active mining--the Paint Creek Collieries and the Greenbrier Coal Company. Referencing the C&O Railway map of 1938, it indicates that mining had ceased by that date as there is no active service noted there.

Google Earth view of the area of Greencastle. It is yet another extinct mining camp in the Paint Creek basin with no visible remaining traces.

|

Located midway on the railroad between Pratt and Kingsford is the community of Whittaker. Founded under the name of Tomsburg, it remained an active coal mining camp at least into the 1930s. Two companies, the Grose Colliery Company and the Paint Creek Collieries Company, operated here and it was the latter (as the Paint Creek Coal Company) in the wake of the 1912-1913 Mine War that changed the name from Tomsburg to Whittaker. This former coal camp is an interesting case study today for the fact that in its prime, it occupied both sides of Paint Creek. Only the east bank survives today as a sleepy village kept awake by the roar of traffic on the Turnpike. The west bank where the railroad and mines were located vanished and was further exacerbated by the construction of the West Virginia Turnpike.

|

Imperial Junction

Imperial Junction was perhaps the busiest point on the Paint Creek line at its zenith. So important was the location that the C&O Railway designated the mine trackage that diverged here as a separate subdivision. With the production of coal generated by the Imperial Colliery mines at Burnwell combined with occasional general merchandise traffic, this small subdivision was quite active.

|

Contemporary aerial view of Burnwell overlaid with its past. C&O trackage---both Paint Creek and Imperial Subs---are marked with their respective locations as well as the mine locations and coal camp. The four lane West Virginia Turnpike creates a dichotomy of past and present.

A paradox in time. Highway traffic of today on the West Virginia Turnpike contrasts with the abandoned Paint Creek bridge at Imperial Junction. Dan Robie 2020

|

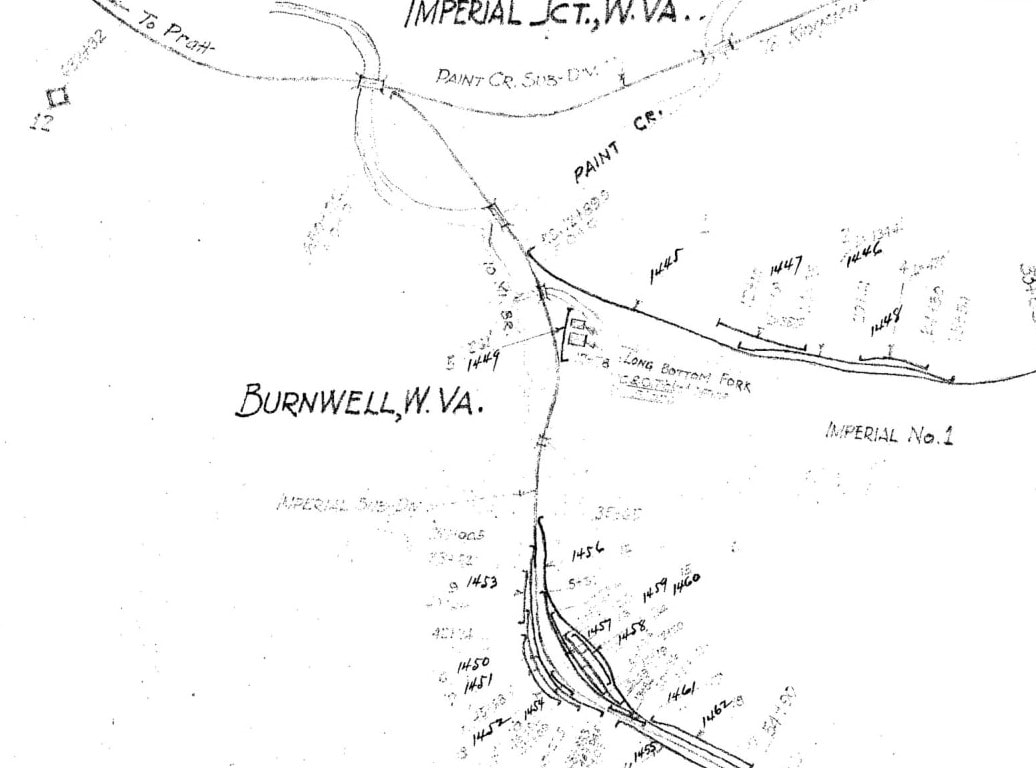

The railroad layout at Burnwell was still diverse when this 1937 C&O map was created. Two forks comprised the Imperial Sub which served three Imperial Colliery Company mines in operation at the date. Notated is the relationship to Paint Creek and the bridges spanning the stream as well as a short crossing of Long Branch. When one visits the vestige of Burnwell that remains today, it is mesmerizing that all on this map once existed. Map courtesy C&O Historical Society

Only the rushing water of Paint Creek remains a constant today as the Imperial Junction bridge no longer bears the weight of trains. Upstream view around the bend at Burnwell. Dan Robie 2020

|

We can thank the great C&O photographer Gene Huddleston for recording scenes such as this for future generations to admire. In the relatively simpler time of 1962, a caboose brings up the rear of a coal train passing Imperial Junction (Burnwell). The caboose, the sign, the whistle post, and the house--a portrait of charm from the glorious past on the railroad. Image courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

Northbound view of the right of way at Imperial Junction. Looking across the Paint Creek bridge on the C&O main. Dan Robie 2020

|

Imperial Junction as it appears today--C&O main straight and Imperial Sub diverging. Little here to remind one that this was among the hottest spots on the Paint Creek Branch. Dan Robie 2020

|

C&O GP9 #6136 and a sister with a coal train at Imperial Junction during the early 1960s. The Paint Creek line was still a busy railroad during this era. Image courtesy C&O Historical Society

Burnwell

The extinct coal camp of Burnwell is among the best remembered of literally hundreds that once populated the mountains and railroad rights of way in southern West Virginia. It was the southernmost point (in its entirety) along the Paint Creek Branch in Kanawha County almost scratching the border with Fayette County.

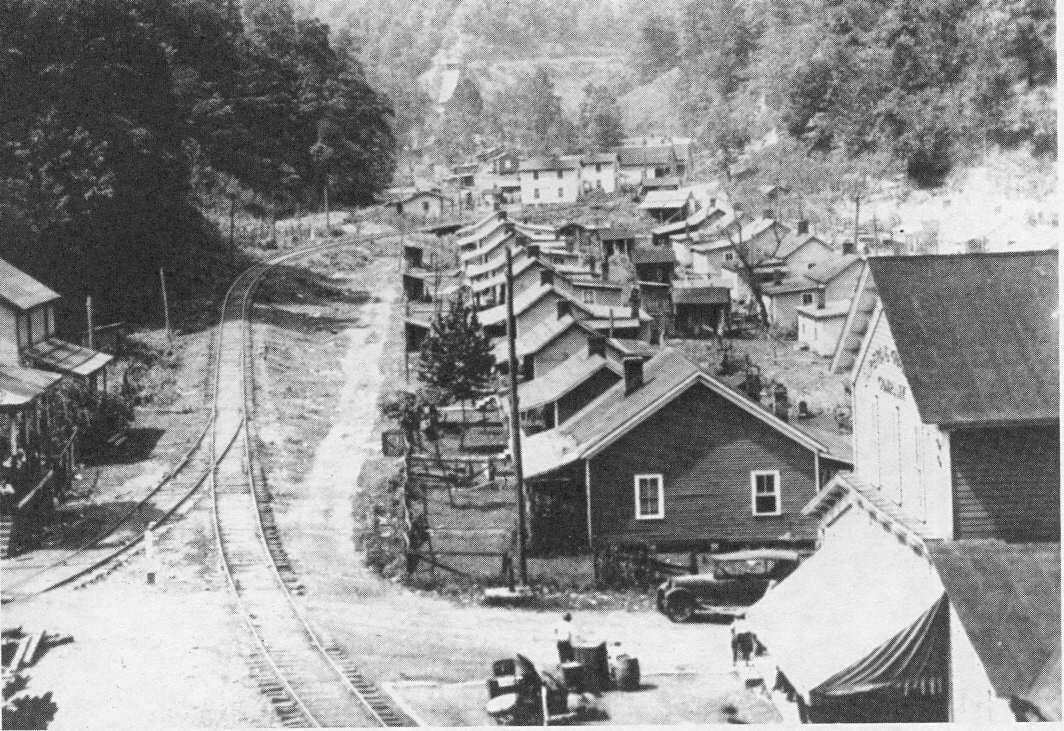

The coal camp of Burnwell in its heyday during the 1920s. A quintessential Appalachian coal town, it is defined by the rows of company homes and the railroad passing directly through. At right is the Imperial Colliery company store and the railroad-- a branch from the Paint Creek line designated as the Imperial Sub--served the Imperial Colliery Company mines. Everything in this scene has passed into history. Image courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

The girder plate bridge spanning Paint Creek on the Imperial Sub. All of the traffic to and from the Burnwell community including the mines crossed this structure. Dan Robie 2020

|

The Imperial Colliery Mine #1 tipple at Burnwell shortly after it opened. This photograph dates to the time period of 1903-1904. Image courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

Of all the coal communities that emerged along the Paint Creek basin, Burnwell, perhaps, is the most intriguing for a number of reasons. As camps go--certainly on Paint Creek, it was large with multiple mines in simultaneous operation. The C&O constructed a branch line from the from the main stem to serve the mines classifying the trackage as the Imperial Sub that also included a house track for merchandise. Rows of company houses lined the Imperial Sub---in fact, the camp also included a YMCA. Burnwell was the stereotype coal camp in nearly every respect during the first half of the 20th century. Many a carload of black diamonds originated here that provided revenue and kept the rails shiny for the C&O.

|

Coal company stores were fixtures in the mining camps. They were necessary evils in one respect---while providing for the needs of the residents, they were typically owned by the local coal operator which often required its employees to spend their wages there. The Imperial Colliery store was notable for its longevity. It remained in business until 1993--long after the mines ceased--when it burned from the malicious intent of an arsonist. This was the last active company store in West Virginia. Image courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

Burnwell was effectively established in 1901 when the Christian family of Lynchburg, VA founded the Imperial Colliery Company. Within two years, the first mine opened inaugurating mining activity around the region for the next 80 years, By the 1920s, four mines were in operation--ultimately, the Imperial Colliery Company would develop 24 mines in the region throughout the years although they were not active at the same time. Nor were all apparently accessed by the C&O Railway for direct loadout. The original four mines were served by the C&O and on the map above, the trackage to at least three of them was intact in 1937.

|

Double span girder plate bridge at the south end of Burnwell. View is southbound. Dan Robie 2020

|

The lasting legacy of Burnwell can be further attributed to the Imperial Colliery Company store that held the distinction of the last operating company store in West Virginia. Long after the last mines idled the store remained in business existing as an anachronism of a bygone era serving local residents and travelers who ventured off the West Virginia Turnpike. Unfortunately, this unique business came to an abrupt end in 1993 when the structure was destroyed by arson. Interestingly, the Imperial Colliery Company remains in business today leasing various assets. The once bustling coal camp of Burnwell today hosts only a few homes and a church.

|

Since crossing Paint Creek at Standard, the railroad remained on the west bank of the stream until reaching Burnwell. Adding more interest for the explorer is the fact that four railroad bridges were built here--two on the Paint Creek Sub and two on the Imperial Sub. Two bridges were necessary to bypass a loop in the creek at Burnwell--one at Imperial Junction and another at the south end of Burnwell but the railroad nevertheless continued south on the west bank. The Imperial Sub also crossed Paint Creek as well as a smaller structure spanning Long Branch.

Hickory Camp to Milburn

|

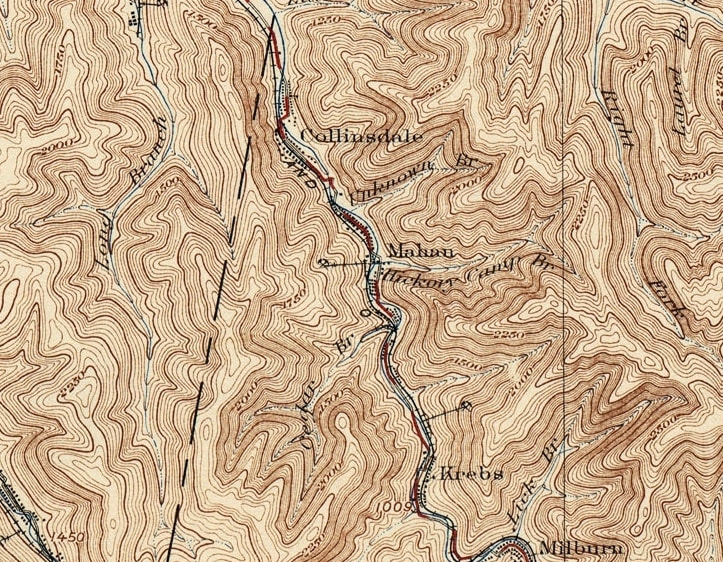

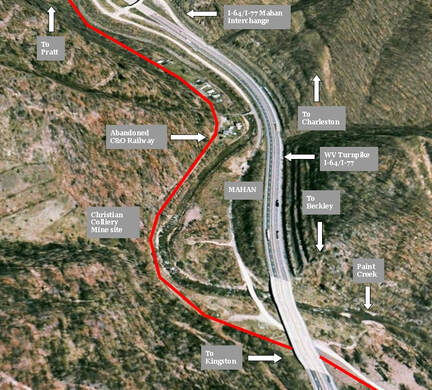

Continuing south and upstream along Paint Creek, the railroad crossed into Fayette County and touched more mining camps that emerged along the route. Perhaps the most recognizable town name along Paint Creek to the casual observer is Mahan by virtue of a Turnpike highway exit. Other camps in this sector included Collinsdale, Coalfield, Krebs, and Milburn. This region is sparse with few remaining telltale signs of a mining past. In terms of size today, only Collinsdale and Mahan exist as small residential hamlets.

|

Hickory Camp

|

Tragedy at Hickory Camp: H-6 2-6-6-2 #1485 is overturned from a derailment at Hickory Camp January 30, 1952. The locomotive picked a switch with its tender jack knifing before overturning. Sadly, the accident resulted in a crew member fatality. Image courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

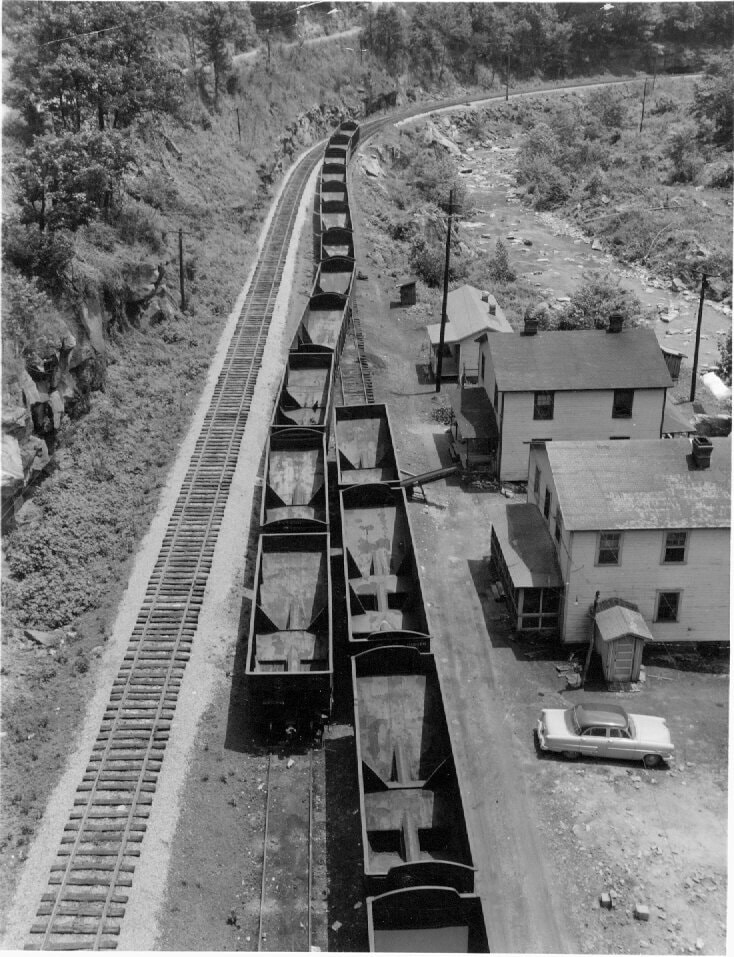

A train of coal empties waits in the siding at Hickory Camp for the passage of a northbound loaded train. This 1962 photo reveals a time when the siding was utilized. Image courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

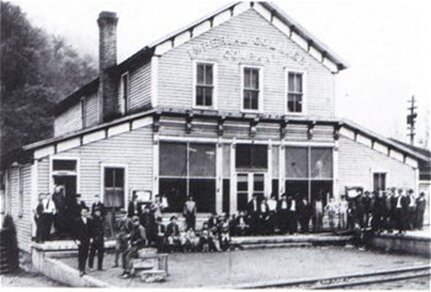

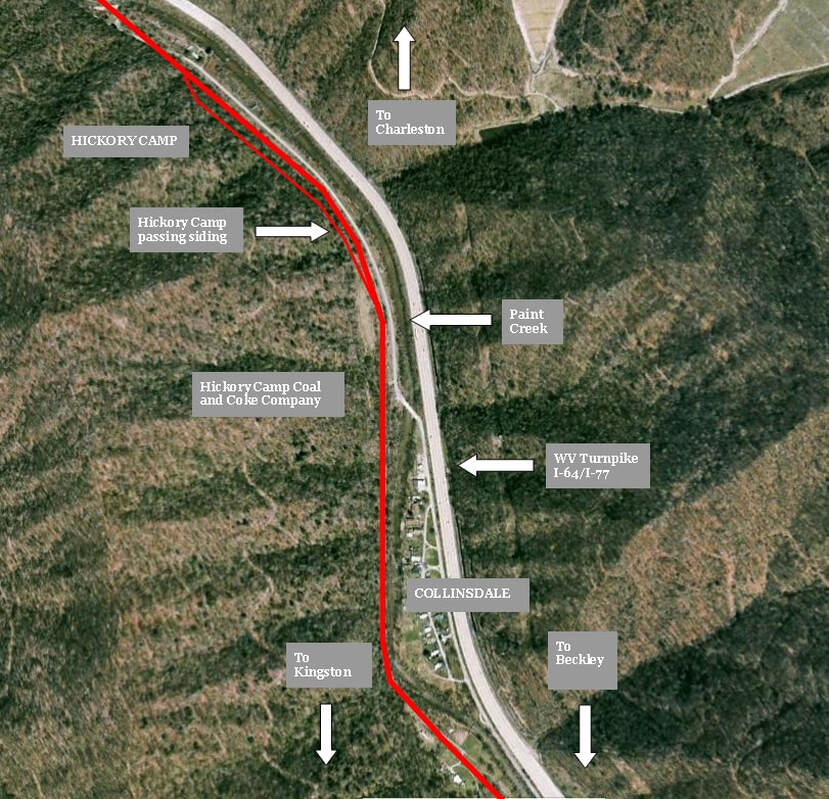

Straddling the Kanawha-Fayette County line were the co-existing locations of Hickory Camp and Collinsdale. The former was primarily a C&O Railway location identity while the latter more directly referred to the coal mining camp once located here. Collinsdale was the site of the Hickory Camp Coal and Coke Company that began operations early in the century. By the 1930s, however, the company had ceased as referenced on the 1937 C&O Railway map below. Once the mining dissipated the majority of the population left the area but Collinsdale survives today as a small residential hamlet along the West Virginia Turnpike.

|

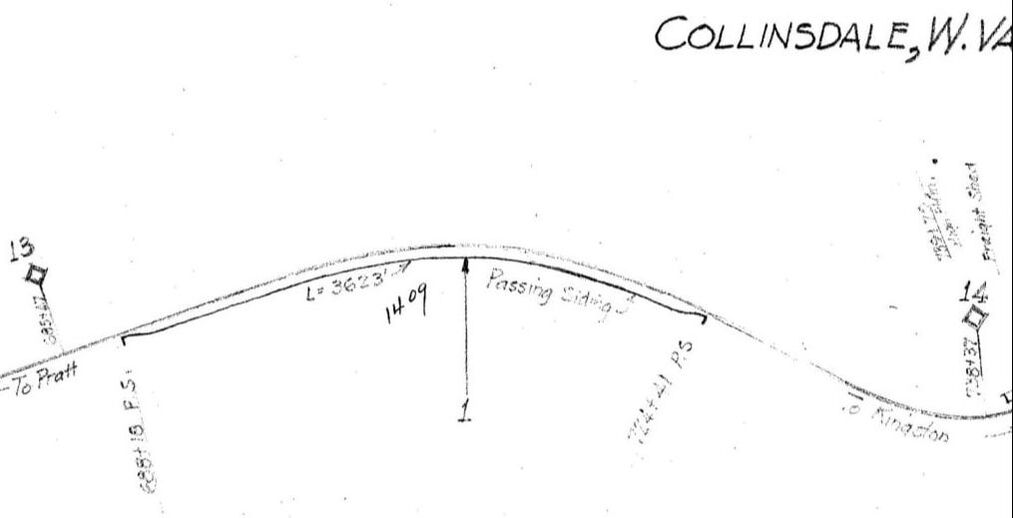

1937 C&O Railway map of the Collinsdale region from Milepost 13 to 14. This area was known on the railroad as Hickory Camp and the location of a 3600 foot passing siding. Map courtesy C&O Historical Society

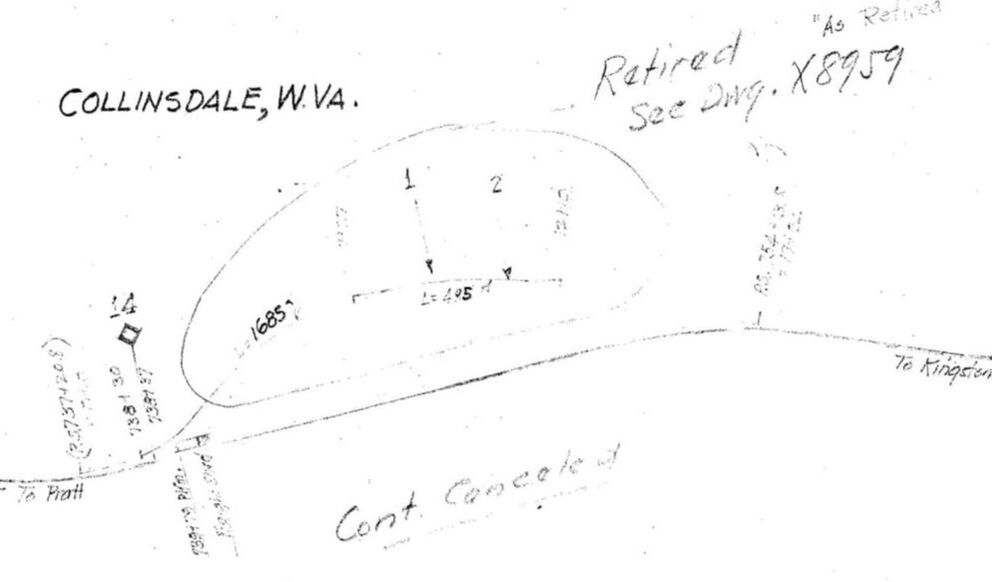

|

The extinct mining camp at Collinsdale as noted in 1937. Out of service trackage circled on the map was the Hickory Camp Coal Company. Map courtesy C&O Historical Society.

|

Although company homes were scattered along Hickory Camp its primary importance to the railroad was as a location for a strategically necessary 3600 foot passing siding. A few miles beyond the halfway point of the Paint Creek line, it would accommodate meets for trains of loads and empties in earlier times when the number of trains was frequent. Also since it was situated to the south of Burnwell, it enabled any runaround movements of trains working the Imperial Colliery Company mines located there.

Google Earth view of the territory encompassed by Hickory Camp and Collinsdale. The West Virginia Turnpike continues its companionship with the former mining and railroad region presenting the contrast of newer and old. Of note historically here are the sites of the important Hickory Camp passing siding and the Hickory Camp Coal and Coke Company.

Hickory Camp was the site of a tragic accident that occurred on the evening of January 30, 1952 . A train led by H-6 2-6-6-2 # 1485 picked the switch points at the passing siding causing it to derail. The conductor on the train, Samuel L. Garrett, was riding on the gangway between the locomotive cab and tender when the accident occurred. During the sequence of events, the tender jack knifed to the locomotive cab fatally crushing Mr. Garrett with the #1485 subsequently falling on its side. A wreck train was dispatched from Handley to re-rail the locomotive and repair damage. The photo above is one of several that were taken of the aftermath the following day.

Two views the right of way at Hickory Camp (left) and and north of Collinsdale at right. This area was the location of the Hickory Camp passing siding as the wider right of way at right indicates. Dan Robie 2020

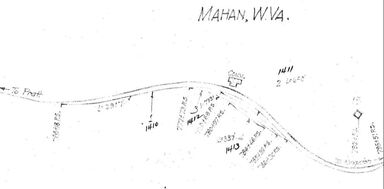

Mahan

Mahan is perhaps the most familiar name along the Paint Creek basin by virtue of the West Virginia Turnpike. Thousands of drivers see it daily and it is the only community identified on the highway with its own interchange for access to it and paralleling Paint Creek Road which passes through the extinct coal camps of yesterday.

|

The railroad district through Mahan as it was recorded in 1937. Sandwiched between Mileposts 14 and 15, additional tracks were located here to serve the mining interests of the Christian Colliery. Map courtesy C&O Historical Society

Modern Mahan with its past indicated in context. A small residential section is all that remains from its mining heritage.

|

Turning back the hands of time will reveal Mahan as a vibrant coal community. The chief operation here was the Christian Colliery Company which was affiliated with the Imperial Collieries at Burnwell. In this particular instance, the mining company was named for the Christian family which owned both. The C&O Railway was a major player in its local economy with cars to and from the Christian Colliery mines located just south of the center of town. Mahan was replete with company houses along with the commercial hub of the community, the Christian Collieries company store.

Mahan as it was during the early coal boom years circa 1920. This view looks southwest through the community offering a glimpse of houses and a structure that was possibly the Christian Colliery company store. The photograph appears to have been taken after a period of heavy rain. Image West Virginia Geological Surveys

|

Mahan was bustling with activity judging by the number of automobiles in this circa 1940 photo. The Christian Colliery company store was the commercial and social hub of the community. Image courtesy C&O Historical Society

Empty hoppers fill the side tracks at Mahan in a scene from the 1950s. This era was the twilight of the Christian Collieries as it had ceased operating by the end of the decade. Image courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

A touch of irony about the camp is that is was named after Peter Mahan who was a prominent businessman in the lumber industry rather than that of coal. But black diamonds ultimately impacted the area in 1911 when the Christian Colliery Company began opening mines and for the next 40 years, were the lifeblood of the community. During the 1950s, the region began to fade and its population migrated elsewhere. The Mahan of today is a far cry from its mining heyday but descendants remain in the small residential section that still exists.

|

Circa 1915 photo of the girder plate bridge spanning Paint Creek between Mahan and Coalfield. Image West Virginia Geological Surveys

|

This girder plate bridge between Mahan and Coalfield remains as a rusty anachronism from a bygone era. Three decades have passed since the last train crossed Paint Creek on this structure and the approaches on both sides have since eroded away. Dan Robie 2020

|

South of Mahan the railroad crossed over Paint Creek to its east bank--the first significant bridge on the line since Burnwell. It would continue on this side of the creek until reaching the south end of Westerly.

Coalfield and Krebs

|

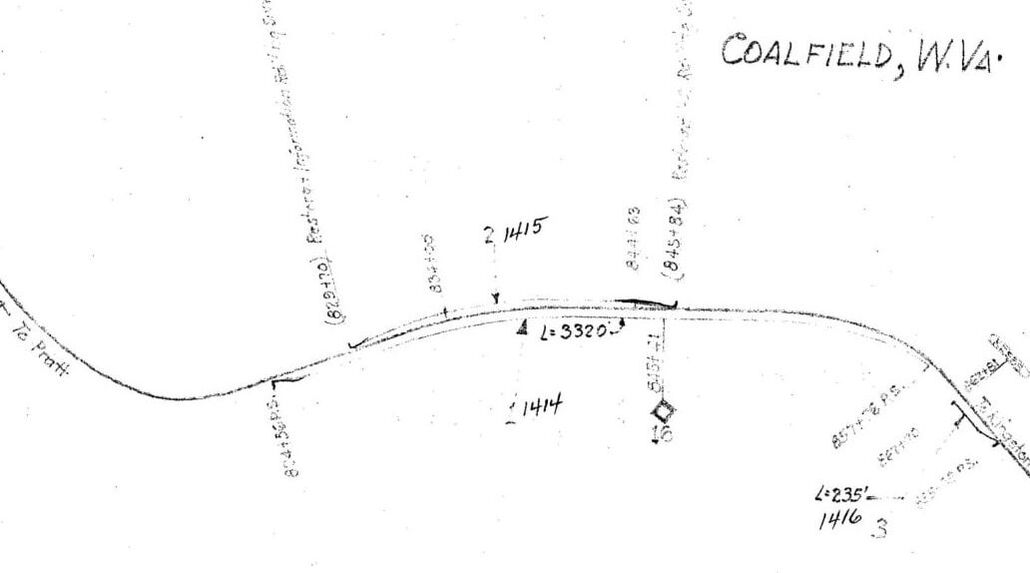

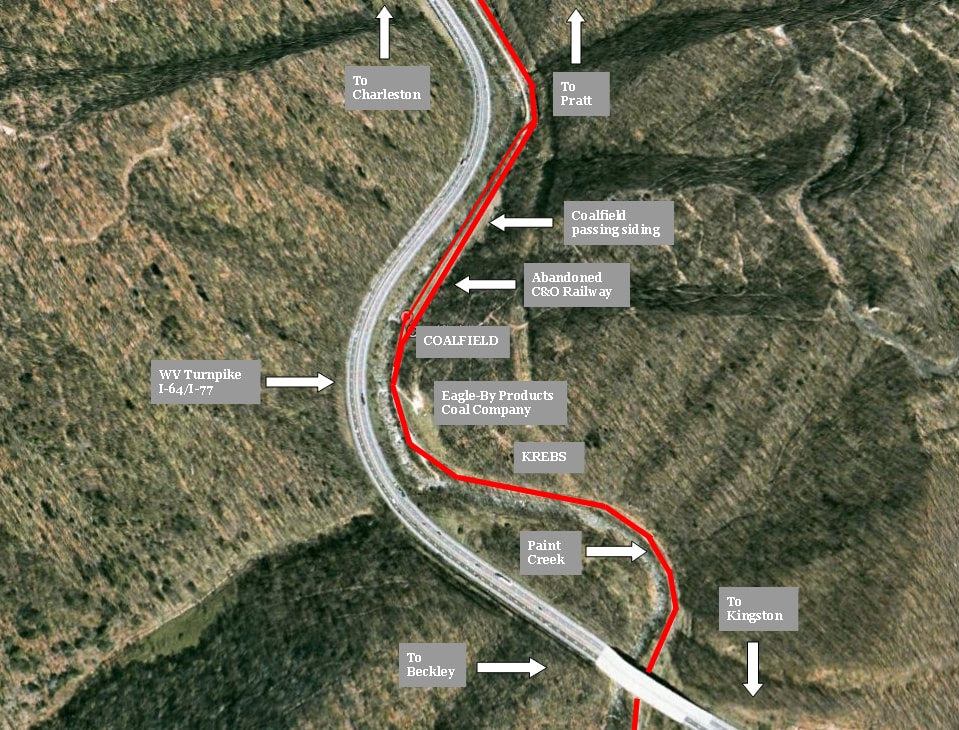

C&O Railway map from 1937 of the dual location of Coalfield and Krebs at Milepost 16. A 3320 foot passing siding was located here and the mine spur at extreme right belonged to the Eagle By-Products Coal Company. This location was often cited on maps by the name of Krebs. Map courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

The ghost camps at Coalfield and Krebs with their relationship to the West Virginia Turnpike. Few reminders exist of the camps and mining once located here.

|

Continuing south, the next location on the railroad of consequence was one that was known by two names during the course of its history. Early topographical maps identify the locale as Krebs; however, later maps by the mid-1900s began noting it as Coalfield. Perhaps Krebs was associated with the actual mining here by the Eagle By-Products Coal Company whereas Coalfield pertained exclusively to the C&O Railway and small camp of which recognized this identification.

|

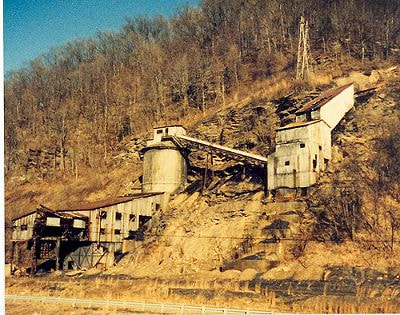

The abandoned Eagle By-Products Coal Company mine at Krebs in the 1980s. This structure caught the eye of many a traveler on the West Virginia Turnpike until it was demolished in the 1990s. Image courtesy of Kathy Cummings

|

Coalfield in the aftermath of the 1932 Paint Creek flash flood. Two structures have washed onto the railroad right of way including a school house visible in the foreground. The Coalfield passing siding is the track diverging at left. Image courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

Although the volume of carloads for the railroad at Krebs was small the location was important to the railroad with the Coalfield passing siding. During the early years on the Paint Creek line, meets occurred here and it undoubtedly aided in switching and for runaround moves for traffic at Krebs and Milburn. Until the 1990s, an abandoned Eagle By-Products Coal Company mine stood in ruins as one of last symbols of coal heritage on Paint Creek. Visible from the West Virginia Turnpike, it was an eye catching anachronism from a bygone era until it was demolished. Today, Krebs/Coalfield is but one more extinct location as nothing remains from the mining years.

Not ideal light for Gene Huddleston to take photographs but we are grateful he followed through this day. This 1970s Chessie System era photo captures the essence of Appalachia during inclement weather. C&O GP7 #5713 and a GP9 pass through Coalfield with a train in the aftermath of a rain storm. The dark valley and rising mountain mist create a poignant atmosphere. Image courtesy C&O Historical Society

Two right of way views at Coalfield (Krebs) looking north and south, respectively. This location corresponds with the 1980s photo above of the Eagle By-Products Coal Company and slightly north of the Gene Huddleston photo location also above. Both images Dan Robie 2020

Milburn

|

Northbound view of the Milburn Coal Company at Milburn possibly during the 1930s. As coal camps went, Milburn was small in size but mining was extensive here remaining until the end of service on the railroad. Image courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

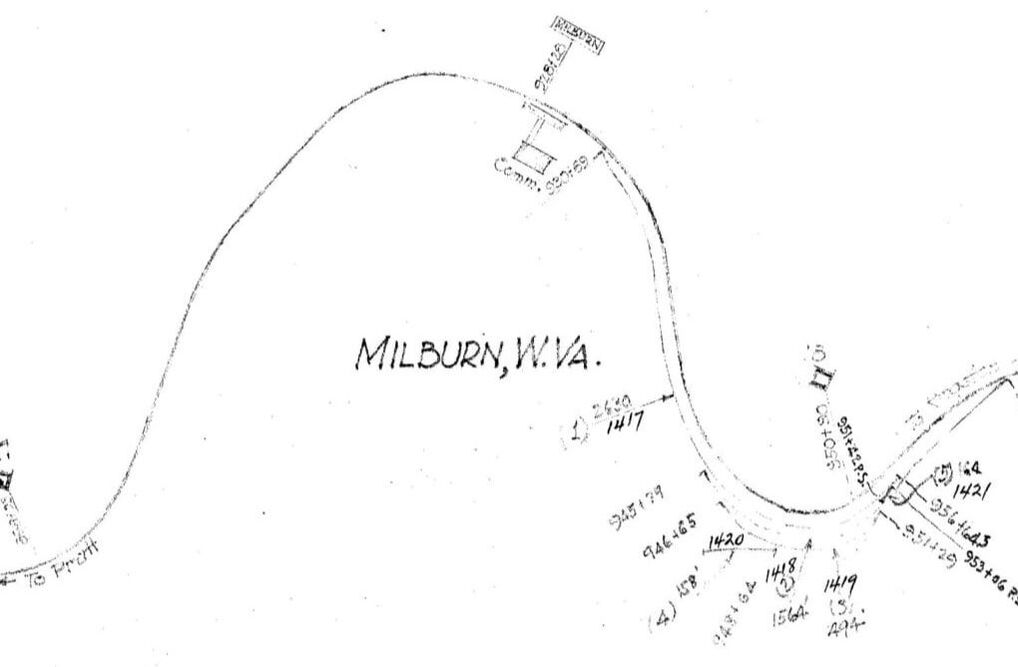

Milburn was located at the 17 Milepost of the C&O Paint Creek line. The 1937 railroad map notates the trackage which existed here during the era of the Milburn Coal Company. Map courtesy of C&O Historical Society

|

The mining camp of Milburn was a relative latecomer to the Paint Creek basin. Developed during the 1920s, it became the domain of three different coal companies during its life span--the Milburn Coal Company, Milburn By-Products Coal Company, and the Milburn Collieries. Similar to Mahan, the camp was located downstream from the mines on a relatively flat sector of land within a bend of Paint Creek.

The coal camp of Milburn once lay on scarce bottomland of Paint Creek with the mining operations about a half mile upstream. Real estate once occupied by the Milburn Coal Company and successors is now reclaimed as it reverts to nature. Elevations increase dramatically as evidenced by the mountains, falls of Paint Creek, and the former railroad right of way.

|

Unabated growth chokes the right of way at Milburn. This view is northbound at one of the bends located here. Dan Robie 2020

|

Late afternoon sun highlights the barren trees along Paint Creek between Milburn and Westhaven. A truly scenic stream in this region. Dan Robie 2020

|

Milburn was one location beset by the construction of the West Virginia Turnpike. Numerous homes were taken by its construction and a lawsuit emerged during the 1950s as to whom was the legal recipient of funds paid by the West Virginia Turnpike Commission for the acquisition of right of way. As one of the last areas developed by mining on Paint Creek, it resulted in Milburn--except for activity around Kingston--as the final active coal camp to remain in existence. But controversy again entered the limelight prematurely ending mining there. In 1989, the Milburn Colliery leased its mines to Mountain Minerals, Inc. which hired non-union labor. In retaliation, the affected union workforce bombed a mine portal and burned the coal tipple in addition to other acts of destruction. These actions effectively caused the demise of mining at Milburn. Three decades later, nary a trace of the mining camp at Milburn remains relegating it to the status of extinct.

Westerly and Kingston

|

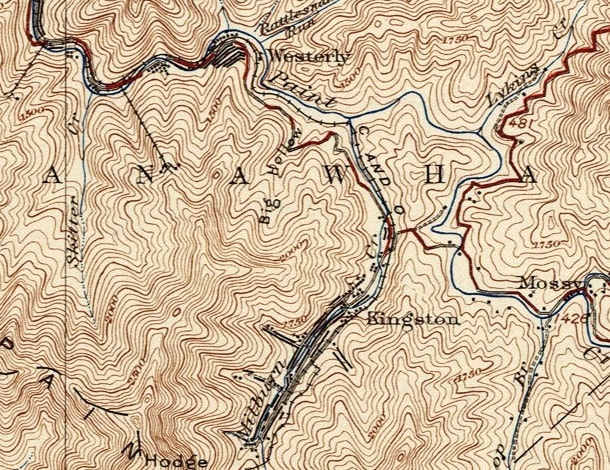

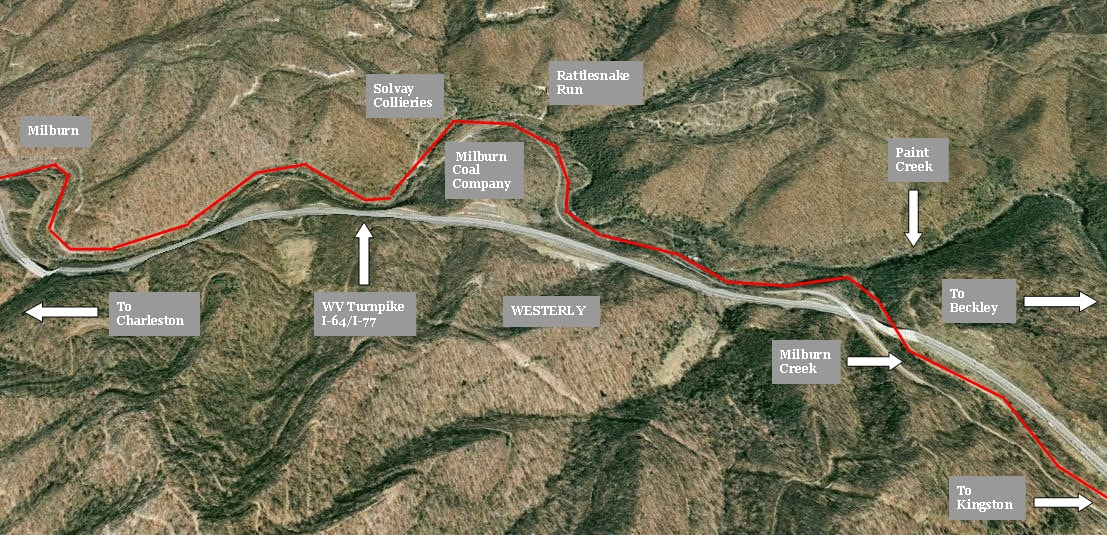

The mountains rise in elevation as one travels the upper Paint Creek basin and the stream itself rushes over a series of falls. Southernmost on the the C&O Paint Creek line were the coal camps of Westerly and Kingston. Formerly known as Keeferton, Westerly was the original end of the line until the Kingston area was developed. Today the area at Westerly is a ghost town and the Kingston of bygone years has vanished into history. The late 20th century witnessed a renaissance of renewed coal mining at Kingston but without rail service by CSX.

|

Westerly (Keeferton)

Google Earth view of Westerly situated between Milburn and Kingston. The mountainous topography is in evidence moving upstream along the Paint Creek basin and the railroad was on a pronounced gradient here on its trek to Kingston. A once active location, the ghost camp of Westerly lay on a scenic sector of Paint Creek highlighted with waterfalls.

Another on the list of coal camps associated with Paint Creek that was founded and later underwent a name change is Westerly. Originally known as Keeferton, the name was changed during the aftermath of the 1912-1913 Mine War perhaps to follow other communities downstream by ending connotations with that dark, turbulent period.

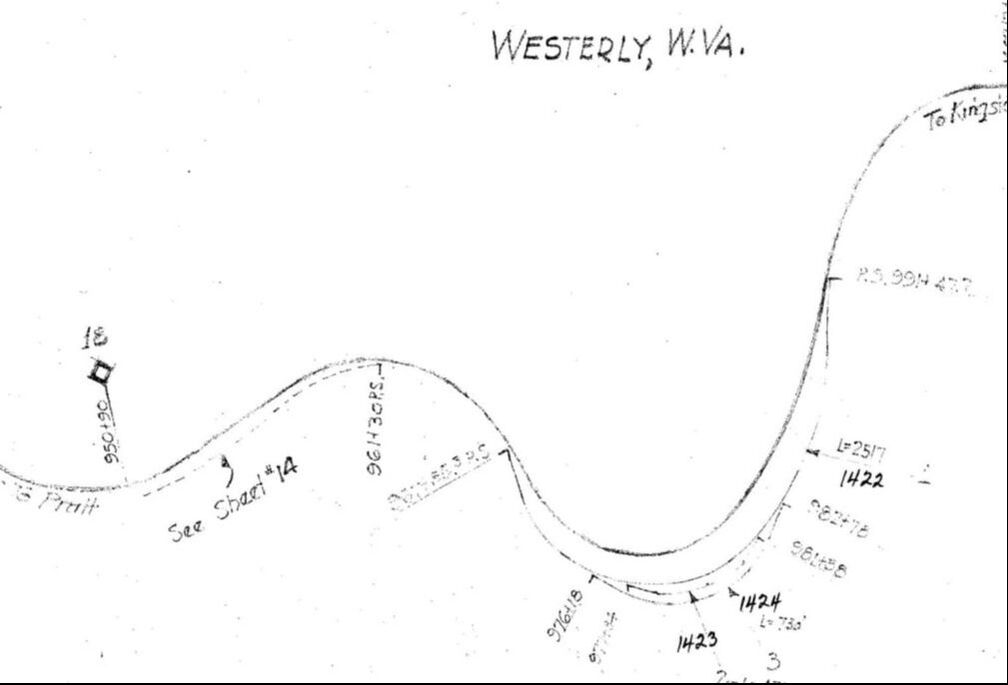

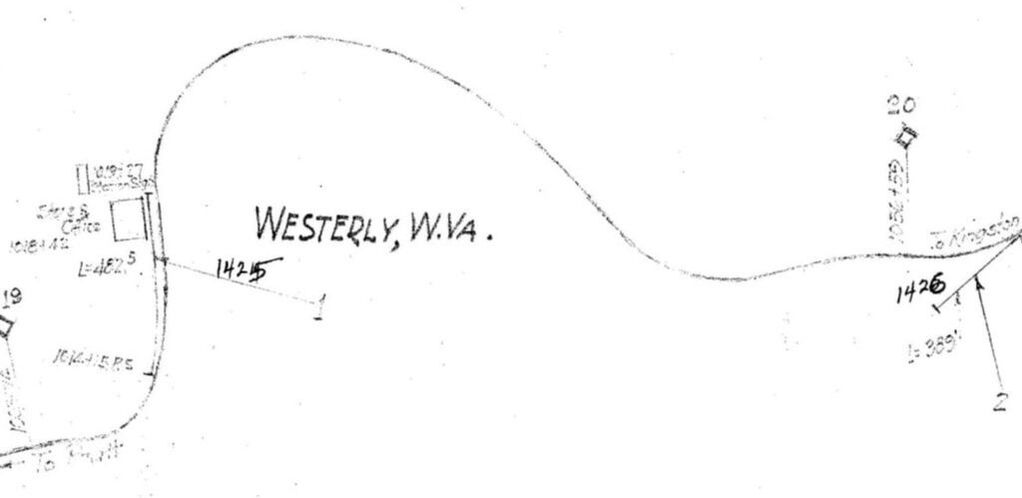

Westerly was still an active mining camp when these 1937 C&O Railway maps were produced. The territory included here is Milepost 18 at the north side extending to Milepost 20 at the south end approaching the Kingston. The mine trackage on both maps was that of the Solvay Collieries and on the one at right at Milepost 20, a runaway track for the descent from Kingston. Maps courtesy C&O Historical Society

Two separate companies operated mines here--the Solvay Collieries which was succeeded by the Pocahontas Coal Company in 1923 and another loadout owned by the Milburn Coal Company. The C&O 1937 maps reveal the existence of both companies and associated plant built to serve them. Westerly was rugged territory for the railroad--the line was on a pronounced gradient that also required switching the loads and empties at the mines. Indicative of the topography here was the existence of a runaway track located on the line at the south end of Westerly on the grade to Kingston. An examination of archival aerial images reveals that the heyday of activity here was gone by the 1960s.

Two GP9s return north on the Paint Creek line bound for Pratt and Handley with only four loaded hoppers this day. The location of this 1970s era photo is unidentified but the topography appears to be in the vicinity of Westerly. Photo courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

Paint Creek is arguably at its scenic best at Westerly. The creek cascades over a series of falls of which the one pictured is known as Westerly Falls. Abandoned C&O right of way is on bank across the creek. Dan Robie 2020

|

The view railroad north at Westerly of the right of way and the girder plate bridge located here. Uncounted hoppers once crossed this span laden with coal from the mines at Westerly and Kingston. Dan Robie 2020

|

A visit to the Westerly area today will enlighten the explorer as to the beauty of Paint Creek here. The valley is deeper as the mountains rise in elevation and the creek passes through a series of falls highlighted by the Westerly Falls. It is a popular section of the Paint Creek Rail Trail as well as a destination for the fisherman in search of trout. In terms of the railroad, C&O Paint Creek photos are relatively uncommon but even in that vein it is unfortunate that few were taken in this distinctive area.

The railroad at Westerly extending to Kingston existed on the steepest gradient found on the entire Paint Creek Branch. Moving upstream along the creek the elevation rose exponentially and when the railroad was extended in 1911, it turned at the mouth of Milburn Creek to reach the new camp at Kingston.

Kingston

A trace of snow covers the abandoned right of way slightly north of Kingston. The steep gradient is apparent here on the climb between Westerly and Kingston. Dan Robie 2020

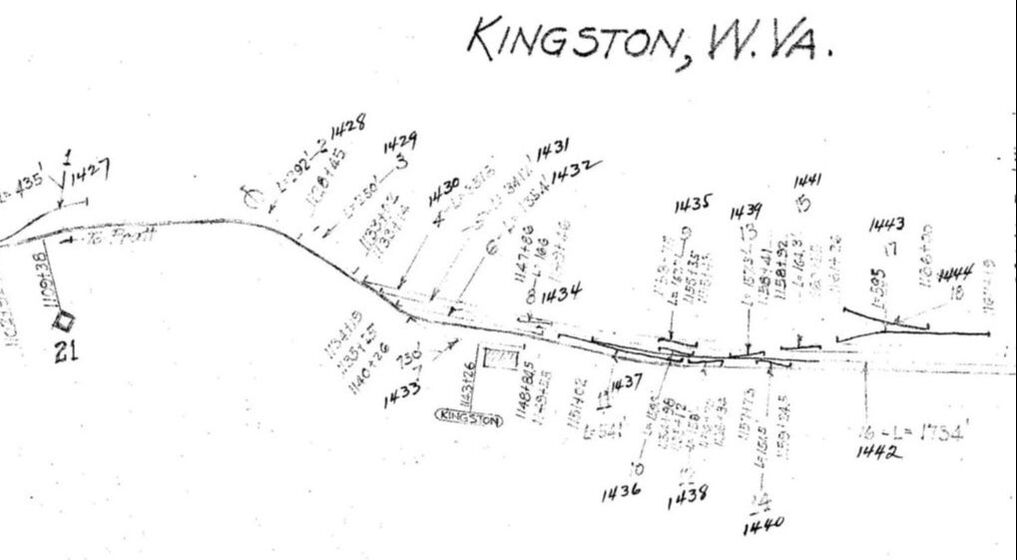

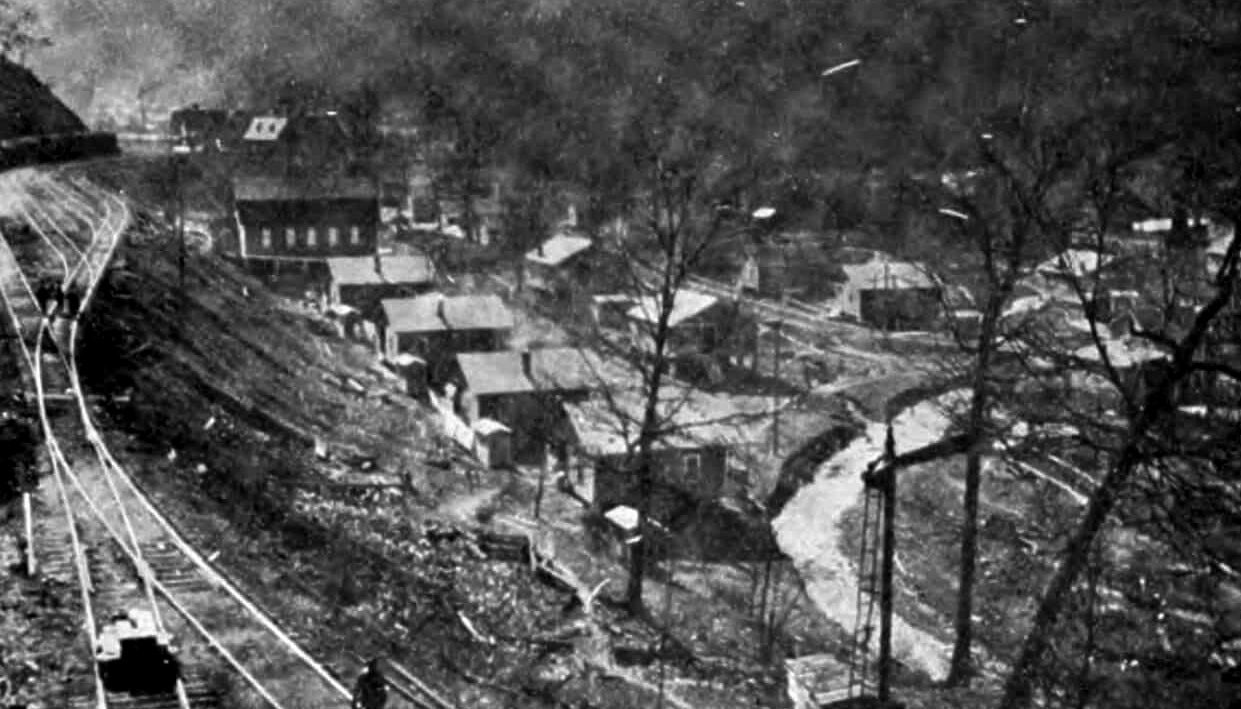

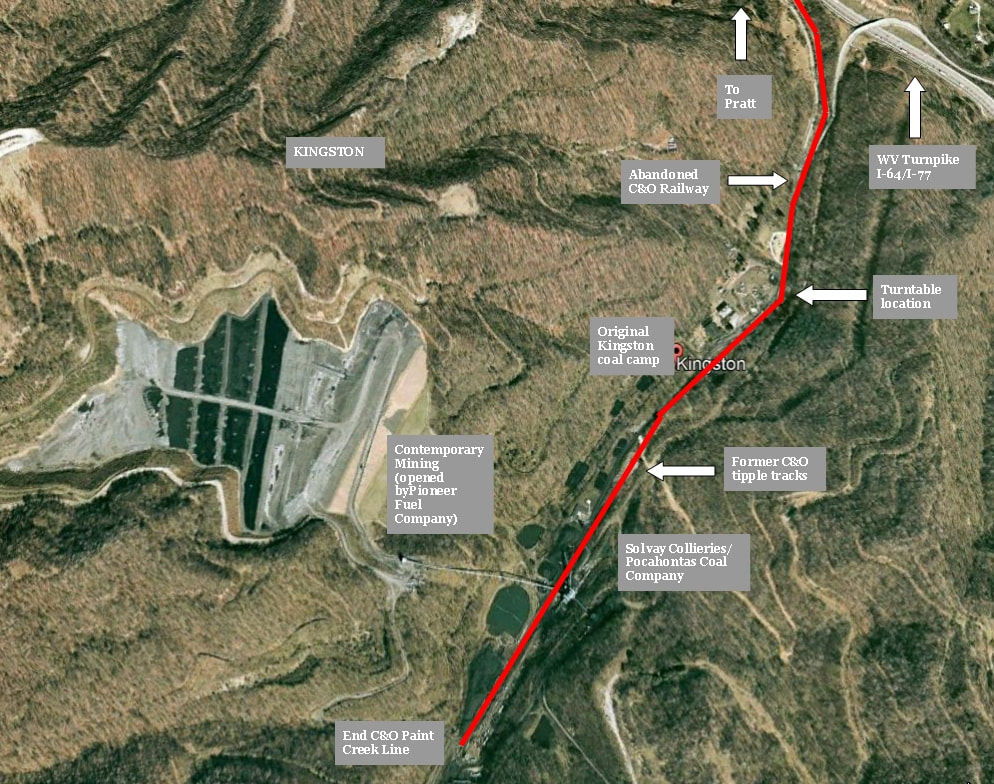

In 1910, additional mining opened along the C&O Paint Creek line with the development of the Solvay Collieries coal camp at Kingston. The following year the C&O extended the line from Westerly a couple of miles to serve this new region and constructed facilities to accommodate what ultimately became the end of the line. During its heyday Kingston had an extensive configuration complete with multiple yard tracks and a turntable to spin steam locomotives for the return trip northbound .

Kingston marked the end of the C&O Paint Creek branch terminating beyond the 21 Milepost. Multiple tracks served the mines operated by the Kingston-Pocahontas Coal Company and Solvay Collieries. The location of the turntable is indicated to the right of the 21 Milepost. Coal mining continues at Kingston during the 21st century but the railroad and associated coal camp of yesteryear belongs to history. Map courtesy C&O Historical Society

|

The coal camp of Kingston during its zenith circa 1920. Although the subject of the photograph is the town itself---the company houses and other facilities----a glimpse of the yard trackage found its way into the viewfinder for posterity. All that appears in this image now belongs to the ages. Image West Virginia Geological Surveys

|

C&O Railway 2-8-0 Consolidation #299 on the turntable at Kingston circa 1911. It was later sold to the White Sulphur and Huntersville Railroad in mid to late 1912. Image contributed by Scott M. Greathouse

|

The original camp at Kingston reached its peak during the 1920s attaining a population of nearly 2500. It claimed two YMCAs, a theatre, and a bowling alley among its amenities—often a rarity for such luxuries in the mining camps and towns of the coalfields. In 1923, the Kingston-Pocahontas Coal Company assumed control of operations at Kingston and remained the primary operator until the years following World War II. Ultimately, the coal production ebbed and with it, the departure of the population. Kingston, not unlike other mining camps along Paint Creek, simply disappeared from the landscape through the passing years with only a few structures left as sentinels from a long past era. In spite of the disappearance of the original Kingston camp, however, mining continued in the area.

|

C&O A-16 4-4-2 Atlantic #290 makes for small but handsome passenger power. On the turntable at Kingston for the return north to Pratt circa 1948 Image courtesy C&O Historical Society.

|

Conveyer of the Solvay Collieries at one of the loadouts in Kingston. This company was the first to establish mining here until the Kingston-Pocahontas Coal Company assumed operations in 1923. Image West Virginia and Regional History.

|

Mine disasters were a somber fact of life in Appalachia during the early 20th century due to lax safety concerns by coal operators and the inherent risks of the labor itself. The Paint Creek watershed was not exempt from such tragedies. Tears mingled with the icy cold water of Milburn and Paint Creeks on January 26, 1929 when an explosion at the Kingston-Pocahontas Coal Company Number 5 mine killed 14 miners. The cause was believed to be from the ignition of concentrated coal dust. A total of 67 miners were in the shaft when the explosion occurred—fortunately, 53 of them escaped by another entrance located on the Coal River side of the mountain.

Overhead view of the area that once was the coal camp of Kingston. In an example of what could be classified rural renewal, the actual site of Kingston is extinct but subsequently replaced by newer mining developments of the late 1900s-early 2000s. However, a railroad no longer exists to directly serve these mining interests.

Examining aerial views of Kingston reveals that a number of structures from the original camp were extant into the 1960s with evidence of continued mining. Hoppers of coal are also visible adjacent to a tipple during the time period. Newer mines were opened in the decade of the 1980s and perhaps with this development, what remained of old Kingston was razed sans a few structures. The timeline of the active railroad here by the late 1980s is somewhat of an enigma. What the exact circumstances were that led to the abandonment of the Paint Creek line by CSX clearly involved Kingston. Whether the volume of coal here during the period declined or that CSX deemed the operation unprofitable--perhaps a combination of both--were factors. In any event, the last revenue train to Kingston was January 1988 ending a nearly a century of coal trains on the route. As an added note, one final movement on the line was reported to have occurred in 1989 with the removal of slate.

The upper Paint Creek basin witnessed new mining developments during the early 21st century that offered a menu of contrasting palettes. CSX, quick with the trigger to remove railroad during its first decade of existence, missed (or disregarded) the opportunities for it had scrapped the former C&O Paint Creek route during the 1990s. By the same token, it did not rebuild the line to serve new developments as it had with a substantial amount of investment on the former C&O line at neighboring Cabin Creek. Additionally, railroad was reconstructed on the former Kanawha, Glen Jean and Eastern Railroad (ex-C&O) operated by R. J. Corman (CSX lease) to reach a new loadout at Pax built by the Pioneer Fuel and Foundation Coal--operators of the Kingston mines-- in 2004. In essence, this enabled mined coal at Kingston to be trucked to Pax and moved by rail from there to CSX at Thurmond via the ex-C&O Loup Creek Branch. These developments deemed the reconstruction of the ex-C&O Paint Creek line moot. Curiously, a connection with the Norfolk Southern at Pax (NS) was proposed but not built.

Modeling the C&O Paint Creek Line-Black Diamonds in the Rough

There is an inherent charisma associated with modeling a setting based in the Appalachian coalfields. Ironic in the sense that it was an arduous life for those who lived it but, perhaps, that toil in a fictitious world distantly removed from those realities enhances the appeal. To say it has been a popular theme would be an understatement. Many prominent model railroads have been constructed and featured in books, periodicals, and video replicating different eras throughout the 20th century—each encapsulating elements from the respective period.

A modeler with an interest to capture the atmosphere of the coalfields on a small yet accurate scale can look to the C&O Paint Creek branch for inspiration. As the prototype extended for a relatively short 21 miles in its entirety, a number of its characteristic elements can be modeled verbatim. For starters, a condensed Handley yard could serve as the staging terminal for both loaded and empty hoppers and depending on space and/or desire, additional facilities incorporated. The section of C&O main line from Handley to Pratt can be utilized and perhaps included with a type of loop to operate inbound and outbound coal trains to the yard.

Assuming the modeler is striving for accuracy the earlier the era, the greater number of active mining camps. The pre-1932 flood era would be optimal in that regard. Coal camps such as Glenhuddy and Greencastle, for example, could be represented with a single small mine, a spur or two, and a few company homes scattered thereabout. The crown jewel must- haves for a Paint Creek layout would unquestionably be Burnwell and Kingston with passing sidings for locations such as Standard, Hickory Camp, and Coalfield. For a real--but dark--- snapshot in history and conversation piece, a layout set during the 1912-1913 Mine War period with the tent colonies and Bull Moose Special would be strikingly unique.

If beautiful scenery is an influence in selecting a prototype to model, the C&O Paint Creek line will not disappoint. Mountains are aplenty in addition to a multitude of hardwood trees to populate them with. A layout set in the autumn season would be one of colorful splendor and, of course, there is Paint Creek itself with a number of small tributaries. Without question, the scenic highlight of the setting would be a replication of the Milburn-Westerly region to some degree. For an additional challenge, the West Virginia Turnpike—either as two or four lane—could be incorporated for a mid-1950s onward theme.

The C&O had an ample variety of steam power to choose from but truer to prototype in regards to the Paint Creek branch would be the 2-8-0 in early years extending to the H-6 2-6-6-2 during the twilight era. Undoubtedly, other classes of steam locomotives were also used as needed throughout the years pertaining to coal traffic. Passenger power would also include a 2-8-0 Consolidation as well as an A-16 4-4-2 Atlantic ably sufficing in the role. One or two coaches would handle the patronage in a time setting in the pre-World War II years. A diesel era period of EMD GP7/GP9 series locomotives provide the power although others certainly saw action on the line when needed. This motive power is consistent with both the C&O and later Chessie System eras. Rolling stock is obviously hoppers but a few boxcars, gondolas, and flatcars could add some variety for occasional other needs on the route. Additional possibilities exist beyond the historical record. The railroad remained active into the CSX era---albeit brief--but a freelancer could extend its life span to a present day CSX. Another option is the independent operator---perhaps a Watco or R.J. Corman owned Paint Creek Railroad that interchanges with CSX at Pratt.

Credits

C&O Historical Society

coalcampusa.com

Kathy Cummings

Scott M. Greathouse

Art Hoffman

"Kanawha County Images-A Bicentennial History 1788-1988" Cohen/Andre-Pictorial Histories Publishing Co.

Kanawha County Public Library

"Morris Family History"

"1912-West Virginia Coal Fields"

"Speech to Striking Miners 1912"-Mother Jones

West Virginia Geological Surveys

West Virginia and Regional History

Images from C&O Historical Society used by permission. To find out more about the C&OHS go to web site: cohs.org and for sales of C&O items go to chessieshop.com.

A special note of gratitude to Tom Dixon, Jr. and the C&O Historical Society for their assistance with this project of which it otherwise would not have been possible.